Someone pointed out that I should probably just shut it and review Fun Home, so I figured I would. I also recently got Stagger Lee, which is similar in some ways to Alison Bechdel's story and also wildly different. They are both excellent graphic novels, however, so I figured I would look at them together. Because that's just how I roll.

Fun Home is written and drawn by Alison Bechdel and published by Houghton Mifflin. It can be yours for the low low price of $19.95!

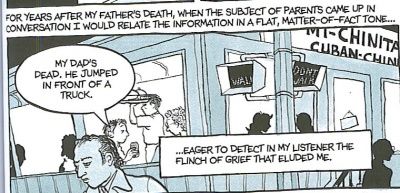

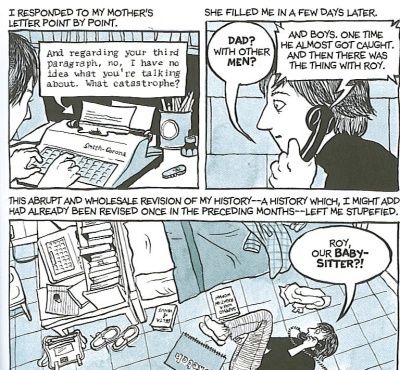

Fun Home is a memoir. It is the story of Alison Bechdel's childhood in the 1960s and 1970s. The centerpiece of the book is her own discovery of herlesbianism, which is followed in short order by her coming out to her parents, her mother's revelation to her that her emotionally aloof father has had affairs with men for years, and her father's death, which may or may not have been a suicide. The entire book is tied into Bechdel's attempts to come to terms with these events and what they mean, as well as trying to come to some sort of understanding of her relationship with her father.

This could easily be a mawkish kind of book, but Bechdel is far too talented for that. She structures the book completely out of chronological order, so that we're always revisiting events and seeing them from a different angle, as she reveals some more information about what we're seeing. It's a wonderful way to read the book, because it's as if we're discovering things as they happen, even though we know they're in the past and we've gone over them before. However, each time we see a scene, we have a slightly different view of it. In a book about people relating to each other, it's a nice way to handle it, and it makes the book move along nicely, where it could have easily bogged down.

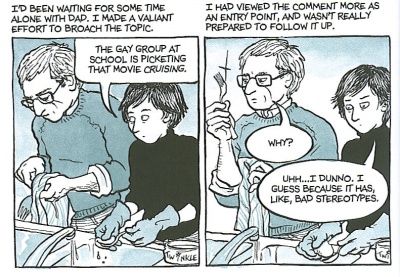

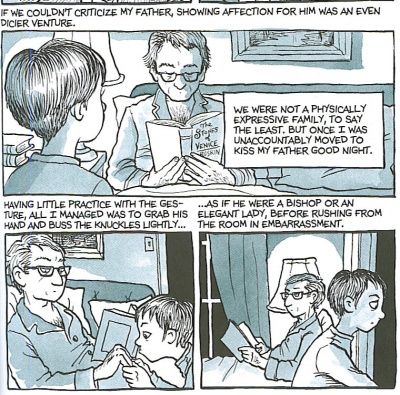

Bechdel writes the book so that her father's death remains central, even though she skips back and forth through time. Every event prior to his death is viewed through the prism of the revelations about him that her mother exposed only a few weeks before his death. She starts by simply telling us about her home life, which is odd and tinged a bit with the knowledge that her father is having affairs with other men (she lets us know this early on), but as she goes back over the details of their early life, we see more and more how she and her father were constantly at odds over her identity - and his. It's fascinating to see how her father is forcing her into gender roles that reinforce his own stereotypes, while she is rebelling against those same roles, all the while not seeing the stereotypes that he falls into. Each one of them is hiding a different person inside them, even if Bechdel herself doesn't know it yet, but neither can express that hidden self, and as we keep revisiting the past, it becomes clearer and clearer that part of the reason why Bruce Bechdel died is because of that lack. We're never quite sure if he committed suicide, but Bechdel implies that her courage to come out of the closet may have shamed him so much that he couldn't go on. This makes her efforts to connect with her father prior to his death all the more tragic, because if only he had lived, the implication is, perhaps they finally could have reached a point where they could be honest with each other. It's this idea that floats through the book that is why Fun Home is such a devastating work. Great writing, after all, leaves as much unsaid as it does said, and that lack at the center of the book is a void that nothing can fill, which is why this is ultimately a tragedy, despite its uplifting ending. There's a beautiful and horribly uncomfortable scene toward the end of the book when Bechdel and her father go to the movies, and while they're driving, Bruce Bechdel opens up just a little about his experiences, and then the moment passes. It's beautiful because, again, of what is left unsaid, but that's what makes it tragic as well. The moment, like so many others, passes, and the two are left apart once again.

