The name Paltrow is certainly well-associated with show business, and like his father Bruce and sister Gwyneth before him, filmmaker Jake Paltrow is carving out his own niche in the industry.

Having established himself as a director on prestige television series like NYPD Blue and Boardwalk Empire, Paltrow has segued into filmmaking, and his latest project Young Ones is rooted in a near-future, barely sci-fi world in which water for irrigation is in short supply and under rigid control.

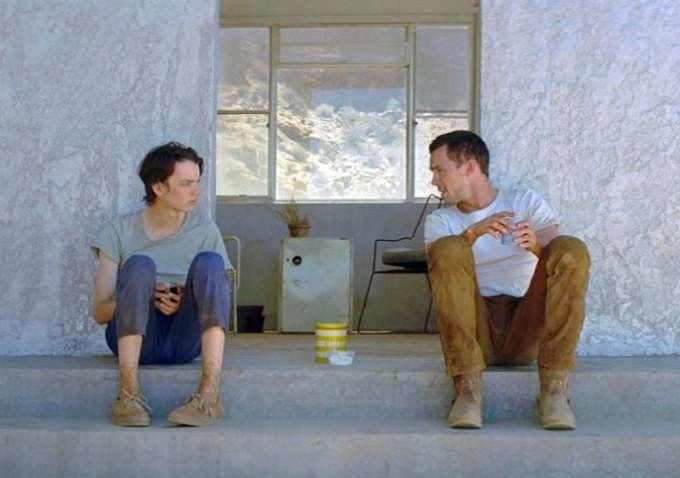

Michael Shannon stars as a morally upright but profoundly haunted farmer who struggles to provide for his family (Kodi Smit-McPhee and Elle Fanning) in a parched, inhospitable environment. With the help of his son (and a robotic pack mule, he hopes to create a desert oasis for farming, until a young neighbor (Nicholas Holt) sets his sights on his land.

In an interview with Spinoff Online, Paltrow reveals his passion for blending drama fueled by very human characters with the trappings of believable sci-fi landscapes, and how on an extremely tight budget he was able to bring the Young Ones world to life.

Spinoff Online: I’m curious where the first points of inspiration came to you – for the aesthetic, because it was unique, but it also felt like there were some more obvious overall inspirations.

Jake Paltrow: Well, as far as the aesthetics go, there was really only one movie that we looked at, or that we would even talk about, in terms of something we liked and thought maybe we could do something – or at least lens it in a similar way – and that was a movie called Silent Light, a movie about Mennonites in Mexico. It’s very good. Beyond that, we really tried to work from a pretty intuitive kind of place, Giles [Nuttgens], my cameraman, and I and the art department. I think there’s already so many unknown influences sort of in me already, as a writer and somebody who watches movies and all that, that I think in a lot of ways we try not to mine any of that stuff overtly. So we’re not watching tons and tons of movies before we go and make one of these things. There’s a process that I have with the storyboard artists when we’re doing it, but I really just try to think about the way I’d like to see it. And I feel like whatever the influences are, are probably baked in so deep, at this point, that I wouldn’t even necessarily know what they are directly. So whatever somebody would feel they may be are probably right.

The science fiction trappings really aren’t the thing that drives the movie – it’s the human relationships. What brought you to that sci-fi framework as a means to for telling this kind of human character story?

Well, I’ve always been really interested in it, in general. Most of the things I’ve worked on had a fantasy element or science fiction element. I’ve always been interested in robotics. I like burying sort of personal storytelling within genre like this, because I think it gives a certain elasticity to what you can do – that you can push the limits of reality or naturalism or something – and it allows you to work inside of a space that’s less limited. And I think for me, or what I’m interested in, I don’t want the plausibility to get in the way, of what I’m trying to tell, and at the core of these things are these human relationships – especially in this movie. So that’s the most important part of the thing, and I want that to really work. The circumstances that they’re living in, the political landscape, it’s the backdrop for the whole thing. Those are all big, big parts of the movie and inform all of the decisions that these people are making. But first and foremost, most important to me, that the core human relationships are the core of our story.

