I don't do these every month, but when I do, they get pretty long! Strap yourself in and get ready!

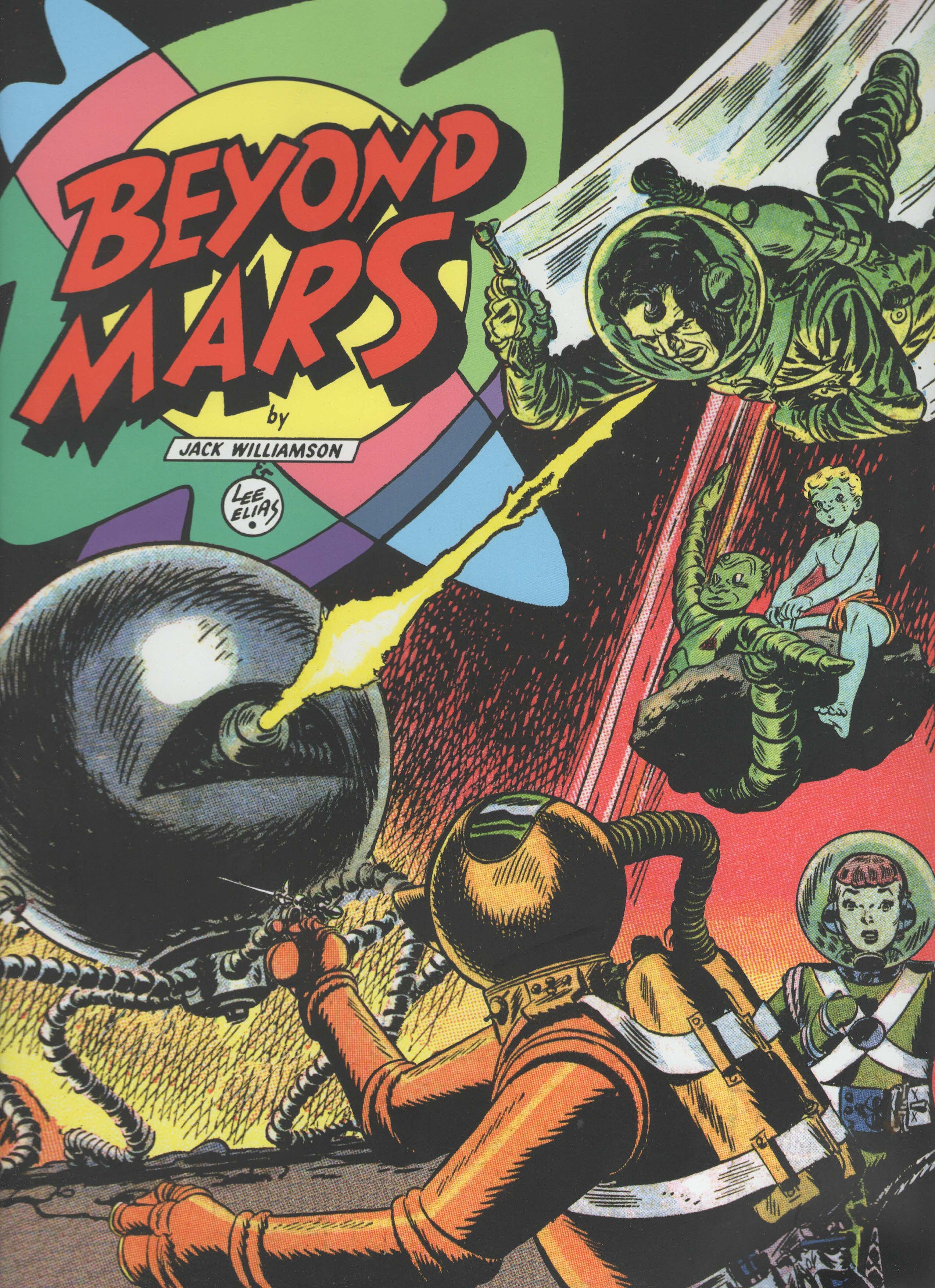

Beyond Mars: The Complete Series 1952-1955 by Lee Elias (artist), Jack Williamson (writer), Lorraine Turner (art restorer), and Dean Mullaney (editor). $49.99, 164 pgs, FC, IDW/The Library of American Comics.

Beyond Mars appeared in only one newspaper, The Sunday News in New York, so if you were a sucker and didn't live in New York in the 1950s (which was the center of the universe, naturally, which is why you never hear about the best centerfielder of his time - Richie Asburn - because he didn't play baseball for one of the three New York teams*), you probably missed it. Williamson was a prominent science fiction writer who wanted a steady paycheck, and Elias was, well, Lee Elias. He was a great artist, and like many artists of the 1940s and 1950s, it's taken 50-60 years for people to realize how good those guys were.

Beyond Mars is kind of bananas, but in such a weird, familiar, Fifties kind of way that it seems less bonkers than it is. We kind of expect Williamson to turn it into an Old West analog - Williamson establishes the premise (which today would have entailed a six-issue prequel mini-series) in a teaser caption before the first strip, in which he explains that a new force - "paragravity" - has allowed men to breathe on asteroids, and so that has become the new frontier of humanity. How does "paragravity" work? Fuck you, just read the strip! Brooklyn Rock, where Mike Flint lives, is an Old West town, down to the saloon and Flint's mother hanging around in her apron making good, wholesome, stick-to-your-ribs victuals for him (he's a tough guy, but he still loves his dear old mama). Much like Old West towns in popular culture, all sorts of people come through Brooklyn Rock, and there's a Snidely Whiplash character (his pencil-thin mustache isn't long enough to twirl, but he does use cigarette holders and he wears an ascot, just like all evil people do), and there's a succession of foxy ladies to distract Mike, all of whom have problems they need the virile, all-American Mike to help solve. In that sense, it's a standard adventure story - if Williamson wasn't influenced by Terry and the Pirates, I'd be surprised - but it's more than that, too. Mike's sidekick is a Venusian named Sam Smith (Tham Thmith, as the alien lisps, which doesn't get annoying at all), who happens to look like a worm and is made out of metal, I guess. Plus, there's the blue-skinned boy wearing a loin cloth who can survive in deep space and rides around on a custom-made asteroid. Oh, and there's the old prospector dude who happens to be fireproof. It's all strange, but Williamson also hints at social issues that he wouldn't be able to address openly - the racist attitude some characters have toward Sam Smith, the imperialist aggression of the United States - and he does it quite well. Even the hero, Mike, isn't as heroic as some others of the time - he's motivated almost solely by money and is far too violent, and Williamson makes sure other characters call him out about that. There's a lot of wackiness in the strip, but Williamson is a good enough writer that he doesn't let it go too far. The comic is very much a product of its time - the women all dress like 1950s women, for instance, and there is a distinct lack of non-white people in the strip - but Williamson does some nice work with it so it's not simply a kooky adventure story, even though there really wouldn't be anything wrong with that.

Speaking of Milton Caniff (and I was, sort of), Elias is definitely channeling Caniff a lot in this strip, but that doesn't matter because if you're going to ape someone, it might as well be Caniff, and Elias is brilliant in his own right, so the art on the strip is amazing. Elias does amazing work with eyebrows, as character arch them and furrow them and raise them wonderfully, giving them a full range of emotions. His characters look like actors from 1950s movies, of course, so Flint is square-jawed and manly, Frosty Karth (of course the bad guy's name is Frosty) is vaguely European (if there's one thing Americans can't trust, it's Europe!), and the women - even the evil ones - are drop-dead gorgeous, yet even though they're all beautiful, Elias differentiates between the kind of beauty they possess - the schoolmarm (yep, of course there's a schoolmarm) has a refreshing and rural beauty, while Dr. Victoria Snow is more modern, Becky Starke is cosmopolitan, and the Cobra has a white streak in her coal-black hair, which signifies her evil (and her mannish cut probably means she's a lesbian, too). Elias designs some really weird creatures, too, from Sam the Venusian to the tentacled Martian with the multi-colored carapace (the Martian also carries a whip, which is ... strange). His best work might be the way he designs the interiors of the various spaceships - some are luxury cruisers, and Elias definitely makes them look so, while others are salvage ships or exploratory vehicles, and Elias does a fine job with the instruments inside the ships and the claustrophobic aspects of the space inside. Obviously, he only had one page onto which he had to cram quite a lot (which leads to some strange page layouts), but the comic itself never feels cramped, just the parts Elias wants to be. Even when the strip was cut to half the page (which happened on 12 September 1954, about six months before it ended), Williamson was able to write scripts that fit and Elias was able to get everything into the space nicely. Elias was a terrific artist, and it's nice to see all this art of his together between two covers.

This is a bit spendy, but such is life with reprints of 60-year-old comics, especially when we get such a nice package. This is just another example of comics from before the superhero explosion of 1961 that proves how good those creators were. Beyond Mars is a bit goofy, but it's a lot of fun, and it's absolutely beautifully drawn. It's a neat book.

* Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider? FUCK 'EM!!!!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

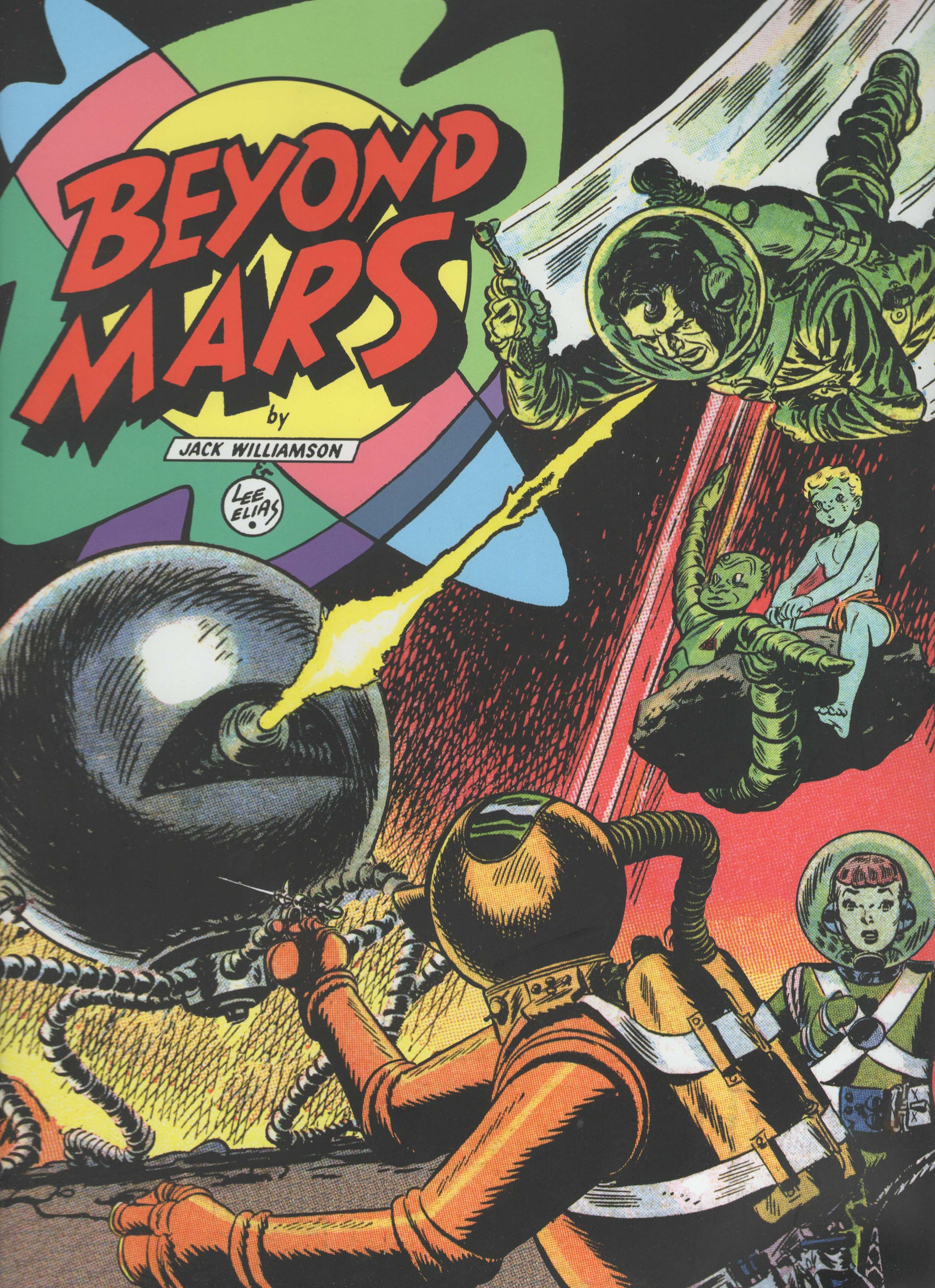

The Complete Adventures of Cholly and Flytrap by Chris Eliopoulos (letterer), Annie Parkhouse (letterer), Arthur Suydam (writer/artist), and John Workman (letterer). $29.99, 255 pgs, FC, Titan Comics.

