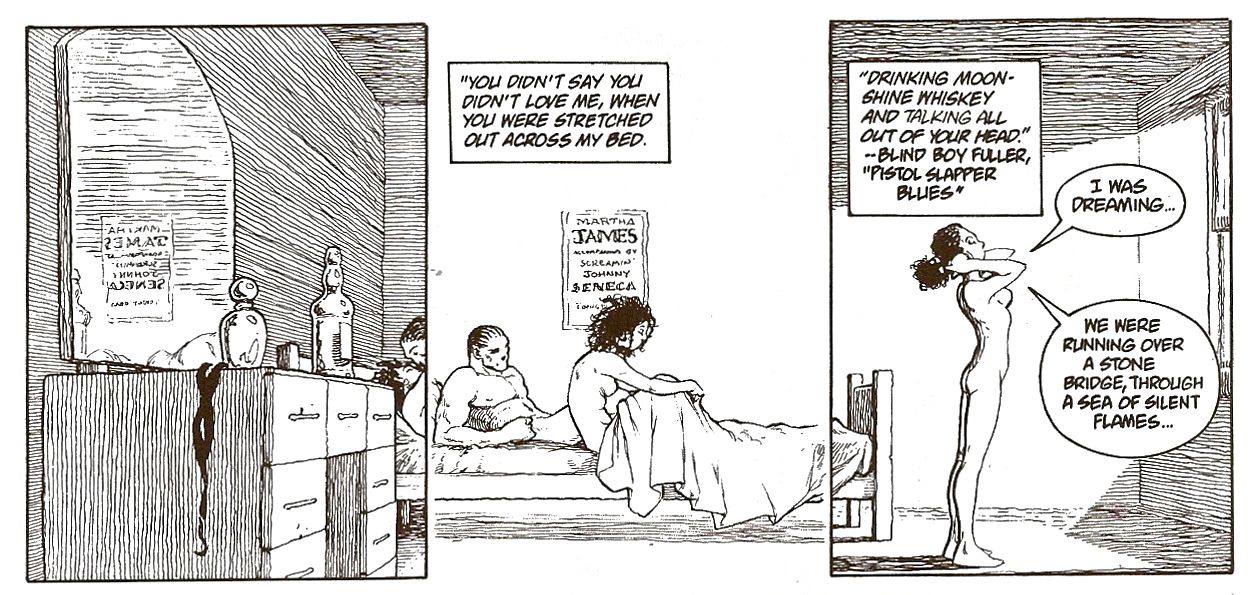

"Blackheart" part 2 in Dark Horse Presents #92 (1995), page 1 panels 1-3. Frank Quitely.

Sequence is what puts the component parts of comics -- individual panels -- together. It's as fundamental to what the medium is as anything else. It provides comics with their high-flown academic code name, sequential art, and it's what makes this a form that we read rather than look at. But there's not much as far as a definition for "sequence" as it applies to comics art. What is it? It's nothing that looks a certain way, or even acts in a certain reliable fashion. In comics as they're most often drawn, it's not even anything that gets put on the page; the closest sequence comes to a visual identity is the blank white space between the panels. It's not a shape, it's not a size, it's not a color, not even really a single formal device or artistic conceit. It goes beyond that. It's more universal, subject to as many interpretations as there are artists who have used the medium. Sequence is what makes comics comics, and as such I'd argue that the ordering of images is the most important aspect of a comics work that anyone, whether writer or artist or both or otherwise, can contribute to.

The different forms sequencing takes -- its refusal to be pinned down as one thing or one way of things -- is what makes it so difficult to think about. One of the few common denominators between comics sequences of all kinds, however, is movement. Movement through space comes to mind first; the physical motion readers' eyes and story contents alike are subject to as panels progress across or down a page. But just as inherent to sequence, and every bit as interesting, is movement through time.

Temporal movement in comics is more difficult to think about than spatial movement because there's no hard and fast law that governs it. As sequences move through the space on the page they are always expanding, taking up more and more physical area with every new panel no matter its relative size. Movement through time is trickier, though: a sequence can progress from beginning to end in a more or less naturalistic manner, but it can also move backward via flashbacks, or present multiple views into a single, isolated instant. Or at least it can in-story, because as experienced by readers a sequence's movement through time is equally legislated, always one moment at the beginning to another, later moment at the end. As we experience it, sequence is always a chunk of time eaten up, the space between the tick of the clock when we apprehend the first panel's contents and the tick when we finish with the last.

This being the case, it falls to the artist to dictate just how the time between the panels passes. Of course, no artist can claim total responsibility for the way a reader perceives their sequences -- after all, it's up to you how quickly you read anything. The power in the artist's hands is the power of suggestion, of indicating how the in-story time is passing between each individual image, and by doing so influencing the amount of time a reader is likely to take with each frame.

There is a dominant mode of sequencing, one that takes precedence especially in American genre comics; moment to moment, action to action. Unless the space between the frames involves a change of scene, you'll rarely see it take up more than ten seconds of story time, and rarely less than one. There are reasons for this -- it's basically impossible to work the panels in any other way when there's dialogue going over them, and comics that serve as a record of characters' physical actions need to be precise and regimented in recording them -- and those reasons are what makes it so nice to see an artist of American genre comics do something different with sequencing, as Frank Quitely does in the panels above.

Quitely takes in a vast gulp of time with the gutter between panels one and two, as night becomes morning in the blink of an eye. That's nothing unusual in and of itself; as I said, scene changes happen all the time between panels, frequently taking up spaces greater than a few hours. What's interesting is that the significant shift in story time involves absolutely no shift in story space whatsoever. It's the passage of an entire night, unseen against a single background. As panel two dawns the camera remains fixed in place, unmoved. That may not sound too remarkable, but it's impressive when you think about it. Shifts in space are comics' best indicator of shifts in time -- for example, when a sequence goes from town to country or jungle to city, the reader can be fairly certain that a good while has passed to bring the action there. But in this sequence the setting gives not even the barest hint about the time that's been passing between the panels. It's all down to Quitely's drawing, specifically his ability to indicate darkness and light with his delightfully shaky, Robert Crumb-inflected hatching, that allows an instant understanding. The first panel is dark, filled with shadow: night. Then comes the blinding flash of morning, and finally the glow of sunlight through the window to make sure we understand.

It gets even subtler than that. Quitely plays with readers' perceptions of just how much time is passing between the panels by using an equally divided grid layout, a rock-steady spatial rhythm that grates up against the temporal lurch between the first two panels and the fade into the relatively small blip between the second and third. But despite the close proximity of morning's panels to night, and the use of a moment-to-moment, syncopated design, it's impossible to miss the hours that pass in the crossing of this tier. The middle panel, a shocking burst of brightness in between two more evocatively lit frames, irritates the eye (which is drawn to dark areas and shrinks from lighter ones), trapping it in the drawings' specifics to such an extent that even the most casual read-across proclaims exactly what's going on.

That, of course, is the ultimate goal of comics sequencing: the creation of picture progressions that read as seamlessly as prose on the page, put down in a universal language no alphabet can hope to touch. With this end in mind, countless artists have done countless things with their sequences, with the space and substance in between their drawings. It's not one thing. It can't be. It goes so far into the minutiae of space and time, a panel a millimeter wider, a gesture a nanosecond farther removed -- that no two are ever quite alike. And that's what makes it, and the comics it creates by its very being, so endlessly fascinating.

Next week on Your Wednesday Sequence: Guido Crepax