Today, we look at the 1971 introduction of the Valkyrie in a sociopolitical satire involving, of all people, the Hulk!

This is "Look Back," where every four weeks of a month, I will spotlight a single issue of a comic book that came out in the past and talk about that issue (often in terms of a larger scale, like the series overall, etc.). Each spotlight will be a look at a comic book from a different year that came out the same month X amount of years ago. The first spotlight of the month looks at a book that came out this month ten years ago. The second spotlight looks at a book that came out this month 25 years ago. The third spotlight looks at a book that came out this month 50 years ago. The fourth spotlight looks at a book that came out this month 75 years ago. The occasional fifth week (we look at weeks broadly, so if a month has either five Sundays or five Saturdays, it counts as having a fifth week) looks at books from 20/30/40/60/70/80 years ago.

We're a bit behind, so we're still looking at May books, specifically May 1971's introduction of the Valkyrie in Incredible Hulk #142 (by Roy Thomas, Herb Trimpe and John Severin), which occurred in a surprising sociopolitical satire!

First off, let's note that the Valkyrie sort of kind of made her debut at the end of 1970 in Avengers #83 (by Roy Thomas, John Buscema and Tom Palmer), but that was the Enchantress in disguise. This is the first time that the Valkyrie is introduced as a distinct being and not just the Enchantress using a disguise.

Okay, so let's set the scene for this issue by talking a little bit about the late, great Tom Wolfe, echoing something I wrote about Wolfe when he passed away a few years ago. Wolfe was famous for helping to popularize so-called "New Journalism" in the 1960s (something that Wolfe himself referred to as "literary journalism." The idea was to bring different literary techniques to feature journalism writing that were not normally present in journalism writing. Besides the literary techniques, one of the most notable aspects of this new style was to insert the author his or herself into the feature and to have their viewpoints on the story reflect on how the subjects of the story are depicted. For instance, a typical feature journalist before Wolfe's era would report the "facts" of a situation (quotes because obviously it is always debatable as to whether the facts are ever truly recorded, as everyone sees things from their own perspective - something that played a part in Wolfe's theories on journalism) and the writer would be "invisible" within the article. It would just be a recitation of the events.

With Wolfe, and other "New Journalists" like Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer and Joan Didion, the story would be about their own journey within the story itself. Thus, you would see the story through Wolfe's eyes and you would experience what Wolfe experienced, rather than a theoretical neutral set of "facts" of what happened. When the writer was as witty and as engaging as Wolfe, the story really resonated and stood out from "normal" features, which seemed bland in comparison.

One of Wolfe's most famous books was, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which told the story of Wolfe traveling the country along with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, who rode around in a colorfully painted school bus and embraced the pursuit of LSD as a new avenue to enlightenment. At one point in the book, Ken Kesey was engrossed in an issue of Doctor Strange (Doctor Strange became a bit of a symbol of LSD back in the 1960s). The writer of Doctor Strange, Roy Thomas, decided to then throw in a reference to Tom Wolfe in an actual issue of Doctor Strange, showing Wolfe as an old friend of Stephen Strange in 1969's Doctor Strange #180 (art by Gene Colan and Tom Palmer) and after a positive response from Wolfe, Thomas then went farther and sort of adapted another famous Wolfe story, “These Radical Chic Evenings” a story of a party Leonard Bernstein threw at his New York Park Avenue apartment for his rich, liberal friends who wished to support the Black Panther party. In the article, Wolfe satirizes these rich white people as the “radical chic,” people who are supporting causes like the Black Panther party more for social status than for actual interest in the cause. For instance, Wolfe notes that for the party, Bernstein made sure that there would only be white South American servers for the party. Whether it was a fair depiction of the party or not, it was a very popular satirical piece.

