I do these fairly haphazardly, don't I? Oh well - that's the way it is!

Bacchus volume 1 by Eddie Campbell (writer/artist/layouter), Ed Hillyer (finisher), Pete Mullins (artist), Woodrow Phoenix (letterer), and Wes Kublick (writer). $39.99, 557 pgs, BW, Top Shelf.

Top Shelf is going to release two large volumes of Bacchus, collecting all of Campbell's sprawling epic, which is very nice, as the publication history of the character is spread out over many different titles and publishers. Campbell, despite working on at least one stunningly great comic (From Hell), isn't as well known as he probably should be, so anytime there's a chance for more of his work to be collected between two covers so that fans can read it in one place, it's a good thing. There's just one problem:

Bacchus just isn't that good. It's a mess, frankly, as Campbell claims he wanted to create an "American-style comic book" that happened to star Greek gods - by "American-style," he means a genre "in which characters routinely have impossibly exaggerated abilities" - but he's just not that good at it. The gods might have exaggerated abilities, and there's some "American-style" violence in the book, but it's well over 500 pages, and far too much of it is dedicated to Bacchus sitting around drinking wine while his pal Simpson philosophizes poorly on idiotic subjects. It's wryly humorous, I suppose, but not enough to get through the dull parts, of which there are many. Like many myths, there's no internal consistency, which is fine with myths because they're usually short, moralistic tales, but in an epic, it gets old pretty fast. Campbell gives us Joe Theseus, who's a gangster at the beginning of the story but soon goes through the dullest existential crisis in history. We also are introduced to the Eyeball Kid, who killed Zeus and stole his power. The Eyeball Kid is comic relief, but like far too many comic reliefs throughout popular culture, he's "on-screen" far too often, and his schtick (he's full of malapropisms and tends to crash more serious proceedings a lot) isn't good enough to support the amount of time devoted to him. This is a fairly surreal story, which is fine, but Campbell and his collaborators can't seem to make up their minds about which way they want to go. If this is supposed to be a surreal look at the way myths still influence the world, it's not surreal enough. If it's supposed to be an adventure, it's not adventurous enough. It's a weird hybrid of various styles (not surprising, considering it was created over a decade), none of which really work all that well. There are entertaining bits, but they either drag on too long or are interrupted by dull portions. Bacchus himself is a bit of a void, as he doesn't have many strong characteristics, which might work for a god but not for the central character. He's wildly passive, which I suppose is the point, but it also makes him difficult to care about or even pay attention to. It's very frustrating.

Campbell's art is Campbell's art - if you know what kind of artist he is, you either like him or you don't. He doesn't draw the entire book - Books Two and Four are largely by Hillyer over Campbell's layouts, although they did have a falling out, according to Campbell in the annotations, but I guess Hillyer still finished all the pages. Hillyer's art is more cartoonish and less rigid than Campbell's, and as his chapters are devoted to the Eyeball Kid and (to a lesser extent) Joe Theseus, that style works well with the goofier aspects of those stories. Campbell's more sedate chapters are beautiful, but again, they're in service to a story that just doesn't work very well.

I know that Bacchus has a very good reputation among comics literati, and it does bug me that I don't like it more. I like Campbell's writing, even though I haven't read a ton of it, but this just doesn't work. It seems like its ambitions outstrip the abilities of the creators, which is not the worst thing in the world, but doesn't make it worth a read. It can be entertaining, and it generally looks very nice, but overall, it's a disappointment. Oh well.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

Creepy Presents Alex Toth by Gerry Boudreau (writer), Nicola Cuti (writer), Bill DuBay (writer), Leo Duranona (penciler), Archie Goodwin (writer), Carmine Infantino (penciler), Rich Margopoulos (writer), Roger McKenzie (writer), Doug Moench (writer), Steve Skeates (writer), Leo Summers (penciler), Romeo Tanghal (penciler), Alex Toth (artist/writer; inker on four stories), Dan Braun (consulting editor), Roxy Polk (assistant editor), and Philip R. Simon (editor). $19.99, 162 pgs, BW, Dark Horse.

Even though my Year of the Artist is finished, I'm still going to buy old comics that are getting collected, in this the Golden Age of Reprints. I didn't feature Alex Toth last year not because I don't like Toth (that would be crazy), but because I just didn't have a lot of his work. I still don't have a lot, but just this year I've gotten Bravo for Adventure and now this collection, so my Toth work is shaping up nicely.

These stories are from many different time periods - the earliest is from October 1965, while the latest is from February 1981 - and they show Toth at various stages of development - not necessarily in his basic style, because I own some of his Zorro comics from the 1950s, and he really didn't change that much after that, but with the different techniques he used and different inking styles. His 1960s work tends to feature heavier, thicker inks, while in the 1970s, he seemed to use a lighter brush, so while some of it could be heavy, he was able to do a bit more with grayscales and such. Oddly enough, the 1960s stories from Eerie (of which there are two) seem to be inked a bit more lightly than those from Creepy. Perhaps Toth took the names of the magazines to heart and modified his approach, as the stories in Eerie (until the two stories about "The Hacker" that finish the volume, which are a bit gorier but are also from 1975) tend to be a bit less, well, creepy. The last story he drew for Creepy, which was drawn probably in 1979, is Toth going very minimalist and slightly abstract, as it's all thin lines and chunky blacks, with very little nuance. The stories he inks are interesting, because Toth, like other great inkers, could both complement and overwhelm the artist, and all of them are very "Tothian" to certain degrees. I've never seen Leo Duranona's art before, but Toth's inks give it a very John Severin kind of look. Leo Summers seems like a decent fit for Toth's inks, as his pencils are somewhat minimalist, like Toth's often were. Romeo Tanghal's pencils resist Toth's influence the most, as the inks are very nice but don't turn the art into "Toth-lite," and while I'm not as familiar with Infantino's work as I should be, his work is unrecognizable under Toth's heavy, moody inking. The most interesting stories in the book, art-wise, are "Phantom of Pleasure Island," which features Toth's renditions of Humphrey Bogart and Joan Crawford in a strange, well-lit noir story that Toth still manages to drench in blacks; "Proof Positive," which he also wrote and for which he used a fuzzier brush, making the story appear to be photographs from 1873 (when it occurs) instead of drawings; and the two Hacker stories, where he uses grayscales really well to create late nineteenth-century London. Toth knows when to use smaller panels to speed things up, when to change the panel shapes and use ragged panel borders to create tension and a sense of vertigo, and in one story, he uses small panels set against a black background to create a feeling of claustrophobia. All the stories are beautifully drawn, naturally, and it's neat to see Toth trying all kinds of different things.

The stories are generally good - Goodwin writes several of them, and he could write a good short story. You kind of know what you're getting with Creepy and Eerie stories - something bizarre, with a twist at the end, and the writers generally deliver. We get murders, aliens, magicians, cruel ironic punishments meted out to bad guys - you know, good old-fashioned tales to astonish. None really rise above the generic template of these kinds of stories, but they all entertain, and that's really what matters. They serve the art well, and that's why you buy this book.

It's always nice to get yet another reprint of old comics, because it just makes me appreciate comics all the more. This is a keen one, of course, so you should give it a look if you see it lying around your local comic book store. I mean, who doesn't love Alex Toth?!?!?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

Iron Fist Epic Collection volume 1: The Fury of Iron Fist by (wait for it) Dan Adkins (inker), Aubrey Bradford (inker), Pat Broderick (penciller), Jan Brunner (colorist), John Byrne (penciller), Frank Chiaramonte (inker), Chris Claremont (writer), Janice Cohen (colorist), Vince Colletta (inker), John Costanza (letterer), John Drake (colorist), Susan Fox (letterer), Dick Giordano (inker), Petra Goldberg (colorist), Stan Goldberg (colorist), L. P. Gregory (letterer), Dan Green (inker), Larry Hama (penciller), Ray Holloway (letterer), Dave Hunt (inker/colorist/letterer), Tony Isabella (writer), Arvell Jones (penciller), Gil Kane (penciller), Annette Kawecki (letterer), Karen Mantlo (letterer), Bob McLeod (inker), Al McWilliams (inker), Doug Moench (writer), Bruce Patterson (colorist/letterer), Phil Rache (colorist), Joe Rosen (letterer), George Roussos (colorist), Marie Severin (colorist), Artie Simek (letterer), Roy Thomas (writer), Don Warfield (colorist), Glynis Wein (colorist), Len Wein (writer), Bonnie Wilford (colorist), Michele Wolfman (colorist), and Cory Sedlmeier (collection editor). $39.99, 521 pgs, FC, Marvel. Iron Fist created by Roy Thomas and Gil Kane. Colleen Wing created by Doug Moench and Larry Hama. Misty Knight created by Tony Isabella and Arvell Jones. Batroc the Leaper, the Wrecker, Boomerang, Jean Grey, and Cyclops created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Warhawk created by Chris Claremont and Pat Broderick. Master Khan and Spider-Man created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Angar the Screamer created by Steve Gerber, Gene Colan, and John Tartaglione. Iron Man created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Don Heck, and Jack Kirby. Ravager/Radion created by Steve Gerber, Chris Claremont, and Herb Trimpe. Steel Serpent created by Tony Isabella and Frank McLaughlin. Chaka Khan, Sabretooth, and Bushmaster created by Chris Claremont and John Byrne. Thunderball, Piledriver, and Bulldozer created by Len Wein and Sal Buscema. Captain America created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. Edwin Jarvis created by Stan Lee and Don Heck. Wolverine created by Roy Thomas, Len Wein, John Romita Sr., and Herb Trimpe. Nightcrawler, Colossus, and Storm created by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum. Banshee created by Roy Thomas and Werner Roth. Moira MacTaggart created by Chris Claremont and Dave Cockrum.

