Originally released in 1898, H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds has now been an unshakeable pillar of the science-fiction genre for over a century. Telling the tale of a then-current invasion of the planet Earth by Martians seeking a new home, Wells' ubiquitous story has served as the foundational baseline for nearly every work of alien-centric speculative fiction ever since. As with any iconic work of literature, especially one so full of intrigue and compelling visual ideas, Wells' novel has been adapted numerous times into other mediums.

While the novel passed out of copyright a few decades ago and has resulted in a variety of cheap knockoff adaptations sporting the title since, there are three equally iconic adaptations of the work spread out across the century following its release: Orson Welles' 1938 radio drama, Byron Haskin's 1953 film and Steven Spielberg's 2005 film. Together, these three adaptations of War of the Worlds make up a trilogy of works that each brought urgent relevancy to Wells' decades-old text by rooting themselves so wholly in the fears of their modern time.

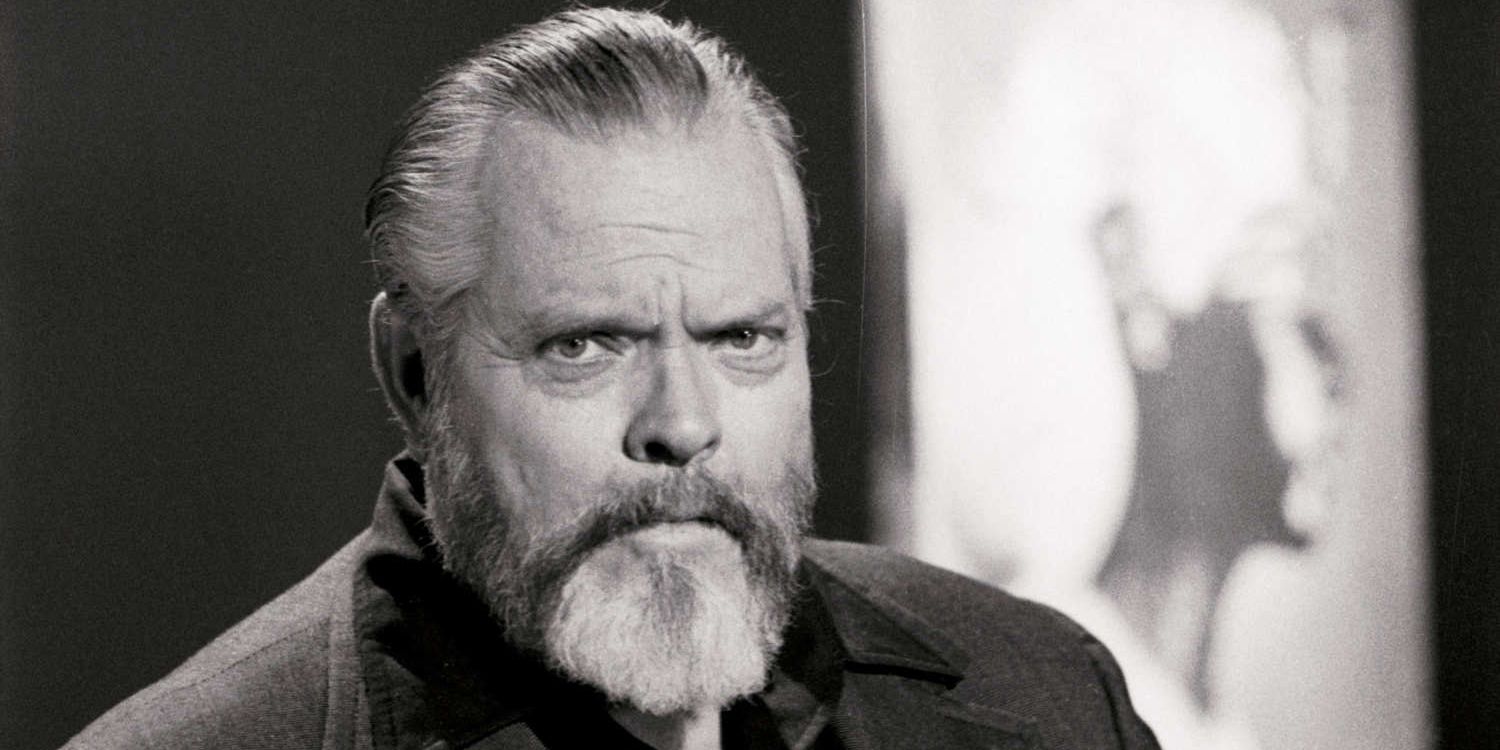

Orson Welles' War of the Worlds Horrifically Fooled a Nation

The date was October 30th, 1938. In the ten years since the national economic collapse of the Great Depression, American homes had become increasingly reliant on radio as their sole source of news. Regularly scheduled programming was constantly being interrupted in the name of delivering breaking news bulletins. In 1937, families around the country gathered around the radio to hear the breaking live-from-the-scene bulletin of the Hindenburg disaster. For 18 days in September of 1938, Americans dialed in to hear coverage of the Munich crisis, including Hitler's impassioned speeches. So on October 30th, 1938, not only were audiences accustomed to hearing devastating news on the radio but they had practically been conditioned to believe in it. It was on this night that Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater delivered their radio drama adaptation of War of the Worlds.

Welles' War of the Worlds deliberately weaponized the radio format, with him and his Mercury Theater collaborators staging setpieces to invoke the immediacy of the news bulletin formatting. Actor Frank Readick even infamously modeled his news reporter's delivery on Herbert Morrison's searing coverage of the Hindenburg disaster. The broadcast ultimately caused a nationwide panic, with thousands of listeners allegedly believing the alien invasion to be real, to the point that Welles had to publicly apologize the next day to assuage legal concerns.

And it's easy to see why. Welles' War of the Worlds is phenomenally well-staged, transferring from the 1898 English countryside setting of Wells' novel to 1938 rural America and very methodically utilizing the form to tap into the exceedingly modern fears of the nation with aplomb. Welles would go on to become one of the most acclaimed filmmakers of all time with masterworks like Citizen Kane, Macbeth and F for Fake, but the legacy and infamy of this invasive broadcast that made an entire nation believe in a Martian invasion remained.