I'm always curious to see the work of people who are primarily known for, say, covers (as Suydam is), because at some point, they had to do "grunt" work that got them to a position where they could just do covers, right? Suydam is a classic example of that, as he's far more famous today for his "zombie" covers than for any sequential art he may have done, but Cholly and Flytrap is a fairly famous work, so it's not like no one knows that he once did actual comics. These stories have been reprinted over the years, but it's nice to have them all between two covers, and Titan's production values are very good, so the book itself is nice.

Suydam's artwork certainly doesn't disappoint - it's obviously very influenced by Heavy Metal and artists like Moebius, especially the early short stories when he (presumably) had a bit more time. The art is amazingly detailed, giving us a beautiful look at the wasteland through which Cholly (often called "Charlie" in the text) and Flytrap wander. He brings the desert starkly to life and populates it with wonderful characters, including the titular ones, but also giving us humorously-designed characters so the tone is often lighter than you'd expect. The lushness and shading of the early stories gives way to a starker line in "Center City," the main Cholly and Flytrap story, which takes up the bulk of the book. The art is still amazing, but it's a bit more cartoonish, and while Suydam still spots blacks really well, he seems to get more usage out of hatching rather than painting, which might be because of deadlines, but perhaps it was just him experimenting. "Center City" is more satirical, so the art matches the story quite well, and Suydam still does some fascinating things - a few pages are colored in shades of red to show the violence occurring - but it feels more influenced by early Mad magazine artwork and less by the lush and majestic art of the 1970s Europeans. Suydam blends the cartoonish and more realistic violence quite well, so that it feels like a Tom and Jerry or Bugs Bunny cartoon that has gotten completely out of control. His satire works better in the art, too, as he juxtaposes sexual imagery with violent imagery but doesn't call too much attention to it, and his boxing champion - Stanley Yablowski - grows larger throughout the book until he's an unchained monster, destroying the very people who turned him into a champ but don't see him as a human being. Suydam makes some missteps in the art - the robots in Center City, who are agitating for equal rights and are Suydam's stand-in for black people, are a bit too stereotypically "black" (yes, even though they're robots), and it undercuts Suydam's attempts to make a social commentary as well as an action comic. The racial coding - there are absolutely no actual black humans in this book - is unfortunate and unnecessary (and not limited to blacks; the main villain in "Center City" is a horribly stereotypical Jew who lusts after an alabaster white boy - although the character constantly tries to tell the villain that she's a girl), and it mars what is otherwise a terrifically drawn comic. I don't get why artists in the 1940s would draw such offensive stereotypes, although I understand it a bit more, but I really don't get why anyone after the 1960s would do it. It's kind of sad.

As a writer, Suydam is a good artist, amirite? The stories are okay, but nothing great. The short stories are almost non-existent, featuring Cholly and Flytrap coming up against things that want to kill them and killing them in return. "Center City" is an attempt at satire, but like a lot of writers, Suydam never met a point he couldn't beat to death, so he leaves subtlety behind and gives us stereotypes, broad characters and random events that don't really form too much of a narrative. Suydam, like many writers, doesn't really think too much about creating a real world in the future (he doesn't consider that technology might change, for instance), so his world is populated by characters that look like they stepped out of the 1980s, which isn't the worst thing in the world (the book was mostly done in the 1980s, after all), but makes it look very dated. Suydam's ideas about artificial consciousness are far less complex than most sci-fi writers of the era, so even though he does try to make this a socially conscious comic, he doesn't really come close. His parodies of the cult of personality are spot on, but they're spot on because it's easy to parody that, and so we can't give him too much credit. It's an entertaining comic, to a degree, but it's certainly not as good as the art suggests. Like a lot of artists who want to write, Suydam isn't quite as clever as he thinks he is.

Like a lot of old comics that I get these days, I'm glad I own this even if it leaves something to be desired. Suydam's covers are distinctive and even iconic (whether you like them or not is up to you), but I was always curious if he knew what he was doing when it came to creating an actual comic. His storytelling is perfectly fine - very strong in many instances - and the art is wonderful, but the writing just isn't up to snuff. Still, it's kind of fun to have all of these stories in one, nice book.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

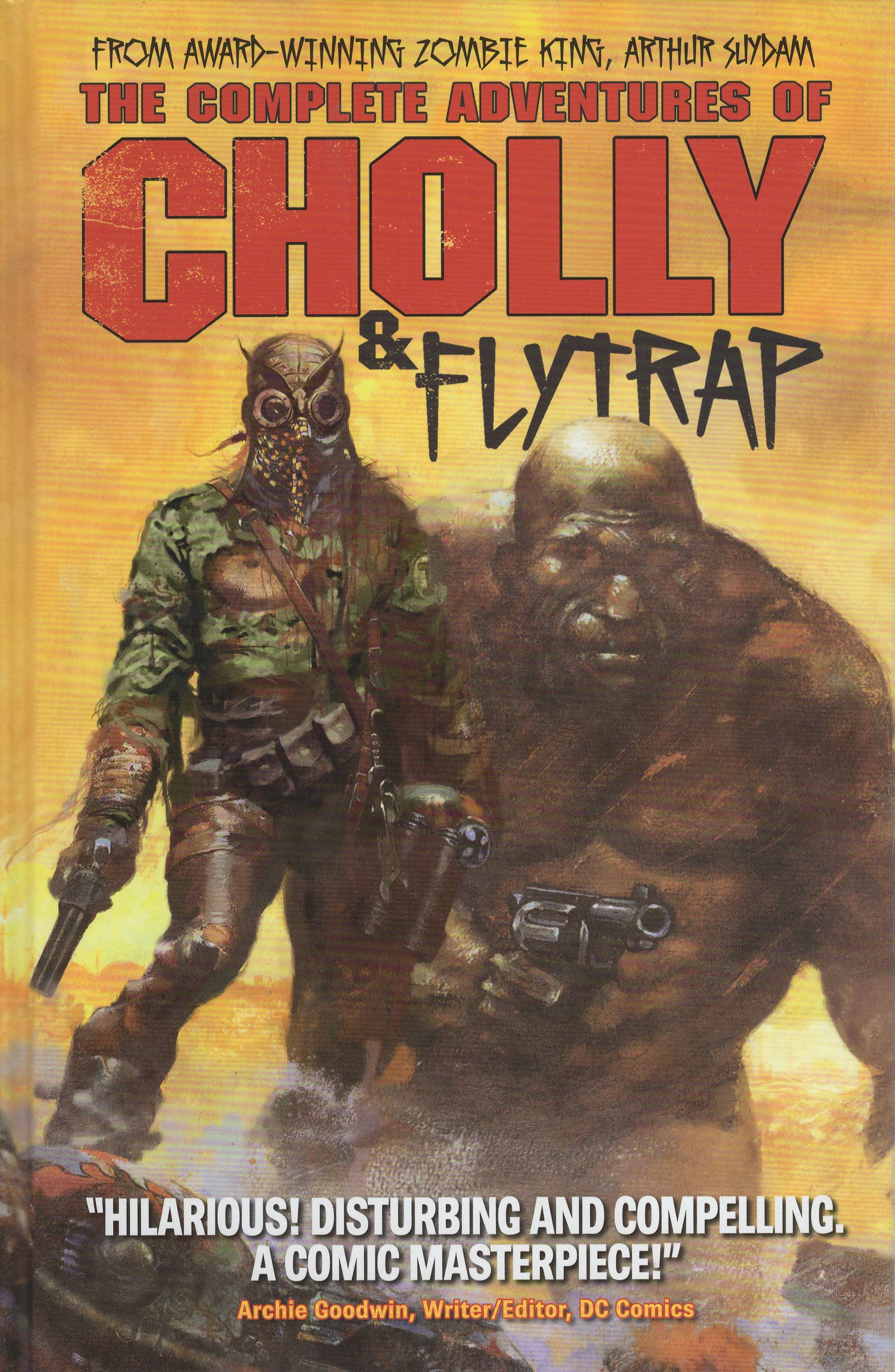

Ivar, Timewalker volume 2: Breaking History by Andrew Dalhouse (colorist), Karl Kesel (inker, issue #8), Francis Portela (artist), Dave Sharpe (letterer), Fred van Lente (writer), and Tom Brennan (editor). $14.99, 88 pgs, FC, Valiant.

This is the second volume of Ivar, Timewalker, and it's planned for three, so it's the middle section, which means that van Lente takes the set-up from the first volume, in which Ivar recruits Neela, who was about to invent a time machine and rescues her from a group that wants to kill her. That group turns out to be led by Neela herself, a version from the far, far future, who wants her to finish making the time machine. Ivar recruits his brothers, Gilad and Armstrong (of Archer and Armstrong fame) to stop Future-Neela. It's a time travel story, so it's all very, very confusing (to me, at least). But van Lente has to move the plot along without wrapping anything up (as he'll do that in volume 3), and he does a pretty good job of it. He can't exactly defeat Future-Neela, but he does give Present-Neela, Gilad, and Armstrong a mission going forward. I don't know - there's not much to say about this. Van Lente is a good writer who writes very good dialogue, so the book reads like a particularly good sitcom, even though van Lente is also quite good at giving us weird villains and clever ways out of death traps, so we get those, too. My favorite moment is when Present-Neela solves the time travel problem and she and Future-Neela squee like little girls, because it's such a thing that would happen. I also dig Portela's work - I don't see it that often, because he often draws comics I don't want to read, but I dig it. It's a bit sterile, I agree, because Portela's lines are so thin and crisp, but he's one of those artists who can work well with the digital coloring that Valiant uses, so the art tends to pop nicely. It's strange, because Kesel is such a good inker, but he doesn't work great with Portela, as his inks are just a bit too thick for the pencils and colors. It's still good art, but not as good as when Portela inks himself.

