While villains have been haunting young children for more than 50 years, the darkness unleashed is tolerated because they are tempered and ultimately thwarted with the help of beautiful damsels in distress. But what if there was no true beauty -- only pure, unscrupulous darkness and a menagerie of tiny people trying to make sense of a world, which has the body of a dead girl as its nexus point?

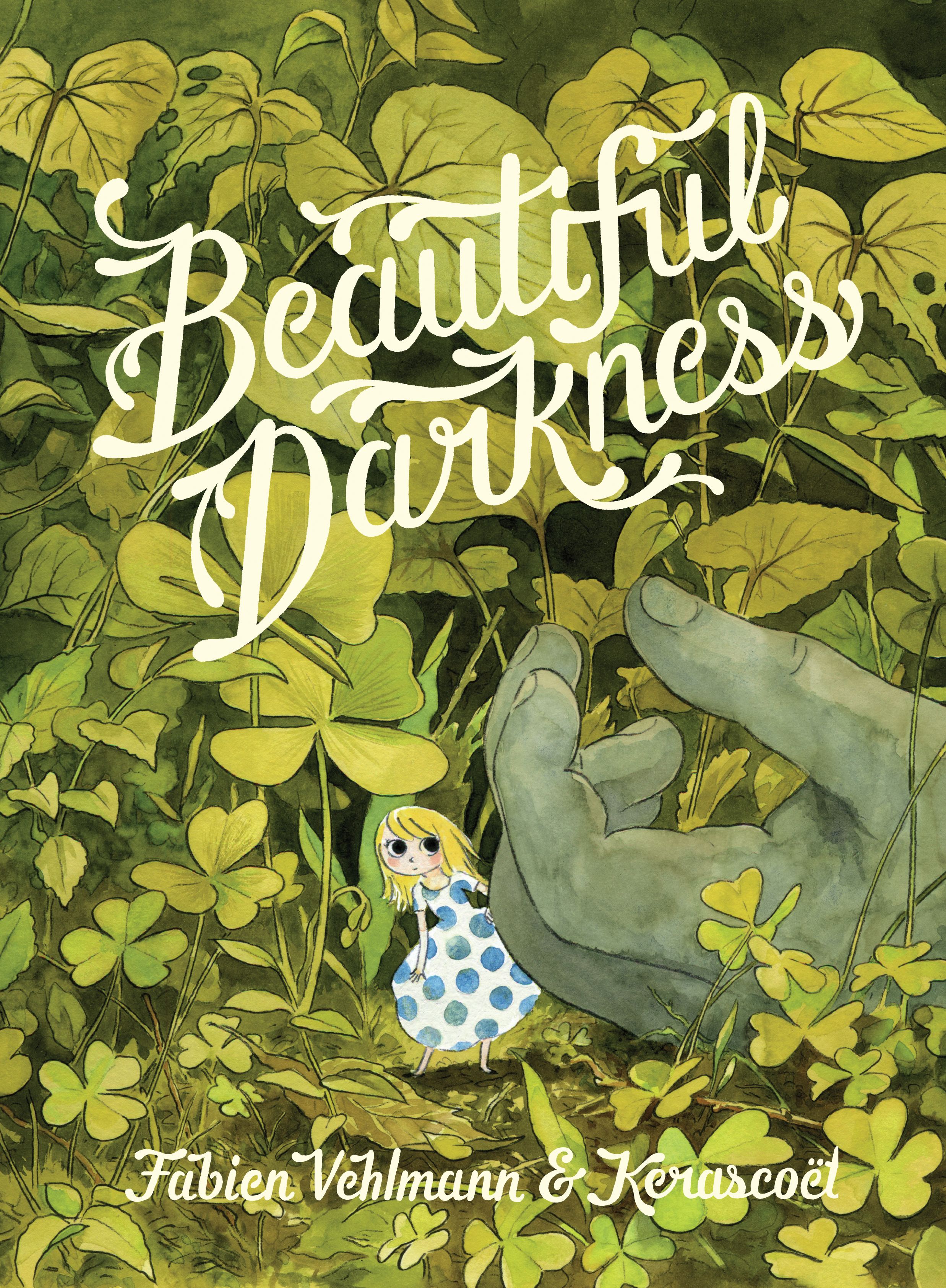

That's the conceit of "Beautiful Darkness," published by Drawn & Quarterly, by Fabien Vehlmann and Parisian artists Kerascoët. Vehlmann, who created "Green Manor" and "Seuls," has been nominated for multiple Angoulême International Comics Festival awards while Kerascoët is the pen name of artists Marie Pommepuy and Sebastien Cosset, who have collaborated on several groundbreaking projects, including "Miss Don't Touch Me" with Hubert.

