Making fun of history has been a good gig for quite a while. I grew up reading Richard Armour’s fractured retellings of history-book standards, such as It All Started with Columbus, and of course Mad Magazine was a reliable source of misinformation. (The Marx/Marx Brothers and Lenin/Lennon confusion lingered for an embarrassingly long time, thanks to them.) And then there is Blackadder, a show whose humor content scales directly with the viewer’s knowledge of British history.

Mock history has proven to be a fertile vein on the web as well. It’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t love Kate Beaton’s Hark, A Vagrant. Reading her irreverent takes on historical topics is sort of like sitting in the back of class drawing moustaches on the Founding Fathers.

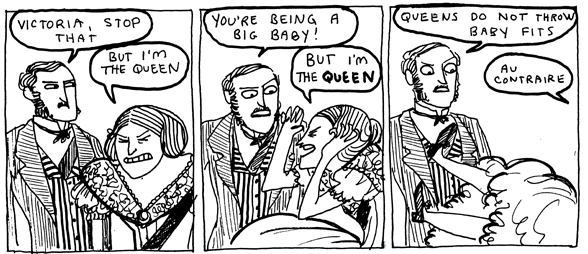

Beaton’s comics are pretty minimalist. Her style is deliberately loose, each comic is a single-page gag, and the gags reliably turn popular concepts of history on their head, mostly showing iconic figures acting in ignoble (but funny!) ways. Her brand of humor, of course, depends on the reader understanding the setup instantly, so she generally sticks with recognizable characters (although we south-of-the-border types appreciate her explanatory notes on Canadian history).

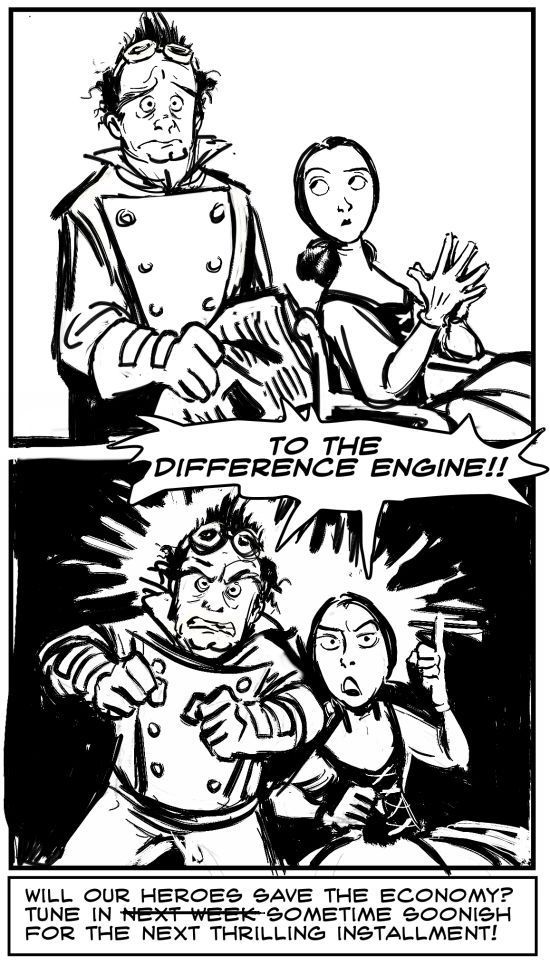

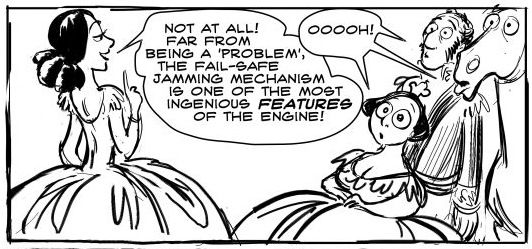

Not so with Sydney Padua; the title characters in her loose series of comics, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, are not household names in most homes. Ada Lovelace was the daughter of the poet Byron and is regarded by historians as the first computer programmer; Charles Babbage designed, but never built, the first programmable computer. Both lived in Victorian times and were quirky but somewhat less exciting than Padua makes them seem in her action-packed steampunk comic.

In Padua's fevered imagination, the pipe-smoking Ada and rather more diffident Charles do build a Difference Machine, a steampunk version of a computer, and they use it to resolve the financial crisis of 1837 and impress Queen Victoria. The comics are funny in an escalating-chaos kind of way with some computer humor on the side that most peopel will get, and Padua’s confident style works well with her complicated subject matter. One of the things I like the best about this comic, though, is her extensive historical notes and her delight in finding new and odd facts about Babbage and Lovelace (who certainly do offer plenty of scope for that sort of thing). I do wish that she would take all this a bit more seriously as a webcomic and introduce such modern conveniences as a “next” button, but I guess I’m happy that someone is doing this at all.

Dylan Meconis’s Bite Me is a vampire comedy set in the French Revolution. I’m already on record as being a fan of Meconis’s more serious historical comic Family Man. Bite Me, is an earlier comic, and although some characters overlap, the feel is totally different—it’s a comedy drawn in a loose, comic-book style. Think rollicking, bawdy 18th-century humor, with vampires thrown in. The story is pretty straightforward: Claire, a serving wench in a French inn, takes a liking to Lucien, a mysterious visitor who sleeps all day—in the wine cellar. When Lucien’s desire for a snack overtakes him, he brings Claire over to the dark side and she leaves her dead-end job to help Lucien and the abrasive Ginevra free their vampire castle from a rapacious noble. The story moves slowly at first, but Meconis tosses in plenty of gags and side trips to keep the readers entertained. The humor is witty and knowingly anachronistic, and like most real historical figures, Meconis’s vivid characters are more interested in their own preoccupations than in the events swirling around them.

Each of these comics is a nudge to the ribs of the educated reader. They puncture the iconic images we were presented with in school, reimagining historical figures as actual human beings and acknowledging that we look back at the past with modern eyes, and therefore with imperfect understanding. At the same time, all three cartoonists clearly enjoy researching their topics and turning up odd bits of historical trivia. That affection for their subject matter, I think, is what sets these comics above your standard gag comic—when you're done laughing, you know a little bit more than you did before, which is more than I can say about any history class I ever took.