I really enjoy van Lente's output for Valiant - he's done a nice job with that portion of their universe, and I'm looking forward to volume 3. I'm sure it won't be long before it's offered!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

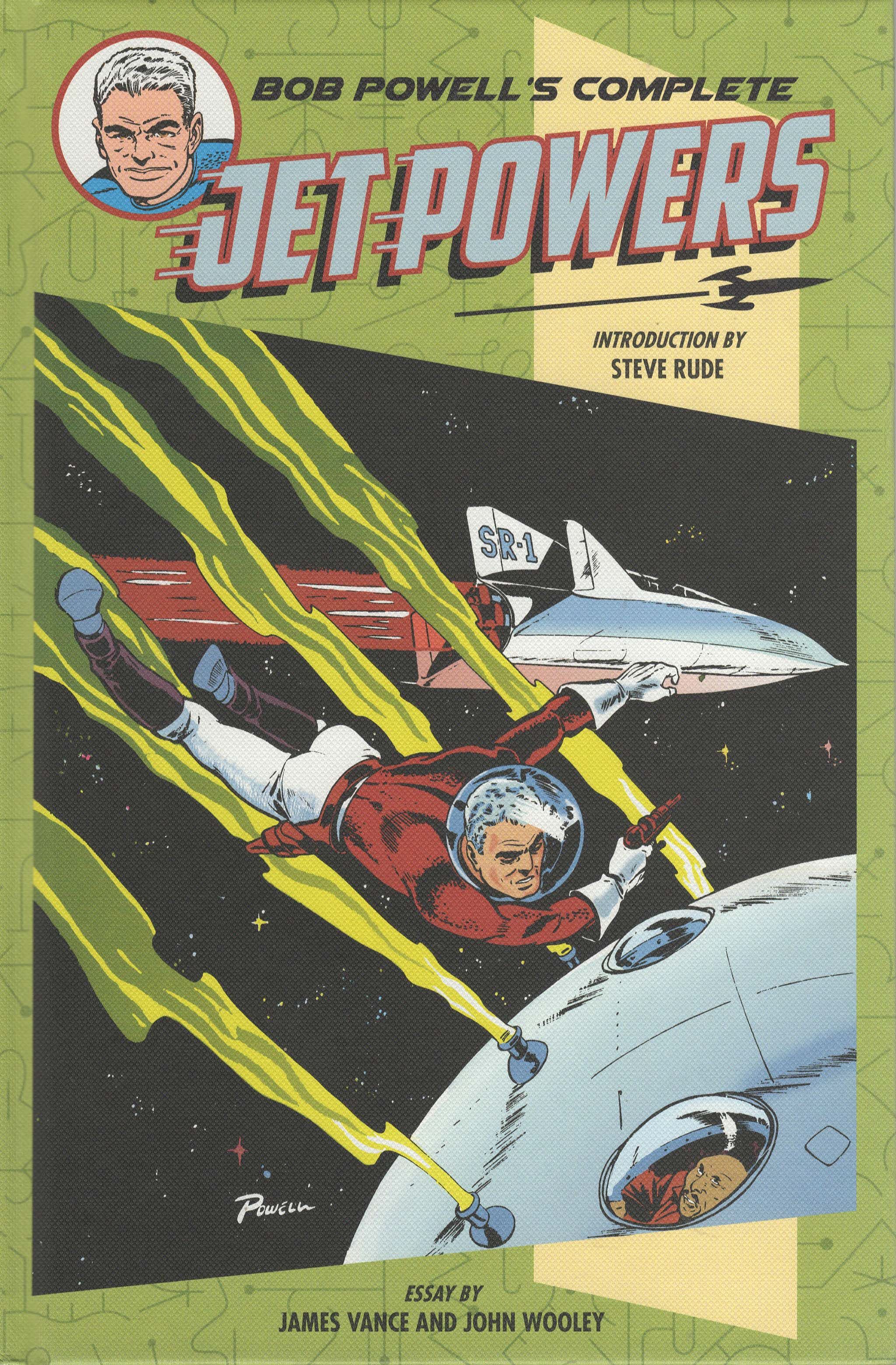

Bob Powell's Complete Jet Powers by Gardner Fox (writer)?, Bob Powell (artist/writer[?]), Ryan Jorgensen (scanner), Ken Cooper (colorist retoucher), John Lind (editor), Denis Kitchen (editor), and Philip Simon (editor). $49.99, 167 pgs, FC, Dark Horse/Kitchen Sink Press.

If you're keeping track, this is the second collection of 1950s comics I bought in this very post. Will there be more? Stay tuned!

I bought this, of course, because of Bob Powell. Like many artists of the 1950s, Powell is woefully unknown, perhaps more than some others as he died in 1967 and never really got involved in the superhero renaissance of that decade. I never knew about Powell until a few years ago, when companies started reprinting his work, and now I'm glad they're doing it, because he's a tremendous artist. His sense of perspective is perhaps what strikes me the most about him - a lot of artists from the 1950s seem to have the knowledge but not the best skills when it comes to placing things in perspective, but Powell fills panels with foreground and background details in perfect relation to each other, giving the artwork a very "modern" look, especially when compared to a lot of the art from that decade (even some great artists - Ditko springs to mind - have some issues with perspective during the 1950s, which in Ditko's case might be because he was so young). Powell is a man of his time - the main villain early in the book, Dr. Sinn, is an awful Asian stereotype, for instance - but we can also see that he is at least trying to push the medium forward, which the best artists of any time tend to do. There are so many small details that make the art come alive - his action, even when confined to small panels as those comics often were, is quite fluid; he uses shading and spot blacks really well, including terrific silhouettes in the most depressing story in the book (the one in which a large percentage of the world's population is killed); and his explosions in the second section of the book, which takes place during the Korean War, are wonderful. Powell was a great horror artist, and he brings some of that to this comic (it was pre-Code, after all) - the violence is fairly gruesome for a standard science fiction comic, and when the book shifts to the war, Powell gives us pilots getting shot to pieces in their cockpits (with all the requisite bloodshed), an evil woman battered and beaten before getting crushed by a statue, and a torturer getting shot right between the eyes. Powell is also quite good at faces - his women, naturally, are sexy as hell, but his men are a bit different than the way they're usually drawn in the 1950s. Powell tends to give them flatter faces with fuller features - including noses and lips - which gives them a kind of fleshy sensuality. Even his hero, Jet Powers, is drawn this way, and it's an unusual way to draw people, especially at this time. Even Jet, who is conspicuously modeled on Jeff Chandler, has a bigger chin and more Roman nose than we might expect from a hero. I get a sense of early Steve Pugh from Powell's artwork, and I wonder if Pugh counts Powell as an influence.

The stories aren't bad, even if they're kind of secondary to the art. Most people think Fox was the main author, although Powell often contributed to the writing, as well. The four issues of Jet Powers (when the hero was still a "science hero" before moving to Korea) are fascinating, in that Fox (or Powell) tells a continuing story. Most comics of the day, of course, were one-and-dones, but in issue #1, we get Dr. Sinn and his Girl Friday, Su Shan, and a diabolical plot to destroy the world's cities. Jet thwarts that, but Sinn returns a few more times, and Su Shan becomes Jet's untrustworthy ally - at least for a little bit, before she realizes that Jet is the bee's knees and Dr. Sinn is, like, totes douchey. There's also the annihilation of a majority of the world's population, which comes about from a strange cosmic event (hey, it's like Night of the Comet!), which, in a later issue, leads to a general and his evil femme fatale trying to take over what's left of the United States. Jet also visits Mars and fights off alien invaders in two separate stories, which are nevertheless linked. It's an interesting and prescient way to tell stories, as of course that became the norm over the course of the next decades. Jet Powers got cancelled, however, and Powell moved over to The American Air Forces (which was also published by Magazine Enterprises), and he decided to repurpose his hero - sporting the same name and looking the same even though it's clearly a different character - for that comic, placing him in Korea. These stories are fairly psychologically complex for the period - in the first one, Jet has to overcome his fear of death before he brings disaster on his fellow soldiers; in another he and another pilot give themselves up as bait for the MiGs of the Chinese, which doesn't necessarily go very well; two ancient Korean gods seem to take sides in the conflict in one story; a soldier believes he's bad luck and wants to quit before Jet gives him new hope in another story. There's a Korean girl who acts as a spy inside North Korea and is (almost) whipped for her betrayal, before Jet rescues her. They're not quite as fascinating as, say, Blazing Combat from the 1960s, but given that this was before Americans had become disillusioned with foreign combat, the stories feel a bit ahead of their time.

If you've never seen Powell's art ... well, you might want to get Bob Powell's Terror, which was published by IDW and Craig Yoe a few years ago, mainly because that seemed to allow Powell some more freedom to be truly odd. But Jet Powers is a cool comic, and it's another example of why Powell was so good. The stories feel a bit more modern than most from the early 1950s (if we make allowances for the racist depictions of Asians, which is a big allowance, I know), and the art is tremendous. We live in the Golden Age of Reprints, so there's no excuse for not knowing Bob Powell!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

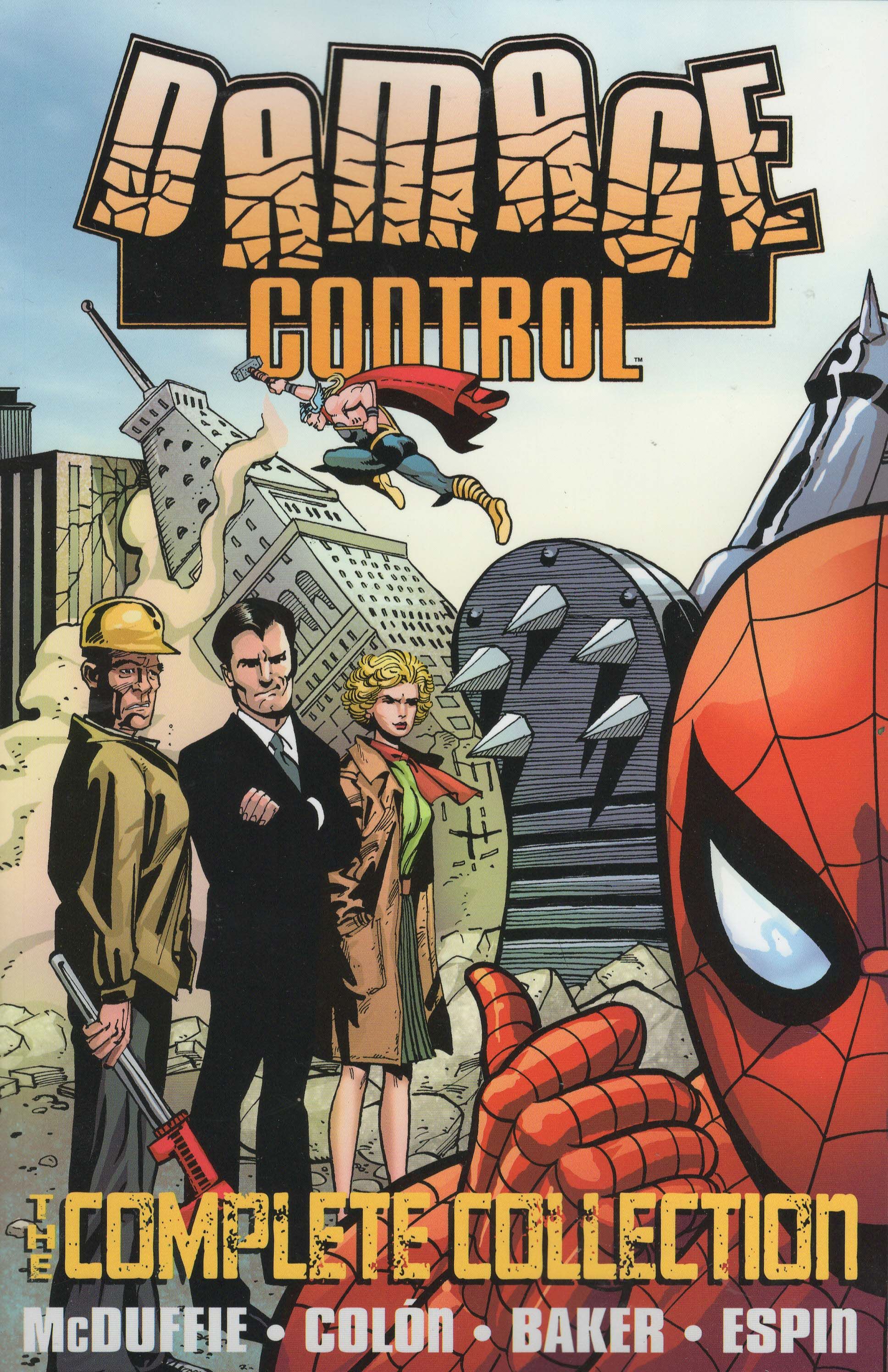

Damage Control: The Complete Collection by Kyle Baker (artist), Robbie Busch (colorist), Ernie Colón (artist), Jon D'Agostino (inker), Stan Drake (inker), Salva Espin (artist), Guru eFX (colorist), Brad K. Joyce (letterer), Ed King (letterer), Dwayne McDuffie (writer), Rick Parker (letterer), Nate Piekos (letterer), George Roussos (colorist), Marie Severin (inker), Brad Vacanta (colorist), John Wellington (colorist), Bob Wiacek (inker), Al Williamson (inker), Gregory Wright (colorist), and Mark D. Beazley (collection editor). $34.99, 392 pgs, FC, Marvel.

I suppose I should point out that this is actually "Dwayne McDuffie's Damage Control" - after the third original mini-series, we get a brief recap of the company's history between that series (which came out in 1991) and the last mini-series (which came out in 2008). The parts of Damage Control's history during Civil War are included in that recap, but they're not reprinted here, probably because Damage Control didn't have a separate series during Civil War but possibly because McDuffie didn't write those sections. It's not too big a deal, however.

