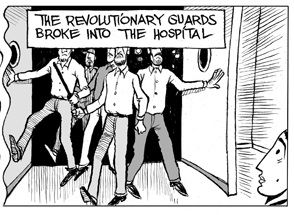

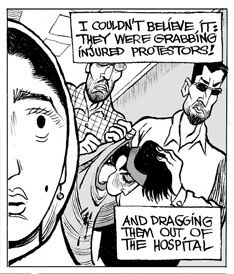

Zahra's Paradise, which debuted on the First Second website last month, tells a story that is at once universal and very particular: A mother searches for her missing son in the aftermath of the protests following the Iranian presidential election of 2009. The creators have chosen to remain anonymous for their own safety, and the comic pulls no punches in its depiction of the brutal treatment of protestors by the Iranian militia.

First Second Books is publishing the story as a webcomic in seven languages, including English, Persian, and Arabic, and will publish it as a print comic next year. With the help of First Second's Gina Gagliano, I interviewed Amir, the writer, and Mark Siegel, First Second's editorial director, via e-mail to find out a bit more about the background and the future of this remarkable graphic narrative.

Brigid: What were your inspirations for this story? Were there particular people or incidents that sparked it?

Amir: The inspirations for the story are many. There’s context and culture. I’m deeply touched by the dreams of Iranian youth, by the nobility of Iranian women, the courage of the Iranian people. In one way or another, their stories of trauma and triumph, joy and genius, are woven into the fabric of my being.

When the revolution of 1979 happened, I was a kid. I saw a lot of people, on all sides, get hurt. And the violence seemed so senseless and unnecessary, and its consequences, the trauma, so vulgar and grotesque. So, I’ve known, since then, that one day I will do something about this nonsense. And that day seems to have finally come. After thirty years!!

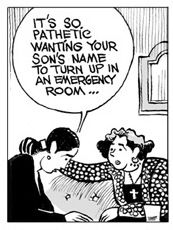

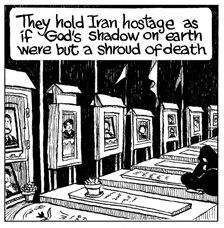

In terms of immediate inspiration, there’s no way I was going to let the dreams of another generation of Iranian youth get shattered in the streets of Tehran. And there was no way I was going to let their memory get wiped out. That meant reconstructing their story—capturing and reflecting their image in some kind of mirror that could store and release their energy, their light. To me, Neda, Sohrab, Mohsen and others are only dead if we think of them and treat them as dead. But, if we don’t, if we tap into their life force, and raise its power by connecting their story back to the world, there’s no telling what their story can do.

Brigid: What is your view of Iran? Did you grow up there? Would you go back?

Amir: Most of my life, I have lived in between places, so I don’t feel as though I belong to any single place. And to be honest, in a global age, or frankly in any age, I find territorial and tribal notions of identity really primitive, bloody and revolting. So I can’t claim to have an extraordinary or exclusive view of Iran.

The Iran I know is the cradle of the family in which I grew up, mostly the love and touch of my grandmothers, a sense of abundance and joy, mixed with the smell of my grandfather’s old books. It was a very simple, stable and secure world that nothing could really shake or destroy, and it has remained a source of energy and inspiration that makes me feel great, happy, lucky and very very rich.

I don’t feel that I need to go back to Iran to find Iran. Iran’s always been around me, and it’s certainly present inside my imagination. I can tap into it whenever I want. Imagination is the best place to hide, find and discover the worlds we love.

Remember, I was kicked out of Iran when I was twelve, flung outside into a much bigger world, and this bigger world has been an incredible sanctuary. So many people around the world from Turkey and Pakistan to France and Germany to Australia and America have opened their hearts and homes to us Iranians—despite all the nonsense about Iranians as terrorists and fundamentalists—that there’s no way I can just live in a bubble called Iran. I’d find that awfully boring and very lonely.

Brigid: Were you in Iran during the presidential elections and the aftermath? How did you get information about what was going on?

Amir: No I was not in Iran during the elections. I got my information from multiple sources — Youtube, bloggers, activists and more.

Brigid: What is at the heart of the comic—what is the story you feel compelled to tell, even though it may put you at personal risk?

Amir: If I may, I will answer this question about risk using an analogy.

I spent years studying history and human rights, and then, after dropping out of university, I accidentally ended up working as a supply chain manager in a lemonade factory. I don’t wish that job on anybody but it was worth ten college degrees. I had to learn everything about the journey of a can of lemonade through the factory into the belly of the city. It’s really mundane stuff—from purchasing to marketing, accounting to shipping. How all these departments relate to each other as the team standing behind the can of lemonade is what would make the factory turn. It all got reduced into a simple equation—could we back the price of our claim and deliver on the promise of lemonade or not.

The heart of the system, as it turns out, was customer service—that’s where we’d interact with our clients and get complaints about defects. If for whatever reason you can of lemonade had a defect, you had to spot the can immediately, pull it out of circulation, and trace the defect to its source.

Now, for obvious reasons, nobody wants to hear that their lemonade sucks—that a bottle exploded in some fridge, or there was hairy guck inside the bottle or that some little girl turned orange drinking it. It’s so much trouble figuring out what went wrong with the can of lemonade. Nobody wants to accept the blame for what’s gone wrong. So, everyone starts hiding and hedging. Was it purchasing that bought bad bottles and lemons, was it quality control that used old lemons, was it production that had hired a hairy employee or was it maintenance that had used to much soap to rinse the lemon juicer? The risk of finding out the truth is too great, so much better to draw a veil over the complaints and get along in obscurity. Who, after all, wants to risk their department’s relations with production or purchasing, sales or shipping by identifying the defect? And if the problem gets to the CEO, then who wants to accept the personal risk of admitting to a fault when their budget, job, honor, mortgage is on the line. But what’s rational at the individual or departmental level is disastrous. You can end up with a city poisoned with a river of bad lemonade spewing out of your factory. The price of your name and brand collapses, the price of your promise erodes, your costs rise, and, sooner or later, you either have to shut down the factory or save it by firing its bankrupt and useless guardians—idiots who don’t know a thing about making or keeping a promise, let alone running a lemonade factory by respecting its promises to each and every single client.

