Fantagraphics’ announced Complete Carl Barks Disney Library, which recently began publication with Walt Disney’s Donald Duck: “Lost in the Andes” is a godsend of a comics project.

The publisher does the heavy-lifting of finding, formatting and even contextualizing the work of one of comics’ undisputed (and, in some way, unrivaled) masters and putting it all together in an easy to find and read source, making Barks’ influential work available to casual readers to either easily finally find out why The Good Duck Artist has the reputation he has, or to discover his work for the first time.

Before cracking the cover, I will admit there was one aspect I was a little leery about. Because so many of Barks’ stories dealt with the Ducks visiting exotic lands, because the stories in this collection were produced between 1948 and 1949 and because Disney doesn’t exactly have the most sterling reputation when it comes to representing diverse nationalities or ethnicities, I was sort of concerned about what the lily-white ducks would be faced with when they journeyed to South America or Africa. Or, more precisely, how Barks would present what they would be faced with.

Reading Will Eisner’s Spirit comics and being confronted by his Ebony White or Osama Tezuka’s work and seeing the various racial stereotypes that pop up in it can be a bit like finding a fly in your soup—by biting down on it. It’s great stuff, but there’s that extremely unpleasant moment you could have done without, you know? (Also, while I haven’t read it, it’s my understanding that Tintin may have had at least one less than politically correct adventure in the Congo).

Nevertheless, I was happy to see that Fantagraphics didn’t edit Barks’ work to make it less offensive—they didn’t go the route Papercutz went with Peyo’s Les Schtroumpfs Noirs, which became The Purple Smurfs—and present Barks’ work cultural warts and all.

And I was happier still that it wasn’t that bad. Certainly some of the depictions would seem hideously if drawn in 2011, but there Barks treats his subjects of color with a decent amount of respect, and, on a spectrum of either Great Old Cartoonists Drawing Racial Stereotypes or even Racial Stereotypes in Disney Media, the stories in this collection fare fairly well, more Aladdin than Song of The South or Dumbo.

The title story sends Donald and his nephews to Peru in search of square eggs, where the locals all consider the ducks a little crazy, and react to their quest by either making fun of them or trying to swindle them.

The eggs come from the lost valley of Plain Awful, a square city where everything, including the people, are more square than they are round. They are such a fantastic people, invented from whole cloth, that it’s hard to find offense in their portrayal. In design they are as cartoony as the cartoon ducks, and their culture is…peculiar. They speak exclusively in the accent they learned from their last visitor, in 1868 “Professah Rhutt Betlah, frum th’ Bummin’ham school of English.”

In “Race to the South Seas,” Donald and the nephews race lucky cousin Gladstone Gander to rescue Uncle Scrooge, whose boat reportedly sunk in the area (not necessarily out of goodwill, but to make sure they are treated good in Scrooge’s will).

