In the second half of "The Flash" this season, we'll meet a new character named Gypsy who will help Cisco "Vibe" Ramon develop his superpowers. On "DC's Legends of Tomorrow," two of the regular team members are Vixen and Steel, while on "Supergirl," Martian Manhunter is a major supporting player. Longtime DC Comics fans will recognize that all of those characters -- Gypsy, Vibe, Steel, Vixen and Martian Manhunter -- were members of one of the most derided versions of the Justice League of America of all time, the "Justice League Detroit" era. (The TV Steel is technically based on the Nate Heywood version from "Justice Society of America," the cousin of the deceased Hank Heywood, the Steel from "Justice League of America," but come on, it's basically Steel).

RELATED: Who Is Gypsy? Meet the Future Member of Team Flash

So how do we reconcile the fact that one of the Justice League eras that was most reviled by comic book fans is now the inspiration for such a large chunk of the DC television universe? There appear to be four prominent (and interconnected) explanations.

1. Gerry Conway and Chuck Patton's basic idea was a good one

In 1984, Gerry Conway had been writing "Justice League of America" for more than five years, and as he saw the popularity of the title wane in the early 1980s, he thought he knew one of the main reasons the title was being surpassed in sales by "Legion of Super-Heroes," "New Teen Titans" and "Uncanny X-Men": They had consistent casts of heroes, but, more importantly, the writers of those series had full control over those characters. Paul Levitz answered to no one else when it came to the characters of the Legion; Chris Claremont controlled the destinies of the mutant heroes in the X-Men; Marv Wolfman and George Perez had actually just gotten the complete use of their characters in "New Teen Titans," as a new Robin had been created so they no longer had to worry about coordinating with the "Batman" office for their plans for Dick Grayson (he gave up his Robin identity and became Nightwing).

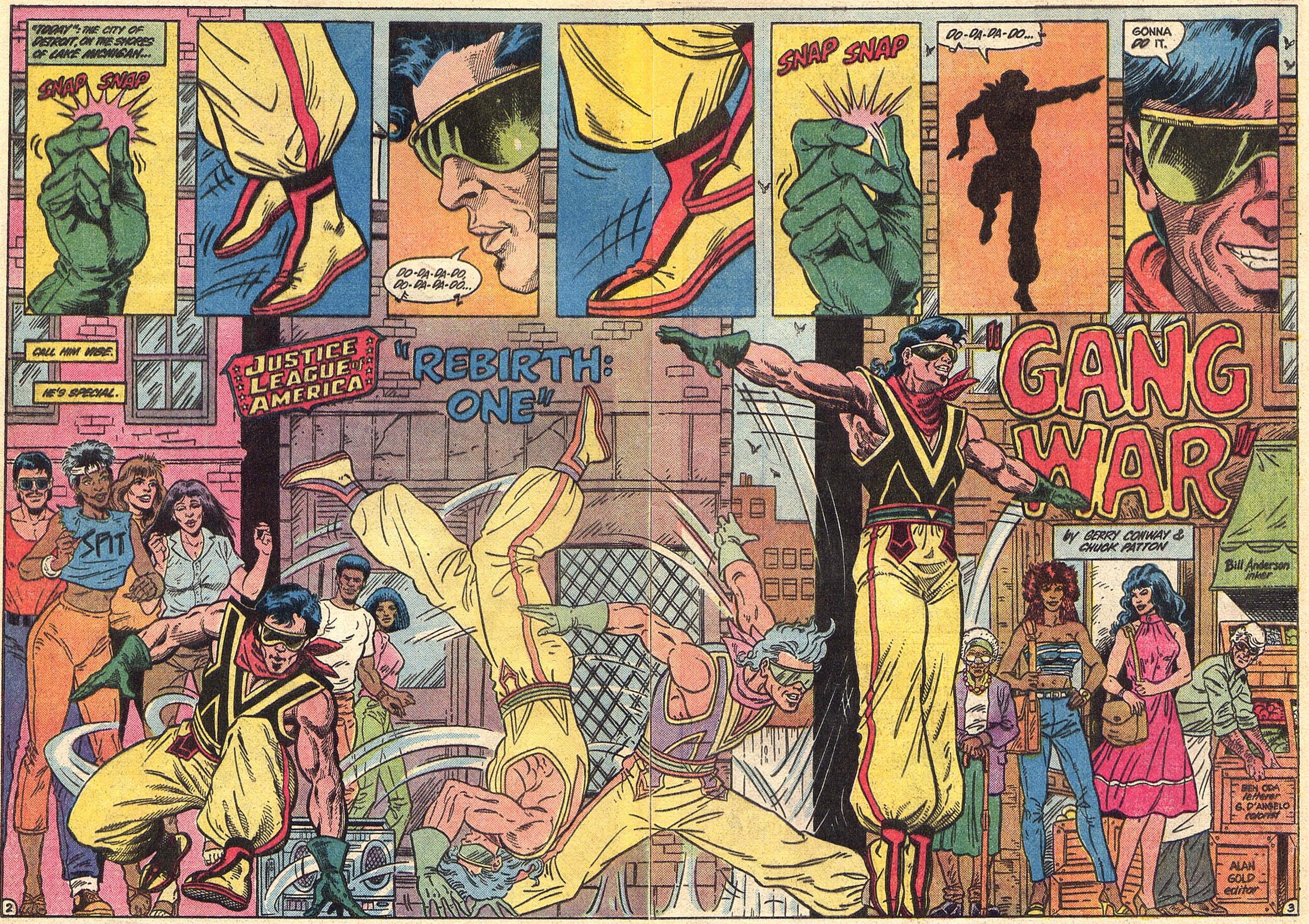

Meanwhile, Conway had been working largely with characters controlled by other titles. That changed in 1984 with the introduction of the new Justice League in "Justice League of America Annual" #2, illustrated by artist Chuck Patton, in which Aquaman disbanded the team and re-formed it only with members who could make full-time commitments. Of the previous incarnation, only Elongated Man and Zatanna could devote themselves to the new League, joined by Martian Manhunter, who had just recently returned to Earth and the League. Amusingly enough, Aquaman ended up unable to commit full-time to the team, and left after a year. The new League was based in Detroit, in a headquarters supplied by the grandfather of new member Steel after the famed satellite was destroyed during an invasion by Mars.