This is a terrific collection, full of exciting stories, fun characters, really good art (even before Byrne took over in Marvel Premiere #25), and all-around 1970s goodness. We get everything we need to know going forward with Danny Rand - his origin, some of his background, his new allies, plenty of enemies - and the writers just go nuts with the characters. We get the introductions of Colleen Wing and Misty Knight, who become his steadfast allies; Jeryn Hogarth, Danny Rand's lawyer; Ward and Joy Meachum, brother and daughter of the man who killed Rand's father and who believe Iron Fist took his revenge and became implacable foes (although Joy eventually learned the truth); and a bevy of villains, from old ones like Master Khan to new ones like some dude named Sabretooth. Like so many comics before the Great Decompression, the various writers don't pause for breath too often, throwing so much at the wall that it makes current comics read like a treatise on paint drying. The book is remarkably progressive - neither Colleen nor Misty is a delicate flower, and although Colleen does get kidnapped and needs Danny to rescue her at one point, for the most part, she and Misty are equal partners with Danny in kicking ass (although Misty's romance with Danny does seem a bit sudden). Some of the plot points are a bit ridiculous - Misty abandons a pretty in-depth undercover operation just because her mark, Bushmaster, has put a hit out on Iron Fist, even though he's shown he's, you know, pretty tough - but the book is still wildly entertaining. Byrne's art might be the highlight (it's cleaned up here, obviously, but you can tell it would have looked great back then), but the book gets off to a great start with Gil Kane and Larry Hama's rougher art establishing a gritty, urban mood to the street-level heroics of Iron Fist, Arvell Jones does some nice martial arts action, and Pat Broderick does solid work, as his pencils inked by Bob McLeod are much smoother than his 1980s and 1990s work, and when Vince Colletta inks him ... well, he doesn't screw up too much. There's a lot of cool stuff going on in this comic, and it never lets up.

This collection does remind me that when I have Bendis-like status at Marvel, I'm totally pitching a series about Misty and Jean Grey being roommates during the 1970s. A book like that would kick so much ass, especially if the artist is good at making things look like the Seventies. I'd totally read it. Unless I was writing it. It will happen, you mark my words!

So, yeah. Buy this, if you don't own the issues already. It's pretty awesome.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

Kabuki Library Edition volume 1 by David Mack (writer/artist), Shantal LaRocque (editor), and Scott Allie (editor). $39.99, lots and lots of pages (it's really thick and I just don't feel like counting them), BW/FC, Dark Horse.

I have a theory about Kabuki, Mack's art project that turned into his entire life in comics (more or less). My theory states that Mack didn't think his sequential storytelling was getting any better, so he switched to a multimedia project where he could just do watercolors and other kinds of Dave McKean stuff and not worry about, you know, being coherent. It's strange - the first six issues (plus the prologue) form a story about the main character in a Blade Runner-esque future in which she and several others are assassins for a government body that enforces the law rather strictly but also keeps a balance of power among the crime lords. It's a fairly standard dystopian future story, with gorgeous black and white brush work, some obvious multimedia stuff that is pretty seamlessly incorporated into the main artwork, and some problems with flow and stiffness of characters. Mack isn't as good a writer as his ambition, but there's something strange and beautiful about early Kabuki, as the title character navigates the world and discovers a great deal about her past. Then, it seems, Mack got bored with that. Kabuki gets seriously wounded at the end of the first volume, and in volume 2, Mack moved to color and things got bizarre. Kabuki spends the entire volume unconscious, meandering through her own mind and experiencing a lot of memories from her childhood, and Mack slowly moves from pencil work to more watercolors. Without having to worry about storytelling as much, the art remains beautiful, but Mack isn't interested in much more, and his writing hasn't improved. His flights of fancy reek of high school poetry, and there's no plot to speak of - Kabuki eventually wakes up at the end of the volume and we learn that she's a prisoner of another group, but that's about it.

So what's the deal? Did Mack always want to create art pieces, and he thought doing sequential stories would get him a foothold in that world? Did he really want to do comics but got bored with it too easily? His art is absolutely beautiful in the second volume, and while I do like it in the first volume, it's a bit raw, but you can see his potential for comics. He's just not a great writer, which is why I wonder if he's moved toward the static art that we start to see more of in the second volume. Is he self-aware to know this, and he decided he didn't want to do "traditional" comics? Beats me. It's an interesting and bizarre shift, and it makes reading this volume all at once a bit disconcerting.

Neither section is great - the first is better because there's more of a story, and Mack's more "traditional" art is pretty good, but the second is fascinating because of Mack's evolution - but it's still a nifty comic. I had never read Kabuki before, so this was nice to see. I already pre-ordered the second Library Edition, even though I very much doubt if I really need to get it (I still will, but I kind of wish this had come out before Dark Horse solicited the other one, because I may not have pre-ordered it), as I don't think Mack does too much different in later volumes. However, it's a keen book, and it just shows another way to create comics, so that's nice. It's just a bit odd.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

