by Robert Jones, Jr.

I. Love Is the Message

Wonder Woman is love, baby; all love and nothing but love, so help her Aphrodite. Or so Geoff Johns insists. Then again, Johns approaches Wonder Woman from a perspective not all “Wonder Woman” readers can appreciate. In his stories, she is the usually the one hero guaranteed to be aimless, nonplussed, diffident, undiscerning, and yet sanctimonious. For this reason, “Wonder Woman” readers were alarmed when they learned that she would play a significant role in DC’s latest big event miniseries, “Blackest Night,” penned by Johns; and they were apprehensive when the spin-off miniseries, “Blackest Night: Wonder Woman,” was announced.

“Blackest Night” is actually a “Green Lantern” storyline. The plot revolves around the idea that every color in the rainbow represents a different emotional power that can be harnessed and channeled through a power ring much like the one worn by the Green Lantern. Black (not really a color) represents evil and death (*eye roll*) and it is up to the other colors (red/rage, orange/avarice, yellow/fear, green/will, blue/hope, indigo/compassion, and violet/love) to join forces and defeat the zombie agents of death, the Black Lanterns. Despite its preschool-esque, Crayola-wars premise, the series does manage to entertain; and the fact that the brilliant Ivan Reis deftly handles the art chores does not hurt one bit.

Wonder Woman did not play a huge role in the series until issues #5 and 6, when well-known DC characters were deputized as Lanterns and given ring assignments based on how closely they embodied each emotion. Green Lantern kept his green ring, of course; the Flash got a blue ring; and the Atom got an indigo one. In a previous interview, Johns indicated that the remaining ring colors represented the more extreme and irrational emotions on the spectrum. The recipients of those rings included: Mera (red), the Scarecrow (yellow), Lex Luthor (orange), and Wonder Woman (violet).

As an aside, not a single man possesses a violet ring. Johns explained that while anyone could join the violet corps, most men were unworthy. (Really? Most men? What about Superman?) That sounds like chivalrous reasoning, but it is actually specious. How could it be that most men in the DC Universe are incapable of representing love? Is that not a defect? Does that not say something very unnerving about the men who populate this fictional place? Could Johns really be that cynical? Or did he simply find a delicate, self-effacing, and completely disingenuous way to say, “Ain’t no way we’re putting one of our guys in some revealing, sissy, pink outfit! So it’s gotta be a girl. And what girl embodies love better than the most beautiful girl in the world?” Does Wonder Woman fit the bill? Whether or not she does, Johns made her a member of the all-female violet corps. It is not as bad as it seems considering the color Johns could have assigned her (yellow might have been more apropos given what some creators and readers actually feel about her).

As questionable as his approach to Wonder Woman may seem to admirers of the character, Johns’s widespread, mainstream appeal is no mystery. He has a great deal in common with the majority of his following, including a penchant for spoon-fed exposition, an almost pathological reverence for a peculiar type of alpha-male hero, and a desire to boil every character down to a one-sentence, or, as with “Blackest Night,” a one-word description. (Perhaps this explains his approach to Wonder Woman, and why that approach is so at odds with her fans’ vision: In many ways, Wonder Woman is a character that defies simplification.) Add to this a knack for returning characters to forms most recognizable to the thirty- and forty-something-year-olds who are currently the majority of comic readers and collectors. In plain terms, Johns’s success can be attributed to the notion that what he writes is essentially fan-fiction. His readers feel, on some level, that if they had the opportunity to write comics, they would write them just like Geoff Johns does. Perhaps that’s not a bad thing, but it’s certainly not a good thing, either—unless “good” is defined in commercial terms rather than artistic ones.

Whatever incompatibility exists between Johns’s writing style and Wonder Woman’s character, Johns did give some “Wonder Woman” readers a gift: He announced, after much speculation, that critically acclaimed, former, and controversial “Wonder Woman” writer Greg Rucka would be writing “Blackest Night: Wonder Woman.” The gesture suggests that there are really no hard feelings between Johns and the Amazon Princess; just a profound misunderstanding.

II. Where Is the Love?

Greg Rucka is undaunted. He wrote “Wonder Woman” with great imagination, wit, seriousness, and aplomb. Legend has it that he was set to explore Wonder Woman’s bisexuality during his run before DC’s parent company, Time-Warner, nixed the idea. It was he who wrote the story in which Wonder Woman was forced to kill Maxwell Lord in order to save Superman and the world; a story that changed (some say damaged) Wonder Woman forever. Rucka was removed from the book just before it was rebooted. He never had the opportunity to explore the consequences of Wonder Woman’s actions—that is, until Geoff Johns asked him to write the “Blackest Night” tie-in.

