Gødland Finale is a cosmic superhero comic.

There aren’t many of those. It’s a very specific and peculiar sub-genre that entails more than just “happened in space.” Usually, when comics fans talk about cosmic books, they don’t mean this sort of cosmic. They mean “it happens in space.” Which, hey, may be the meaning of cosmic comics now; but it’s wrong. To rip off myself as I struggled to properly define this sub-genre: “Cosmic comics are, above all, the search for enlightenment; the struggle to be more and better.” I wrote those words a few weeks back for something that may or may not see the light of day, but they were words that came back to me as I read Gødland Finale on Wednesday. Not since Marvel: The End have I read a comic that better typifies what a cosmic superhero comic is. A comic where the emphasis is placed on the struggle, not the end result – because, as Gødland Finale shows, the struggle never ends. There is no final enlightenment, no final truth, no place of contentment where one can stop and say, “Okay, I’m done; I am enlightened.” There is a series of endings that are new beginnings, and the journey from each ending/beginning to the next is what matters.

Gødland Finale is the end that argues against an end.

Jumping ahead 100 years from Gødland #36 and its system restore, Joe Casey and Tom Scioli present the next step in human enlightenment. Later in the issue, they jump ahead again “several decades” to show that, after a moment of universal enlightenment and understanding -- another step forward for the human race -- there is still no concrete enlightenment, no final stage. No, there is a promise of more struggle and more growth towards another level of consciousness and awareness. And one wouldn’t be wrong to suspect that it won’t end there. Each moment is one of total clarity and understanding followed by an emptiness, a sense that true meaning was not obtained. Edward Archer is this struggle personified as he, first, eschews the easy ‘assembly line’ version of enlightenment he sees around him, wanting to witness the next step with human eyes and, then, once that step is witnessed, he travels, looking for the next one. In the end, he finds some satisfaction in the journey it seems, realising that the living of life as we try to be more, to reach that next step, is what matters. The journey, not the destination as I heard in a car commercial recently.

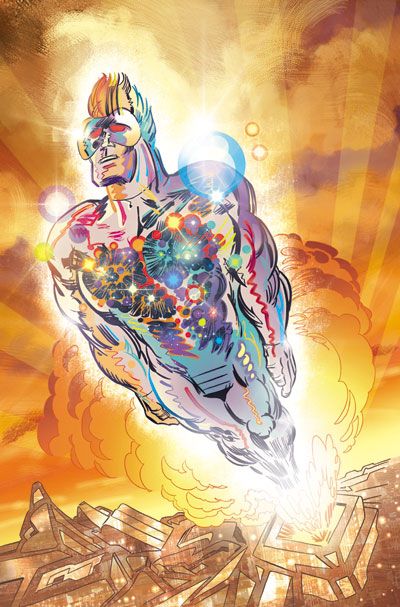

We are to distrust the cosmic enlightenment that begins Gødland Finale. As Edward Archer notes, it’s not what it appears. What he implies is that it’s too easy. People travel to Mars and go through what amounts to a guided tour, becoming cosmically endowed on a moving walkway where they then fly away back to Earth, content to be colourful lights in the sky that pass themselves off as art. It’s not false, but it’s not right either. The former (current?) minions of the Tormentor offer a similar experience in their pay-for-connected-pleasure scheme. Like the Mars enlightenment process, it’s not wrong. There is value in the concept, in the attempt to bring people together in pleasure and lend them a greater connectivity with one another, but the means by which it is achieved are lacking. In one case, it’s enlightenment by assembly line and, in the other, it’s connectivity by pay-per-view. They are cheap, easy methods that are ultimately hollow and incomplete despite having some small part of truth and nobility in them.

Friedrich Nickelhead, as we’ve seen previously, is beyond humanity in the evolution arms race. He already knows the metafictional truth about his existence and reality, having had his eyes opened twice by a butterfly and travelling from one comic to another. However, his role in the comic is vaguer than the others. He has reached a very specific and high level of enlightenment that nearly cripples the cosmic echo that is Atom Archer. He has had his Buddy Baker moment and revels in it. He is content; he is stagnant. He does not struggle for more. Obviously, there are limitations to how far a fictional comic book character can evolve -- even his excursions into the ‘real world’ are still within the confines of a comic. When he visits a comic shop, it’s still drawn by Scioli or Wood. He is the being that has hit the glass ceiling of comic book cosmic enlightenment who can only stick around and look to tease, shepherd, cajole, play with... But, what purpose does he serve? None. In Gødland #36, Iboga told him to create his own reality and he’s done nothing of the sort. He’s become a weird priest of sorts who teaches children and offers sage advice to the Archers and

and

and

and

does nothing.

In a sense, he is the warning of contentment and thinking that the end is the end. When there is no more struggle, what’s left? Friedrich Nickelhead walking through ‘our’ world and talking about meaning where there is none. Where the only point of enlightenment is to be able to say you’re enlightened. Fuck that...

The centrepiece of the issue is the moment of awakening where Atom Archer is launched as the avatar of all humanity, bringing the entire race into the Cøsmic Collective. It should be the crowning achievement of the series, of the race. Finally, there is a moment of true awareness where all is connected, all is known, we are one with the universe and all that that entails. But, it is only for a moment. It is a brief speck that is there and, then, is gone.

“All life is a process. / In the long run, never ending.”

Except for Lucky (and his unwitting victim, Kadeem Hardison) who took steps to take himself out of the path to enlightenment. Thinking that he had outsmarted everyone, he used his grand intellectual knowledge that he mistook for enlightened wisdom and removed himself from the entire equation. What happened next doesn’t even register until the end of Gødland Finale where we see his corpse along with Hardison’s. They never left the room. They stayed there until they died, accomplishing nothing, learning nothing. Just remnants of another time and reality that barely warrant the notice of Edward Archer. Like Nickelhead, they are a warning of sorts.