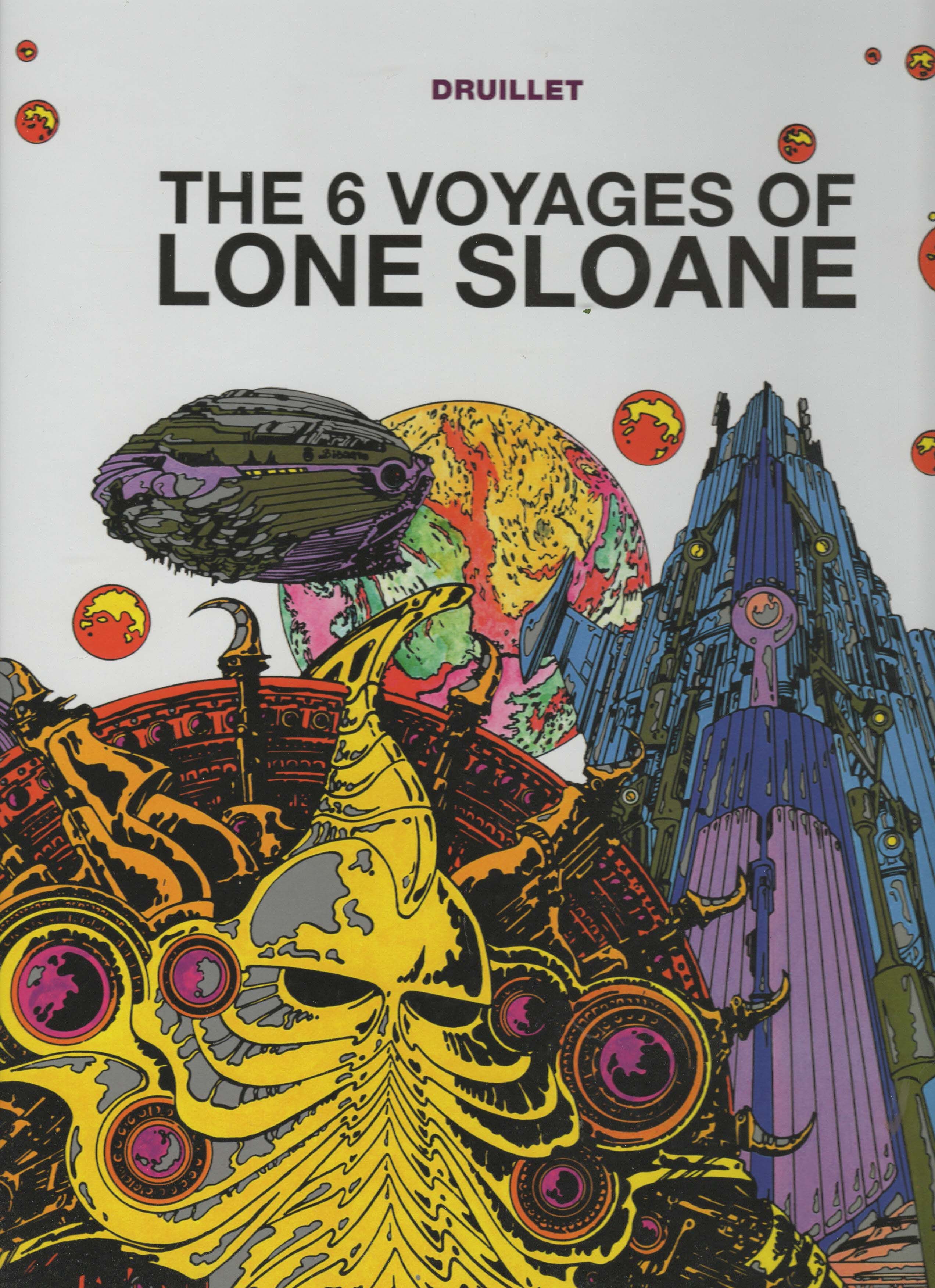

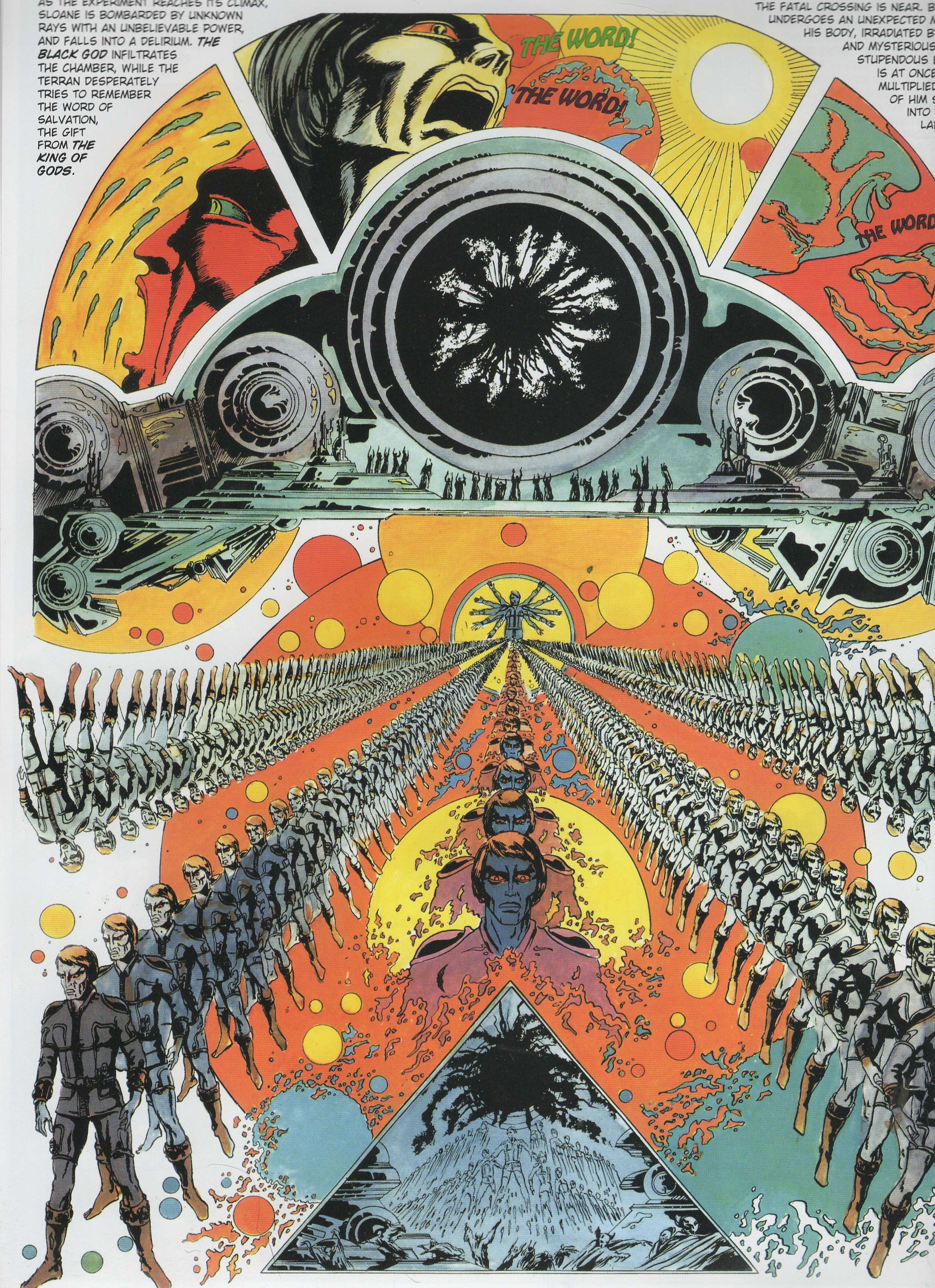

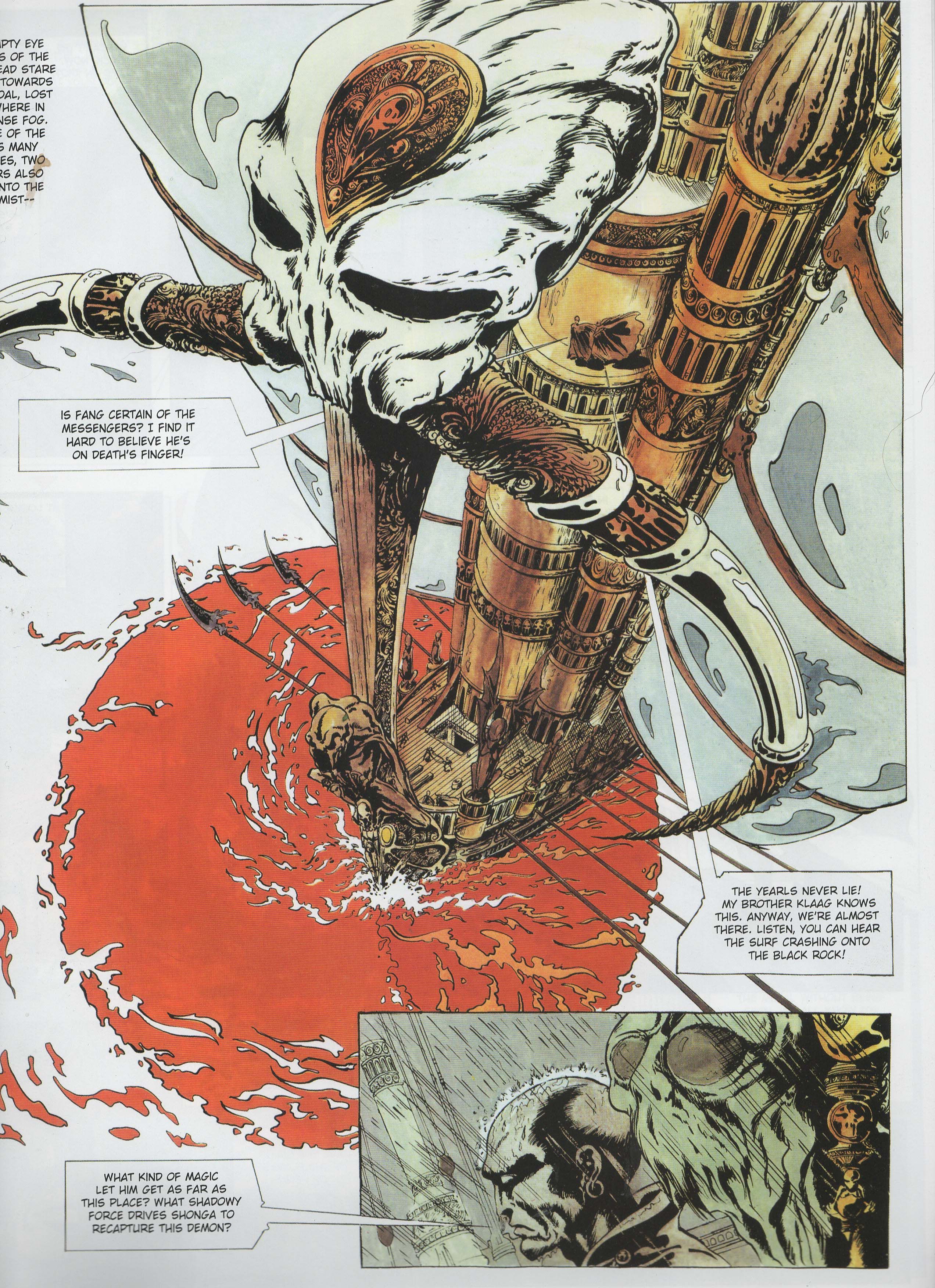

The 6 Voyages of Lone Sloane by Philippe Druillet (writer/artist), Kirsten Murray (assistant editor), and Nora Goldberg (collection editor). $17.99, 48 pgs, FC, Titan Comics.

You might be a bit squeamish about spending 18 dollars for a 48-page comic, but this is a Druillet 48-page comic, which means it's absolutely insane and packed with amazing art, so it does feel a bit longer than your standard 48-page comic. Titan gives us an oversized hardcover, too, so that's something. I had seen Druillet's art before, but I had never owned any of his work, so I'm certainly glad we're getting a nice printing of this comic (which is from 1972 and feels like it, even though it's about the far future). The stories are fairly insane - Sloane is a Terran deep space explorer whose ship explodes on Page 2, but luckily, he gets picked up by a Moebius Chair much like Metron's (how much did Druillet and Kirby know of each other, I wonder?), which takes him deeper into space. Over the course of the volume, he loses the chair (so sad!), but he seems to gain otherworldly powers, and he eventually returns to Earth, where he finds that things have changed quite a lot. The chapters are very slight, as Sloane uses his wiles to thwart bad guys and put himself in a position to return to Earth (he has gained near-mythic status during the course of his travels, so his presence alone makes sentient beings blanch a bit), but because they're so short, it seems really easy for him - he just acts indomitable, and everyone collapses. But that's not the point, really, because the book is completely stunning, art-wise. Druillet creates amazing worlds and amazing things in them, from gargantuan oared boats with cities built on them to organ spaceships (not organic, mind you, but an actual organ) to a wall built across space with pillars on various planets. Yeah, it's that kind of book. Druillet's amazing, ornate details on armor and robots and everything else is stunning, and while he uses panels quite often, he's also not afraid to ditch them altogether and create pages with no borders but which are a holistic whole, telling the story and leading us around the page while still standing as tremendous works of art. It is stupendous work. The closest modern artist comparison would be Marco Rudy, I think, who apparently got ahold of a Druillet book a few years ago and decided that he could do that, too! It's tough to describe the art, so here are some samples - the book is slightly bigger than my scanner, so a bit is trimmed, but you get the idea:

So it's not necessarily something you buy just because you want to see what happens to good ol' Sloane. I mean, the story is perfectly fine, but it's not the reason you get this. You get this just to soak in the visual spectacle. There's nothing wrong with that!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