“Blackest Night: Wonder Woman” serves two purposes: First, it fleshes out ideas, situations, and scenarios that could not be fully explored in Johns’s main miniseries; and second, it allows Rucka to, in some small way, revisit points that he might have left unfinished from his previous run. Both are very tight restraints to place on a three-issue series. The former requires Rucka to stretch scenes that literally last one panel in the main book to twenty-two pages and still keep things interesting. The latter challenges him to make the point without being didactic. Additionally, he must work with the limitation imposed upon Wonder Woman by Johns: She is love—period, the end; make it work like Tim Gunn. Given the parameters, Rucka works wonders. He writes the Amazon Princess with such ease and expertise that it is not only as if he never left, but it is as if he never stopped thinking about her.

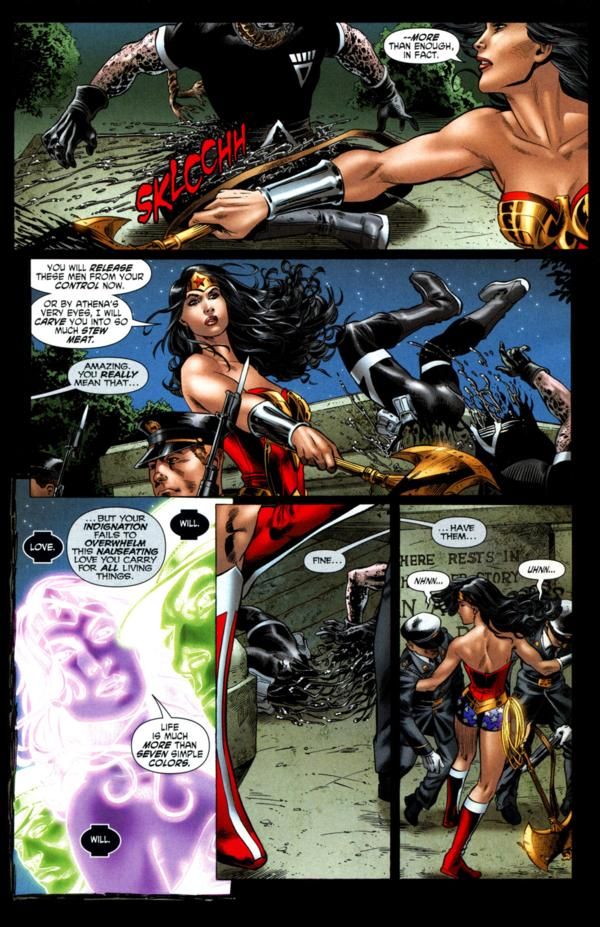

The three issues work as a trio of vignettes: 1. Wonder Woman must once again do battle with Maxwell Lord, who has risen from the dead thanks to the power of the Black Lanterns; 2. Wonder Woman must free herself from Black Lantern control before she kills Mera; 3. Wonder Woman understands herself as love and helps to heal Mera. Even in this context, Rucka does not shy away from controversy: The first battle takes place at Arlington National Cemetery and Wonder Woman must fight the reanimated soldiers. Rucka also does his best to distance Wonder Woman from the sillier aspects of the “Blackest Night” premise. “Life is much more,” she says to Lord, “than seven simple colors.”

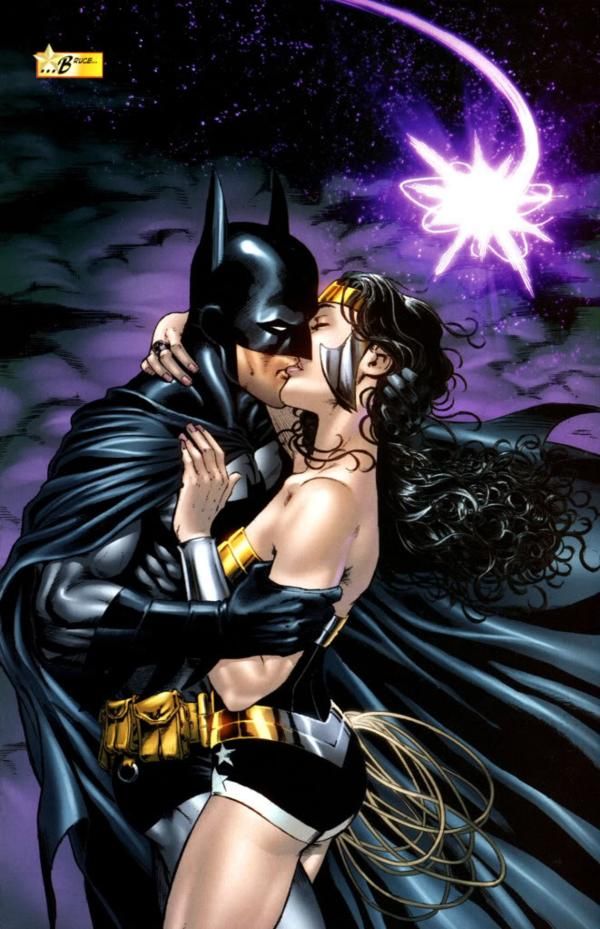

However, there is one aspect of “Blackest Night: Wonder Woman” that rings incredibly false. According to the series, Wonder Woman is secretly, quietly in love with the Batman. It is this love—not the love she has for her mother or her sisters—that frees her from the black ring’s influence. It ties back to an idea in the main miniseries that suggests Batman is the emotional tether for all of the DC heroes. Okay, understandable. Nevertheless, the revelation is still odd because this love has not ever made itself apparent. There had been some flirting, a stolen kiss or two, but never any indication whatsoever of a deep, abiding love between them. It is even weirder when her romance with Tom Tresser in her own book is taken into consideration.