RELATED: Vehlmann and Jason Visit "Isle of 100,000 Graves"

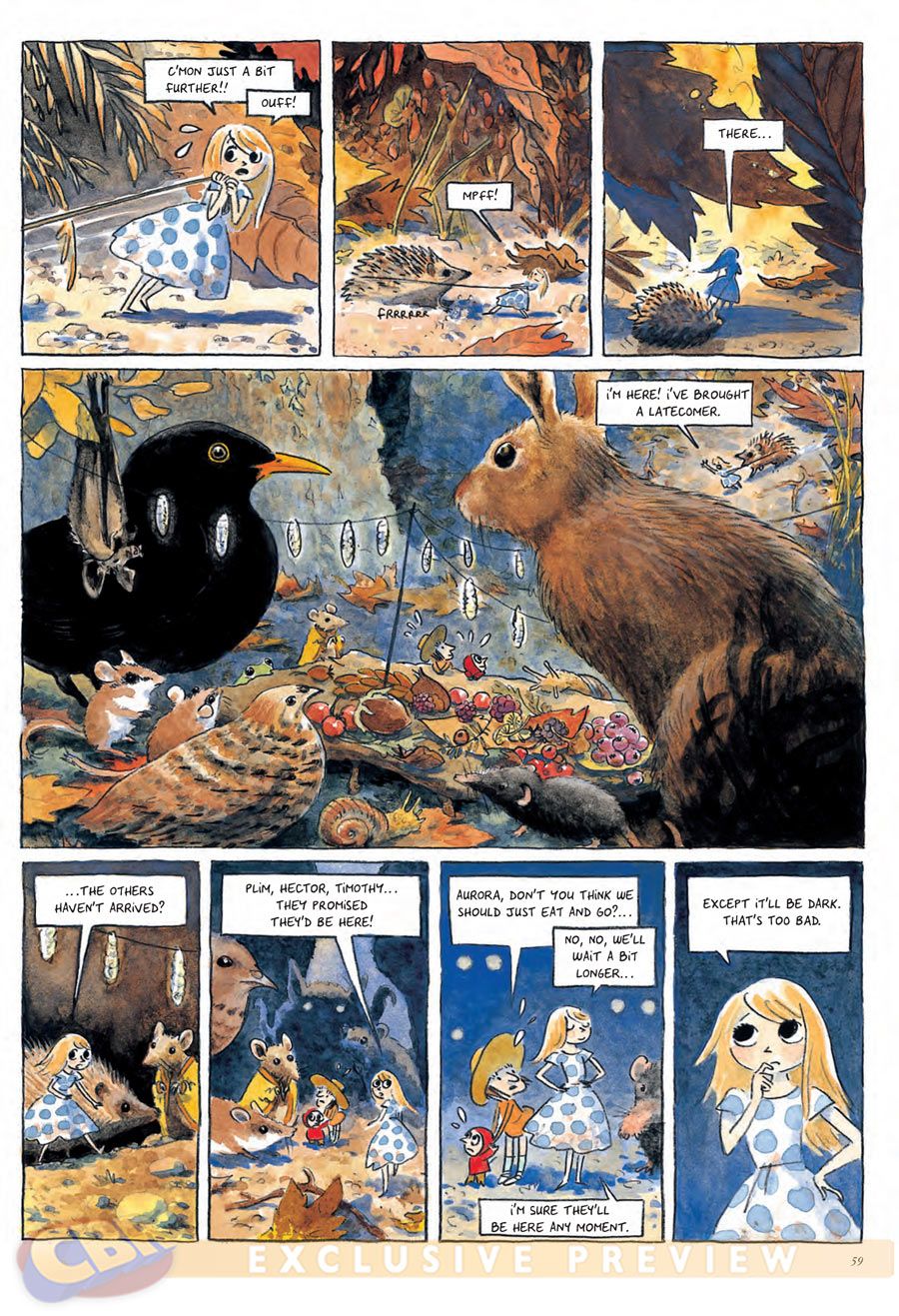

As the story opens, Aurora is having a tea party with Hector, the prince she's been dreaming about, when suddenly, the young lovers are doused in a literal blood bath, struggle terribly, only to emerge from a skull in the middle of the woods.