So, to answer your question, by analogy, what compels me to write this story is that the Iranian people are being sold very poisonous lemonade. And the story I’m telling—the story of a single family moving through the belly of the Islamic Republic—allows me to expose processes and attitudes that make failure on such a grand scale possible. Imagine a lemonade factory that poisons its clients and then, instead of adjusting its operations by admitting fault, blames the clients by calling the lemonade “Islamic” because it bears the name and seal of the CEO. And then imagine the factory arresting and murdering its own department heads, as well as the clients, for insulting the CEO by questioning his right to sell bad lemonade in the name of the factory’s founder. That’s why so many Iranians are complaining, and why I accept my share of the risk. God has given us a nose and a sense of smell, and that sense of smell is what stands between us and the disgusting lemonade spewing out of Khamenei’s factory. If he can't accept the risk his decisions create for millions of people, he has no business calling himself "Supreme Leader." Grand coward should be enough. No? Ignoring the Iranian people, look at the stress he has placed on Iran's security services and clergy. People like him are frauds—they cheapen everything and everyone. It's time for him to drink his own lemonade.

Brigid: The elections and their immediate aftermath are over, but the opposition continues. How do you deal with that open-endedness? If something dramatic were to happen, would you revise the story to incorporate it?

Amir: Yes: I’ve been able to weave some events into the story, and I expect we can do more of the same. There’s also the blog aspect of the story, and that allows many other voices and stories to get incorporated in the story. That’s where Mark’s genius, his vision as an editor, kicks in.

Brigid: Many readers, especially American readers, have strong preconceptions about Iran and Islam. You refer to this briefly in your introduction when you point out that "Allahu Akbar" is "not the scream of the terrorist, but the Iranian people's freedom song." How does that affect your writing? Are there things you steer clear of for fear of misunderstanding?

Amir: No, I’m not afraid of the American people’s preconceptions or misunderstandings about Iran or Islam. And frankly, I’m not sure if I’m not without my preconceptions and misunderstandings about Iran and Islam, or for that matter, America. So, it’s a chance for us to learn, if from nothing else, then from each other’s mistakes. And the other side of it is that perception and perspective can open our ideas about space and time, and so a good story can expand our sense of boundaries, identity and the world, and we can only do that together. I think where the intentions are right, and where there is compassion, there’s room for growth…

Interview with Mark Siegel, editorial director of First Second

Brigid: How did this property come to you, and how did you know it was right for First Second?

Mark: Amir and I had been talking for some time, and various proposals were on the table for a project about Iran, but nothing quite seemed right for First Second. Then in June the events in Iran took a dramatic turn, our conversation sobered in some ways, and the next thing was Amir presented this project to me. And it was immediately obvious: this one was born of need. I couldn’t pass.

First Second, from its very first season in 2006, has always included a theme of world affairs, topical, human race issues. Deogratias was one, about the genocide in Rwanda, The Photographer was another, about Doctors Without Borders in Afghanistan. There are more in the works, some of them heavy, some of them lighter in tone. Zahra's Paradise felt right away like a major addition to this collection.

Brigid: Why are you making this available in so many different languages?

Mark: We knew we wanted the Persian version alongside the English, for an Iranian audience in Iran as well as around the world. Soon after that, Amir and Khalil realized that they were creating this for many kinds of readers, including the broad Arabic speaking audience, so we added that. But then several major foreign publishers responded immediately—great houses like Casterman in France, Rizzoli-Lizard in Italy, Norma in Spain, and now Darun in Korea, and more in talks… So naturally, I think the project is contagious, and important, and this reflects it.

The other side of this of course is that more languages means more exposure, right away. And if this can be a small thorn in the side of the Iranian regime, then 10 or more languages makes it an international thorn.

Brigid: How long will the story run?

Mark: As of now it will run at least 160 pages.

Brigid: When will it go to print, and what will the format be?

Mark: 2011 as of our latest plans, but that’s flexible. The web pages may end up being two-thirds of an actual book page.

Brigid: The writer and artist have chosen to remain anonymous. Are you concerned about any possible consequences for yourselves?

Mark: Although it pulls no punches with the Iranian government and its human rights practices, the project is very respectful of Islam and Iran’s religious facets. This isn’t some reckless polemic. What impresses me with Zahra’s Paradise above all is its quality. Its beauty and the depth of its writing make it a work that will last beyond our times, beyond the Iranian regime. Of course, with politics and the Middle East, passions run high everywhere, and opening up any conversation is potentially a tinder box. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a vital thing to do.

The Iranian regime conveniently keeps the focus on the nation’s nuclear program, goading everyone with it to keep the world’s attention away from its cruel crackdown on the opposition. Zahra’s Paradise returns the focus on human rights, and on daily life inside Iran. If anything, where an American audience is concerned, this should humanize our idea of who Iranians are, and help strengthen our connections to each other as human beings. Besides the current political issue, it’s a universal story, a mother’s love for her son, a brother grieving for a missing brother, hope and love in the face of oppression—again, it’s the human story.