Damage Control has always been a stroke of genius, because of course the Marvel Universe would need a company like it, and McDuffie does a fantastic job keeping the tone light throughout the four series, even the "Aftersmash" one that ends the collection. There's not much to say about the stories - McDuffie gives us just enough action to keep it within a good superhero universe framework, but the focus is on the humor, as the executives have to deal with grumpy clients and striking workers, while the workers have to deal with problems about how to actually fix things. The most famous issue, perhaps, is the second one of the original mini-series, in which the company's comptroller goes to the Latverian embassy because Doctor Doom hasn't paid his bill. It's a hilarious story, and indicative of the entire run - it uses the weirdness of the superhero universe very well but doesn't ignore the nut and bolts of making it work. If Kurt Busiek wasn't partially inspired by McDuffie to create Astro City, I'll eat my hat. There are plenty of subplots (Thunderball's friendship with John Porter and McDuffie's portrayal and Thunderball overall is very nice), there's some ridiculous, broad humor but also some very nice subtle commentary on the way things work in the Marvel U., and McDuffie does inject some action into the stories just to keep things hopping. He also accommodates the changes in the characters well, as Speedball plays a role in the original stories, so McDuffie has a nice scene with Penance (yuck) and Bart, the intern/personal assistant whom he befriended, who tries to talk him out of, you know, being Penance (yuck). Those are some nice moments.

The art is bizarre, because the space between the original three series and the final one spans the gap between old-fashioned art and new-wave art, and the differences are striking. Ernie Colón is a fine artist for the book, because his bold, sharp cartooning helps nicely with the comedic tone of the comic. After 15 years, the shift to digital art - both drawing and coloring - is shocking, as Espin is a good comedy artist in his own right, but the digital coloring is too rendered (this was a big problem in the last decade, and while it's gotten better, it's still a problem today) and too dark, so the book looks gloomy even when Damage Control is confronting, say, a sentient Chrysler Building (as they do). The "Aftersmash" story is fun and in the same vein as the original stories, and Espin is a good artist, but the difference in the way the final series looks compared to the ones from the late 1980s/early 1990s is striking.

The idea is still brilliant, however, and it would be nice if we could get a mini-series with the group every other year or so. The fact that it might show up on television could be a great thing, as long as they keep the humor (and why wouldn't they?). This is a nice collection of fun comics. Don't we all need more fun in our lives?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

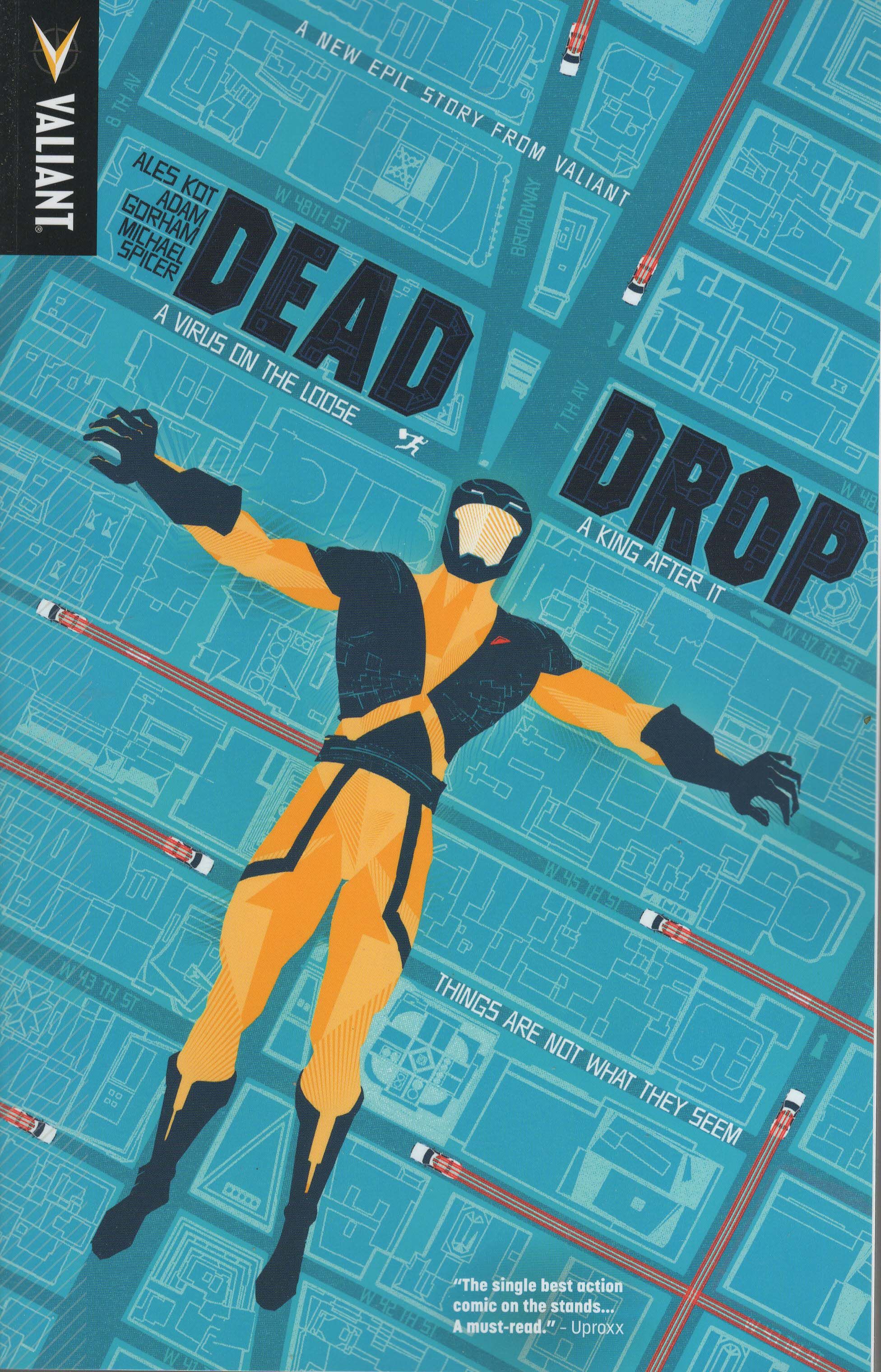

Dead Drop by Adam Gorham (artist), Ales Kot (writer), Dave Sharpe (letterer), Michael Spicer (colorist), Warren Simons (editor), Kyle Andrukiewicz (editor), and Tom Brennan (editor). $9.99, 100 pgs, FC, Valiant.

It appears that Ales Kot might be one of those writers who greatly benefits from an editor. His creator-owned stuff has been up and done (unfortunately, largely down), but he still has good ideas and good skills, things that might be focused more in corporate properties where an editor can tell him things he can't do. We've seen this before - Garth Ennis, I would argue, is a far better writer when someone is looking over his shoulder - and there's nothing really wrong with it, as some writers just can't make a leap to where they can see that not everything that springs from their mind is precious and genius. Dead Drop is a fine idea written and drawn with verve, and Kot is able to cram some weirdness in there without meandering all around wondering what life really means and whether William S. Burroughs created the universe. Kot's idea of a virus that can destroy all humanity isn't new, of course, but he gives it a nice twist so that it's a bit more clever, even though by doing so, he kind of writes himself into a corner (it's never really explained why the people who want to release the virus specifically want to target humanity). He puts another nice twist on it as various Valiant characters - X-O Manowar, Obadiah Archer - chase down the people who stole the virus, but the people who stole the virus have a whole agenda that the "good guys" don't consider. So while X-O Manowar and Archer think they're doing a good thing, they may actually be doing a bad thing unwittingly. So that's kind of neat.

Kot and Gorham keep things humming along - this is a lean four-issue mini-series, and a good deal of it reads like Run Lola Run, as the heroes - Manowar in issue #1, Archer in issue #2 - chase the thieves across New York (we get maps provided to us at the beginning of each issue, handily enough). Gorham does really nice work - his line work is scratchy and frenetic, so we get a good sense of the chase, but he's also quite good at drawing the bad guys, where he needs to slow down and provide more solid details. He does some clever tricks with the panels to show movement well, and his rough art serves him well when Detective Cejuda enters the bad guys' ... lair, I guess. He shifts from a frantic pace to a horror movie setting really well, and makes the insanity of some of Kot's ideas work well in a more grungy setting. Kot comes up with the weirdness, but Gorham makes it real.

I'm still fascinated by Kot, even though I've dropped all of his Image books because they're just not doing it for me. Maybe he does need to head into corporate comics for a while to get a better feel of how to pare down his writing. This is a pretty good example of what he can do when he reins it in just a little bit!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

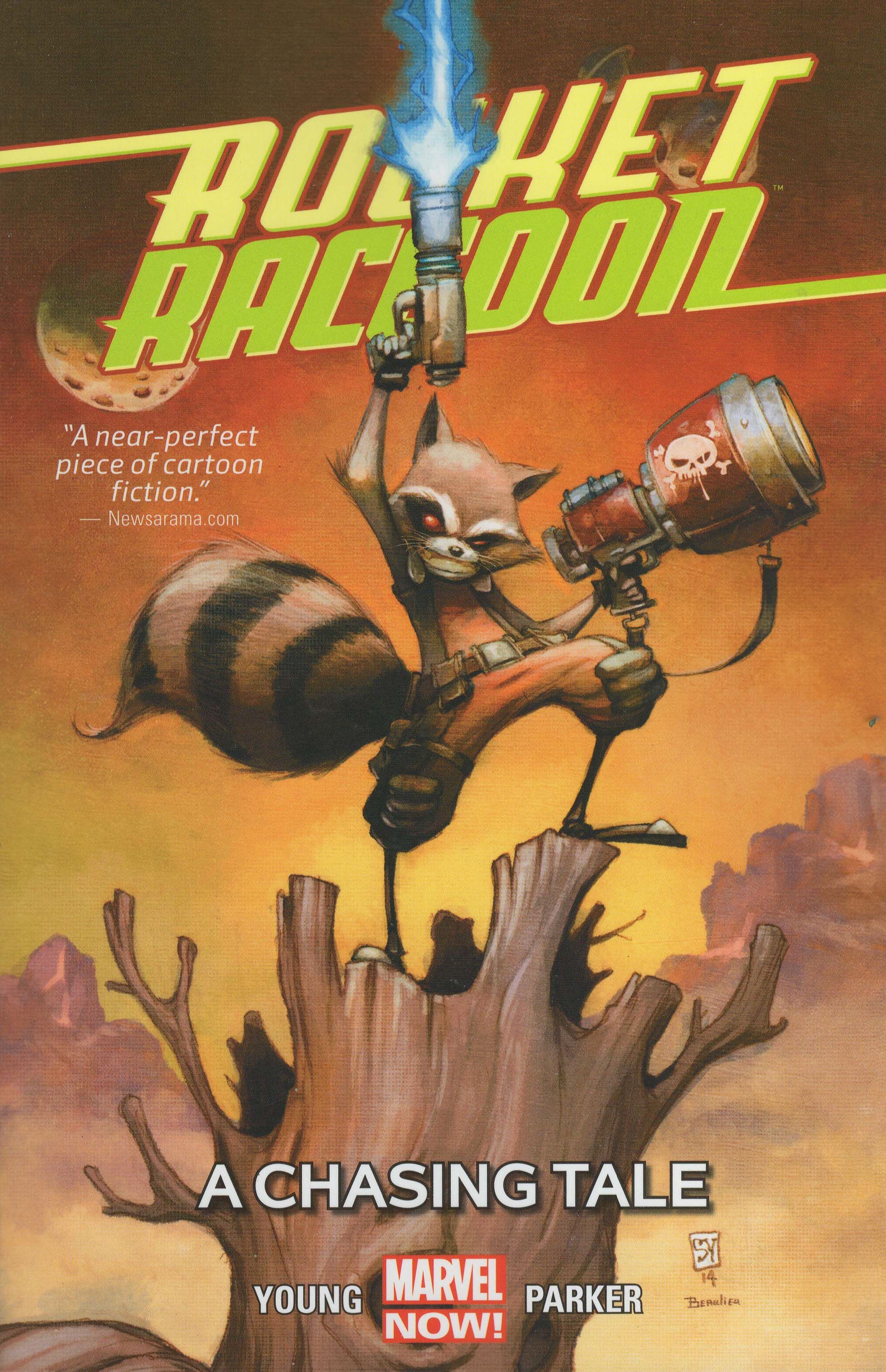

Rocket Raccoon volume 1: A Chasing Tale by Jean-François Beaulieu (colorist), Jeff Eckleberry (letterer), Jake Parker (artist), Skottie Young (writer/artist), Sarah Brunstad (assistant editor), and Jennifer Grünwald (collection editor). $19.99, 120 pgs, FC, Marvel.