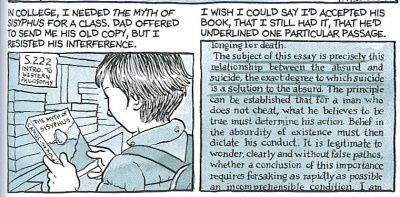

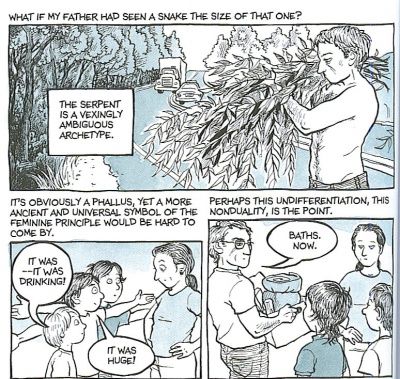

There are problems with the book, and this is why I can't say it's the best graphic novels of the year (although it would be in my top ten, probably). People took me to task for claiming this is "pretentious," which may have been a poor choice of words. Bechdel uses literature as a way to connect with her literary father, and he, in turn, speaks to her through the books he gives her - Collette's autobiography, most notably. There's nothing inherently wrong with using this idea of literature connecting people who can't connect otherwise, it's just that it feels that Bechdel is using it far too much. She quotes whole passages of Joyce and Proust and Camus and Collette, and it feels as if she is using other authors to express what she herself is feeling. In regard to her relationship with her father, I don't have that big a problem with it, but when she is trying to discover what it means for herself to be a lesbian, it feels as if she is trying too hard to study what it means, instead of feeling it for herself. I realize that a lot of college students do this, but that doesn't mean she needs to go over it for us in such great detail. That's what I mean by "pretentious" - not the idea of connecting with her father through others' words, which is actually a very nice way to get across both their issues with communicating, but the overuse of literature to express her own feelings. Look at the myth of Daedalus, which she uses throughout the book. It's not exactly a subtle use of the myth, but it works exceedingly well in the context of what she's trying to do. It links portions of the book, and provides a denouement that is joyous, even though, as I mentioned, the ultimate tone of the book is downbeat. Bechdel uses the myth very well, and I don't think she's being pretentious at all in that regard. In other places, I think she could have dialed back the allusions and everything would have been fine.

The other problem I have with the book is that Bechdel tells us a lot. There is a lot of text in this book, and occasionally she violates the "show, don't tell" rule. Occasionally it seems like she does it for comic effect, and that's okay, but there's a lot here that could be simply shown, and we would get the same idea. In the aforementioned scene with Bechdel and her father in the car, there are six panels after they stop talking in which she narrates what was going on. It doesn't ruin the scene, but I think it would have been more effective if we had simply watched them drive. It would have been more uncomfortable, and we can ascertain what's going on anyway - we've all been there. It just seems like there's too much of explaining how she feels, when we can understand it from the context of the pictures and the dialogue. I don't want a complete lack of narration, but sometimes, it's intrusive.

A final problem I have is that this is an autobiography. I generally don't like autobiographies, and that's my problem, but I try to give them a fair shake, and this one certainly rises above most. But it still tells a story of a rather ... I hesitate to call it unremarkable, because everyone's life is interesting in certain ways ... standard?dare I say - normal life? You might say that a girl who is a lesbian whose father is a closeted homosexual and might have committed suicide doesn't have a normal life, but I mean in the relationship she has with her father. On the one hand, the relationship she has with her father makes the story more relatable, because it's the kind of relationship a lot of people have with their fathers. On the other hand, that begs the question of why we should care. His and her sexual identity is kind of a red herring in this book, which is pretty interesting when you consider how big a deal it is. What's really the issue is that a girl can't have a normal conversation with her father. The reasons might change, but that's not so unusual, is it? I have issues with my father that have never really been cleared up, and I'm not gay and I very much doubt that he is either. He, and Bruce, come from a generation (my dad was born in 1943, seven years after Bechdel's dad) that taught their boys, especially, that opening up and discussing your feelings simply wasn't done. So my father has always had problems relating to his children. Therefore, Bechdel's story doesn't resonate as much as it could, because it's just a story about growing up. We've all been there! Maybe, again, this is my problem. People like to read about growing up and the problems people have, because they can relate. For me, however, it's just not as interesting.

You may think I don't like Fun Home at all. That's not true. I really liked it, and I would recommend it pretty much without reservations to anyone. The skill that Bechdel brings to the telling of the tale is remarkable, and when she does back off on the narration, she lets us see the pain these people are going through and how they simply don't know how to get out of it (Bechdel's mother, with whom she also has a strained relationship, is perhaps the most fascinating character in the book, because of her pain and her inability to deal with it). It's a beautifully understated book at times, and even when Bechdel goes a bit far with explanations, it's still a compelling drama. I'm apparently way off base with my criticisms of the people who loved it, but that doesn't mean I don't think it's a wonderful book. It's a grown-up book for grown-up people. So there's no reason not to check it out!