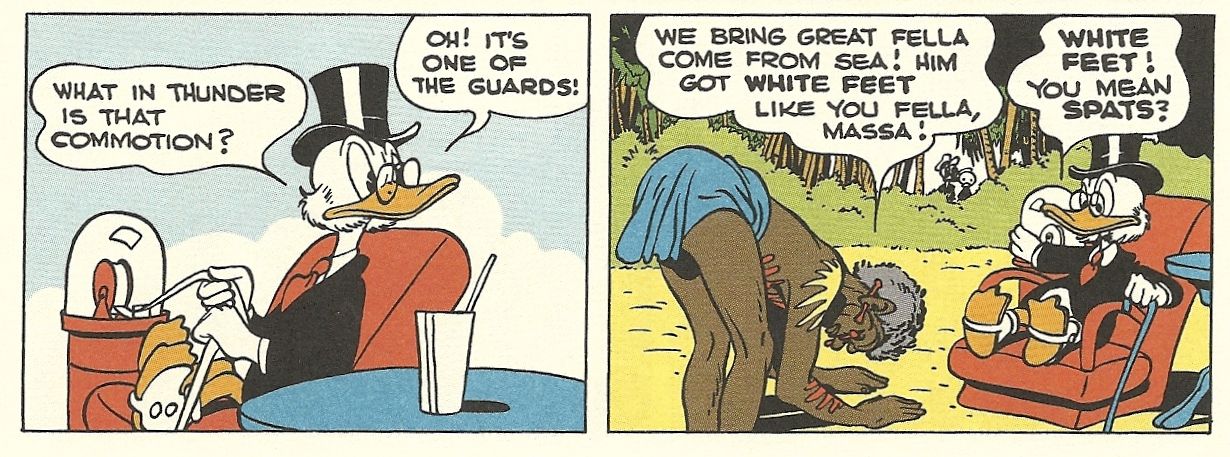

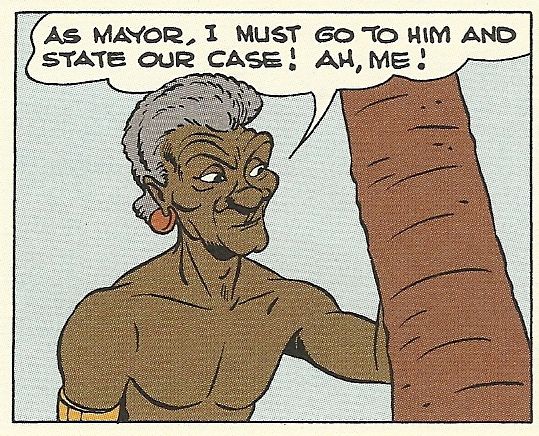

Two island cultures are met in this story. The first is that of Coca Bola, a people legendary for their hospitality—to the point they allow a guest to eat every single piece of food they have, save their coconuts. Barks draws them as real people, which is actually a bit disturbing in the world of ducks and dogs (the Peruvians he drew also looked like real people, but they had dog-noses to separate them from humans). In addition to a more-or-less representational depiction, they get the better of Donald. Having learned the errors of their generous ways by Gladstone, they now great visiting white ducks with clubs instead of platters of food.

The members of the other island culture is referred to as “cannibals” by Donald, and they throw spears, have bones through their noses, worship spats and talk like this: “Ola Eela Booka Mooka Bocko Mucka!” Perhaps the main saving grace here is that Barks again draws them as real people…again, more real than the anthropomorphic animal characters that populate the Disney comics world.

The final, and most troubling, of the stories included here that deal with culture clash is “Voodoo Hoodoo,” the title of which alone is enough to clue a reader in on where it might be going.

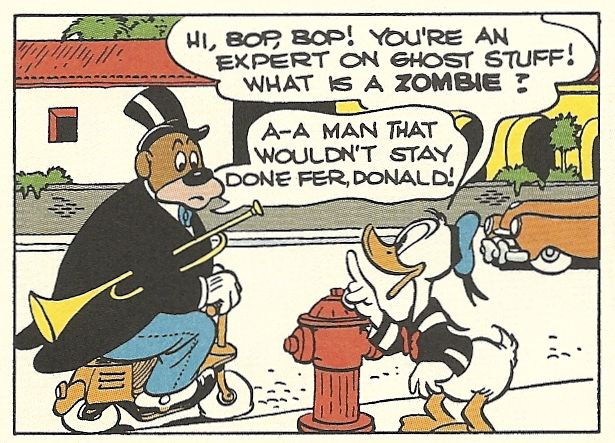

The story opens with a scene of Donald walking around what is apparently the “black” neighborhood of Duckburg, with all of the various dog characters colored dark brown. They are all talking about a zombie being sighted in town (Remember, this is 1949, so it’s an I Walked with a Zombie zombie, not a Night of the Living Dead zombie).

After a few panels, Donald stops and asks a passerby he apparently knows what all this zombie talk is about. In the story notes at the end of the collection, Jared Gardner writes that this is the “first character in Duckburg coded explicitly as African American.”

