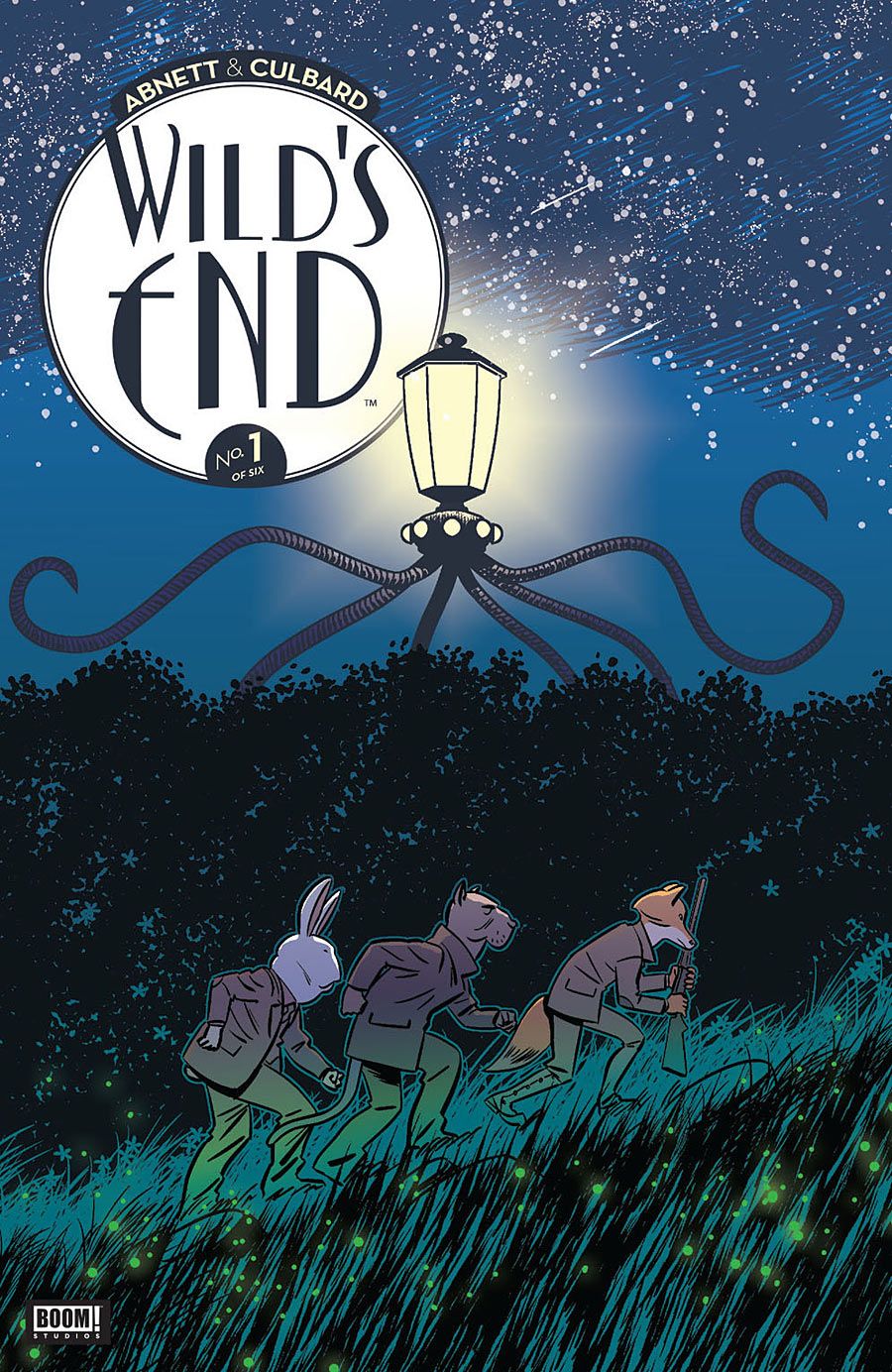

"Wild's End" #1 by Dan Abnett and I.N.J. Culbard has been described as "The War of the Worlds" meets "Winnie-The-Pooh." The first issue introduces the world of Crowchurch, a sleepy village where it feels like nothing bad can happen. The tone is similar to Neil Gaiman's "Stardust," too, but the closest analogue is Kenneth Grahame's classic book, "The Wind in the Willows," in which all the anthropomorphic animals are adults, sometimes with adult problems and failings.

Abnett and Culbard introduce the main characters quickly and gracefully. They are all common types. There's the newcomer, Clive Slipaway, a quiet, ex-Navy man whose reticence seems to hint that he'd rather forget the action he's seen. Gilbert Arrant, the local lawyer, is the big man around town. His jovial exterior feels so artificial that it makes the reader wonder about why he comes across like a used car salesman. Peter Minks, a reporter, is Gilbert's Yes-Man, which only reinforces Gilbert's silly yet slightly sinister persona. Just like in other stories with anthropomorphic animals, from "The Tale of Peter Rabbit" to "The Wizard of Oz," the choices of animals and names are no accident. Clive's dog face feels trustworthy, but his surname "Slipaway" hints at something else. Gilbert's surname hints at an intensity that isn't shown in the character's bossy but seemingly harmless leadership. And of course, "Fawkes" is a classic trickster character in his ne'er-do-well and yet wily ways.

The pacing of "Wild's End" #1 feels a little slow to build up to the catalyzing event of Fawkes' outburst, but Abnett and Culbard are intent on building up the world before it has to change. The dialogue is at times over the top with all its folksy English exclamations like "Alph, you sweet boy!" or "Marvelous...it's revolutionary!" No doubt, this is part of Abnett's goal, to have this unbelievably bucolic setting set up like a gingerbread house before the demolition crew hits it. However, the over-the-top dialogue of the supporting characters adds to the air of unreality instead of drawing the reader further in.

Abnett's script shines in the small moments, such as Clive's pauses in his replies to Gilbert regarding participating in the annual fete. The pacing is subtle and perfect there, getting across the Gilbert's pushy tactics and his obliviousness to Clive's discomfort.

Culbard's art is also skillful with subtleties of body language and facial expressions. His character design is excellent, particularly with the wardrobe choices. His confident unshaded linework pairs well with his palette of pastels and neutrals. The effect is cheerful and upbeat, but Culbard succeeds at creating a feeling of unease that rises steadily. His palette changes are also well-executed. Culbard uses a more vivid palette of mint and pink for the sequence set in Mrs. Swagger's cottage. The change to more vivid, cooler hues signals a change from daylight to dusk, but it also adds to the suspense as the action speeds up.

"Wild's End" #1 is entirely exposition, but it's a strong beginning, falling short of being stellar only for its slow characterization work, but it succeeds at piquing the reader's curiosity about its characters' histories and motivations as well as what happens next when the aliens make more contact.