If you want to buy it, buy it from a cool independent bookstore!

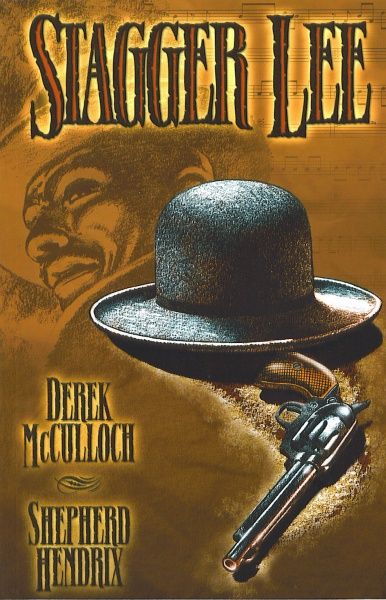

Next up is Stagger Lee, written by Derek McCulloch and illustrated by Shepherd Hendrix. It's published by Image and will set you back $17.99.

Derek McCulloch sent this to me recently, and I appreciate it, because thanks to the opinions of a few bloggers who generally have good taste, I was thinking of tracking it down and getting it anyway. So thanks, Derek - that was very cool of you!

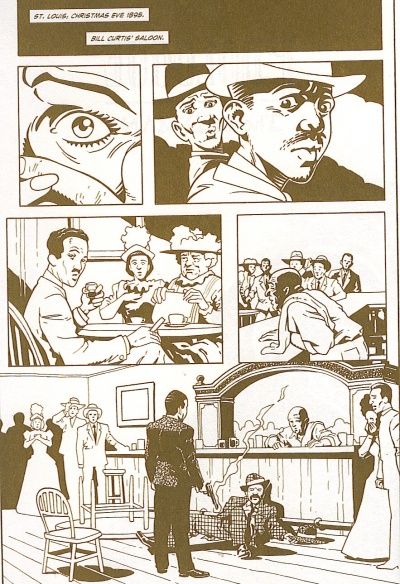

Stagger Lee is a remarkable book, and had I read it a few weeks or months ago, I would have probably included it in my top five graphic novels of the year. McCulloch and Hendrix take the folk legend of Stagger Lee as well as the actual story of Lee Shelton, who shot Billy Lyons in a St. Louis saloon in 1895, and tell a tale of politics, race, and perceptions about people that manages to keep several stories going and always keep our interest. And they keep everything subtle, so that we discern their meanings only through the actions and dialogue of the characters. It's an impressive achievement.

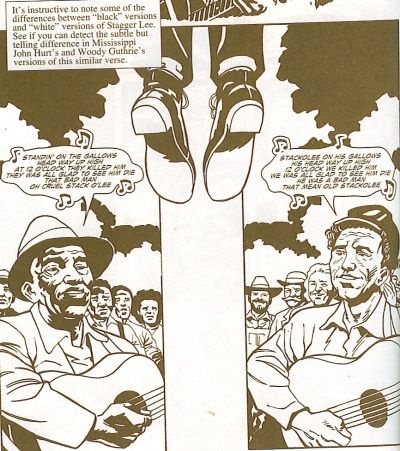

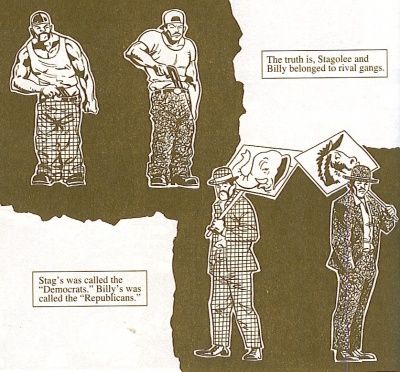

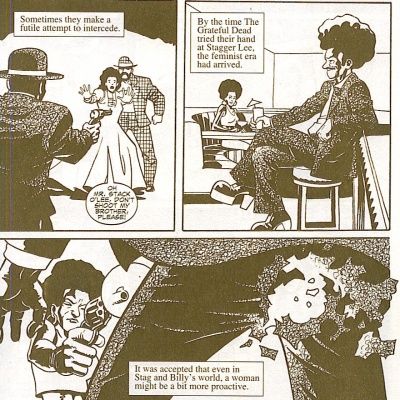

The book is concerned with two things: the actual crime of Lee Shelton shooting a man down in front of several witnesses and seemingly in cold blood, and the legend that springs up around it. McCulloch does this by telling the story of the crime and the trial in a relative straight forward manner. He does use some flashbacks, and the actual shooting is gone over again and again, each time from a new perspective and with fresh information. In this way it's a lot like Fun Home, in that as we learn more about the characters and the events, we can revisit them and reassess what we know about them. Throughout the book McCulloch also tracks the development of the legend through the folk music of the time and how each artist added his or her own layer of meaning to it. Simply by reprinting lyrics of the various versions and telling us when they happened, we can get a brief glimpse into American culture at that time. Although the portions with the folk song become a bit pedantic at times (the only weakness in the book, really), it's still a fascinating trip through the last 100 years of American folklore.

