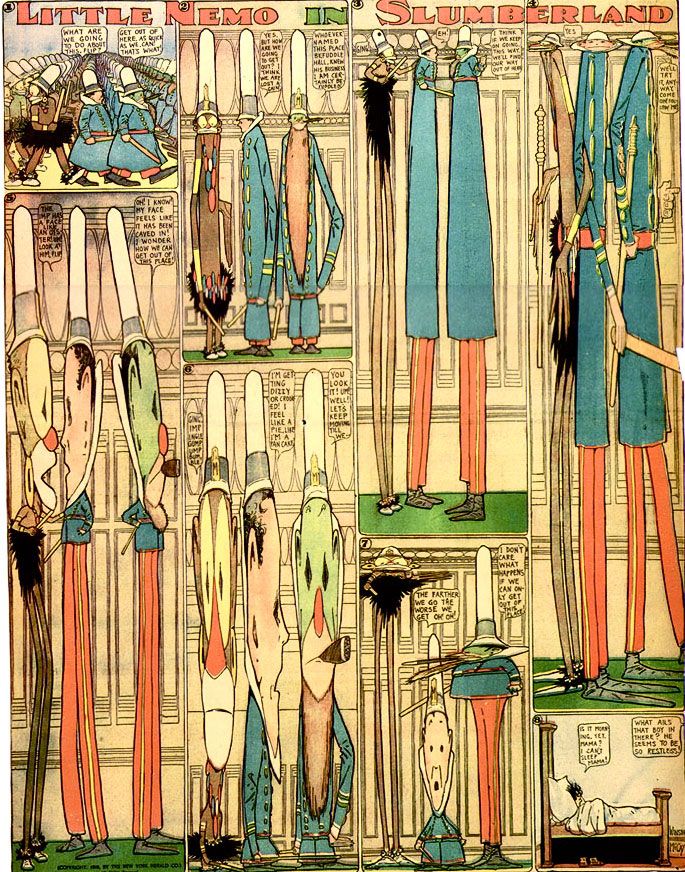

Little Nemo in Slumberland, February 2nd 1908. By Winsor McCay.

Comics and animation have an interesting relationship. Both can be broadly designated "pictures that move", both have the same typical end goal of visual storytelling, and both rely on frame after frame of closely considered progression to push themselves forward. Someone smart (I can't remember who right now, apologies) once said that animation is comics at 24 frames a second, which is basically true, especially when the physical medium -- film strips -- that animation resides on is considered. A stretch of animation celluloid is a comic, maybe a weird, incredibly slow-moving one, but a comic nonetheless. A litany of great comics artists, from Alex Toth and Jack Kirby to Matt Groening and Ben Jones, have done serious time in animation. The skill set isn't the exact same thing by any means, but there's plenty that translates.

Probably the artist whose works blur the boundary between comics and animation most severely is Winsor McCay. An early virtuoso in both media, McCay came closest to a fusion of the two with the page above, which finds its animated parallel in this video. The strange, funhouse-mirror distortions of anatomy are the same on the screen and on the page; by 1908 McCay possessed such an intimate knowledge of the character-forms he'd been drawing for years on end that he could stretch them out and squash them down perfectly, elongating and impacting their lines and contours without ever betraying the fundamental shapes behind them. It's interesting to note the difference between the printed and projected versions of this scene. On screen, the focus is on the continuous transmutation from form to form to form, the flowing and ebbing of lines that never disappear, the characters' interaction with the fixed borders of the frame. On the page, it's all about the remarkable difference between fixed forms, the way the lines change disappear and reappear in immensely different form between panels without changing what they depict in the slightest.

Those differences must have seemed pretty arbitrary to McCay as he drew the two works, though. After all, to animate the scene he drew he had to see the motion happening between the frames, to understand the exactitudes of space and shape and change going on from one picture to the next in order to make the printed version, and see the broader, more general progressions of movement involved to create the animation. 1908 was early indeed in the history of both mediums; looking at this Little Nemo page and then watching the short feels like experiencing something that could have been but never was: animation considered as another, slightly different kind of comics or vice versa, the membranes separating the media so thin that they could reach out and almost touch each other. Of course, as time went on the two forms developed vastly different languages. But for that one brief moment!

Still, we have what we have, and given that comics and animation as they are and have been for quite some time now operate in vastly different ways, seeing what's basically the same piece in both media allows an excellent opportunity to consider the formal differences that separate the two. You'll notice I haven't used the word "sequence" to refer to McCay's animation (had to stop myself a couple times but whatever). That's because it isn't a sequence, at least not in the comics-centric way we've been defining the word in this column. Though animation as seen in its raw, film-stripped form is plainly comics, it's tough to make the same claim for it in its intended state, moving images on a screen. Comics are still, static images that progress from one to the next to create the illusion of motion, continuity, time passing. That sequencing of multiple images is what makes comics comics. In animation, however, the motion is actual, perceptible within a single frame, more "real" than anything comics can achieve. And that's where the big difference comes from: because it can actually move, animation is pinned to one space, a constant progression inside the single box shape of the screen. Whereas comics move from panel to panel, box to box, which means that the action can happen within any shape of any size.

The traditional mode of "animation" in comics since McCay (from Jim Steranko on down) has been frustratingly tied to the look of the medium on the screen, moving figures around in a string of same-sized boxes that seem designed only as containers, not shapes in their own right. McCay, however, seems to have an instinctive understanding of comics' potential for feats of animation, and as Little Nemo and friends change size and shape, so too do the panels they inhabit, stretching like taffy to maintain a consistent framing of the figures' wild changes in height. Look at the layout, panel contents aside: it's animation just as much as the actual pictures are, the panel shapes and sizes artranged into a precise tracking of movement. This is what comics can achieve that film can't, a wildly variable space for presentation used to maximum effect. It's striking, shocking, the medium itself flowing and dislocating along with the characters. McCay created comics so much like animation and animation so much like comics that it may be tough at first glance to tell the difference, but he was keenly aware of the unique potentials each carried. Perhaps it was inevitable that they'd become such vastly different things, perhaps not; but looking at the prehistoric branch of lineage where one splits from another is a vital lesson in how both can be best used.