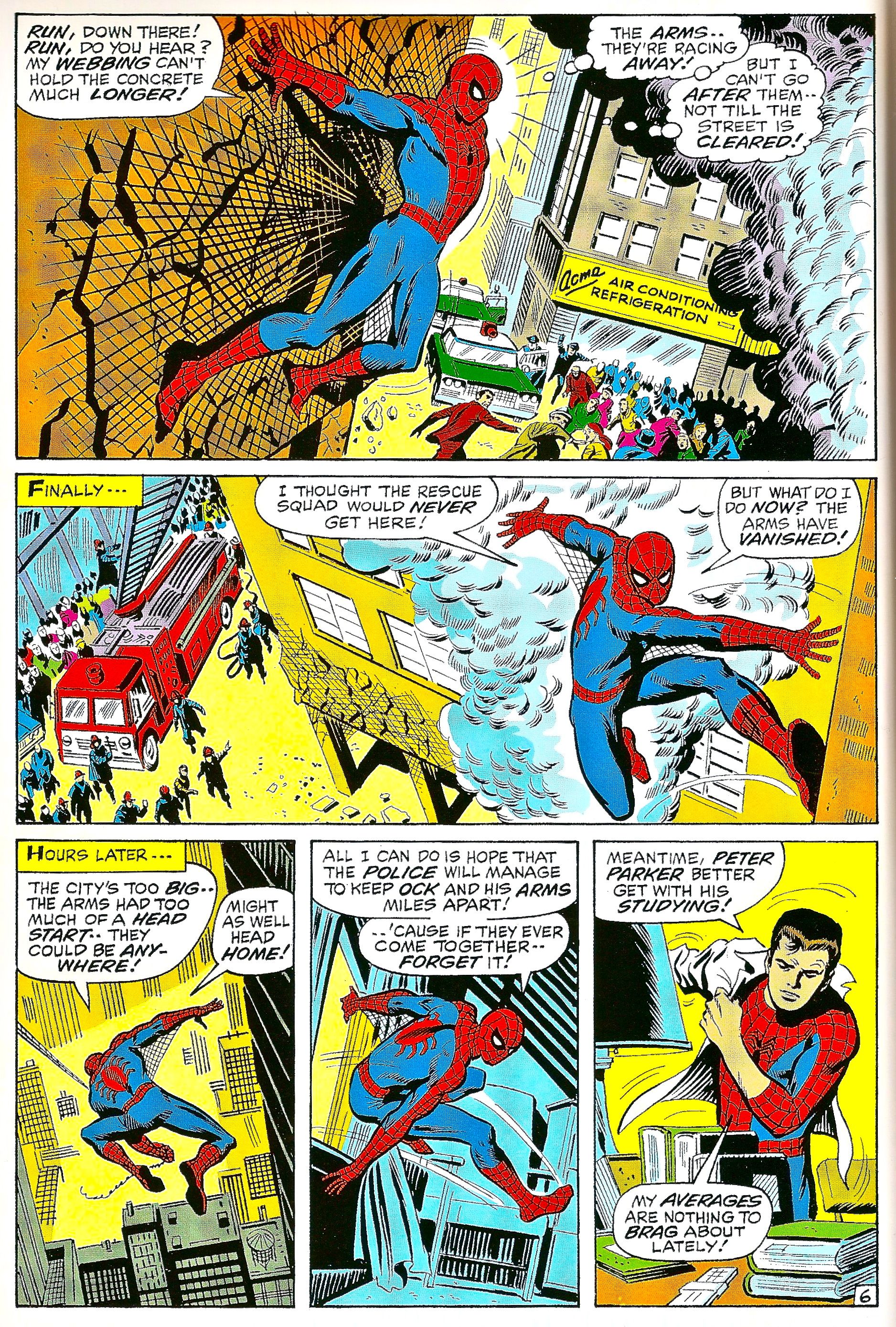

The Amazing Spiderman #88 (1970), page 6. John Romita.

John Romita came to his decades-long tenure on Marvel superhero comics from a career as a solid-to-outstanding illustrator of romance stories, and when he arrived he was asked to pencil his first costumed-action book over rough layouts by Marvel's main stylistic voice at the time, Jack Kirby. He learned his lessons from the King well. Decades after Kirby had ceased to be the company's prime mover, young artists recruited by Marvel were still sent to learn their fundamentals from Romita.

During Marvel Comics' greatest period of mainstream commercial success, it was the Romita style -- muscular but glossy, dynamic but smooth -- that gave the publisher its visual identity. If Kirby provided Marvel with its Big Bang, Romita was the universe's rapid expansion, his art bringing the heroes it delineated from comics out onto cereal boxes and binder covers and the near-ubiquitous Underoos. But though his licensing art certainly touched more eyes, Romita was a consummate cartoonist. The anecdote about Kirby breaking him in to the Marvel style is more than a charming story: it gets at what was so special about Romita's work, and why it was so essential to the development of superhero comics.

Before Romita, Marvel was Kirby and Ditko and perhaps Steranko, explosive force and mind-bending optics, pure imagination channeled panel by panel. Romita took the basics -- Kirby kineticism, Ditko atmospherics -- and grounded them in a style of staging and action blocking imported direct from his work in romance comics, flowing and approachable. More than the work of any writer, the combination of flash and humanism and pure readability in Romita's art is the foundation stone that the soap opera-styled superhero comics of the '70s and onward built upon. The page above is Romita doing what he did best, setting furious, unceasing action in the midst of a fully realized workaday world.

The approach employed here is perhaps closest to that of Milt Caniff, who backgrounded cartoon figures with realist landscapes: here Romita pops his hero out from a smooth background of midcentury advertising art-styled drawing with coiled-spring poses taken from the best of Ditko. Even against the riotous, polychromatic backgrounds of Silver Age comics, the hero screams off the page like an air-raid siren. This is comics storytelling at its most basic and effective: the most important figure on the page should be the biggest, everything should be in motion, the figures' gestures should lead the eye across the space between the panels. Every picture of Spiderman here is supported by the background, enhanced by the environmental drawing it inhabits. In panel one, the cracked masonry and hatchmarks of webbing zero in on the main figure, pulling the eye to it while emphasizing its struggle. Panel two takes all distraction away from the figure as it leaps free against abstracted, undemanding puffs of smoke. Panel three frames the figure with detailed architectural drawings but simplifies them more and more the closer they get to the figure. Panel four clarifies the motion's direction with the shadows of the blinds on the back wall. And after three frames that read almost as the stages of a single gesture, panel five brings us out of the world of the superheroic and back to reality by foregrounding mundane objects, obscuring the hero with the demands of his life.

Also notable here is another reason Romita was so important to Marvel's commercial success. This page carries as much evidence of writer Stan Lee's tendency toward over-elocution as any other example of prime-era Marvel, but where Lee's verbiage feels intrusive over Kirby and Ditko drawings, Romita was able to work around it. The main figure folds up double beneath the heavy balloon of panel four, enhancing the drawing's action while allowing the reader to plow through Lee's heavy dialogue unimpeded. In panel three the tiny figure emphasizes the vastness of the city wile also leaving plenty of open space for the words. Romita's every frame allows Lee to fit multiple balloons into it without upsetting what he's doing. It isn't the visionary splendor of Kirby or Ditko: it's popular entertainment trying to function at the highest level of craft that it can. Judged by this standard, Romita was and remains the quintessential Marvel artist.