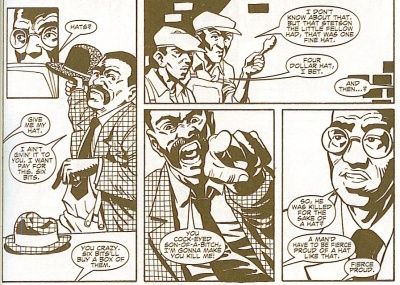

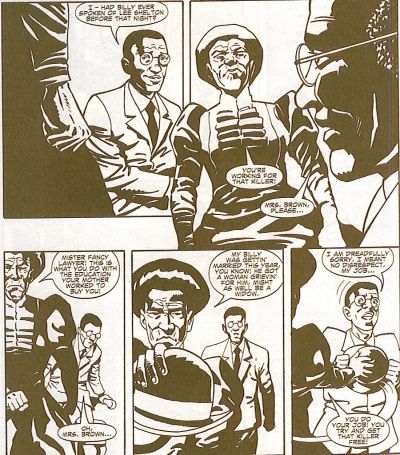

The main story concerns Lee Shelton and his trial. McCulloch throws in a couple of other stories for good measure, all circling racial and sexual politics in 1890s St. Louis. Shelton and Billy Lyons quarrel over a hat (it's a nice hat, to be fair), but the argument is, naturally deeper than that, as Shelton was paid to vote Democrat in an election, and back in those days, blacks voted Republican. Lyons sees Shelton as a traitor. The trial itself is politically charged, as Nathan Dryden, the lawyer who defends Shelton, is asked to take the case by the political boss of St. Louis, "Colonel" Ed Butler. Dryden is the subject of the biggest historical "mistake" in the book, as McCulloch explains in the appendix, but the point is that he's a successful black lawyer who takes the case of an obviously guilty black man, going against another political machine in town, that of Billy Lyons' family. So not only does he go against the prevailing political winds in town, but does he betray his race by taking the case?

We also have the story of Hercules Moffatt and Evelyn Prescott, who carry on a love affair throughout most of the book. Both characters are invented, but their story intersects the main one in an unexpected way. Moffatt plays the piano at one of the whorehouses in town, and Prescott is a lady he meets and thinks is a "high-born" lady, when it's pretty obvious even before we find out that she's a hooker. She keeps telling him that she's engaged, but we don't find out to whom until late in the book (with a few clues planted throughout). She is looking for a way out of the life, and Hercules can't give that to her. She is an interesting character because she once again shows the limitations both women and blacks faced in 1895. All of this, of course, plays out in a highly charged atmosphere, as the trial is dividing the black community, much to the delight of the whites in town, who believe the murder reinforces their stereotypes.

The flashbacks, brief as they are, give us some nice insight into Shelton's character without trying to justify his behavior or even explain it. We can draw our own conclusions about Shelton trying to stand up for himself and forcing someone to respect him at the end of a pistol. The best thing about the book is that McCulloch ties everything together and also ties the themes to the present, where people still act the way Shelton or Moffatt or Prescott or Dryden do, with similar motivations. This is a book that uses the past to illuminate the present, which is always a good thing.

Hendrix's art is stellar, too. Using brown and white, he creates a nice sepia-toned world where everyone is distinctive, so we have no problem telling anyone apart. The sections with the explanation of the folk legend are where he shows off, using wild "camera" angles and hyperbole (when someone gets shot in this section, huge holes open up in the body) to emphasize the legendary aspect of it all. It's very nicely done.

The only problem I have with the main narrative is the flashback to 1890, when Shelton witnessed a murder of a friend. It's difficult to tell exactly what's going on in the scenes, because there is hardly any explanation, and it's unclear why it's included. Later we find out that one of the theories is that he killed Billy Lyons in revenge for that murder, but it's not developed all that much and doesn't make much sense. Luckily, it's introduced quickly and dismissed quickly, so it doesn't distract us too much from the rest of the book.

This is a very entertaining book, and while it entertains, it tries to make good points about where we were as a country in 1895 and where we are now. By using the folk song about Stagger Lee, McCulloch and Hendrix are able to link nineteenth-century St. Louis to the present day and make good points about both times. Stagger Lee is one of the best graphic novels of 2006.

If you're interested, buy it here!

Man, there were a lot of great graphic novels published last year. Very cool. I would rate Stagger Lee higher than Fun Home, but they're certainly both worth your while.