Eric Stephenson means well. As publisher of Image Comics, and even before he held that position, he's often called out for change in the comics industry. I love these calls to action, even if they're not always graceful; change usually isn't. Most of us agree that changing the comics industry for the better is in everyone's best interest, but how to change it and how we define better is when things get messy. I'm usually in agreement with what Stephenson is saying, but his speech last week at the ComicsPRO annual meeting was jumbled and tripped over itself when it came to licensed comics.

Stephenson got hung up on a significant sector of comics publishing, and I think it muddied his larger message. In his speech, as I'm sure you've seen re-quoted multiple times by now, he claimed that licensed comics like IDW's Transformers and GI Joe, and Dark Horse's Star Wars "will never be the real thing." In the lead-up, he also explained there are "only two kinds of comics that matter: good comics and bad comics." Now, he never outright said licensed comics are in the "bad" category, but some certainly viewed that as the implication.

His argument is that comics should rely on original ideas to produce original content, a point he underscored by pointing to the perennial bestseller The Walking Dead and the fast-growing Saga, both coincidentally published by Image. I agree original comics are where the magic can happen, and where the creators can most benefit. But that doesn't mean everything else is by default a waste of time.

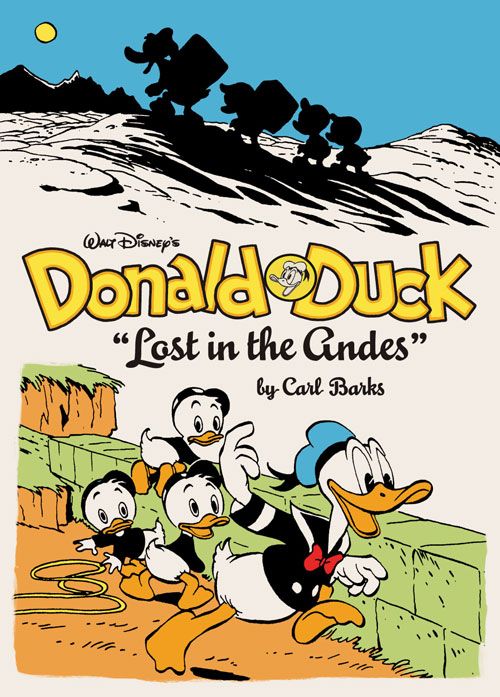

If that were the case, we would never have experienced the work of one of the acknowledged masters of the comics art form, as the majority of Carl Barks' work on Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge and other titles was published by Dell Comics through a license with Disney. Don Rosa is similarly recognized as a magnificent artist and storyteller. Yes, there was a lot of unfortunate mistreatment regarding credits, rights and salary that wouldn't have existed had those two creators produced their own original comics. But both men wanted to work on those properties. For Rosa, it was a dream come true. Who are we to say the results of that dream aren't real?

Of course, a Carl Barks and a Don Rosa don't come along every day. And the stigma with licensed comics is that they are creatively restrictive because the owners of the property have to sign off on everything. That's not always the case. Scott Shaw! is working on the Annoying Orange graphic novels for Papercutz, and he's doing some weird and funny work in those silly books with minimal interference. Such projects will never give the creative freedom of someone making comics they fully own, but more and more creators are largely being left to do what they do best. Licensed comics are also employing a significant number of creators right now, many of which either don't otherwise have the financial means to risk on a creator-owned book, or don't have the interest in that kind of project, as in the case of Barks and Rosa. As much as I'd love Scott Shaw! to do more Now It Can Be Told installments, I'm willing to bet they don't pay the bills as well as a regular gig from a publisher like Papercutz. The debated reality of those comics stories translates into very real jobs for a lot of people.

But what exactly did Stephenson mean when he said licensed comics "aren't real"? He obviously recognizes they exist in time and space; he was speaking from the consumer's point of view. The majority of casual and more enthusiastic fans of Disney were first exposed to those characters through animated shorts or feature films. That might be debatable these days, but certainly in the 1940s when Barks was starting out, that was the case. The theory is that these fans are only interested in experiencing those characters in the medium in which they first encountered them, and a transition to a different medium is seen as derivative, something "less than," and most just won't do it. So we shouldn't bother.

It's difficult to prove that theory is the rule for all consumers of entertainment, but this notion is not without precedence. That concept usually resonates with longtime readers of superhero comics. These readers, especially the older ones, are often concerned with what "counts" toward the "real" stories being told about those characters. That's why Marvel's What If-? is doomed to occasional miniseries or one-shots tied to big events; an ongoing series is doomed. Even the What If-lite X-Men spinoff Exiles, which kinda-sorta "counted," couldn't make it. There are too many superhero comics to buy that do count toward the epic narrative -- who can afford to buy something else on top of that? If DC's Elseworlds labeling had existed at the time to eliminate all doubt, I wonder whether Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns might just be a cult favorite today. So this idea of what's "real" has a rich legacy among the core of Stephenson's audience for his speech, direct market retailers.