This comic is astonishingly mediocre, and I weep because of it. Skottie Young can draw anything and make it look great, and Parker, who draws issues #5 and 6, is a solid replacement for him who draws in a similar style with slightly less insanity. There's so much fun on these pages, from the teleporting fish to Groot's wrestling match. Young designs all sorts of crazy spaceships and monsters and aliens, and his cartooning is tremendous, as Rocket and Groot tumble through the pages, causing mayhem wherever they go. His action scenes are great, and the big battle in issue #4 is beautifully choreographed and just the slightest bit silly, as befits the tone of the book. Young uses exaggerated facial expressions and body language, of course, because that's his style, but he can do a good job with some of the more emotionally draining moments as well - Rocket, remember, is the last of his kind, and Young makes that a crucial plot point. Parker's line is a bit cleaner than Young's, but he can keep up with him when it comes to craziness, and I really wonder if Young laid out a good deal of issues #5 and 6 or if Parker is just really good at not only aping his style, but even his storytelling. Beaulieu's bright colors are phenomenal, making the galaxy look like a really cool place to get lost in. The art is a real treat.

But Young's stories are just mediocre, and it's too bad. The first four issues are one story, in which Rocket is framed for murder and has to find the culprit, with the added bonus of the culprit appearing to be a creature like him even though he believes he's the last of his kind. It's not much of a spoiler to say that it's all a scheme and that Rocket really is alone, but then Young even upends that notion, too. The actual story is fine - Rocket gets thrown in prison, breaks out, tracks down the murderer, and there's a big fight, but it's still not very good. I hate to go all feminist on you, but this is the kind of story that makes me uncomfortable, even though Young is going for laughs. Part of the plot deals with Rocket's ex-girlfriends teaming up to kill him, and this is played for laughs. All of them - not just the ringleader - are portrayed as slightly insane, and of course they fail in their plot. Now, Young writes Rocket a lot like the movie did, meaning he's an obnoxious jerk. All the pathos about every member of his species being dead can't overcome that. But, like a lot of fiction, he's the hero, and because he's funny when Bradley Cooper voices him, he's not going to change. So while he's a total jerk to all these women and they have legitimate reasons for hating him (mainly that he treats them like interchangeable parts), Young can't make him acknowledge that he's a jerk and try to change. He does realize why they're all coming after him, but they're the bad guys, not our poor hero Rocket. It's annoying, because this is pretty common in our culture, and as long as everyone laughs at the movies, Rocket is going to be a tool (he wasn't always one in the comics, as you might recall) but he's going to get away with it. It makes an otherwise decent story - not a great one, but a decent one - and puts a troubling spin on it. Issue #5 is one joke stretched out over 20 pages - Groot narrates, and it goes about as well as you might expect - and issue #6 is a forgettable story about Rocket helping out a robot and its friends who are going to be sold for parts. It's okay. I've never been a fan of Rocket "understanding" Groot whenever he says "I am Groot," and I wonder if it's ever been explained that Groot is really saying other things and Rocket understands him or if Groot only means "I am Groot" and Rocket responds to what he wants Groot to be saying. Either way, it's a mildly funny joke that doesn't really warrant an entire issue.

Young has moved on to Image and his creator-owned book, I Hate Fairyland. I was planning on waiting for the trade of it, but now that I've read this (which is the first thing that Young has written that I've read), I worry that it will be similar to this - amazing to look at, but not much fun to read. We shall see!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

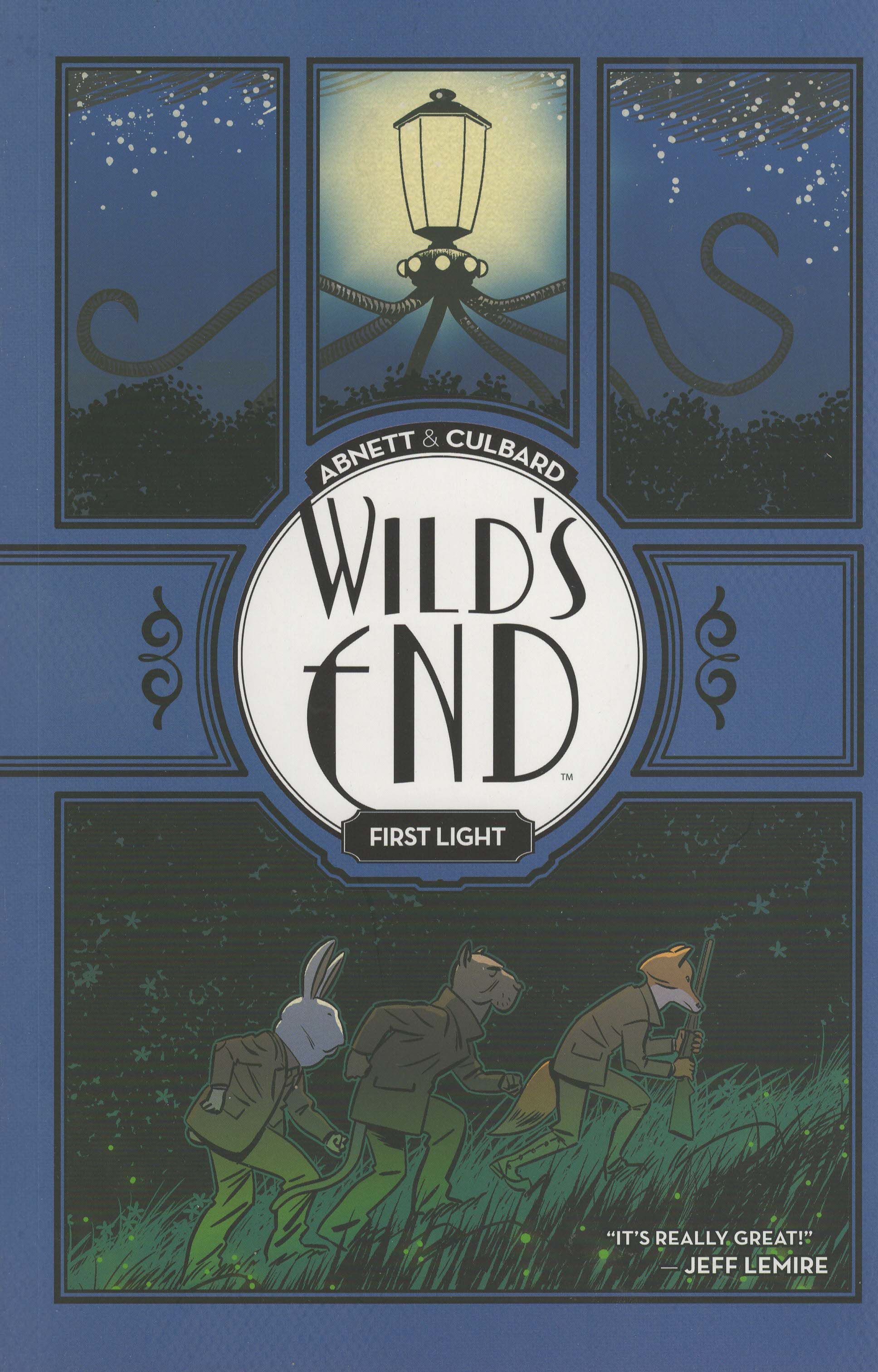

Wild's End volume 1: First Light by Dan Abnett (writer), I.N.J. Culbard (artist/letterer), Cameron Chittock (assistant editor), and Dafna Pleban (editor). $19.99, 144 pgs, FC, Boom! Studios.

I often wonder why writers and/or artists decide to turn the characters in their books into anthropomorphic animals. Does the artist just think, "I'm sick of drawing humans, so I want to try to draw some animals, man!" Does the writer or artist think it would be fun to try to find the "right" animal for whatever personality traits their characters might have? These comics never have the animals acting like, you know, actual dogs or cats of badgers - they always act exactly like humans. I certainly don't mind - Blacksad and Grandville, for instance, are terrific comics - but I wonder why creators decide on it. Is it just a lark, or do they have actual reasons for doing it?

I wonder this because there doesn't seem to be any discernible reason for the characters of Wild's End to be animals. Sure, the animals tend to match the personalities of the characters - Clive Slipaway is a hang dog Great Dane that matches his measured, calm demeanor, for instance - but ultimately, they're just people who look like animals. I get that people can look like animals, and perhaps Abnett and Culbard, along with every other creator who does this, is commenting on that while, you know, not really commenting on it, but other than that, these are just regular English folk. I can't even really write much about this - it's War of the Worlds, basically, with clanky steampunk aliens landing in the English countryside in the 1930s and the attempts of several townsfolk to fight back. Nobody believes the town drunk that aliens have landed, but then dependable Clive realizes that a fire at a kindly pig's house isn't an accident, and then they stumble across an alien, and they have to run and fight. The book is part of a whole - the second volume just started this week, unless that was the second issue - so nothing gets resolved in this. All we know is that aliens have landed and they can be killed (although they're very tough) - we don't even know if the aliens have destroyed the town or if they've landed anywhere else. It's entertaining, and Culbard's art is good as usual, but it's incomplete, and unlike some other parts of a whole, this volume isn't even that satisfying. Everything that happens feels like a prelude, and we don't even get to know the characters all that much - Abnett drops hints about Clive and Susan, but that's about it.

I don't know - it's okay. I'll probably get the next volume. Just don't expect too much resolution in this volume. It's sorely lacking.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

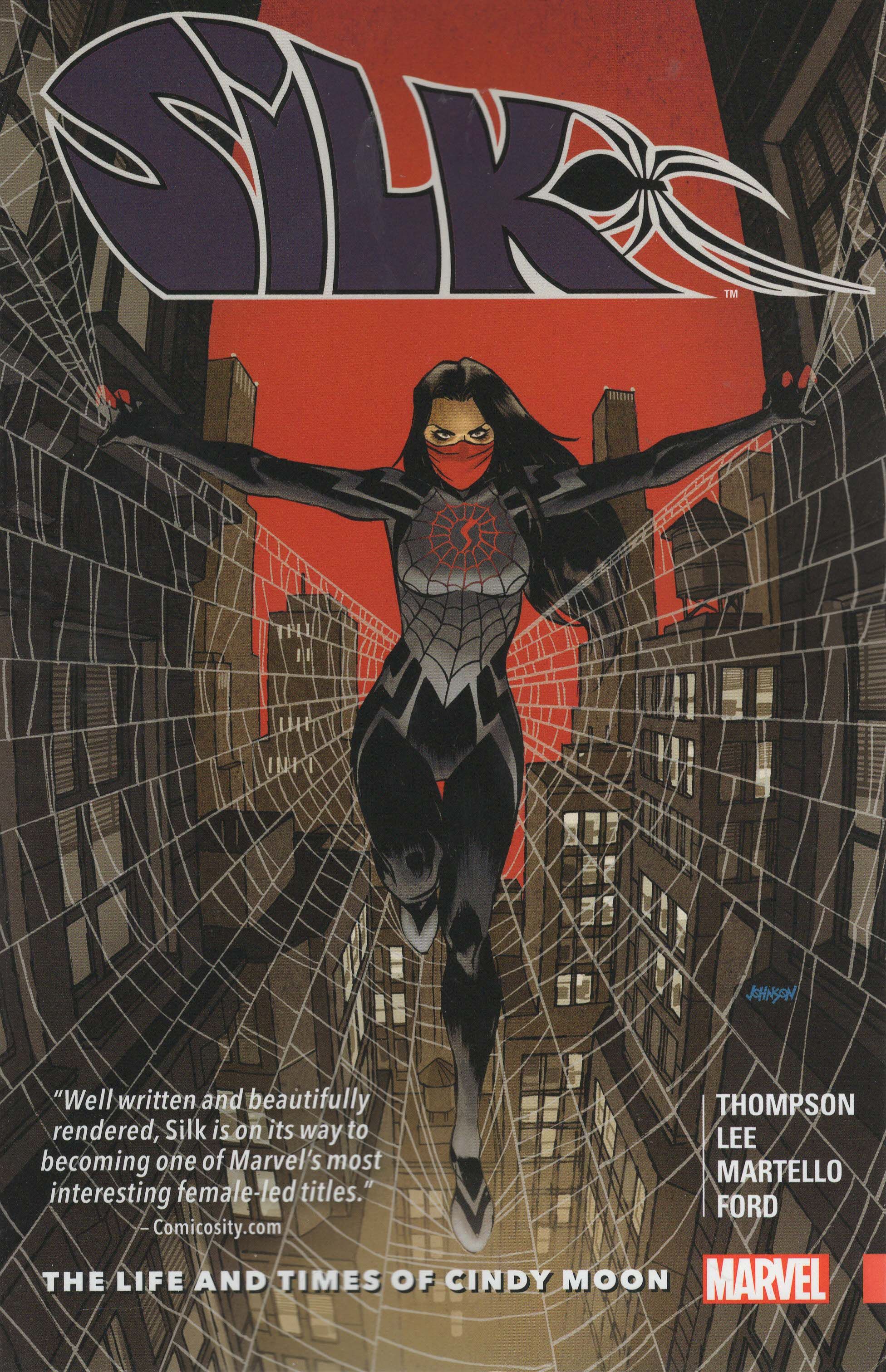

Silk volume 1: The Life and Times of Cindy Moon by Tana Ford (artist), Ian Herring (colorist), Travis Lanham (letterer), Stacey Lee (artist), Annapaola Martello (artist), Robbie Thompson (writer), Devin Lewis (assistant editor), Nick Lowe (editor), and Ellie Pyle (editor). $19.99, 140 pgs, FC, Marvel.