At the heart, there’s a father-and-son story being told, and I imagine that was an interesting thing for you to approach, as a filmmaker doing the very job that your own father Bruce Paltrow did.

Definitely. And there’s a lot of my father in Ernest, the Michael Shannon character. And I hadn’t written anything, really, about that or about him or about our friendship, and we were very, very close. And so I wanted to just try to capture his compassionate, tough guy qualities, which were very heroic, at least to me. And I like putting all of those in an extreme environment, and actually – as opposed to being a kid with a guy like that where you felt this person really will take care of you no matter what, into an environment where in fact he has to. Which is a movie thing. In movies we have to make these things sort of life or death, one way or another.

How do you feel your directorial or filmmaking approach is similar to your dad’s, and how do you feel that it’s very different?

That’s a good question. I don’t know. I think, toward the end of his life, the last film that he made, he was very, very sick, so he wasn’t totally himself. And I think a lot of the making of his last movie, Duets, was much more about just getting through it, as somebody who’d just been through cancer surgery, and so it was sort of like watching him survive through it. He had prepared it to a point, so he was able to stick to a sort of roadmap, but I just remember it was such a difficult shoot for him. And before that, I had never really been around him filming more than an hour or two visiting a TV set, or something, so I had never been around him as he was planning something. And he had only made one other film two decades before that one, so I didn’t really have a sense of what his process was so much as a director. I got a sense of his process as a producer and the way he managed his TV shows and the writers and his loyalty. I think he was a real taskmaster and very tough on certain people and had a reputation for being very tough with people. But I think his compassionate side outweighed that, from my memory of it at the time, and from talking to his friends about his methods. And the people that really flourished under him. You look at the people that he sort of started in the business, and it’s a very long list of very talented people, so I don’t think you get that out of just being a tyrant. But I know, in a way it’s too bad. I feel like I probably missed out on really having an understanding. I was just a certain age, where he wasn’t making something of his own. And then when he did, he was sick, so I don’t know if it’s a good enough example of how he did it.

You mentioned your interest in robotics, and I’ve heard how you kind of went to the mat to get the money to get the special effects done – especially the robotics – the way you wanted them to look, so tell me a little bit about that.

Yeah, I think in the last few years, foreground CGI has made huge strides. I always felt very sensitive to it, and it wasn’t something – So, I’d always imagined this character being a practical thing. I wanted to take a much more Stan Winston sort of approach to it, “How could we do it more as a puppet or more as somebody inside the thing?” And I had a visual effects guy come in who said, “Let me just prove it to you, this idea that you’ve had, mixing the puppets and everything.” And it was very, very convincing having it be half-puppet and half-CGI. And I realized it gives tremendous flexibility on set. And that, on a movie of this scale, is sort of everything. You can’t really slow down to be able to do motion control and all that sort of thing, and visual effects were evolved beyond that. So I knew how much money we had and knew how many shots that I wanted to accomplish. We sort of worked backwards from that, really. We had such a short schedule. The ultimate methods, the way that we did it, were really effective. And then, just the talent of the people that are doing the effects, I think is why they’re so seamless. To my eye, which I feel like is very sensitive to not-top-grade visual effects work, I think this stands shoulder to shoulder with the biggest and best companies out there.

Is this a genre territory that you want to continue to mine? And do you want to stay in that very human feel or would you like to take it to a more epic, spectacular scale?

No, I’d like to explore a story like this as probably a little bit bigger. I mean, I’m sort of working on something right now that is, so we’ll see where that falls.

Tell me about your cast. You really hit the jackpot with your four leads in particular – Michael Shannon, Nicholas Hoult, Elle Fanning and Kodi Smit-McPhee. I thought this was a revelatory Michael Shannon performance, especially. You used him in a way that he is not always used, and it was very effective. Tell me about getting those actors and getting those performances from them.