Although Conway was driven to create a comic in which he had control over the characters (and thus, fans believed that memorable changes could be made to the characters, something they knew would never happen with Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman and the others), he also wanted to add diversity and youth to the League. He had invented the African-American hero Vixen in the late 1970s for a proposed ongoing series that was canceled during the so-called "DC Implosion" (when DC canceled the majority of its comic book line due to poor sales, a mocking reference to then-recent ambitious expansion of DC's line of comics called the "DC Explosion"). He then introduced her in the pages of "Action Comics" and brought her back for this new League. Vibe, meanwhile, was one of the first prominent Hispanic superheroes at either of the two major publishers.

When Warner Bros. began to expand its television universe from the initial hit series "Arrow," diversity was a consideration, so such comic book characters as Vixen and Vibe were appealing to producers (it didn't hurt that one of the developers of "The Flash" was DC superstar writer Geoff Johns, a native of Detroit who had already reintroduced a new version of Vibe to the comics). The idea of having diverse characters was smart by Conway and Patton, and it paid off decades later.

2. The execution in the comics was poor

While the motivations behind Justice League Detroit were good and the idea was smart, the execution often left a lot to be desired. The most notable example of this was Vibe, who was one of the first major Hispanic superheroes at DC, but also a walking, talking stereotype. The number of times he says "chu" in just this one page in his first appearance is staggering:

Superstar artist George Perez explained his problems with Vibe's prominent breakdancing to the always awesome Heidi MacDonald of The Comics Journal back then:

Perez: I sincerely say he’s the one character who turned me off the JLA. If nothing else, every character that was introduced was an ethnic stereotype. I couldn’t believe it. I said, “Come on now!” These characters required no thinking at all to write. And being Puerto Rican myself, I found the fact that they could use a Puerto Rican character quite obviously favorable since the one Puerto Rican characters in comic that existed, the White Tiger, is no longer a viable character. But having him be a break dancer! I mean, come on now. It’s like if there were only one black character in all of comics, are you going to make him…

MacDonald: A tap dancer.

Pérez: A tap dancer, a shoeshine boy? Particularly when you’re picking a stereotype that’s also a fad. You’re taking a chance that this guy is going to become very passe, his costume becomes passe because it’s a breakdance costume, the minute the fad fades.

Vixen, Steel and Gypsy did not fare much better in the comics. The sales of "Justice League of America" fell so low that when the title ended (Conway had by then been replaced by John Marc DeMatteis), instead of allowing the characters to simply retire or whatever, DC very pointedly killed off Vibe and Steel. It was one of the most depressing endings imaginable. Then the League was rebooted in Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis and Kevin Maguire with "Justice League International," and Justice League Detroit was mostly forgotten.

But on The CW's "The Flash" Vibe is a well-written, well-developed character that's not even slightly a stereotype.

The same goes for Vixen. So perhaps the most important distinction is that the characters are simply written better on the television shows, which may help to explain why they're more successful in that medium.

3. The characters aren't replacing anyone on TV

Another thing that hurt Justice League Detroit was that its members were replacements for major comic book heroes. The New Teen Titans and the All-New, All-Different X-Men were both replacing titles canceled years earlier. Few readers were saying, "Screw Wolverine and Storm, the X-Men aren't the X-Men unless the high-flying Angel is there!" Similarly, "Cyborg and Starfire are interesting, but I'm not reading a 'Teen Titans' comic book that doesn't have Duela Dent in it" was not a phrase you would hear anyone say in 1980. Vixen, Vibe, Steel and Gypsy, however, were replacing the likes of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern and The Flash.

That's not how these characters were introduced on television; they didn't have that same "replacing our favorite heroes" stigma. Heck, Steel and Vixen on "DC's Legends of Tomorrow" were actually replacing not particularly well-liked characters Hawkman and Hawkgirl, so the reverse was true for them.

4. TV viewers don't care/know if a comic book character is B-, C- or D-list

Going hand in hand with the "replacing superstar characters" stigma was the belief among comic book fans that the members of Justice League Detroit were "D-list" characters, or just jokes in general. That led to people putting the characters down for decades. Heck, the description of this era as "Justice League Detroit" is, in and of itself, a way to mock this era and show that it was filled with "D-List" characters like Vibe, Steel, Gypsy and Vixen.

However, to the general public, nearly all superheroes are unknown outside of the few very famous characters like Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman (and, through the success of "Super Friends," Aquaman, as well). We saw this to a certain extent when the "Green Lantern" film was announced and there were a decent amount of fans who were unfamiliar with Hal Jordan, since John Stewart was the Green Lantern than they knew (from his prominent starring status on the "Justice League" cartoon).

When you don't know who Black Canary is, then how can you know that Vixen or Vibe are generally treated as lesser characters? So that unfamiliarity gave these characters a blank slate with viewers that allowed them to judge the characters solely on how they were portrayed on the screen, and since they were portrayed well, they were accepted wholeheartedly.

The whole situation gives new meaning to the popular phrase, "there's no such thing as a bad character." DC's TV universe is proving that every week.