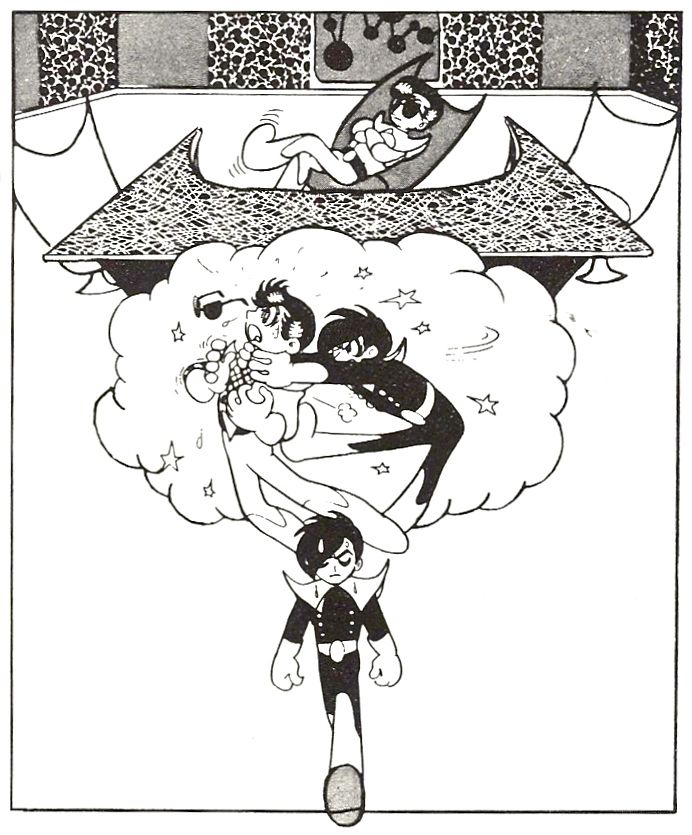

Phoenix: Future (1967), page 15 panel 9 (or is it panels 9-11?). Osamu Tezuka.

The easiest way of thinking about sequence goes something like this: multiple panels, related by subject or context and taken together at a steady rate, fuse together into a single, more communicative thing. Something that imparts more meaning than a single drawing can. But it gets a little more complex than that when the question of what exactly constitutes a panel is raised.

One might say it is an individual drawing, and be correct in a high percentage of cases. But the true difference between "panel" and "sequence" is functionally impossible to pin down, better defined case by case than with a single sweeping bit of language. After all, it's no easy task to define what an "individual drawing" is either. Is it one fully formed object, such as a figure or an environmental feature? Perhaps not -- there can be plenty of those in single panels. Is it everything an artist puts down into one uninterrupted space? Maybe, but in that case are word balloons separate panels? The lines blur when you look at it too carefully, and as with everything in the language of comics, an attempt to state a definition with words is doomed to fail. The eyes know better than the written word can say; better to go through a book of your choosing, any will do, and let them tell you that this thing, this drawing or collection of drawings is a panel, and this one a sequence.

Sometimes, however, even the eyes can be stumped. This Osamu Tezuka image is a piece of comics that takes up the space between panel and sequence, easy enough to claim as both but impossible to really give a single defining word for. Its status as a single panel rests on the box it's bordered in, four lines encompassing everything, encouraging the reader to view what's inside them as a single unit. But Tezuka seems to want us to question the sanctity of the panel border here. Look at the bottom line of the box, where a foot steps ever so slightly out into the beyond, the sole of its shoe almost providing a through-line for the border to continue along; almost, but not quite. Here, Tezuka is saying, a panel isn't as easy as "what the box holds".

So it's only fair to take a look at what's in the box as sequence. There are other reasons the picture above works as a progression, rather than a snapshot of a single moment. Though there is no actual elapsed story time running through it, it still gives the multiple views into one thing that sequence does. The man at the desk in the top of the panel is cut off by the thought balloon in the middle, which in turn cuts off the figure striding away on the bottom. The way the balloon completely separates the two gives it much of the individual panel: it is another moment, another subject (completely imaginary though it may be), inserted between the two subjects of the larger picture. It separates them in space, forcing the viewer to read through the image instead of taking it as a whole.

That's sequence, pure and simple. Tezuka's use of it here is masterful, breaking up a single moment with the kind of simultaneous inner and outer view of a character that's usually only seen in prose literature. It's a beautiful use of the form, running thought alongside the physical with an assured grace and perfect readability. Whatever one chooses to call it, panel or sequence, this is comics functioning at the highest levels.