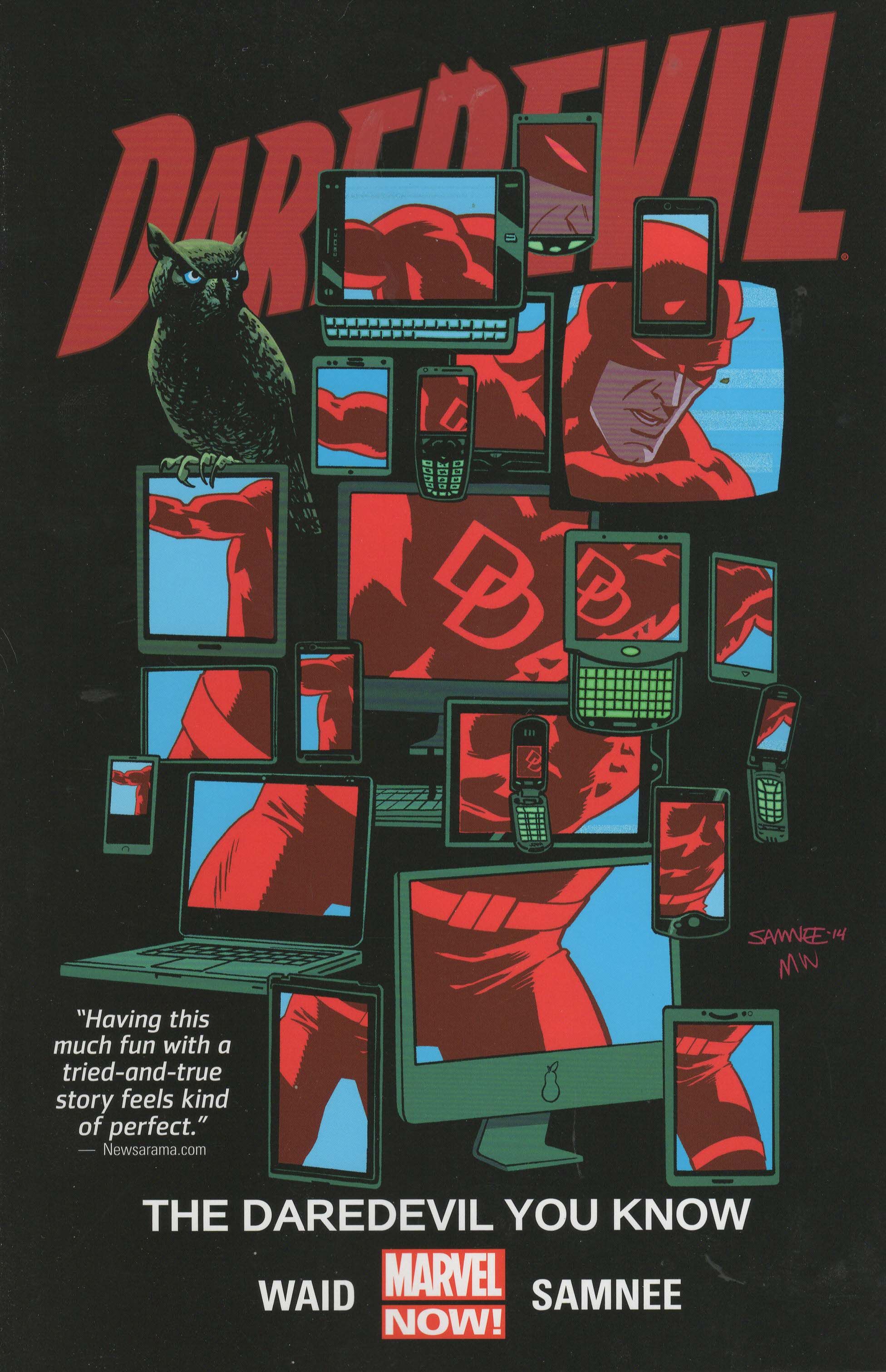

Daredevil volume "3": The Daredevil You Know by Joe Caramagna (letterer), Chris Samnee (artist), Mark Waid (writer), Matthew Wilson (colorist), and Jennifer Grünwald (collection editor). $15.99, 100 pgs, FC, Marvel. Daredevil and Foggy Nelson created by Stan Lee and Bill Everett. Stunt-Master created by Roy Thomas and Gene Colan. The Shroud created by Steve Englehart and Herb Trimpe. The Owl created by Stan Lee and Joe Orlando. Wilson Fisk created by Stan Lee and John Romita Sr.

Although Our Dread Lord and Master frowns on speculating about others' motives, I remain convinced that the reason Daredevil is so acclaimed is because it reminds a lot of people of 1980s superhero comics, before Nineties Bloat settled in and things went a bit crazy. That's not to say they're wrong, because it's a very good comic, but I'm still not sure this would have gotten as much attention had it been released 25 years ago. But that's just crazy speculation, and I enjoy Daredevil as much as anyone else, because it's nice to read a superhero comic from the Big Two in which the writer knows what he's doing and uses the character's history well without being too obscure about it. I mean, I never heard of Stunt-Master before this trade, but Waid doesn't write a story that forces you to figure out who the hell Stunt-Master is, he just uses him and gives those unaware of him enough information that the story works. Waid does make it look effortless, which is why it's so frustrating that more writers don't do it and partly why Daredevil is kind of a breath of fresh air in the catacombs of mainstream superhero comics.

Waid doesn't hit all the right notes, however - the final story in this trade, which leads into the final trade of the series (I guess, as this ends on a cliffhanger), is fine until the bad guy decides to "out" Daredevil - he has recorded everything Matt has ever done, it seems, and is now broadcasting it to the world. Yes, this would be a hassle for Foggy, who's still pretending to be dead, but it seems like a bit of a silly threat in a celebrity-driven, camera-phone world. I certainly wouldn't want anyone to record me for every single second of the day, but this seems less like a serious threat and more something that will blow over the next time a Kardashian "accidentally" flashes someone getting out of a limo. Maybe I'm making too much light of the situation, but it feels like Waid was going for something very serious, so he invented, say, a police threat to Matt even though that's ridiculous. After the clever Stunt-Master story and the interesting situation with Kirsten's abduction, the final few pages seem to artificially introduce stress into Matt's life just so we can get the final page reveal. It's annoying.

Samnee actually draws the entire trade this time, which is nice (Samnee has been very good keeping up with the schedule, but even he doesn't seem to be able to do more three or four issues in a row). I guess for the end of the run, he was pushing himself (or did the schedule slip a little?), and his work is amazing as always. He's become really good at using the entire double-page spread to stretch the panels and give some scenes nice length (this works especially well on the Golden Gate Bridge, but it's not the only place), and his layouts are very neat. There's a terrific page when Kirsten gets abducted on which Samnee gives us a bevy of visual information even though there are very few words, and he makes the way everyone knows everything about Matt visually keen even if the plot is a bit less so. His "Matt Murdock, Douchebag-at-Law" is great, as he gives Matt an amazing suit (I totally want it!) and a swagger that Matt kind of always has (he and Clint Barton are the frat boys of the Marvel Universe) but rarely flaunts so openly. It's great, and it actually makes me feel some schadenfreude when Waid drops the hammer on our hero. Take that, Douchebag-at-Law!

I'm looking forward to how Waid and Samnee (who are credited as "storytellers" in this trade, so I don't know if Samnee helps with the plotting) wrap this whole thing up in the final trade, because, unfortunately, I imagine that they're going to restore the old status quo (don't tell me if they didn't!) before "Secret Wars" rewrites everything. But Daredevil continues to be a charming superhero comic. That's nice to see.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

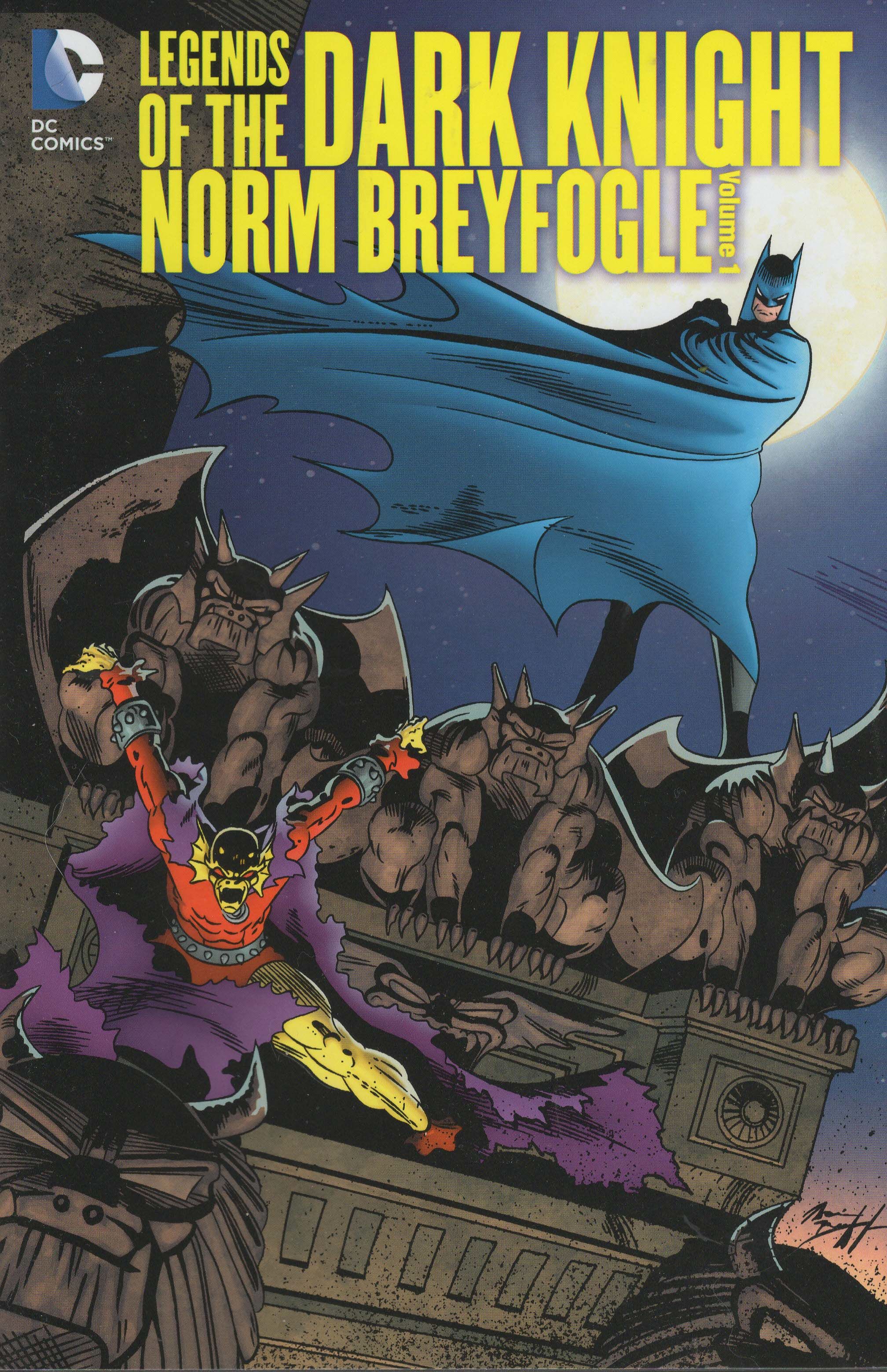

Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle volume 1 by Norm Breyfogle (artist) and a bunch of people who are not Norm Breyfogle. $49.99, 516 pgs, FC, DC.