In this exclusive first North American interview, CBR News spoke with Vehlmann and discussed the book's "harrowing look at the human psyche and the darkness that hides behind the routine politeness and meaningless kindness of civilized society."

CBR News: Fabien, how did the story of "Beautiful Darkness" begin and develop over time?

Fabien Vehlmann: As perhaps you know, Kerascoët is actually a two-headed artist. It's a couple -- Marie Pommepuy and Sebastien Cosset. And the very first idea came from Marie. She shared approximately the first seven pages of the project, the very first moments between the prince and the princess. Things get very weird between them and then we realize that there is a corpse so that whole introduction to this story was in Marie's sick head. [Laughs]

We are friends and she asked me at that moment what I was thinking about that story, because she wanted to write her first script and to draw it with Sebastien. She wanted to know if it was worth it -- if I thought it was a good idea. When she told me about that very strange introduction, I said to her that it was very sick and very weird and that I loved it. [Laughs] I could really feel the potential of the story and its beautiful darkness. It's cruel and powerful, and that's exactly what we try to find in a good script: not only good emotion and good feeling, but something that shakes you -- not like the victim of the story, but leads you into a strange feeling at the end of the reading.

I said to Marie that I would be delighted to help her write the story and then I became the script doctor. Then, she proposed that I become the co-writer of the story because she was not at ease with dialogue.