I think I'm too old for a lot of comics these days, especially ones that try to be hip. The worst sin Thompson commits, to me, in Silk is the way he writes 27-year-old Cindy. She sounds like an idiot too often, and when you're going for "clever" or at least "charming," that's not a good thing. This is most noticeable in the first few issues, when Thompson is trying to give Cindy a "voice," and thankfully it eases up a bit in the later issues, but I just think I'm too old. I have never found Johnny Storm terribly charming, but for some reason he comes off as skeevy in this book (he and Cindy go on a date, and it's a nice date, but I'm talking about before that). Maybe it's just that even though Cindy is in her late twenties, Thompson constantly reminds us that she spent 10 years in a bunker, so she still feels like a teenager when you're reading this, as she just seems ... more innocent, I guess? Obviously, she's dating someone when she's 17 and she might even be making the beast with two backs with him, but the combination of the way Thompson writes her, as so naïve (which she probably would be, having been out of the loop for a decade) and the way Lee draws her (she looks like a teenager) makes it seem weird. Like I wrote above, Thompson does ease back on it in the latter part of the book, which is a nice change. He ramps up the plot more, too, so there's a bit less time for Cindy to internal monologue, so there's that. Thompson does some nice things with the story, which is a standard superhero plot - Cindy's family is missing, she's trying to find them, the Black Cat is running some kind of criminal operation that she keeps messing with - he makes one of the main villains an interesting character whom Cindy helps redeem, and Cindy isn't so paranoid about her situation that she doesn't tell J. Jonah Jameson about her missing family (which allows Thompson to remind us that Jameson, when he's not obsessing about Spider-Man, can be a pretty good guy) and she doesn't ignore Reed Richards's advice about seeing a psychiatrist. In a superhero story, you need little touches that set it apart, and Thompson does that, even if I still don't love how he actually writes Cindy. But that's okay.

Lee is fantastic on the book, even though she couldn't keep up with the brutal Marvel schedule (I don't think this book double-shipped, because Marvel thankfully seems to have stopped that, but apparently three consecutive issues is about all we can reasonably hope for with a lot of artists these days) so she only draws 5 of the 7 issues. Her loose line is terrific for a superhero book, and she does really nice work with the way the characters look and dress. Cindy isn't a supremely confident hero, and Lee does a wonderful job with that, as she puts on some false confidence with Spider-Man (who acts weirdly around her throughout, which might be out of character for him, but it's been so long since I read Spider-Man comics that maybe he's kind of a creep now) but Lee shows with her body language that she really is having a hard time doing hero things. This makes her "final" confrontation with Black Cat (I assume that in the new series, Black Cat will come up again) so great, because Cindy has learned how to deal with her, and her fury is hard-earned (I do like how Cindy can chop off a hunk of her hair and still have a great 'do, because COMICS!). Thompson does a decent job writing her as more confident as the book moves on, but Lee draws it wonderfully, because so much of it is in non-verbal cues, and Lee nails them. Martello does a good job with issue #4, and she draws Cindy as more of a woman than a teenager, so it's probably good that that issue is when she and Johnny go out on a date (Thompson still writes Johnny weirdly - what's up with the young men in this series? - and while Lee doesn't draw that issue, her version of Cindy is stuck in my head). Ford's line is a bit more solid than Lee's, and she does a good job on the final issue, where Cindy thinks she has found her brother and goes to see if it's true while the Marvel Universe falls apart (yuck). If Lee can't handle a monthly, at least Marvel found some cool artists to fill in.

Silk is all right - it's a above-average superhero comic, which is always nice to see. I'm sure that if it had come out a bit earlier, Marvel would have broken up the trades into more volumes, but you can't deny that 7 issues for 20 bucks is a good deal, considering that these would have cost you $28 in single issue format. I'm making a bigger effort to switch to trades these days, and this is a very good reason why!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

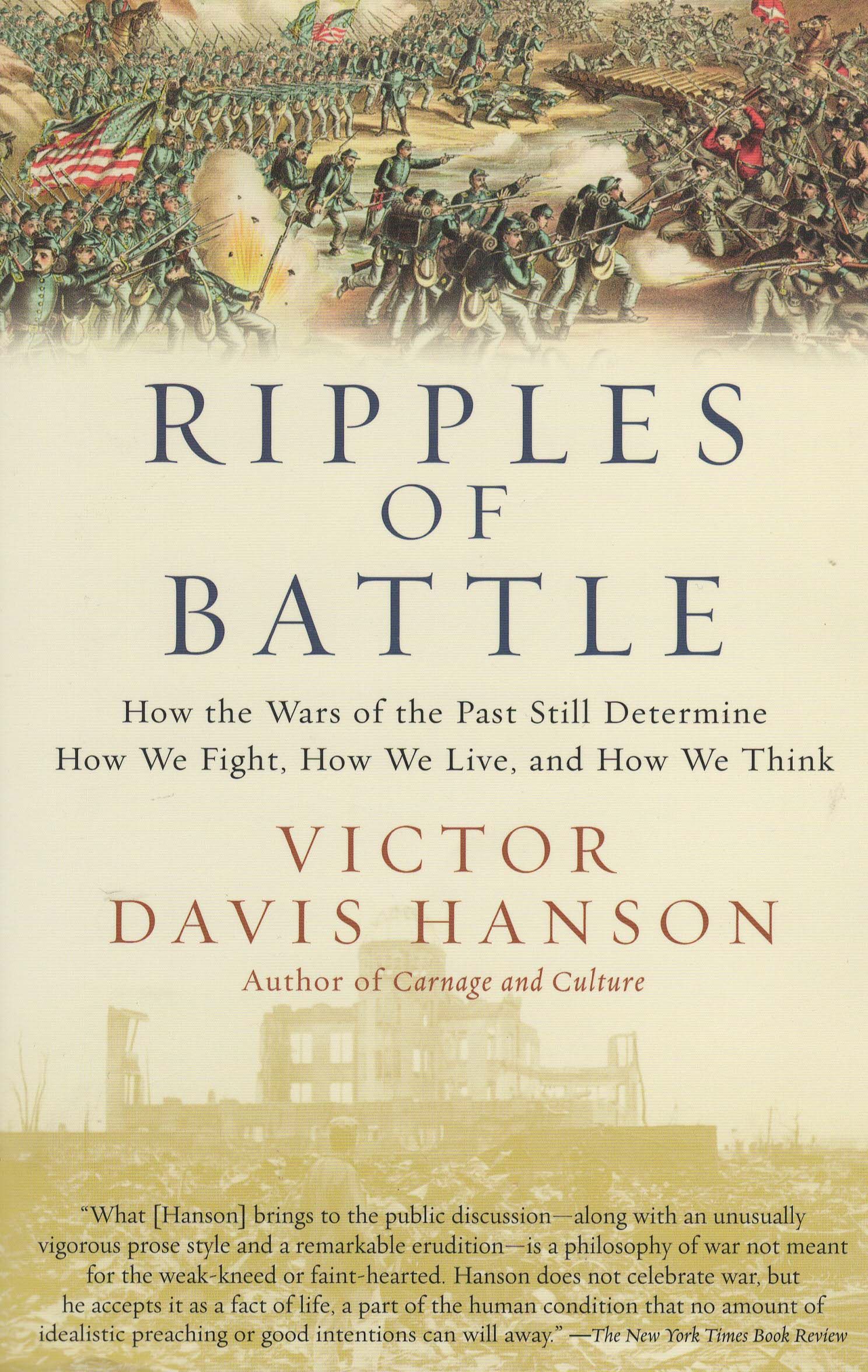

Ripples of Battle: How the Wars of the Past Still Determine How We Fight, How We Live, and How We Think by Victor Davis Hanson. 278 pgs, Random House, Inc., 2003.

I'm not a big fan of Hanson's commentaries on current events, as he's a conservative hawk who thinks war is the answer to almost any foreign policy question, but the dude is a good historian, so his writing in this book is fascinating ... except when he begins commenting on "current events" (the events of 2002, of course), where he gets caught up in the anti-Islamic feeling that was sweeping the country in the aftermath of 11 September (and which continues today, to a slightly lesser degree). He focuses on three battles - Okinawa, Shiloh, and Delium - and examines how these fights shaped the way the world is today, and if you're thinking that the battle of Delium, which was a fairly minor battle fought in 424 BCE, doesn't have any influence on the way the world is now, well, Hanson is happy to tell you you're wrong!

Hanson goes over the battles with a fine-toothed comb, pulling interesting facts from each conflict, indulging in some counter-factuals ("what-ifs," for the laymen) but generally keeping with the actual way the battles have influenced the modern world instead of how they might have. With regard to Okinawa, he makes the point that the brutality of the fighting on the island had a big influence on Truman's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan, as it was clear to the military that the Japanese had no inclination to surrender nor compunction about fighting to the last man. Whether that was true or not, the slaughter at Okinawa pushed the American military machine toward the bomb, with all its incumbent consequences for our world. Hanson examines the idea of suicide bombers as well, and how that damaged the Japanese national psyche after the war. Okinawa, Hanson argues, is not a particularly "sexy" battle of World War II - he cites Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal as the two Pacific theater fights that get more coverage - mainly, he thinks, because of the European war ending about the same time and all the exhausted exhilaration that came from that - Americans weren't particularly in the mood to pay attention to Okinawa in the midst of celebrating their victory on the other side of the world. But it's still very important, Hanson argues.

He delves into Shiloh, which was fought in April 1862, as a crucial turning point of the Civil War - not more important than Gettysburg or Vicksburg, perhaps, but just as important - and his claims are pretty solid. Shiloh is important for a few reasons, one of which is that it's where William Tecumseh Sherman made his reputation. His bravery, toughness, and decisiveness at Shiloh helped wipe away his mediocre career up to that point, and he used his newfound celebrity to make sure Ulysses Grant was not castigated for the quasi-disaster that Shiloh was for the Union side (both sides claimed victory, but both sides could have easily claimed defeat, as well). Grant was almost scapegoated for getting caught off-guard at Shiloh, but he and Sherman were a team, and both propped the other up, so both survived relatively unscathed. Hanson makes the point that Sherman had his revelation about "total war" at Shiloh and in its aftermath, when he realized that he didn't have to defeat the Confederacy on the battlefield but in the minds of the civilians, who needed to be shown that their cause was hopeless. It's an interesting point, mainly because Hanson links it to another crucial element of the battle - the death of Albert Sidney Johnston, the Confederate commander. While Sherman was surrounded by a hail of bullets yet escaped unhurt, Johnston led a somewhat fruitless charge against the "Hornet's Nest" - an enclave of Union soldiers that the Confederates could have easily bypassed but didn't - and was killed. His death, and even the manner of his death (he wasn't shot off his horse, as the wound was seemingly slight, and he died off the field, leading to some confusion as to whether he was dead or not), was somewhat crippling to the South, as Johnston was the one who boldly attacked at Shiloh in the first place (against the advice of other rebel generals), but Hanson explains that Johnston, like Sherman, was somewhat mediocre prior to the battle, but while Sherman's reputation was enhanced by his survival, Johnston's was enhanced by his death. Hanson claims that the myth of the noble South, which was on the verge of victory in the Civil War before "fate" robbed them of it, was born at Shiloh, where the battle would have been won had not Johnston died. Hanson shreds this myth convincingly, but psychologically, the impact of Johnston's death on the South was immeasurable, as Southerners began to believe that if only a few things had gone their way, they would have won the war. This myth is still with us today, and we don't need Hanson to tell us that. The final impact of Shiloh was the reputation-making of Nathan Bedford Forrest, who came out of the battle looking like the only competent Confederate leader in the West, which turned out to be almost completely true. Forrest was another commander (he wasn't yet a general at Shiloh) who made his name in the battle, and of course, his brief tenure as leader of the Ku Klux Klan helped "normalize" the organization in the South. Forrest would not have been offered leadership of the Klan had he not made his name at Shiloh, and the Klan probably would have died the same way several other terrorist organizations that sprang up after the war did.