Byron Haskin's War of the Worlds Exploited Nuclear Terror

In 1953, with the impact of Welles' version still weighing heavily in the public consciousness and after decades of false starts, producer George Pal felt the time was right for a proper film adaptation. America as an audience had fundamentally changed since 1938. Radio had begun to give way to television, Americans had witnessed the tragedy of Pearl Harbor and endured the entirety of World War II, and the atom bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, resulting in a wave of nuclear fear spreading across the globe. This is where Pal and director Byron Haskin's adaptation takes the baton from Welles and finds an entirely new generation's fears to exploit.

Haskin's War of the Worlds begins with a montage of footage of World War I and World War II before promising a coming struggle "fought with the terrible weapons of super-science, menacing all mankind and every creature on Earth" to be known as the War of the Worlds. This opening is deliberately cut together with narration to be evocative of the wartime newsreels that American audiences had become all too accustomed to seeing as their predominant source of news during World War II. Haskin's version keeps the rural American setting of Welles' version and a good portion of the story beats of Wells' novel but does largely eschew its source materials when it comes to its aesthetic and designs. The Martian war machines are not the overt tripods previously described but rather coded in a fashion deliberately reminiscent of the UFOs plaguing the nation's headlines. Similarly, the story is updated to include the modern military's extraneous efforts to fight back against the Martians, including the army's artillery and even the use of an atomic bomb, most of which is visually captured within the film by repurposing actual World War II footage.

Just as Welles' War of the Worlds had so precisely pinpointed the greatest fears of its era and found them within the text of Wells' novel, so too did Haskin's War of the Worlds. Nowhere is the difference between these eras more precisely demonstrated than in the two versions' disparate endings. The novel's ending has always been a bit controversial, with the Martians ultimately defeated not by man's efforts but by diseases present within Earth's atmosphere that they were unaware of. Welles' broadcast ends with great uncertainty, leaving audiences in the wake of the devastation but without even an ounce of solace or closure. Conversely, Haskin's film ends with heavy implications both narratively and visually that the Martians' defeat is a result of divine intervention, literally closing on a shot of the sun rising on a chapel that provides the characters sanctuary.