Yeah, Mike came last. The other actors had been signed on to the movie for a while. We had it going. We prepped it first in Spain, and it was stopped, not long before we were about to start shooting it. And it was reconstituted in South Africa, and then the actor that was playing it sort of fell out. And we were able to get Mike for it at the last minute, which was just the luckiest, greatest thing for the movie. And, we didn’t have a lot of rehearsal, so everybody just came with their idea – we had a time to talk on the phone before they arrived. And it’s that reminder that the best actors sort of really just bring it all with them, and there was very little to say to them, once they had shown up, to do it. Their takes on the characters and the approaches and how they wanted to play these things were – not even that they were close to how I’d imagined it was in my minds-eye, they were just right. The way that they approached it was so thought through and so good, that there wasn’t very much for me to say. And in terms of Mike, there’s something really beautiful about seeing him playing this warm, heroic person, because that’s not something we’ve seen him do a lot. And I think Mike’s a lot more like that as a father and in his own life, than he is in movies where he’s playing these very intense and emotionally compromised people, which I think he’s known for, and so it’s nice to see him in this space. I think people, hopefully, will connect with that.

Was it an easy environment to shoot in, physically?

Oh, no. No, it was really – it was the most challenging thing I’ve experienced, and it was the most challenging shoot that everybody I’d talked to on the movie had been on. These are people that have been making movies a long time. It was just the heat. And hiking up and down these mountains and carrying all that gear up. The heat adds a layer that sort of makes it – you come up against the physical tolerance of what people can achieve within a day. And so when you have a move schedule, you have to achieve X amount of shots in this amount of time. There’s like an algebraic thing to it. It’s like, “In this heat, you can walk this speed, up this slope, at this time.” So you really do come up against a reality that I wasn’t expecting. I think there’s also something inherent in filmmaking, it’s like ‘We’ll get it done.’ And it’s unusual to come up against something like that.

I imagine that looking through the lens of the camera, the bleakness of the landscape gets you halfway to that dystopian feeling you need.

Yeah, and I guess to me, I guess it is dystopian in a way, but, you know, it’s not post-apocalyptic in any way, and that’s important to me. Because it’s not some supernatural event or nuclear explosion, or something that doesn’t feel close at hand. It’s an environmental disaster that’s as naturally occurring as it is sort of manmade, and the consequences of all of that stuff and the decisions that people have made that have sort of gotten us to that moment. And really extrapolating a political landscape that’s very much based on what’s going on today. And I think that’s a real tradition inside the Spaghetti Westerns is dealing with a contemporary, political issue or issues and playing them out in a heightened, storybook context that’s more good and evil, in a way.

When you grow up with a family in the entertainment business, you tend to go one of two ways: You don’t want anything to do with it and choose to do something totally different, or you want to embrace it and walk directly into it. When did you know that becoming a filmmaker was the path you wanted to go down?

I think actually being a filmmaker came in my later teens. What I was very interested in – starting maybe at nine or ten or eleven – what I was very into were special effects. So I wanted to be like Rick Baker or Dick Smith. Sort of like a creature creator and monster makeup and that sort of stuff, but I had no aptitude for it. I couldn’t draw. I couldn’t sculpt well at all. And Dick Smith – you know, in the back of Fangoria magazine, when I was a kid, you could do this mail-away class, and I sent all these examples of my work, things I’d sculpted and rubber-latex masks and stuff, and I got this letter back from Dick Smith, or somebody at the school, saying, “You’re nowhere near ready to be part of our mail-away class, let alone the class.” And I think all that did was it got me into making these shorts that showcased the effects – the decapitated head and all those sorts of things, and that was the beginning of it. Then I had a teacher in high school that introduced me to a whole different kind of movies, and that I think was when the hook was really set, much later on.

Given that you grew up around people who do this for a living, who did you meet along the way that really inspired you – someone that you got a personal encounter with that was able to help you stay the course in what you wanted to do?

Well, Gwyneth made a movie with Paul [Thomas] Anderson – her first movie, Hard Eight – and meeting him, when he was sort of meeting her for that movie, and then we became friends and he really helped me with my first short film, sort of getting that all finished. And I worked on Hard Eight, which at the time was called Sydney, and he was just a very generous guy in general with his time and knowledge and stuff. And he was very young at the time, too, I was 19 and he was probably in his mid-20s. And I made my first short film, and he was very helpful with finishing it. He was sort of the gold standard of somebody who was getting unusual work made, and obviously he’s consistently done that.

Young Ones is playing in select theaters and On Demand.