I'm not going to write about this, because I already wrote about most of it, and the stories I didn't cover are generally good, although they're not written by Alan Grant so they're a notch below his work on the comic. Mike Barr's story about the Crime Doctor ('Tec #579) is solid, Max Allan Collins' love story from Batman Annual #11 shows Bats at perhaps his most douchiest (and given that it's Batman, that's saying a lot), 'Tec #582, by Jo Duffy, is a pretty terrible "Millennium" crossover issue, and the Jason Todd-centric story in Batman Annual #12 (written by Robert Greenberger) is a pretty great Jason Todd story, which, given how much DC seemed to hate Jason Todd (especially the post-"Crisis" version), is kind of amazing. But then Grant (and, for a little while, John Wagner) take over, and the magic begins. The real reason I'm pointing this out is because I imagine Breyfogle gets some of the money from the sales of this book (at least, I hope so), and considering that he's still recovering from a stroke, buying this not only puts a bunch of good comics in your hands, but maybe gets some money to a dude who desperately needs it. So check it out! You won't be disappointed!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆

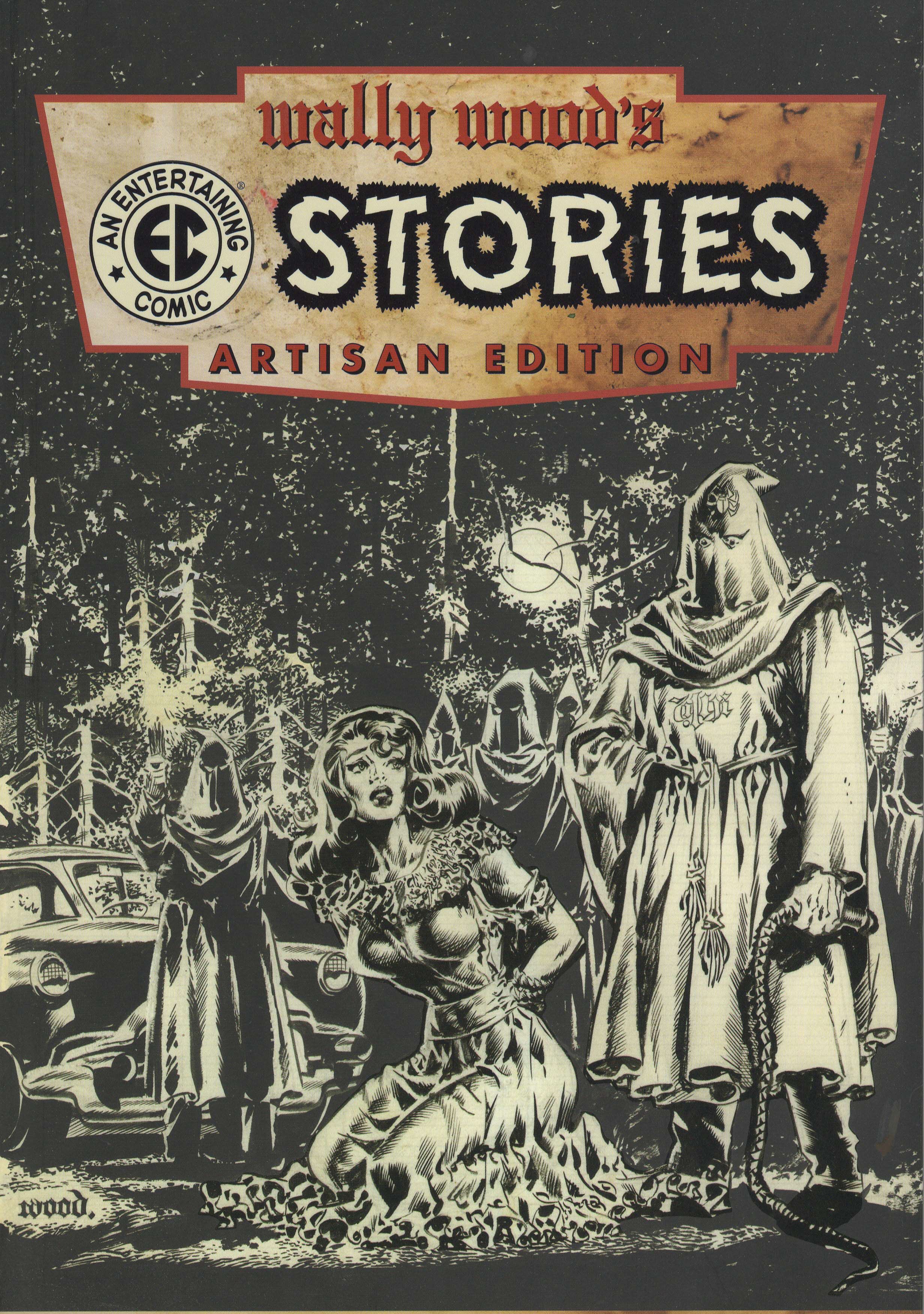

Wally Wood's EC Stories Artisan Edition by Otto Binder (writer), Ray Bradbury (writer), Al Feldstein (writer), Harvey Kurtzman (writer), and Wallace Wood (writer/artist). $49.99, 152 pgs, BW, IDW.

I don't have a lot to say about this collection - yes, it's 50 dollars, which is quite dear but totally worth it. I mean, it's Wood from the 1950s, when he first became great, and EC stories are always fun to read, as Feldstein and the others could churn out those groovy tales with twists like nobody's business. Wood's raw, unadulterated art is tremendous to look at, as he uses patches to "fix" some panels, a lot of gouache (which seems weird as many, if not all of these stories were colored, so I imagine the whiteness of the paint got lost a bit) and Zip-A-Tone, and beautiful grayscales in many places. His line work is tremendous, his monsters are creepy, his men are manly, and his women are stunning. He uses blacks really well, especially in the story about the atomic bomb falling on Hiroshima, where he uses big black blocks to show the people and buildings thrown into stark shadow by the flash of the explosion. It's just an amazing book, and really, any chance you get to buy comics featuring the classic artists of the past (like this one and the Toth one, above), you should take it! I featured some of the stories in this collection here, in case you want to check them out. Or you could just trust me and buy this book!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆

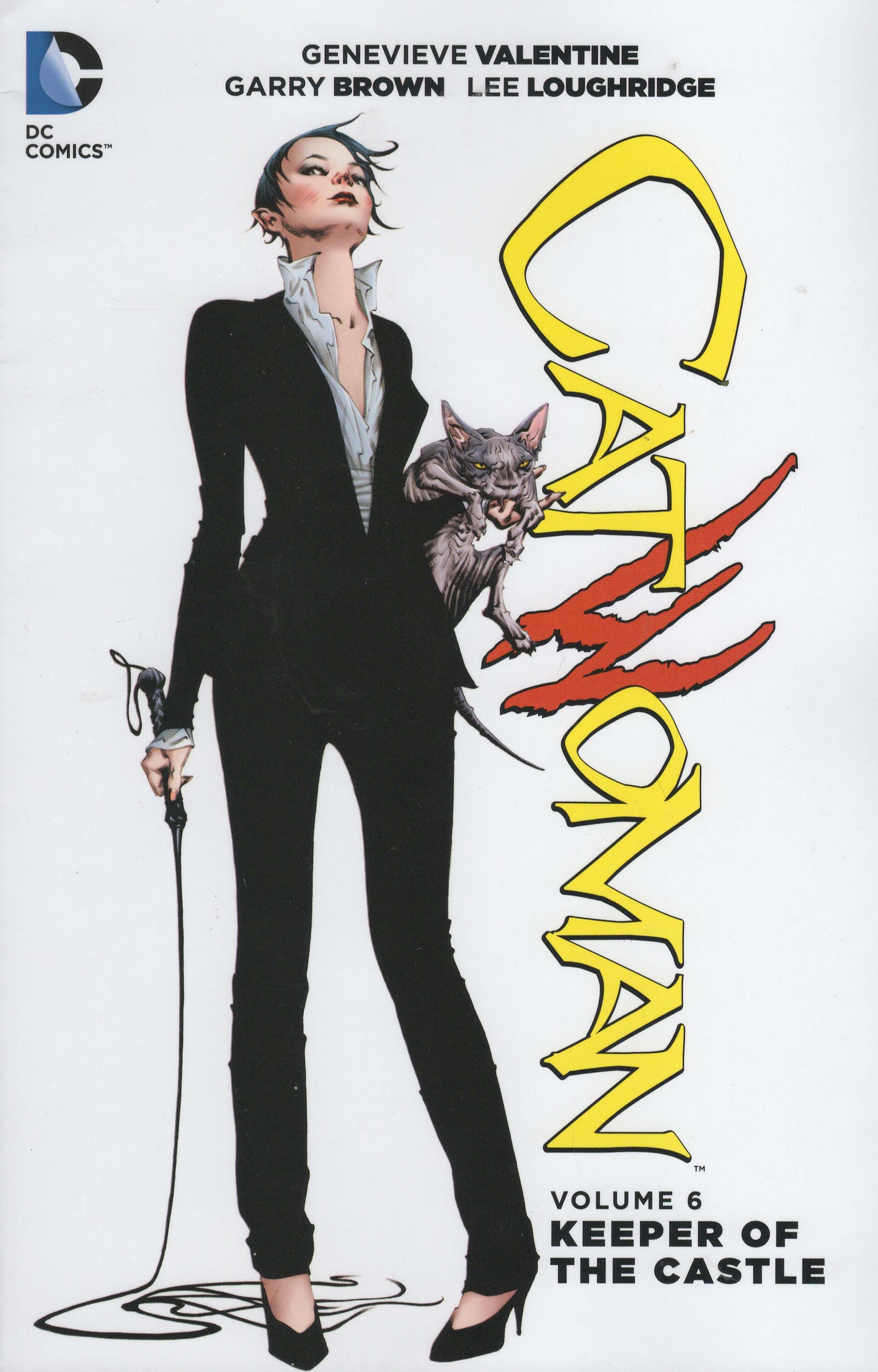

Catwoman volume 6: Keeper of the Castle by Garry Brown (artist), Sal Cipriano (letterer), Taylor Esposito (letterer), Travis Lanham (letterer), Lee Loughridge (colorist), Carlos M. Manguel (letterer), John McCrea (artist), Tom Nguyen (artist), Pat Oliffe (artist), Genevieve Valentine (writer), and Paul Santos (editor). $16.99, 158 pgs, FC, DC. Catwoman and Batman created by Bill Finger and Bob Kahn. Black Mask created by Doug Moench and Tom Mandrake.

I was very curious about the new direction of Catwoman, because it seems like a great idea to make her a crime boss - she's almost always been on the wrong side of the law, but she has also, in recent years, been very concerned about the state of Gotham, so having her as a crime boss who wants to turn down the internecine warfare in Gotham is a smart idea. I don't know if the previous writer set this up for Valentine, because she dives right in, as Selina is already the head of the Calabrese family at the beginning of this trade. Valentine also introduces a "new" Catwoman, who decides to take matters into her own hands because the real Catwoman is noticeably absent. Valentine moves fast, occasionally to her detriment, because it just seems like she sets up a lot and knocks it down, like the traitor within Selina's ranks, who is found out and dispensed with very quickly (in what is meant to be a fairly emotional scene, but lacks it because we just don't know the characters involved that well) or even the big plot, which is a lot of smoke and mirrors and seems to dissipate in an instant, even though Valentine is working a long con here, so there's plenty left to do. It's a strange comic - there's so much that works, and I love the idea, and if sales are good, Valentine could have a long story to tell, but she still seems to rush a bit too much. There's also the fact that Selina is a "good" criminal - she doesn't want to be involved in drugs or prostitution, but it begs the question of what kind of crime would she be involved in, then, as a crime boss? Valentine tends to gloss over what the crime families actually do - there's smuggling, of course, but surely the families have their hands in other pies as well?

Brown is a good artist for this kind of book (unfortunately, he's off the book now), as his scratchy, rough style fits the grungy, 1970s-indie-movie vibe Valentine is going for on the book. This is especially noticeable because in the middle of the book we find Catwoman Annual #2, which is about the new Catwoman and is not drawn by Brown. The three artists who work on it (Oliffe, Nguyen, and McCrea) are good, but they're much slicker (even McCrea, who's not really that slick), which makes it good that the comic is a bit more "superheroic" than the main story. Unfortunately, Brown gives us scruffy Batman, which is not a good look. Why do artists draw scruffy Batman? Batman shaves, dang it!

I'll probably check out the next trade of Valentine's run, because this is intriguing even with the flaws. It's a cool direction for Selina, which of course means DC will have to course-correct soon enough!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

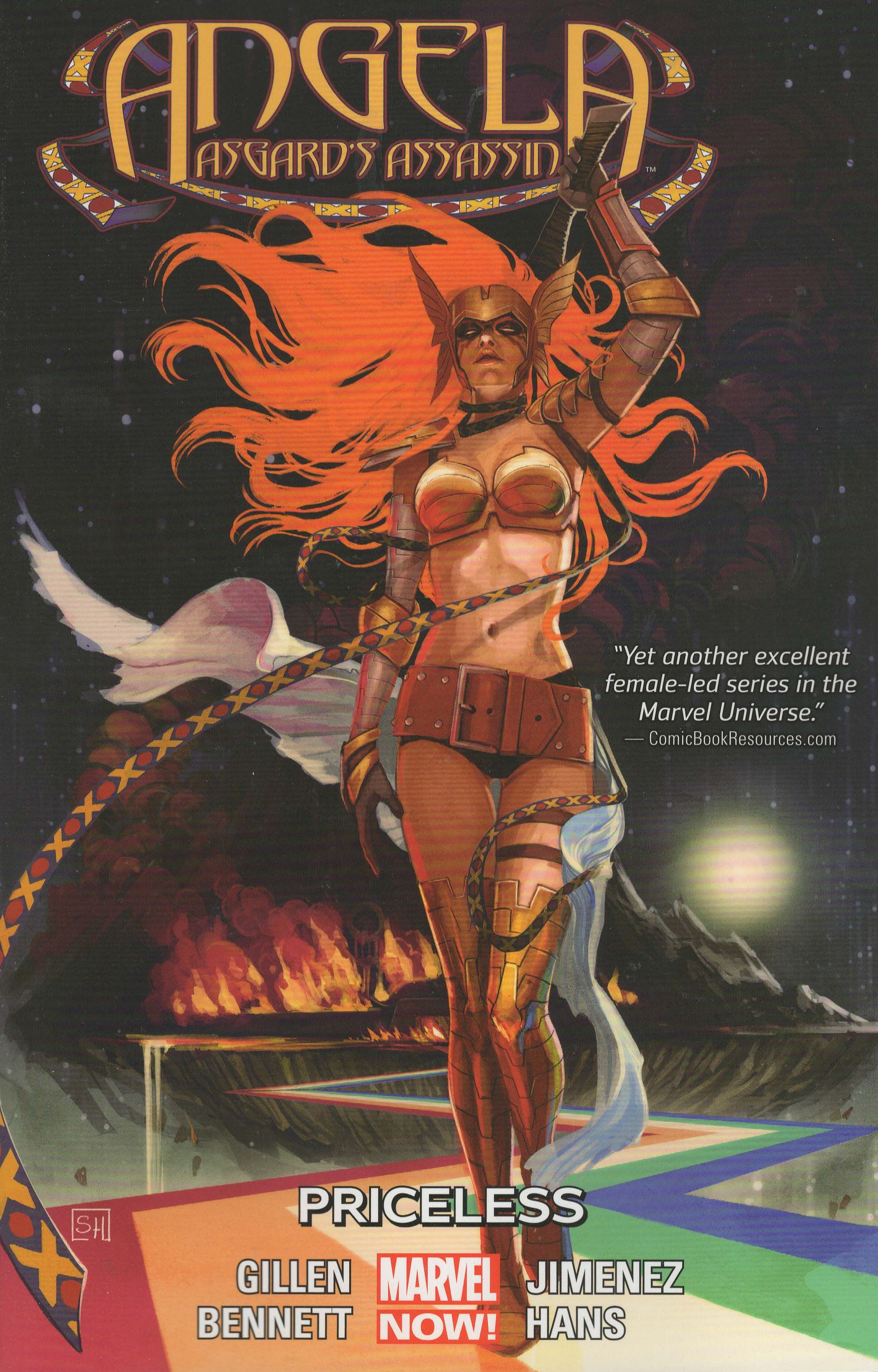

Angela: Asgard's Assassin volume 1: Priceless by Marguerite Bennett (writer), Clayton Cowles (letterer), Romulo Fajardo Jr. (colorist), Kieron Gillen (writer), Scott Hanna (inker), Stephanie Hans (artist), Phil Jimenez (penciler), Tom Palmer (inker), Le Beau Underwood (inker), Sarah Brunstad (assistant editor), and Jennifer Grünwald (collection editor). $17.99, 120 pgs, FC, Marvel. Angela created by Neil Gaiman and Todd McFarlane. Thor and Loki created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, and Jack Kirby. The Warriors Three, Odin, and Sif created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Freyja created by Stan Lee, Robert Bernstein, and Joe Sinnott. Star-Lord created by Steve Englehart and Steve Gan. Rocket Raccoon created by Bill Mantlo and Keith Giffen. Gamora created by Jim Starlin. Drax created by Mike Friedrich and Jim Starlin. Groot created by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Dick Ayers.

Angela is not a bad comic, although it's the worst example of a cliché of superhero comics, in which no one thinks to ask someone what they're doing or even, you know, notice the evil black tendrils seeping out of a baby's eyes, which might tell you the kid isn't exactly kosher. Angela kidnaps Odin and Freyja's baby and Thor and his groupies come after her, and there are all the hallmarks of a Gillen comic - very good dialogue, a bit spotty on the plotting - and it's all very exciting, but like far too many works of fiction (comics are not alone in this), it works only because far too many people are idiots. Thor is (naturally) an idiot, although he eventually gets all heroic on us. Even Angela is a bit idiotic, because she could have made life a lot easier for herself. It's a pretty good comic, but you really have to check your expectations for characters to act like regular people at the door. I do that all the time when I consume fiction (unfortunately, I kind of have to), so I didn't mind this. Page-by-page, it's a pretty exciting book with a lot going on, but when you step back and think about it, there are some holes. I mean, what's the deal with the kid who just wants her damned ball back? If Angela took my ball from me and demanded a trade for it back, I'd tell her to keep the fucking ball and take off. But this girl seems important, yet we never get back to her. Will she be back in the All-New, All-Different, But Totally Not a Reboot Marvel U.?