Delium, which was fought in the seventh year of the Peloponnesian War, is a bit harder to figure out, as Hanson admits that the sources for the battle are few. Thucydides wrote about it, of course, as did Diodorus, while Euripedes wrote a play about the battle and Plato wrote about Socrates, of course. Hanson examines the battle itself, and he concludes that Pagondas, the commander of the Theban confederacy, was probably the first person in history to use tactics on a battlefield other than "Run at the other side and stab as many of them as you can." Many historians have tried to point to Philip of Macedon or Epaminondas of Thebes (from whom Philip may have learned them) as the revolutionary figure, but Hanson makes an excellent case for Pagondas, who was never mentioned before or after this battle and is almost lost to history. Just that would have been enough to make Delium important, but Hanson also points out that Socrates fought in the battle, and had he died, Western philosophy would have been completely different. Socrates in 424 was middle-aged, but he had yet to become the great thinker he would be in the final decades of his life, so Plato wouldn't have had anyone to write about, and so Platonic thought would have been completely different or non-existent (Plato was only six or so when the battle was fought, so who knows what he would have done with his life?). It's an interesting counter-factual, one that obviously still resonates today.

As I noted above, when Hanson dives into the aftermath of 11 September and what it means for the United States, he's on slightly shakier ground, but that's partly because I don't agree with him and partly because, as a historian, he should know that hindsight is the best way to interpret events. With his hawkish epilogue, Hanson himself ignores the lessons he spends the entire book examining, which is that battles change things in completely unexpected ways, and trying to force a narrative from them without knowing everything about the situation is a recipe for foolhardiness. Hanson continues to be a hawk, and that's fine (he's a military historian, after all), but it's clear that he's much more focused when discussing things lost past than when discussing things that are still unfolding. Still, it's a pretty fascinating book!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

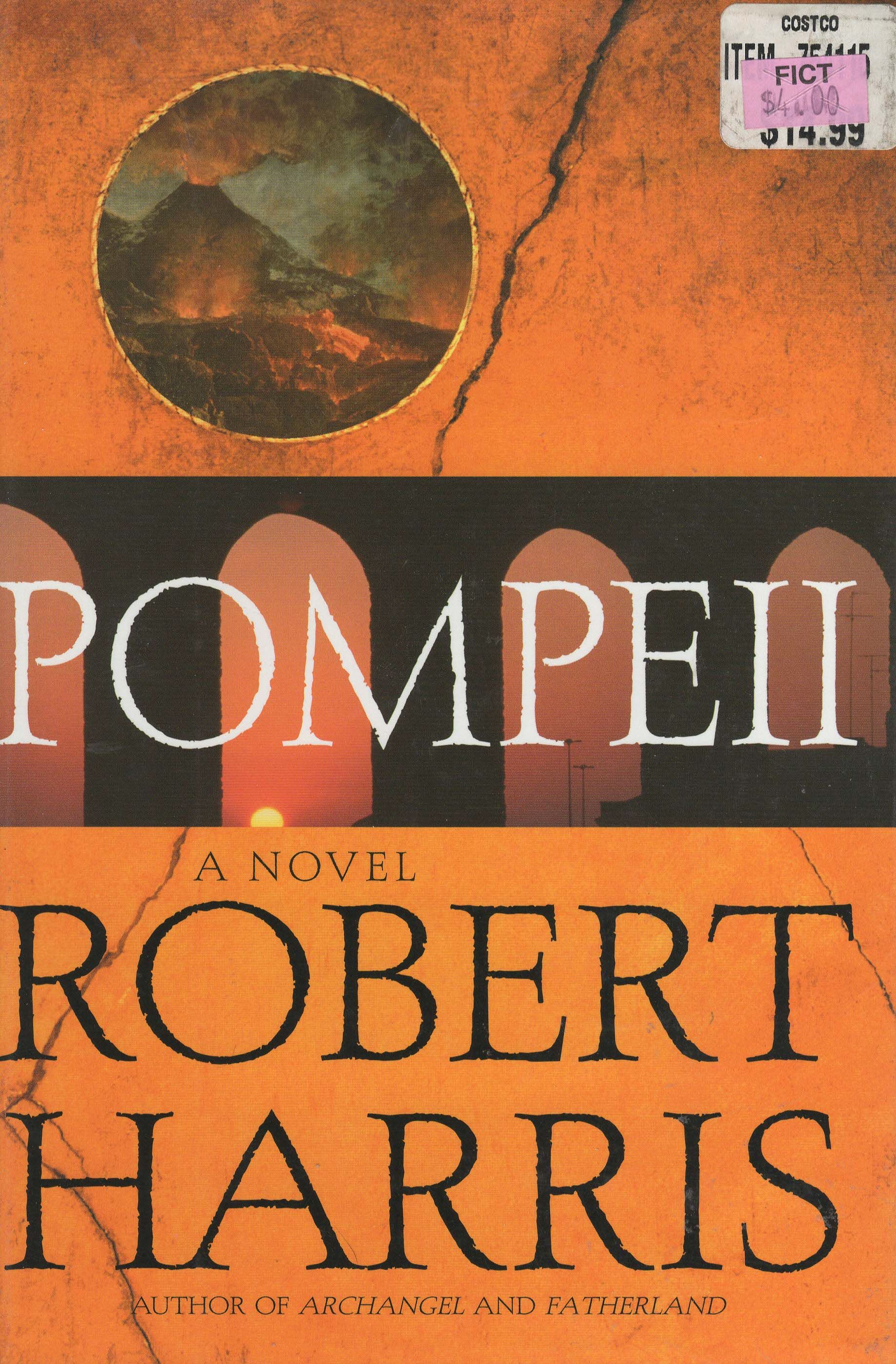

Pompeii by Robert Harris. 278 pgs, Random House, Inc. 2003. (That's weird - this is the same number of pages, the same publisher, and the same year as the book above it. I didn't plan it!)

Robert Harris wrote the brilliant Fatherland, which is alternate-history story set in 1960s Nazi Germany, and he's written some other novels that I haven't read, but Fatherland was so intriguing that I got a few of his other books, including this one, even though I'm not a big fan of books set around famous disasters. It's one of the many reasons I'm not a big fan of Titanic (one of the many, many reasons). I don't like them because the disaster is something no one can really prepare for, and writers usually spend a lot of time coming up with various schemes of the characters that are literally and figuratively wiped out by the deus ex machina of the disaster. It doesn't matter that Billy Zane is a scumbag - the boat's about to sink! So you spend all this time getting invested in whatever plot the writer comes up with before the disaster, all the while knowing that it's not really going to fucking matter once Vesuvius explodes.

Harris tries his best, and the book is quite good until the eruption, which chucks the ultimate spanner into the works. His main character, Marcus Attilius, is an aqueduct engineer sent to the Bay of Naples after the current engineer goes missing. Attilius also quickly realizes that the aqueduct that feeds the entire bay - the grand Aqua Augusta - is somehow blocked, and he begins to investigate that, as the area is in the middle of a drought and it wouldn't do for the citizens to be out of water. He gains an enemy - a rich ex-slave named Ampliatus, who is secretly the most powerful man in Pompeii - and an ally, Gaius Plinius Secundus, otherwise known as Pliny the Elder, who commanded the Roman fleet in the bay. Harris spends most of the book dealing with Attilius's attempts to fix the aqueduct, which leads him to the explanation behind the other engineer's disappearance, a mystery that ties into the corruption at the heart of Roman society, and an attraction to Ampliatus's daughter, which doesn't go too far but is still a good way to get Attilius further involved in Ampliatus's dealings. Obviously, we know Vesuvius is going to blow, and Harris does a good job showing how Attilius slowly figures it out, too. The combination of Attilius's attempts to fix the aqueduct and figure out what the heck is going on while trying to stay ahead of the political corruption in Pompeii makes this a pretty decent thriller. And then the mountain blows up.

The eruption occurs on page 211, so it's not like Harris spends the majority of the book on it. The eruption itself came in waves, and lasted over a day, so there's plenty of time for the plot to still unfold, as it took a long time for the pyroclastic flows to absolutely obliterate Pompeii. Harris does a good job telling the reader how it might be to live through a volcanic eruption, and the book remains exciting, but the only reason things get decided is because so many people die. It's frustrating, because while we do find out what happened to the missing engineer, Attilius escapes one fate through no effort on his part and escapes another fate because, well, the mountain erupts. I know that you can't change history to suit yourself, but frankly, the aftermath of the eruption and how characters reacted to it might have made a better book. Of course, I might be the only one frustrated by stories of this nature. You might think they're groovy!

It's a well-written book, certainly, and Harris has studied up on first-century Rome, so his descriptions of life in 79 CE are really well done. The book is gripping and fun to read, and even though it doesn't end satisfactorily for me, the way he describes the eruption and even the clever way some characters survive is pretty neat. So there's that!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Imperium by Robert Harris. 305 pgs, Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Hey, speaking of Robert Harris and ancient Rome, the next book I read was another one by him on the very same subject! This time, however, Harris goes back to the last days of the Republic and gives us a quasi-biography of Marcus Tullius Cicero, the most famous orator in Roman (world?) history, written by his slave, Tiro, who invented shorthand (see what you learn when you read my posts?). Harris focuses on the period of time from Cicero's dramatic prosecution of Gaius Verres, a governor of Sicily who plundered the province and believed himself above the law due to his friendship with several prominent patrician senators, to Cicero's election to the consulship, the highest office in Republican Rome. Cicero first heard of Verres's case in 75 BCE, successfully prosecuted him in 70, and won the consul seat in 63, so the book doesn't cover too much time, but those years were when Cicero first announced himself as a major player in Roman politics (prior to that he had made his name as a defense attorney) and then reached his greatest triumph. Harris doesn't get into the last 20 years of his life, which is too bad, as there was plenty of intrigue there, but such is life. Perhaps, as Cicero was a great defender of the Republic, he didn't want to write a Cicero who had to know he was fighting a losing battle, as first Julius Caesar, Marcus Crassus, and Pompey tried to undermine it, and then, shortly before Cicero's death, Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Lepidus finished it off. Harris leaves Cicero at the apex of his life, which isn't a bad place to leave him.

The book is a wonderful examination of Roman politics and how men played it. Because of his shorthand, Tiro is often there to record what happens when Cicero makes a speech or even takes a meeting, and in one scene, he eavesdrops on a conspiratorial meeting that presages Caesar's and Crassus's attempts to dominate Rome. Cicero is a fascinating character in the book, because he is an honorable politician even as he switches sides (reluctantly) and betrays some of his principles. Harris obviously used a lot of primary documents - this period of classical history is one of the best-documented - so that Cicero's speeches are almost verbatim and indicate how good he was at writing them and giving them. The politics are fun to read about, too, because Harris does a good job explaining the corruption and how Cicero (and others) uses it for his own ends. The legal aspects are interesting, too - during this time, anyone could claim to be a Roman citizen and the person prosecuting him would be legally bound to investigate the claim before proceeding, a point which Cicero uses against Verres quite well. Harris also does a nice job showing the power of women in Rome - obviously, they had no overt power, but Terentia, Cicero's wife, proves to be almost as clever as he and very helpful in some of his darker moments. In historical novels set before women had any agency, good writers know when to show how they changed things behind the scenes, and Harris is good at that.

