From Hell #7 (1995), page 12. Eddie Campbell.

One of the most consistently interesting aspects of Eddie Campbell's comics art -- whether it's drawn in paint or ink, with pens or brushes, in color or black and white or hazed in screen tones -- is the push and pull between chaos and control it always carries. Campbell sticks to the grid as much as anyone. His stories progress in an almost uniformly metronomic, evenly measured, deliberate fashion, more concerned with catching clear pictures of as many moments as possible and letting readers come upon the important ones naturally than thrusting anything into the audience's face. But there is always a strong element of wildness present in Campbell too. No matter the tools or the approach he's using, there are always lines or brush strokes or tone dots that wriggle away from whatever figurative content his panels hold and out toward the edges, seeking the place in the frame where they can best exist as nothing but media on paper, set free from the picture's meaning in search of their own. It's the way these two truths of Campbell's work interact, now in harmony, now struggling for control, that brings the comics to beating, vibrant life.

Few Campbell comics are more controlled than his legendary collaboration with Alan Moore, From Hell. Moore, widely known as one of comics' most exacting scriptwriters, boxes Campbell in tightly over the book's 500-plus pages: though the scratchy marks seethe wildly within the panels, the grid remains as fixed as a windowpane throughout, leaving each frame to boil with a life lightly separate from what surrounds it. It makes sense, then, that when Campbell is allowed to go wild within the book's confines, he produces some of his career's most striking work, careening from the strict formality that characterizes the Victorian period piece into the white-hot image making of the visionary.

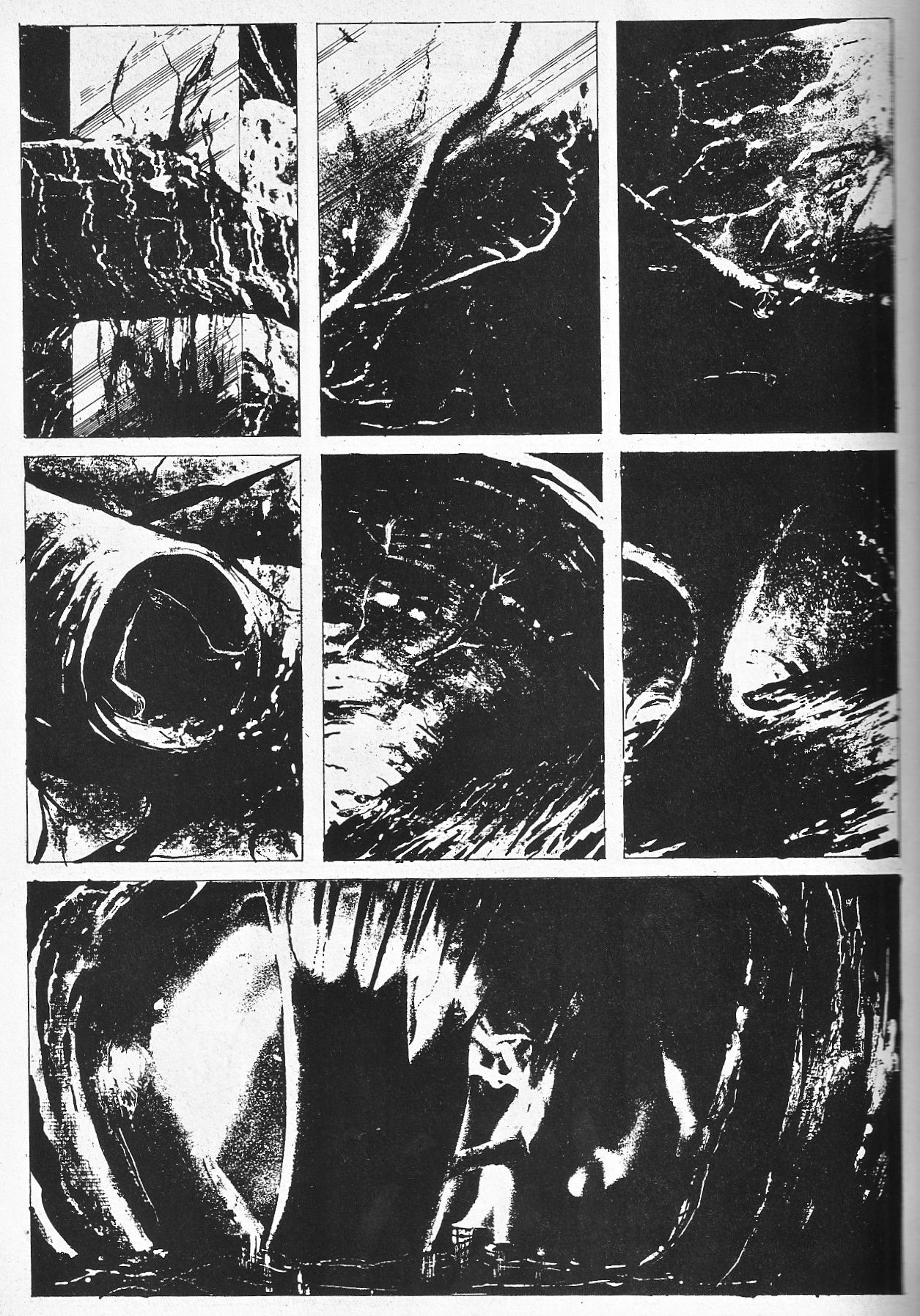

The sequence above is probably the most savagely avant-garde page of From Hell; certainly the only one that demands an explanation of its basic content when viewed by itself. Well, if I must. What we're looking at is an extreme close-up of a knife blade planing through human flesh, specifically the stomach cavity. To spread a single act -- one cut, one gesture -- out over seven panels requires a precision and flare for choreography that's simply beyond most cartoonists' grasp, but Campbell pulls it off with a flourish. In the first panel, we see the shiny surface of the blade planing through a membrane, placed right in the middle so as to neatly bisect the panel itself into equal pieces. The next shot is filled entirely with the metal's glare, a spray of black fluid rising up from the bottom to bathe it. Panel three focuses in of the spray itself as the knife passes out of sight. The second tier zooms us into the tunnel of an opened vein, and finally we arrive inside, feet panted on the floors of the body's passageways.

Making such queasy subject matter so visually appealing is no easy task, and making it appear elegant is even more difficult. But this page is an incredibly beautiful bit of near-abstract art , taking readers from the splashing, dirty-lined visual chaos of the top three panels into the sublimely peaceful, hauntingly still and silent chapel of the final frame, a world somehow both recognizable and completely alien. In context, it's a test of even the most experienced comics reader's comprehension; taken as a single page, separated out from story and meaning, it's simply seven beautiful pictures, each image both arresting and dynamic, moving you on to the next, until the full stop of the devastating last shot. Campbell's in-panel compositions ensure that this page works as comics, with lines and black spaces leading the eye neatly from one picture into the next, but the whole time the reader is assaulted with gorgeous imagery that demands a second to be drunk in fully.

It's in that deep analysis of these pictures that perhaps the most impressive thing about this page emerges: unlike just about every other comics sequence out there, Campbell's page gives absolutely no clue as to its manufacture. Are the ragged lines edging the veins dip pen? Are the splatters ink blots, or dry brush, or wite-out? Are we looking at photos, and if so, how adulterated are they? The same flat, basic black-and-white printing that allows Campbell to treat slashed-open innards with such elegance of effect ensures that these images remain mysterious, communicating nothing concrete about their origin. They're there to be looked at, not questioned; accepted, not analyzed. Campbell forces even the most curious reader into passive reception of his pictures here, and in the process reminds us why we come to comics in the first place. It's to see things we haven't before.