The book looks great, too. Jimenez is a great artist, and he's very good at stuff like this, so we get nice, stuffed pages of awesome action. In this brave new world of digital color muck, a clean penciler like Jimenez might be overwhelmed, but Fajardo does a good job with rendering so that he complements the line art very well. Hans is another superb artist, and her pages, which are generally flashbacks, are wonderful, too. Her work is dreamier than Jimenez's, which makes it a great fit for the flashbacks, and I'm pretty sure she colors her own stuff, and it's just different enough to provide a nice contrast to the "main" story. Jimenez gets to give Angela a new costume, too, which is good, as the McFarlane one was terrible. I still don't know if Angela was wearing pants or just that giant belt.

Bennett is going solo in the new series, so we'll see how that works out. This is a pretty good standalone story, though, so even if you don't want to continue with it, this is a nice tale of Asgard and Angela and scary babies and the Guardians of the Galaxy. Those are always keen!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

Conan volume 17: Shadows Over Kush by Michael Atiyeh (colorist), Jimmy Betancourt (letterer), Brian Ching (artist), Eduardo Francisco (artist), Richard Starkings (letterer), Fred van Lente (writer), Roxy Polk (assistant editor), Aaron Walker (assistant editor), and Dave Marshall (editor). $19.99, 148 pgs, FC, Dark Horse. Conan created by Robert E. Howard.

Van Lente begins his run on Conan with a story about our hero feeling bummed about Bêlit's death and then getting over it, as you figured he would. So he's drinking himself into a stupor, which many of us would do if we'd lost the great love of our lives, and is only shocked out of it when two dudes steal all his stuff, which is a really bad idea, and dump him in a pit, which is an ever worse idea. So Conan gets to do some killing, which I'm sure many people who have lost loved ones would want to do, but you don't live in the Hyborian Age, do you? Conan gets a job at the palace, of course, because he's such a good fighter (and so virile, although van Lente has fun showing us that Conan is actually not terribly happy to be doing the sex because the princess is totes evil). Van Lente does some nice work with the social aspects of Conan's universe, which other writers haven't really delved into, as the story takes place in Kush, where most of the people are dark-skinned but the rulers are slightly less so, so racism becomes a part of the story, even though van Lente doesn't push it too hard. He also makes the point about the guards over which Conan is placed, as they are seen as betrayers of their people by the oppressed, so they become tied to Conan simply because they have no homes to return to. If van Lente (or future writers) are moving Conan toward being a king, this might be the first place it starts.

I don't know what the art situation is on this comic, because Ching only does the first three issues before Francisco takes over. Ching's lines are a bit more angular and rougher, which fits Conan's world a bit better, while Francisco's art is perfectly fine but a bit smooth. I don't know if Ching is just slow, but it's too bad, as the big battle between Conan and the pig monster is a bit too slick for its brutality, and I think Ching would have made it a bit better looking. But both artists are fine, and Atiyeh is a good colorist, so he gives the book a slightly unified feeling to it (although part of why the fight doesn't look as good as it might is a slight over-rendering in the colors). Even Francisco's Conan is a bit too pretty, so while he still looks tough, he doesn't look like he's gone through as much as he has.

This is volume 17 of Dark Horse's Conan series, and I've bought them all, so obviously I think they're good. This is actually not a bad place to jump on, as van Lente gets us up to speed with his sad recent past and then throws a big single story at us, which sets him on a new path. So if you haven't checked out this massive series yet, (I think they're up to 80 issues?), this is not a bad place to dip your toe in the water.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Soon I Will Be Invincible by Austin Grossman. 279 pgs, Pantheon Books, 2007.

I'm fascinated by prose books about superheroes, because they're such a visual medium and comics do them so well, so when we don't have the benefit of pictures, it really makes me keen on seeing how authors deal with them. Grossman uses two characters and switches back and forth between them on a chapter-by-chapter basis, and both are written from a first-person point of view. The first is Doctor Impossible, the greatest super-villain in the world, who escapes from prison and comes up with a world-conquering scheme. The second is Fatale, a newer hero who joins the Champions, a super-group that is reconstituted when Impossible gets out. Looming over everything is the death of CoreFire, the greatest hero in the world and Impossible's nemesis. CoreFire died under mysterious circumstances, and everyone thinks Doctor Impossible did it, even though he knows he didn't. So we have the classic makings of a big old conflict, and of course it plays out in a secret lair on a tropical island. I mean, it would have to, wouldn't it?

The plot, ultimately, doesn't mean too much - like every superhero conflict, we know what's going to happen, and Impossible's fatalistic streak about his entire plan is one of the charms of the book. It's not even much of a mystery, as the heroes aren't terribly concerned with finding CoreFire's killer mainly because they believe Impossible did it. Instead, Grossman gives us origin stories, mainly Impossible's and Fatale's, but also many of the other heroes'. Impossible is a genius, and Grossman points out that geniuses have a hard time in the world, so of course many of them turn to villainy, and he also creates a boarding school where, it seems, many superpowered individuals came from, although Impossible can't explain why. Impossible had a hand in creating CoreFire - Impossible is a Lex Luthor/Dr. Doom hybrid, as CoreFire is clearly a Superman analog - but the hero doesn't remember him, and his burning desire for recognition is what drives him. When he defeats the Champions late in the book, he's unfulfilled because CoreFire isn't with them, so his victory over "lesser" heroes doesn't satisfy him. Meanwhile, Fatale is a cyborg, rebuilt after she was in a horrible car accident, and Grossman does a nice job with creating a mystery around her as she tries to prove herself to the more established heroes of the Champions and also track Impossible down. She befriends Lily, a reformed villain (and once Impossible's lover) who has also joined the Champions, and their outsider status on the team is the best part of the hero section of the book.

Grossman creates a bizarre world that, unlike the oblivious DC and Marvel universes, has a sense of its bizarreness, which is kind of neat, as Grossman mentions the strange gems and alien presences and supersoldier programs that create all of these superhumans. The weirdness of superheroes is one thing prose can do seemingly better than comics - in comics, so much of the weirdness is just accepted, while book authors tend to spend some time highlighting the weirdness. Books also have an advantage over comics in one way, and that's internal narration. While comics use internal narration, they can't use too much of it, as it's a visual medium and too many words clutter the pages. Grossman is very good with Fatale and the way she reacts to being the new member of the team - we've gotten that in comics many times, but it's often somewhat superficial, but in this book, Grossman doesn't have to worry about throwing in some nice action because there's no art. So Fatale can ruminate on her feelings as she meets the Champions for the first time and how she thinks she lets them down when she doesn't live up to what she thinks are their standards. Doctor Impossible is a far more sympathetic character than many mad scientist villains, not because we sympathize with his schemes but because his motives are so human and petty, and we don't often get that from supervillains in comics. The internal world of the characters is something that comics often skim over, but Grossman doesn't have to.

Of course, a big disadvantage of the book is that Grossman has to describe the action, and he doesn't always succeed completely. There's a scene where Impossible appears trapped by Mister Mystic - a Doctor Strange analog - but he gets out of it, and I can't figure out how. There's always the possibility that I'm not very bright, but the scene just isn't written very well. The big battle is better, but because it's described, it loses some of the grandeur we'd get if a great artist was drawing it. Doctor Impossible's grand scheme is fairly clever, but again, it loses some of the spectacle when it's just him talking about it. Grossman can make Fatale sound more gruesome than an artist would probably draw her, which is not a bad thing, but for some things, artwork really does help. There's a reason superhero stories are so popular in comics and, these days, movies.

Still, it's a fun read. Grossman takes superheroes seriously while still acknowledging the slightly ridiculous circumstances that would create them, and the result is a thriller that isn't so deadly serious as you might expect. Grossman is aware of the clichés of the genre and he uses them nicely, with the characters' internal narration often admitting them but still struggling against them. This is a somewhat self-aware superhero novel, but that's not the worst thing in the world. If you're a fan of superheroes, it's a neat book to check out.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Codex by Lev Grossman. 348 pgs, Harcourt Books, 2004.

Much like prose books about superheroes, I also dig books about books, whether those books are fictional or non-fiction. The best of the fiction books, I suppose, is The Name of the Rose, but I've read several over the years. I love the idea of people figuring out a mystery that leads to some hidden tome full of secret knowledge. So of course, when I came across Codex, I picked it up. Grossman introduces us to Edward Wozny, a young banker in New York, who is about to move to London for a new job when his boss asks him to visit one of their clients, an English duke and duchess. He meets them briefly (as they're leaving their apartment building as he enters, and he doesn't know it's them until later), and then their head secretary tells him his job: he's to look through crates of books that the family shipped over to New York during World War Two (to save them from destruction) and which have never been opened for a book that may or may not exist written in the fourteenth century. Edward thinks this is beneath him, but he slowly gets drawn into the search. He meets a girl (of course he does), Margaret Napier, who is studying the author, Gervase of Langford, and who tells him the book he's looking for is a well-known hoax from the 1700s. He also gets a video game from his best friend which sucks him in, as it's a world-building game that he doesn't quite know how to win and he ends up in a strange part of the game where the world basically ends. We know that these two parts of the book will intersect eventually, but Grossman does a nice job with that, as he takes his time, doesn't get too caught up in the virtual world, and the connection does make some sense. Edward has a bit of an obsessive personality, so when he decides that he will take on the job, Grossman does a good job showing how it makes sense to him, but also how it explains his obsession with the game, too. Margaret is an interesting character, too - she and Edward eventually hook up, but she's not a typical conquest, as she's difficult to work with, much smarter than Edward is, and focused on things that he can't understand completely (like obscure fourteenth-century writers). They have a nice relationship, as Edward doesn't look at her as a sexual object until much later in the book, and even then, it's something they both want briefly but know is probably not a good long-term idea. I never like people just having sex in fiction because they're a man and a woman (if they're both straight, of course), but Grossman does a decent job getting us there.