But does it translate to the outside world? I think the answer is often yes, which might sound like I agree with Stephenson and comics shouldn't bother with licensed comics. But it's not quite that simple.

When I was young, I shared the thought that the comics versions of the cartoons I loved "didn't count"; they weren't the "real versions." I was a child of the '80s, so my world was all about Transformers and GI Joe and a number of other toy properties before and after them. (By the way, it's important to note that these are toy properties first. While not the case with Star Wars, the original medium of the first two licensed comics properties Stephenson mentioned was technically toys, not TV. But more on that later.)

I was not interested in licensed comics. But without licensed comics, it's extremely likely you wouldn't be reading this. They are what got me reading comics. So what changed? Only the most emotionally scarring moment of any kid of the summer of 1986: the death of Optimus Prime. The unexpected offing of the main character and many other favorites in the animated Transformers: The Movie, which took place in the far-flung future of 2005, left a lot of questions about what the upcoming third season of Transformers would look like. I held out hope that in the fall, the season premiere would go back to the present time of 1986, and all my favorite characters would still be alive. Not so. The show continued on with an almost entirely new cast, and all my cartoon friends were gone forever.

Or were they? I remembered seeing Transformers comics in a convenience store, and the original cast of characters were still there. Well, it wasn't "real," but at least I'd get to see them again. The next time my mother went to that convenience store, I asked her to buy me an issue. The great irony is that by the time I got to the comics, Optimus Prime had been killed there too. But at least it was set in the present and other familiar characters were around. So I begged for a subscription and slowly got hooked. After a few years, I started to get GI Joe too. By 1990, Marvel's in-house ads had subconsciously bewitched me and I started buying a superhero title. By the next year, I was buying virtually every book even tangentially connected to the X-Men. From there, I explored different publishers and genres, and my fascination with the comics art form has yet to be exhausted. I am as real a comics fan as they come. For me and many like me, licensed comics were the gateway, they were the familiar hook that lured us into the new and original. And because of that, they hold immense value.

I recently re-read a lot of those old Transformers comics. I admit, they are pretty weak (although, the last third of the Marvel series redeems the whole thing). But they were admittedly meant to entertain children, and there is a spark to them, a creativity and world-building that grabbed tens of thousands of kids just like me. That creativity was so rich, that it was the basis for the very cartoons that are supposed to be more "real." Most of the names, personalities, abilities and other unique attributes of both the GI Joe and Transformers characters were created by Marvel's creators. Larry Hama is single-handedly responsible for at least the first decade of characters that have inspired stories in multiple media, many of which he himself has written or influenced. His work on the original GI Joe comic book is an impressive, sprawling epic worthy of any superhero universe. In the case of GI Joe, the comics are the real thing and the first thing: GI Joe #1 was released in summer 1982; the animated series began the next year. Writer/editor Bob Budiansky was responsible for a good portion of the Transformers characters. The first issue of the Transformers comic predated the first episode of the cartoon by several months. In both of those instances, Stephenson's first two examples of non-real comics, the comics actually are the first version.

But not everyone knows that because more people watch TV and go to the movies than read comics, even in the heady '80s when Transformers and GI Joe comics were selling very well for Marvel. That's the case even more so today, and the same thing is happening to one of Stephenson's examples of comics originality, The Walking Dead. It may be hard to believe in our circles, but not everyone knows that the zombie TV show comes from comics. And even if they do know, their perception is still that the "real" version is the TV show. I know people who have tried the comic after being educated about the "real" version of the TV drama they love, and they couldn't get into it. It just didn't feel right, a classic case of it not being the "real" version for them. See, the trick is that just like with those '80s properties having strong roots in comics but being seen as TV and toy properties, we don't get to decide what the larger public ends up deciding is "real," regardless of the facts. It's the same reason people were angry about a white Green Lantern when the movie was cast -- the John Stewart version from the animated Justice League series was their "real" version, because they never knew about the decades of history that said otherwise. It's the same reason that even the animated version of Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis is the "real" version for a good number of people.

It doesn't matter if it's superhero comics from the Big Two, licensed comics, creator-owned or small press or indie -- it just matters what people experience first and like the most. Comics don't need to argue over what's real. Every comic is very real to someone. To achieve Stephenson's, and the industry's, real goals, of reaching more readers and new readers, comics need to keep looking for ways to be experienced first, and be the best experience.