The book is well-written and quite a page-turner, and although, like with Pompeii, we know what's coming, I don't mind it as much, because I knew it wasn't going to be a disaster, but the schemes of men that would lead to Cicero's consulship. That's far more interesting than a mountain blowing up, but you mileage may vary, I suppose. We might know exactly where Harris is going, but he turns the journey into a nice thriller, with all sorts of twists and turns, with one man using his brains to outwit those with far more material resources (Cicero wasn't from the ancient aristocracy, so he had to scrounge for money quite a bit). For a book that hinges on speeches, it's far more exciting than it has any right to be. But that's pretty keen!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Dope Machines by The Airborne Toxic Event, Epic Records, 2015.

You might be forgiven, if you happened across Dope Machines and knew nothing about it, if you believed it was released by a New Wave band in, say, 1983. It's really weird, and not necessarily in a good way. The Airborne Toxic Event is one of my favorite current bands, and I can find plenty of good stuff on this, their fourth album, but it's like the band really wanted to release a New Wave album from 1983, so they did. If you like an excessive use of drum machines and spacey keyboards, you'll probably dig this album. I don't love it mainly because their two previous releases, All At Once and Such Hot Blood, were so good, but I still like it well enough. Mikel Jollett is an excellent lyricist, and the band are good musicians, and there's just enough of an edge to some songs that it makes it worthwhile. It's still a weird album. "Wrong," which begins the album, has a poppy, reverb kind of thing going on, and Jollett is always good at a cri de couer, so when he wails the chorus, "I believe I was wrong, probably most of my life," you believe it, but the music doesn't match the lyrics well enough. Then we get the second song, "One Time Thing," which again is drenched in keyboards, which makes it sound a bit lightweight. Like a lot of the band's songs, Jollett crescendos nicely, and the instrumental section in the middle whines nicely as Jollett brings it home, but it's still a strange. This version, with Anna Bulbrook playing the violin instead of the keyboards, is a more powerful song, and why that's not the "official" version is puzzling. The title track, which comes next, is more of the same. There's a good, crunchy guitar in it, but the drum machines are almost overwhelming. Again, Jollett's lyrics and singing are perfectly fine, and the actual musicianship is good, but the choices about the way the music sounds remain odd. The two best songs on the album come in the middle, with "California" and "Hell and Back." The first song still has an eerie sheen to it, but it has a breezy tone to it that contrasts really well with the dark lyrics, which is about people going to Hollywood to make their fortune and finding nothing but darkness. "Hell and Back" is a terrific song, bluesy and scuzzy, with the band not abandoning their devotion to electronica but incorporating it better into the guitar-driven rock they usually play. Then, unfortunately, they go a bit inert with the next three songs, "My Childish Bride," "The Thing About Dreams," and "Something You Lost," which not even Jollett's lyrics can save, although the slow build-up on the last song is a game attempt to rescue it. The final song on the album, "Chains," gets us back to the urgency missing from the previous three songs, and Jollett does a good job making it sound so, and we get some nice, throbbing music backing him up, although it still sounds a bit too passive at times. It's weird.

All in all, Dope Machines feels like something Jollett and the band wanted to get out of their system rather than a fully-realized album. There are songs that could be great if different instruments had been used or if they had been mixed better, but too many of them sound like hesitant demos rather than full-fledged songs. The band obviously can still do what made their first three albums so good, and while I don't mind if they play with more drum machines and keyboards in the future, it would be nice if they pushed the sound more to the background. I guess we'll have to see, won't we?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Run by Awolnation, Red Bull Records, 2015.

Speaking of disappointing records, while Dope Machines is slightly so but still pretty good, Run is not good at all, which is a tremendous disappointment, considering how good Megalithic Symphony was. I can't even think of one song that's really good. They're either drudging and dank ("Run", "Jailbreak"), enervating ("Fat Face", "Headrest for My Soul"), or incomprehensible (Kookseverywhere!!!"). The two songs that have some verve to them are "Hollow Moon (Bad Wolf)" and "I Am", and even those two aren't that great, especially compared to the excellent songs on their first album. The album really devolves in the second half, as we get more oddball angry songs and more soporific ones ("Dreamers", "Windows", and "Like People Like Plastic" are examples of the former, while "Holy Roller" and "Lie Love Live Love" are examples of the latter). It's just annoying, because if a band makes a disappointing album, there are usually some songs that show they just made a misstep, but there's really nothing that memorable or good on this album. With a lot of albums, I have trouble typing stuff on this here computer while listening to them because I keep getting distracted by the songs that I like to sing along to. With Run, I don't have the problem at all. Too bad. Maybe their next album will be a nice rebound!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

Bad Blood by Bastille, Virgin Records, 2013.

On the other hand, Bad Blood is an album with no bad songs (only one, "Get Home," is kind of mediocre), and a bunch of excellent songs. I can't really express how much I dig this album - the songs are short pop masterpieces, with singer Dan Smith taking specific things and making them metaphorical almost effortlessly. "Pompeii", for instance, is certainly about a volcanic eruption destroying a city, but it's also about past sins coming back to haunt us. "Things We Lost in the Fire" is definitely about losing things in a fire, but it's also about the destruction of a relationship. "Icarus" is always an easy metaphor, but that doesn't mean it's ineffective. My favorite song on the album is probably "Flaws", mainly because it takes something that could be heart-breaking ("When all of your flaws and all of my flaws are laid out one by one") and turns it into something triumphant ("Dig them up, let's finish what we started; dig them up so nothing's left unturned"). The bonus track, "Weight of Living, Pt. I" ("Part II" is on the "official" part of the album), also because it takes what could be a depressing lyric (albatrosses around necks) and turns it into something hopeful ("Your albatross - let it go, let it go"). The music is terrific, too - it's fast-paced, not too poppy, with an old-school vibe that doesn't, like in the case of Dope Machines, sound like slavishly aping 1980s synth rock but which takes its inspiration from it and turns it into something new. Bastille can get crunchy, like with the foundation line of "Bad Blood", or spacey, as in "Weight of Living Part II". They can be mysterious and thunderous, as we get on "Laura Palmer". There's just so many great songs on this album, and I'm glad I picked it up. Check it out!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆

A Badly Broken Code by Dessa, Doomtree Records, 2010.

This is Dessa's first solo album, which I got after getting her second and third ones, which is why this is a bit frustrating. Six of the songs on this album show up on her second, Castor, the Twin, and while the theory is that the first version of any song you hear is your favorite (I don't know if that's true, but I've read that theory), in this case, I think it's true, as the songs on this album sound more like demos, while the versions on Castor, the Twin sound more like actual songs. Now there are 15 songs on this album, so 9 of them are "new" to me, but it's still frustrating, especially because some of those "new" songs are just okay. "Children's Work" opens the album with a tinkly piano part and a pulsing beat and Dessa's typically excellent lyrics, culminating in the creepy chorus: "Now I've learned how to paint my face, how to earn my keep, how to clean my kill." "Matches to Paper Dolls" is another terrific song, with eerie violins over a great story about lovers who are really bad for each other - "You flash some fang, and I bat my lashes, and we're back again." "Seamstress" is as close to pure hip-hop as we get on the album, with a steady guitar beat behind Dessa's rapid-fire verses. "Dutch" is a slow-moving creep, with our heroine snaking her way through a freedom anthem, her voice dripping with contempt for fools. In the same vein, "The Bullpen" is a rant against a male-centric world of music - "Sometimes I hate this business / It's all love backstage / But then the boys get brave / Gotta say, I hope your mother doesn't listen." "Crew", however, is a paean to Doomtree, the band she started with, and it's a charming song about sticking with your "clan." Some of the songs - the slower ones - don't work as well, and it seems that Dessa just isn't that great at slowing things down, but that's okay. Even with the songs from the second album, this is a good piece of work. It's not quite as good as her second and third albums, but that's to be expected, isn't it?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Sonic Highways by Foo Fighters, Roswell Records, 2014.

Unless you just hate the style of music, Foo Fighters release only good albums - they haven't really had a clunker yet, unless you count their first one, which was a bit uneven. What they do, however, is release great ones and just decent ones, and Sonic Highways falls into the latter category (The Colour and the Shape and Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace are their two great albums, while Foo Fighters and In Your Honor are their two worst; this falls somewhere in between). There are only 8 songs on the album, so for it to be great, they kind of have to hit on all of them, but they don't. I'm not even really sure what the deal is with the "musical influences" of various places in the country - I guess the lyrics are supposed to be reflective of something in each city, but the lyrics are generally fairly vague, and the music itself is classic Foo Fighters, so it's not like they played zydeco on "In the Clear," for instance. This album is a bit better than Wasting Light, mainly because Grohl screams at better times and less often, and Grohl's screaming is always something that should be done in moderation. However, the album lacks a great song like Wasting Light has ("Walk," in case you're wondering), so it's a bit vexing. "Something from Nothing," "Outside," "In the Clear," and I Am a River" are all good songs, and that's half of the album, and the only one that really doesn't work in "Subterranean," so I guess that's not bad. Dave and the gang have been playing the same music for 20 years now, and occasionally they throw down some transcendent songs, and sometimes they just give us some good ones. That's what Sonic Highways is.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

La Petite Mort by James, BMG Rights Management, 2014.

Since they reunited after their 2001 break-up, James has released their best album, two EPs that might as well be one album, and now La Petite Mort, which isn't quite as good as Hey Ma (2008) but can stand with the mostly-great James albums of the past. James is one of my favorite current bands, but they always have about 2-3 clunkers on every album (which is why Hey Ma is their best, because there's only 1, at the most). Their albums also almost always start really strong and then taper off, occasionally rising with the final track back to what makes them great, and La Petite Mort follows that arc perfectly. The first 6 songs and the final one are the good ones, and the 3 in between are just okay. But that's not a bad ratio, I guess!

The album kicks off with a James classic, "Walk Like You," with the band playing their jangly, up-tempo music that morphs into early 1990s Manchester house, almost, all while Tim Booth sings about themes near and dear to his heart - the idea of becoming our parents and how horrifying that is. "Curse Curse" is more of Booth's favorite stuff - sex and religion, with sports getting blended into religion, as it's a nice pro-masturbation tune, and aren't those always nice? The band keeps up nicely, with the keyboards turning it into a crazed, fuzzy dance. The single, "Moving On," is another typical James song. Booth is good at being both a bit sad and a bit hopeful, and he does it here - "Strong yet open-hearted, accept leaving when leaving's come" - and the band loves horns, so we get a nice blast of those in the tune, as well. Booth has always written really nice songs about death and loss, and this is one of them. After that, "Gone Baby Gone" is a decent tonic, at least musically, as it's about as funky as James is ever going to get, with a low-throated guitar riff and Booth's filtered voice almost mocking someone for feeling bad about the end of a relationship. The song ends humorously, too, as Booth sings "Love, love, love" over and over before switching to "Blah, blah blah." Booth can be extremely sincere, but he can also be quite cutting, and this is a good song for that. "Frozen Britain" is a bit more bouncy and more joyous, and Booth's whine - which is part of his charm - seems more pronounced on this song, as he's singing about losing his virginity. "Interrogation," the next song, is a neat, paranoid song that lopes along with some really nice trumpet providing an eerie backdrop to Booth's lyrics. The next 3 songs are mediocre - they slow down and drag, and Booth doesn't do much to lift them up - but the final song, "All I'm Saying," is the kind of slow James song that works - it's creepy and even spooky early on, with Booth once again singing about loss and death before the guitar comes in to speed things up before everything expands into something more hopeful that still retains its sad edge (the official video is pretty awesome, but it doesn't start off quite as creepily, to the song's detriment). It's a very nice way to end the album, but that's never really been a problem with James. It's always the few songs in the middle that get them!

Overall, this is a good album from the band. It sounds like classic James, but they always try a few new things to keep the music fresh. I'm already looking forward to the next one!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Well, that was fun, wasn't it? As I slowly but surely move to trades, I'll have to figure out what to do instead of doing a gargantuan monthly post (I didn't even get to quite everything I bought this month, but such is life). We shall see!

I hope everyone had a nice Halloween. I don't like it, but plenty of people do!