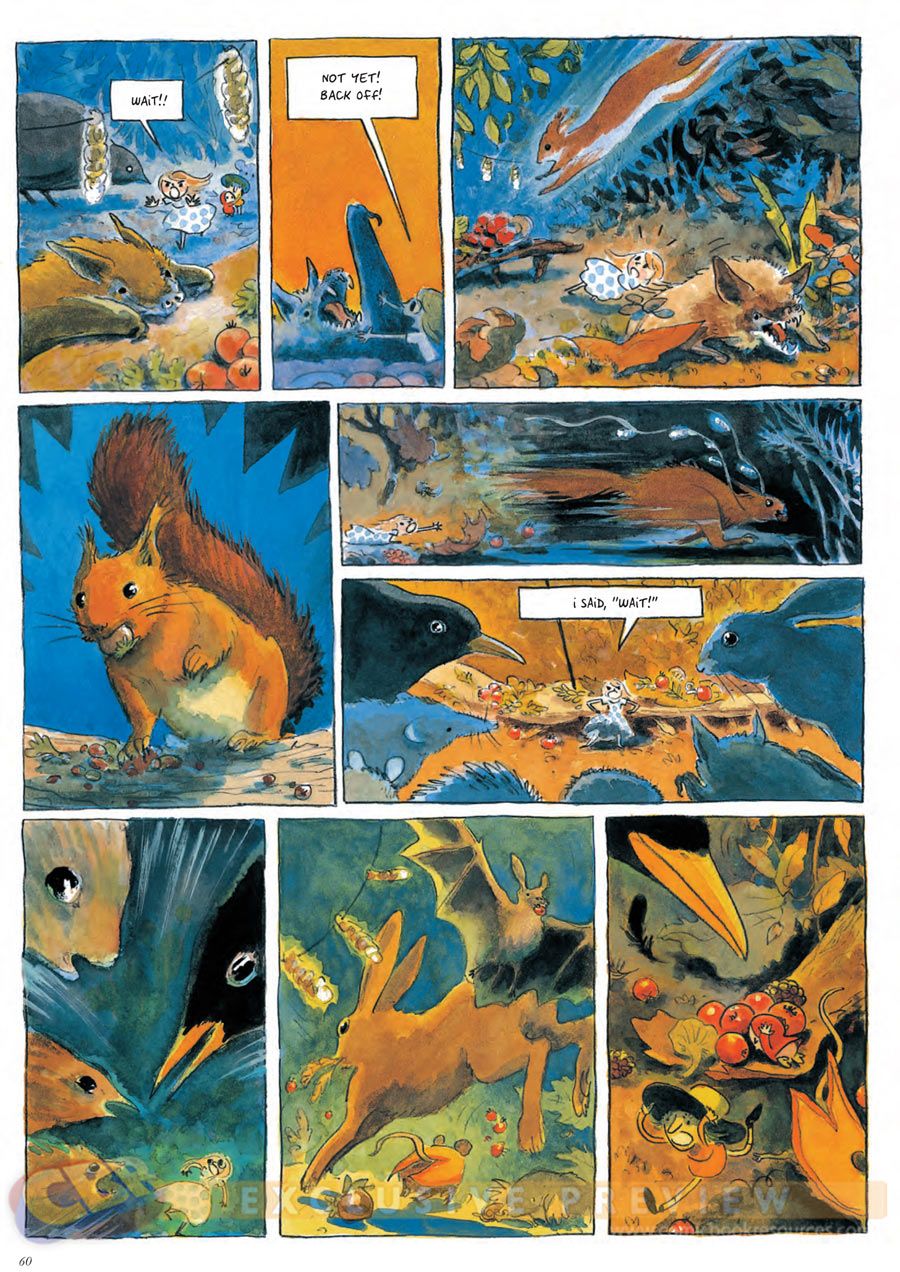

Our common point of view was that we didn't want to explain too much because we didn't want to give the reader all of the keys. We also wanted to tell a very dark fairy tale, but not for children. It's very clear that this is for adults even if we talk about childhood and fairy tales. We talk about the cruelty of childhood and the cruelty of life in general.

Despite all the cruelty involved, it sounds like you enjoyed the collaboration.

Oh yes, very much so. The main thing that I brought to the project was the unity of time and place. That is to say, a lot of things were very clear in Marie's head but, for example, she thought about making the little puppets or creatures -- I don't know exactly what to call them -- leave the forest and go to the city. I really insisted, because I thought that it was very important, that they should stay in the forest for the whole story. For me, it was just like a little theater and strangely enough, the setting is the corpse of a little girl. It's not like a real little girl. It's more like a suggestion to the reader that something cruel has happened and this corpse and it's rotting in front of you. It's more like a memento mori. Remember, you are going to die. It's exactly the same here. You are not obliged to think about it all of the time but it is here -- in the setting. Each time you look at it, you remember there is a corpse in the forest.

I also proposed that the time of the story would be one year -- the four seasons. For me, it was perfect to tell what we had to tell which were the story and the life of one of the little puppets.

You and Kerascoët have wonderfully Disney-fied a horrendous story about the human condition using, as you call them, cute and cuddly puppets to tell your tale. Do you think that we, as humans, mask our true emotions and feelings every day by using similar distractions because the world is a pretty dark place when you sit and think about it?

Yes and it's especially true when we are talking about our memories of childhood. If you have experienced someone talking about his or her childhood, most adults will say it was great. It was like paradise on Earth. But if you really look at real children in a school, you will realize that cruelty is already there. It is not a paradise at all. It can be very, very tough. And as adults, we don't want to see some of the undercurrents that human beings face from their childhood because it reminds us that it was not very fun.

That is what I had to explain to my mother when she read "Beautiful Darkness." I had to explain that this wasn't my general point of view on life but just one certain point of view on life. That is to say, sometimes, I realize that those undercurrents of cruelty are here, it's very present and sometimes, fortunately enough for me, I forget it [Laughs] and I tell jokes and I'm watching TV and everything is great and I am sure that we are going to make it, but this special book tried to stop a minute and have a look at the darkest part of humanity -- and not only of humanity, but a look at the darkest part of the world.

What is funny is that for the rest of the world, for example, in nature, there is no cruelty. There is not such a thing as cruelty. If a rabbit in the forest dies, it's just a corpse and then it's the cycle of life and everything is great. There are little flies all around the corpse and we're not going to be crazy about that but here -- it's exactly the same except it's the corpse of a little girl. And then it becomes something totally insane for us. It is unbearable for the human spirit.