If ever there was a situation where characters were forced to service a plot, this is it. The scene is clunky, inorganic, and strained. Admittedly, it is better to have Wonder Woman’s sexuality explored than ignored completely. But this is the expressed danger of the oversimplification of “Wonder Woman is love” as Johns has imagined it: Suddenly, she becomes the long-suffering Damsel of Furtive Sighs who yearns for the love of someone who is at once unavailable and incapable of returning it. Only someone who did not understand Wonder Woman in the least could believe such an arrangement to be natural. Only eyes that perceive love as irrational could observe that scenario and suppose it to be true. Turn, O William Moulton Marston, creator of Wonder Woman; in your grave, turn.

At least Rucka proves that he has a grasp for Marston’s Wonder Woman texts better than just about everyone else. The common perception is that Marston was a pervert who was into sadomasochism and bondage and Wonder Woman was simply a product of his perversion. To what degree that is accurate is subject to debate, but what is clear to anyone who can move beyond the surface is that what lies beneath is commentary about freedom, sexual and otherwise. Rucka dug deep. Maxwell Lord says to Wonder Woman, “I think I know the answer to this question given what you normally wear, but are you into bondage?” “No,” Wonder Woman replies. “Liberation.” Precisely, Greg. Precisely. So there should be no pining away after dead billionaire playboys; for what is that if not bondage?

III. Redefining the Message

Other than the Batman gaffe, Wonder Woman is confident and effective in this tie-in, which is a wildly unpopular way to portray her. Because Wonder Woman has a reputation for being too perfect, there is a strong desire to knock her down a peg or two. This speaks to a larger phenomenon in the industry. Many of today’s comic book producers and readers have very specific demands of their “superheroes.” Rather than aspire to heights set by hopeful, “perfect” characters like Wonder Woman (and Superman, for that matter), many would prefer a hero of lower standards. Some desire a character that more closely reflects their own failings, fears, and flaws, not a character that merely overcomes obstacles and triumphs in the end. In other words, superheroes who are not super at all, but are Average Joes and Janes (not too average a Jane, though; she must be buxom enough to make even circus freaks raise an eyebrow). It is all quite unimaginative; and the glut of books about psychotic orphans with rodent fetishes, cigar-smoking serial killers in superhero drag, and alien women with breasts the size of Legion Time-Bubbles cluttering the stands makes that all too apparent.

Looking at the stunning artwork in “Blackest Night: Wonder Woman” makes it hard as hell to be so critical. As exciting as it is to have Rucka writing Wonder Woman again, if just briefly, the true draw is the artist, Nicola Scott. Quite frankly, Scott illustrates with a sensibility not seen very often in mainstream comics. There is something very pristine and feminine about the line work, something very considered in the panel placement and splash pages, something very sophisticated about the action. Aesthetically, her designs evoke both the darkness and whimsy of the best childhood fairytales. In short, her work is genius and her rendition of Wonder Woman should be the model for every artist who illustrates the character. Scott’s Diana is stunning in every conceivable way, from her luscious, curly hair, to her gleaming tiara. If there is any real love in this series at all, it is in Scott’s work.

Nevertheless, the “Wonder Woman as Love” paradigm continues to grate. That is, unless it is placed in a context that makes her larger, freer, better respected. Here is one suggestion: Often, Superman is invoked as DC’s resident Christ figure. It is a designation that demands veneration and Superman has held the title ably all these years. However, with Johns’s insistence that Wonder Woman is the DC answer to love, a strong case can be made that the Christ title, and the accompanying reverence, rightfully belongs to her. Think about it: Jesus’ birth was immaculate and so was Wonder Woman’s; Jesus has divine heritage and so does Wonder Woman; Jesus was sent forth to save the world from itself and so was Wonder Woman; Jesus was a rabble-rouser that challenged patriarchal institutions and so is Wonder Woman; Jesus had long, gorgeous, flowing hair and (thanks to Nicola Scott) so does Wonder Woman; Jesus was resurrected from the dead and so was Wonder Woman; Jesus ascended to the heavens and so did Wonder Woman; Jesus is love (at least, according to some Christians) and now, thanks to Johns, so is Wonder Woman.

For Athena so loved the world, she gave her only begotten daughter and all that….