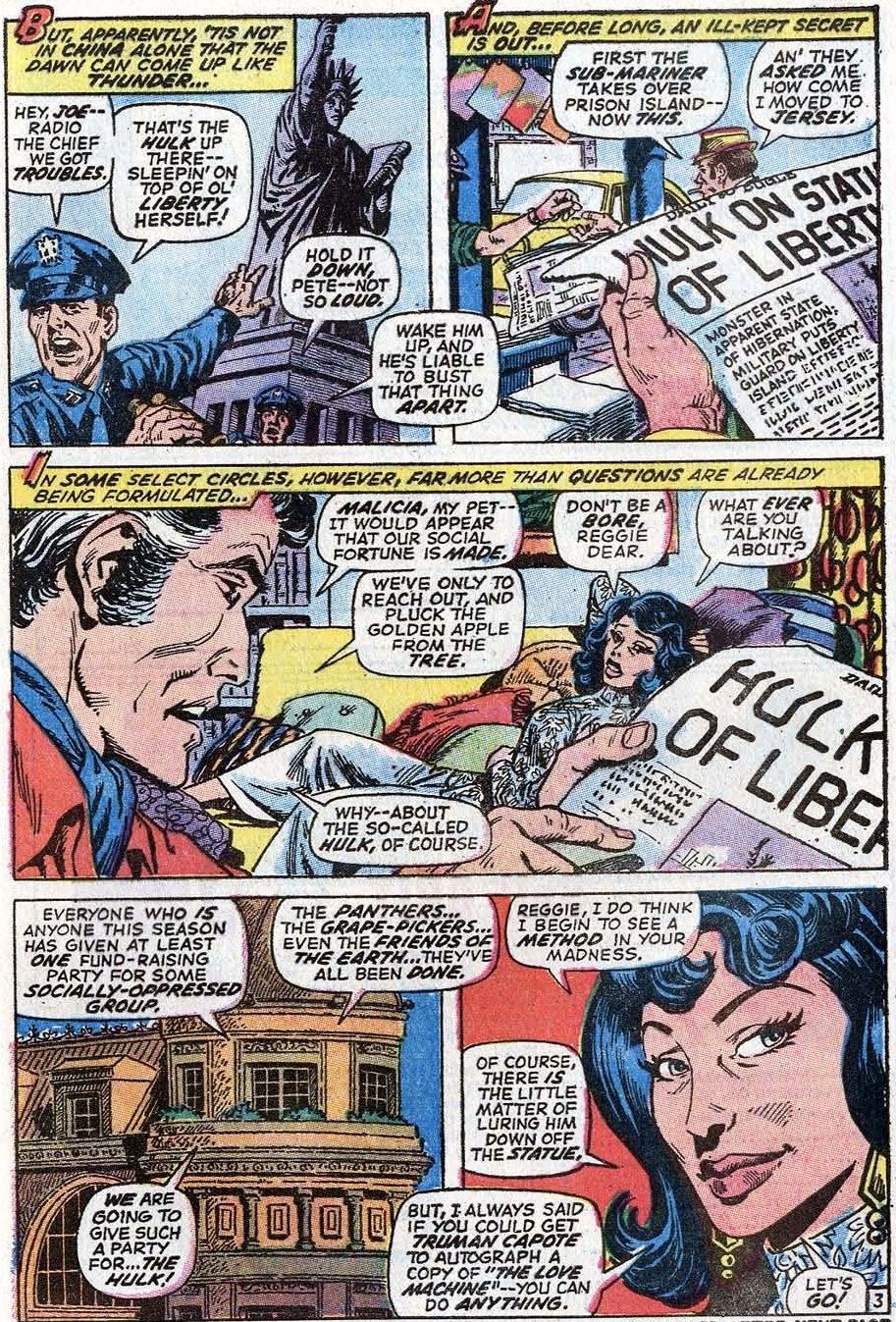

In Incredible Hulk #142 (by Thomas and artist Herb Trimpe), the concept is that a rich family decide to throw a party to raise money for the Hulk, feeling as though supporting the rampaging creature was the most radical of parties that they could throw.

Their daughter is upset, since she wanted her parents to throw a women's liberation party, but since one of their friends had already done one recently, it wasn't chic enough. They also took credit for how it was she who calmed the Hulk down and got him to agree to come to the party. So she and her friends protested the event (Tom Wolfe is there, wearing his famous white suit)...