The comic ends with the promise of further growth, because that’s all there is. Change or die.

A brief interlude to speak about the brilliance of Tom Scioli and other non-Joe Casey people...

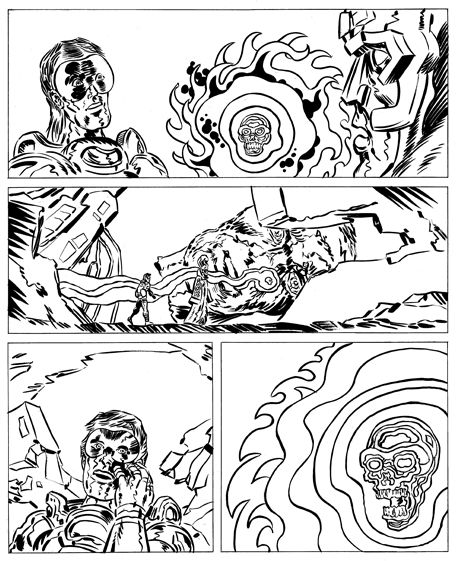

When Gødland began, it was easy for some to dismiss Scioli’s art as a basic Kirby rip-off. Over the course of Gødland (and his non-Gødland works), he’s shown himself to be more versatile and able that such a dismissal would suggest. Nowhere has he proven himself more than in Gødland Finale. Here, he shows his incredible range and ability, offering a variety of styles from the Kirby-esque line work he’s best known for to a similar, more animated/cartoony variation to detailed, warm Atom Archer line work to the fragile, intricate depictions of the departed Lucky and Kadeem Hardison to the glowing video game skull of Basil Cronus to the wild lines of Edward Archer as he struggles to be both himself and part of a greater whole. Each chapter/part has its own distinct look, its own distinct method of delivering information.

It’s easy for me to focus on the parts identifiable as coming from Joe Casey (even though some/many/most/who knows) may have come from Scioli. I think I have an understanding given my extensive experience with Casey’s work, but I don’t want to overlook the influence of Scioli whose visuals define Gødland and its Finale in ways that Casey’s freeform dialogue and cosmic ideals cannot. When I flip through Gødland Finale, Scioli’s art is what hits me first. When I linger over that final part that speaks to me, the way he frames the events -- his use of white space and the layout -- informs its unique place in the comic equally to Casey’s words. And, of course, let us not overlook Brad Simpson, Rus Wooton, and Sonia Harris... I love the colouring on that first panel of the corpse room so much. I love the fade-in lettering. I love a lot about this comic.

Gødland Finale is about Joe Casey working in comics.

Hell, not even Joe Casey specifically, I guess, but it’s easy to pin it all on him, because he wrote the fucking comic, okay? When I look at Gødland Finale, I can see his career thus far in superhero comics. I can see many careers. I can see myself, I can see people I know... (And, thus, I begin to take many liberties...)

The Mars enlightenment is corporate superhero comics. It is an assembly line where many eagerly join, thinking that it is the end-all, be-all of comics. They produce works of bright colours, call it art, and live in blissful ignorance. The Tormentor’s minions offer an alternative, but no matter how lofty their words, it’s still cheap thrills at a price. They may not be as colourful, they may be more lurid and ‘adult,’ but, ultimately, they are no different from the superhero comics that their devotees would mock. Call them non-superhero indie comics (or, not-so-indie in the case of some publishers at the front of Previews). Two alternatives, each calling themselves art, each presenting themselves as what comics are.

Edward Archer chooses neither and openly mocks superhero comics. He wants true human experience, a true moment of enlightenment (acceptance of comics as art). When this is achieved through the pale copy of a superhero joining the mainstream (superhero movies), there is no satisfaction. Comics are accepted. They are mainstream! They are not necessarily thought of as just superheroes or just anything. But, he still doesn’t feel happy about it. After all, comics are still comics and even if he loved them, he still has his own prejudices about them. He looks down on the superheroes that so dominate the medium, but isn’t happy with the non-superhero works either. He searches for meaning, but is the main impediment of that meaning.

Friedrich Nickelhead and Basil Cronus are two different perspectives on comics. Nickelhead is the academic, the critic. He finds meaning and subtext in even the most trivial of works. He makes snide remarks about some dumb comics, but then spends his time obsessing over other (arguably) dumb comics. There is a sense of enjoyment in his work. He does love comics, even the stupid superhero ones, but, partly, because he can pick them apart and show their inner workings, their place in the world. Cronus is more of a pure fan who knows it’s all dumb and meaningless, but still gets his kicks off them. He loves comics, but isn’t afraid to read an issue, have a ball, and, then, toss is aside. They’re just comics and that’s a-okay with him. Neither one is right, neither one is wrong.

Lucky and Hardison are the abandoners. Where Edward Archer continues to struggle and search for what (superhero) comics can mean to him, Lucky simply stopped reading. And what did it get him? Nothing. Quitting solves nothing.

In the end, talking with the two fans, Edward Archer realises that it’s okay to embrace superhero comics. That doesn’t mean you’re dumb or childish, it means you can find something in them to enjoy. He can find meaning in them without having to be defined by the meaning of them. He is where Joe Casey is right now in his career: producing superhero comics, but the kind that speak to him, unafraid to use the genre for his own purposes, and accepting that mainstream acceptance isn’t the end-all be-all it was said to be. Hell, maybe enlightenment wasn’t what was needed really. Outside acceptance means dickall when you don’t have self-acceptance, dig?

Gødland Finale is a damn fine comic book. It was the first comic that I read this week. I read it slowly and with immense joy. I have reread it in pieces and have returned to it again and again. It is everything that I waited for.