That's why we wanted something like the symbol of innocence and the little girl in the forest. It's the perfect symbol for that. It could be natural but it's just the opposite. It's a scandal in the biblical way of using that word. You can't tolerate it. It's more than a human being can tolerate.

What's interesting is that we never explain why this little girl died in the story, but you can be sure that a majority of the readers will think there was a murder. But we never say that. Never. And we'll never say that it's a murder. Some of the readers may be disappointed by the end because there is no explanation. All we will say is that there is a corpse in the forest. Is she real or is she not is a question? Is there a link between that girl and the man in the forest? It's a good question but there is no answer.

I don't want to compare myself to him, but Terrence Malick's "The Thin Red Line" was a real model for me. Look at that. "You don't give a damn shit about us but we can have a war in a beautiful forest and life will go on and we'll die." [Laughs] That's a strange paradox that interested us.

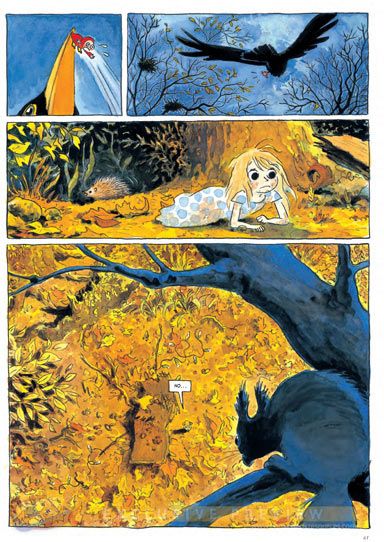

She's obviously not a superhero but is Aurora a hero?

What I learned being a classical writer was, in general, to make the protagonist sweet and kind and good enough to let the reader have empathy for him or her so that he or she can become the hero. Here, it has been very, very hard to do that because Marie didn't want the reader to have too much empathy with Aurora because she wanted to keep Aurora a part of the mystery. We don't always know the motivation of that little character. In a way, she is a little flat. That is to say, she has no color or taste or the taste is very subtle. Aurora is like this.

In the story, she is too naïve sometimes to let the reader like her. At the end of the story, she proves that she's stronger than we expected. She is a protagonist but it is hard for her to create empathy for the readers.

For me, that was the main difficulty for the writing of that story. I felt quite comfortable with no key at the end to explain why there was a body in the forest, but it was harder for me to accept that the readers wouldn't like the hero. It was a choice from Marie and as it was more her story than mine, I accepted it. I think that it's more difficult for the readers to feel at ease in the story and God knows that it is not an easy story to read sometimes. I would have liked sometimes that Aurora could be a real hero and she's not. She is very sweet but sometimes so sweet that it's disgusting and not very loveable.

For readers not familiar with your writing, they have likely heard of Franco-Belgian comics or bande dessinee like "The Adventures of Tintin" and "Asterix." You have written the last three volumes of "Spirou and Fantasio," another long-standing Franco-Belgian series, which debuted in 1938. Are you still writing those?

Yes, I just signed a contract with Dupuis Publishing to write the next five or six albums of "Spirou and Fantasio."

My other ongoing series is "Seuls" or "Alone," the story of five kids that happen to be alone in a big city and we don't know why. This one is about to be translated in English by Cinebook. That's my main success here in France.

But my main, main project that I am working on now is a digital magazine for digital comics. It's called "Professor Cyclops." It's a huge project for me and my friends that work on it because I am pretty sure that the comic book industry is going to change a lot and digital comics are going to evolve too.

One of my main projects belongs to that magazine that we have created one year ago and it's going to be called "The Last Atlas." It's the story of giant robots in futuristic France and we're telling that story as an infinite comic, which doesn't mean that it will have no end but it's told with a specific language that you can read on a screen. In a way, it's like reading panel by panel but it's more than that. It's more subtle. It begins this summer and I hope it's a great serial because I worked like hell on it. It's for adults. We would like to do for giant robot stories what "Game of Thrones" did for heroic fantasy. It has lots of politics and strong links, for example, to immigration in France in the seventies.

"Beautiful Darkness," by Fabien Vehlmann and Kerascoët, is available now.