The mystery of the codex and what's in it and what it means is central to the book, of course, and Grossman does a good job with it. He does a bit too much expository stuff when Margaret tells Edward what's supposed to be in the codex, but his writing is fairly lively and he tries to break it up a little, so it's not too bad. He introduces some elements of danger, as it seems that more than just Edward (and Margaret, who gets sucked into his quest) are looking for the book, but for different reasons than he is. Obviously, in a book like this, you never know whom you can trust, and Edward is always looking over his shoulder and trying to figure out what's really going on. But the way he and Margaret unravel the mystery is very neat, and it all makes sense, which is kind of nice to see.

The problem with books of these sort is that the authors want to set them in the "real world," so things can't change too much. This means the books can never have the impact that they might, because we already know that they didn't. In The Name of the Rose, the book is destroyed (um, spoiler alert?). I'm not going to say what happens in this book, but while its stakes are a bit lower, Grossman still has to figure out a way to make sure that the codex doesn't become public. That's kind of annoying, because the end of the book is a bit more convoluted than the rest of the book - yes, even with a puzzle to solve and a virtual reality world to wander, the book never needs to jump through ridiculous hoops to get where Grossman wants it to go. At the end, it feels like he's doing that too much, and I'm not sure why. The book, as I noted, isn't quite as momentous as some books in other fictional stories of this nature, so Grossman could have gone a different way. It's weird.

Still, this is an entertaining book, full of interesting mysteries and fun (made-up) trivia about the 1300s and what Gervase was really doing. It's a quick read, even with all the twists and turns, and Grossman does a nice job with the characters. It's not a classic like Umberto Eco's book, but what is, right? If you're a bibliophile (and I have to imagine some of you are), it's a nice page-turner.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Latitude Zero: Tales of the Equator by Gianni Guadalupi and Antony Shugaar. 258 pgs, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2001.

This is a pretty neat book, as it's a quick read and it's full of wild stories about equatorial events. As the authors point out in the introduction: "The history of the world has almost always been written from a point of view situated around forty-five degrees north latitude." This is, of course, where Europe and the United States lie, and they point out that this Euro-centric (and white, they don't mention, but even though they mention Asia, it's still implied) has colored how we view history. This has changed in recent years, but it's still largely true, and even these authors don't escape it, as they focus on the equator, but how Europeans interact with the people of the equator. It's tough to write too much about life before the Europeans, especially in a short, somewhat breezy read like this, as the authors aren't terribly interested in delving into the cultures of equatorial people so much, so they don't get into serious historiography of the regions. They're using European sources - primary sources, to be sure, but still - and so the book will have a Euro-centric bent to it, even though they certainly don't ignore the indigenous people of South America, Africa, and South Asia/Oceania.

The book is split into those three sections, in that order, so we begin in South America (after a brief introduction that delves into medieval/early modern ideas about and explorations of the equatorial regions, including a few pages about the famous Chinese treasure fleet of the 15th century) with the Spanish conquistadors looking for El Dorado in the Amazon. The authors have a knack for turning everything - Gonzalo Pizarro's trek into the jungle, the French expedition to measure the earth - into an operatic epic, and this knack is the best part of the book, because each chapter feels like a mythic drama. The story of Jean Godin des Odonais, a Frenchman on the expedition to measure the earth who fell in love with a 13-year-old Creole who lived in a small Ecuadorian village is terrific. Godin had to leave his young bride after a few years to head down the Amazon to Cayenne, French Guiana, and it turned out he could never make it back, due to many issues, not the least of which was that the Spaniards believed he was a French spy and wouldn't let him head back inland. Almost 20 years after he left, his wife decided to navigate down the Amazon herself, and they were finally reunited. It's a great tale, full of intrigue, danger, romance, and the indomitable human spirit. The South American portion of the book concludes with a bizarre tale of Elisa von Wagner, an Austrian whose family lost their fortune in World War I, at which time she decided to travel Europe leeching off rich men. She ended up in the Galápagos Islands, where she went completely naked. There were other people on the small island, and Wagner took many men as lovers, including a 15-year-old boy. Things did not end well.

The African sections are mostly standard imperial tales about English explorers trying to find the source of the Nile and the horror of Leopold II's Congo, although the first chapter is about Kimpa Vita, who tried to found a new, African version of Christianity in the Kongo early in the 1700s. Yeah, that didn't end well, either. I always like reading about the African land grab in the 19th century, but I've read about it a lot, so this part didn't really tell me anything new. The third section, which focuses on Asia, tells about Magellan before a chapter about James Brooke, an Englishman who became a rajah in Brunei in the 1840s. The book ends with a very brief chapter on Krakatoa (something else I have read much about) and Robert Louis Stevenson's sojourn in the Gilbert Islands.

It's entertaining and quick to read, although the authors don't delve too far into each subject. There are no endnotes, and the bibliography isn't very big, but as a primer on some of the great explorations and colorful characters who have wandered in the equatorial regions, it's a good book. I wish it had been more in-depth, but such is life!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

Meditations on Middle-Earth, edited by Karen Haber. 235 pgs, St. Martin's Press, 2001.

I've been on a bit of a Tolkien jag recently - earlier this year, I read a book about his experiences during World War I, and more recently I read a pretty standard biography, and now this, which brings together 17 fantasy/sci-fi creators for essays about Tolkien and what he meant to them. It's not a very good book, unfortunately. There are some gems - Ursula K. LeGuin's essay about rhythmic language in The Lord of the Rings is fascinating, Terri Windling's essay about fairies and the changing perception of them is neat, and Glenn Hurdling's interview with Greg and Tim Hildebrandt about how they became fantasy artists thanks to Tolkien is excellent - but overall, this is a dud of a book. The other essays, no matter the ostensible subject matter, fall into a general defensiveness about fantasy writing (even though the writers claim Tolkien made it "respectable") and how Tolkien saved each of them from their miserable existences. There's an animus toward critical reading of the book and how critics can't bring in outside influences and that the book exists in kind of a vacuum, which is both ridiculous and insulting and even though several writers mention the First World War as having a big influence on Tolkien and others bringing up his deep Catholicism. So which is it? Can the book be read critically, or can it not? Any text can be critically examined, yet these writers - perhaps reflecting their own prejudices against those who don't create, just review - take some pleasure in the fact that "critics" never liked Tolkien (at least in the 1960s and 1970s, although a few of them even mention "recent" surveys, that is, leading up to 2001) yet TLotR keeps showing up high on lists of favorite books by the salt-of-the-earth public. This might be an interesting topic for one essay, but it becomes interminable when so many do it, especially because so many of the essayists repeat other similar things - their lives were hard, they didn't know about fantasy because it was disreputable, Tolkien came into their lives during their early teen years and immediately made them all want to write fantasy. That's great, but it doesn't really make for interesting reading. Each of them tries to come up with their own spin on Tolkien, but when so many of them point out that Tolkien can't be critically examined, what are they going to do? That's why the Hildebrandts' experience is so interesting - they're the only artists in the book. That's why LeGuin's essay is so enlightening, because she doesn't make it personal. There are bits and pieces of interesting stuff in every essay, but for the most part, they are too similar to each other to be all that useful. It's great that Tolkien meant so much to all of the writers. But perhaps they could delve a little more deeply?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

King Solomon's Mines by H. Rider Haggard. 209 pgs, Barnes & Noble Books, 2004 (originally published in 1885).

In my continuing efforts to read books most people have already read, we come to King Solomon's Mines, which was Haggard's first success and such a runaway bestseller that he was able to live off of it for the rest of his life!!!! I had never read Haggard, but this is a fun book - it's a page-turner, very readable, exciting, tense, and well-written. I was expecting racism, and while the introduction gets into a bit, there wasn't as much as I thought there would be. Haggard's Alan Quatermain does stereotype often, but he does it for every group, which was very common back then, and while I haven't counted them up, his references to the good qualities of individual Africans seem to outweigh the stereotypical descriptions. He praises Ignosi and Infadoos all the time, and when he criticizes Twala, for instance, it's more because of his personal qualities than his membership in a race (although that does come up, unfortunately). Haggard cleverly puts two of the more egregious examples of racism in Africans' mouths - Ignosi speaks of Africans' propensity for violence, while Foulata expresses concern about mixed race romance ... but even that second example is still something that many members of all races still have trouble with today, so she's not that far off what many people think. All in all, this was less racist than I expected, and I wonder if it's endured as a classic partly because of that. I imagine many books written at this time were very racist, but they have been forgotten over the years, while readers can forgive Haggard's prejudices because they're not overwhelming.

Either way, it's a fine book. Quatermain is an interesting narrator because he's not the hero - Sir Henry is - and he goes out of his way to claim he's not brave or even particularly adventurous, and he proves it throughout the book. Most of the good things he does he does solely because he has no other option, while Sir Henry and John Good are the models of English-Victorian dash and vigor. Haggard, who spent some time in Africa, doesn't linger too long on descriptive passages about the land, but when he does, it's very well done, and we get a good sense of the exotic and alien nature of the land. The action scenes are really well done, as Haggard is able to make it intimate, so that we worry about the principals (I seriously thought Infadoos was dead meat in the final battle) but we also get a sense of the grand scope of things. And the battle between Sir Henry and Twala is very nicely written. Of course, like most treasure quests, there's an ironic twist at the end, but it's unfortunately the one we see too often in these kinds of stories, and I wonder if it was already a cliché when Haggard used it. No big deal, though - in most cases, it's the journey that counts, and once the explorers reach Kukuanaland, their quest becomes secondary to the human drama unfolding there.

King Solomon's Mines is very much a boys' own adventure - there are two women in it, and one of them is evil and the other is there to fawn over one of the Englishmen - but it's a good read for an afternoon or two, because it doesn't take long to get through it. It's pretty neat.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Well, holy crap, that's a lot of stuff, and only the last two trades actually came out in August! I'm getting way too slow with this stuff, so I apologize. I just read too many comics!!!!