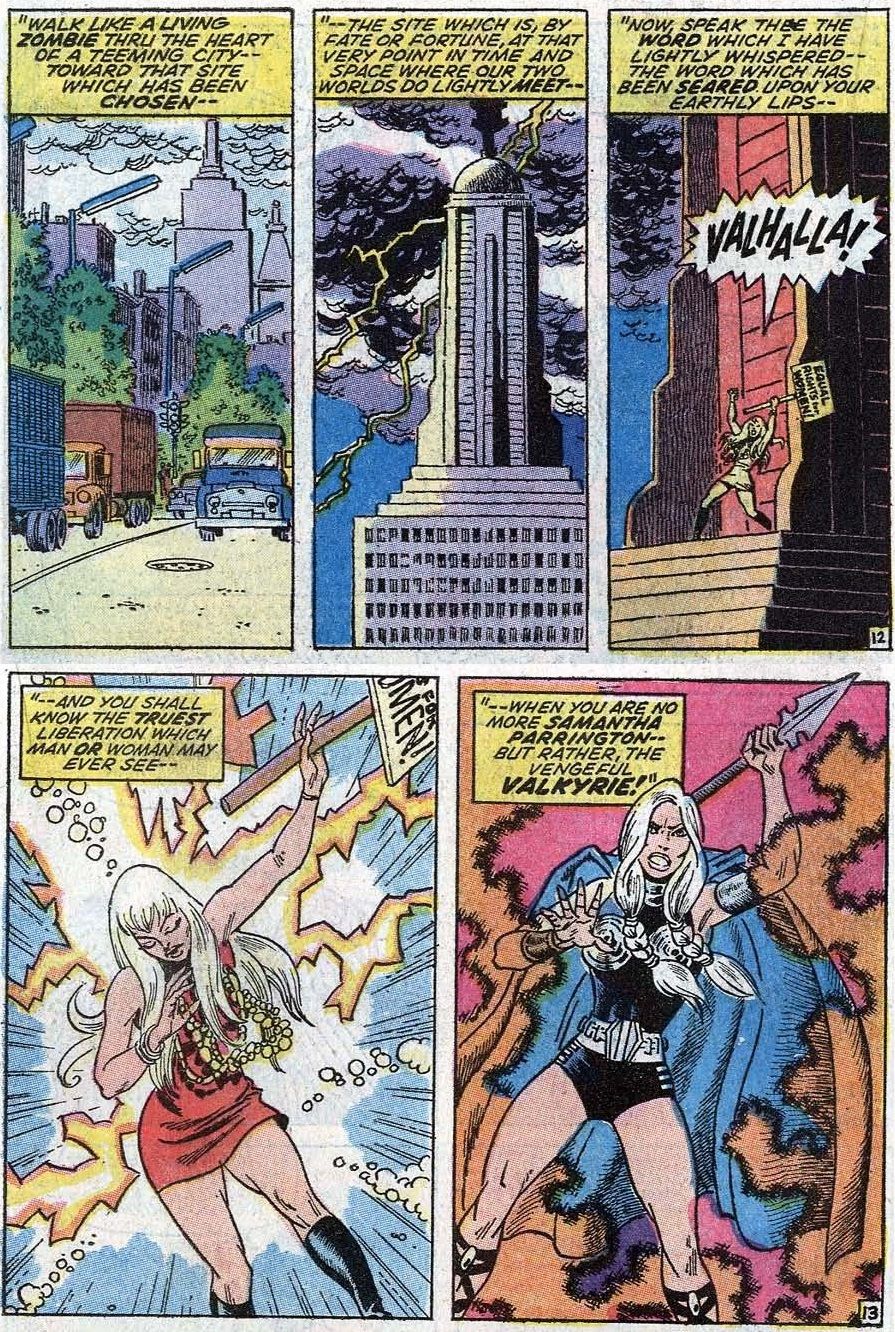

The Enchantress transformed the daughter temporarily into the super-powered Valkyrie (she transforms in the New York neighborhood of Valhalla, of course) and she crashed the party.

Valkyrie is being manipulated by the Enchantress, and it leads to her seemingly throwing the Hulk to his doom from the top of a building (but luckily, the Hulk is stronger than that). The young woman, Samatha Parrington, who was transformed into the Valkyrie, then tries to fight the control and Enchantress just removes the spell and Samantha is left with Bruce Banner, neither knowing how they got there...

The Valkyrie would later join the Defenders in a whole different setup (which I'll discuss some day). In Thor: Ragnarok, Valkyrie is dubbed "Scrapper #142" in honor of this comic book.

If you folks have any suggestions for August (or any other later months) 2011, 1996, 1971 and 1946 comic books for me to spotlight, drop me a line at brianc@cbr.com! Here is the guide, though, for the cover dates of books so that you can make suggestions for books that actually came out in the correct month. Generally speaking, the traditional amount of time between the cover date and the release date of a comic book throughout most of comic history has been two months (it was three months at times, but not during the times we're discussing here). So the comic books will have a cover date that is two months ahead of the actual release date (so October for a book that came out in August). Obviously, it is easier to tell when a book from 10 years ago was released, since there was internet coverage of books back then.