Writes Gardner:

Bop-Bop displays the contradictions at the heart of Barks’ engagement with the zombie story. On one hand, Bop-Bop epitomizes the racist stereotypes of the day: he is drawn with exaggerated lips and speaks in an exaggerated “negro” dialect straight out of the minstrel tradition (and most immediately familiar to readers in 1949 from the popular weekly radio series Amos ‘n’ Andy). On the other hand, he is also the character Donald turns to for the inside information on zombies, suggesting his access to a body of knowledge not at the disposal of the rest of the community who are baffled by the sudden appearance of a zombie in their midst.

The zombie himself is Bombie, who is also drawn according to racist stereotypes: Big ears, big lips, and with a pierced nose. Bombie has traveled to Duckburg to present Donald with a cursed voodoo doll and then, mission accomplished, he just sort of stands around, until the nephews decide to adopt him and help return him to his African homeland.

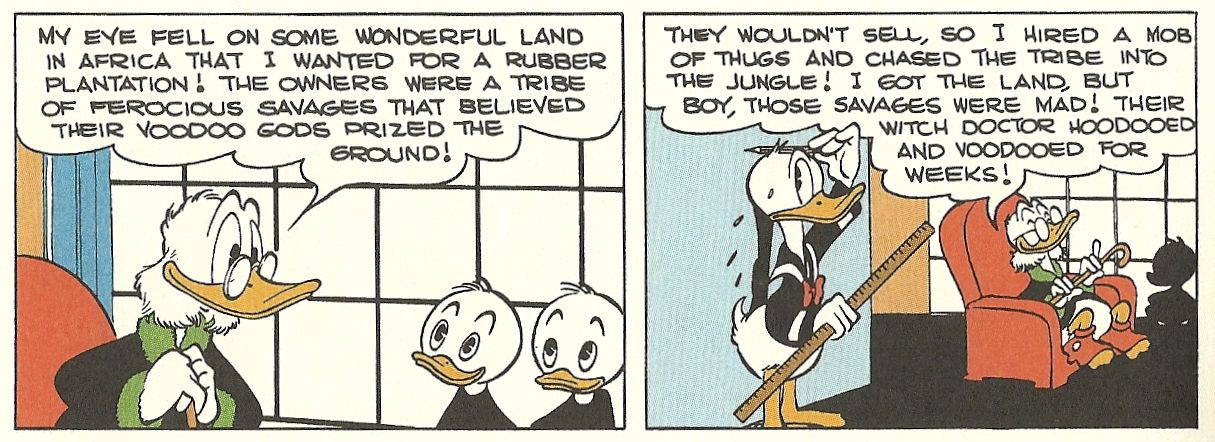

Bombie was created by the voodoo witchdoctor Foola Zoola, who is another horrible stereotype, as is his tribe. The only positive thing that can be said about Barks portrayal of Africans in this story is that Foola Zoola and company are at least given a good reason for their vengeful actions:

To avenge the loss of their land and their exploitation at the hands of the greedy American imperialist Scrooge, Foola Zoola sent Bombie after him with the voodoo doll, but Bombie gave it to Donald instead, as Donald resembled Scrooge at the time Scrooge was in Africa.

Now, “it could have been much worse” is a terrible defense of racist stereotypes, not much better than, “that was a different time.” But it is somewhat comforting to know that such choices come from ignorance instead of a well-informed choice (Barks didn’t travel to Africa to draw that story, and his ability to research would have been limited to what he saw in Hollywood movies or in other cartoons and comics).

It’s more comforting still to see Barks struggling with an issue like imperialism and exploitation in the midst of a silly little adventure story. The art in “Voodoo Hoodoo,” much more so than in the other stories involving native cultures, may have included some unequivocally racist imagery, but at least the story assigns evil behavior degrees, and different exponents.

The villain of the first page turns out to be the most innocent character in the story. His boss is the real villain. But then, that villain was simply trying to reclaim what was rightfully his from the villain that stole it from him.

That moral ambiguity doesn’t forgive the drawings, of course, but I’ll take what I can get here.

And of the above stories mentioned, that’s only three of the four long-form adventure stories in this collection, which also includes nine 10-page short stories and seven one-page gags, as well as a biographical introduction and the aforementioned story notes. They account for but a small part of a great big book full great big comics from a great big talent.