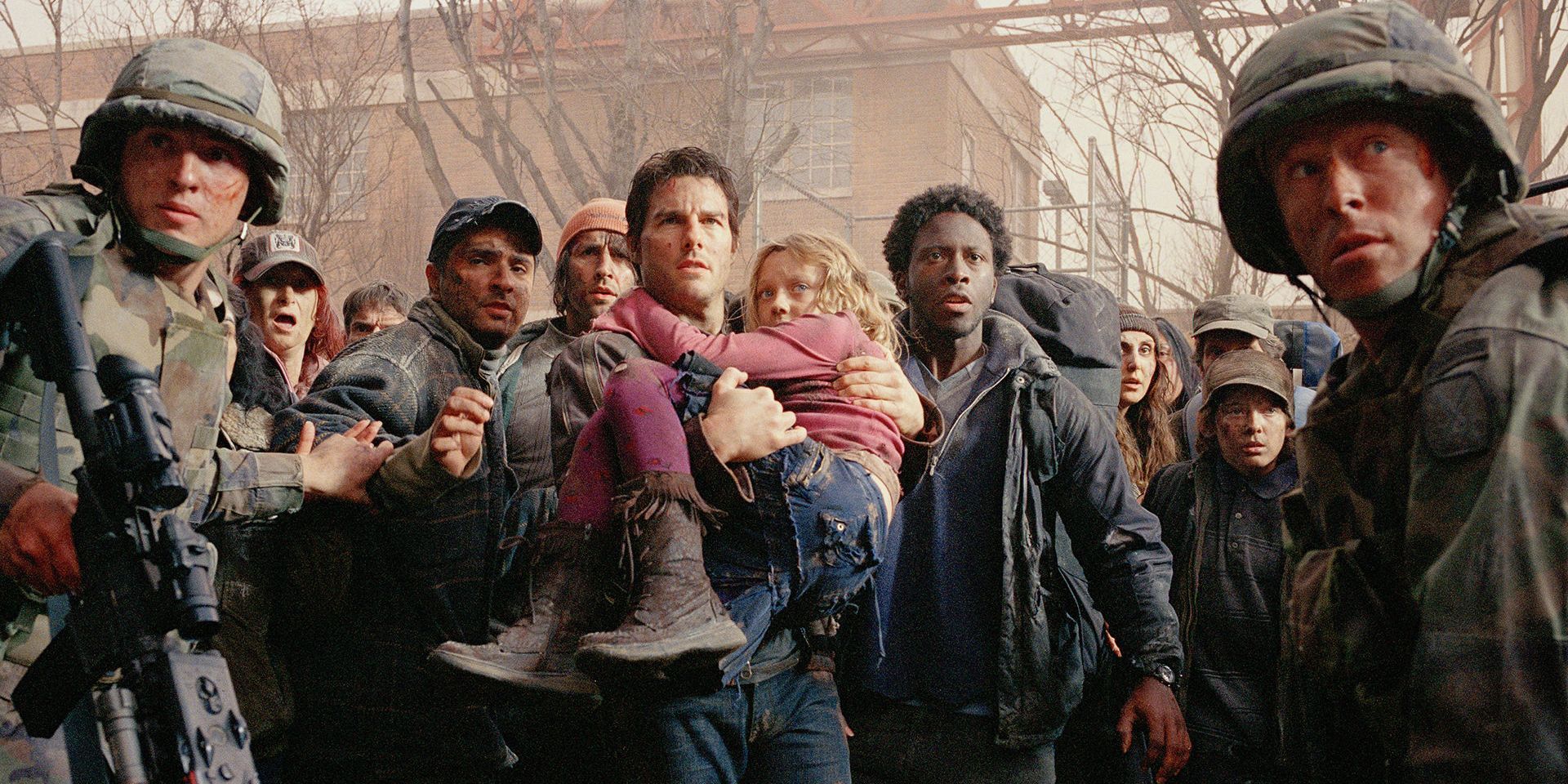

Steven Spielberg's War of the Worlds Interrogated Post-9/11 America

If that much had changed in America in under 20 years, then the America that Steven Spielberg's film was released to in 2005 was nigh immeasurably altered by 50+ years of history. Most pressingly, Spielberg's War of the Worlds was made in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 and remains one of the most potent distillations of the bleak paranoia of the era. Whereas Haskin's film had been captured in vibrant Technicolor, Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kamiński opted for desaturated colors and harsh lighting, evoking news coverage of the terrorist attacks. Where every previous protagonist of the story had been a man of science, Tom Cruise's Ray is a blue-collar, largely unlikeable everyman. While Haskin's film ended with characters finding reprieve in a sanctuary, Spielberg's film obliterates a chapel in its opening setpiece.

The resulting film is a harrowing and pessimistic indictment of the times, one in which the ending feels less like a blessing and more like a death sentence. A world that humanity has helped to make so oppressively lethal that nothing can truly survive. Spielberg's film is one of Wells' novel's opening lines come to life: "we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought."

Across generations, War of the Worlds has remained an iconic and invasive tale; one that masterful storytellers are drawn to. From Wells to Welles to Haskin to Spielberg, War of the Worlds has served as an unbelievably pressing allegory for the fears of a nation time and time again.