As I'm getting more and more things in trade these days and many of those don't come out very quickly, I often miss titles that everyone is raving about for my year-end lists (see: Daredevil). So I've decided to do a post every month about the various trade paperbacks I got in the month. I've also included editions of things that may be from an earlier year but which I didn't get until now or which have been re-released, and some other stuff, too. I'm still going to review new graphic novels individually, but this is for anything that doesn't fall into that category. Sound good? Great. Let's check some stuff out!

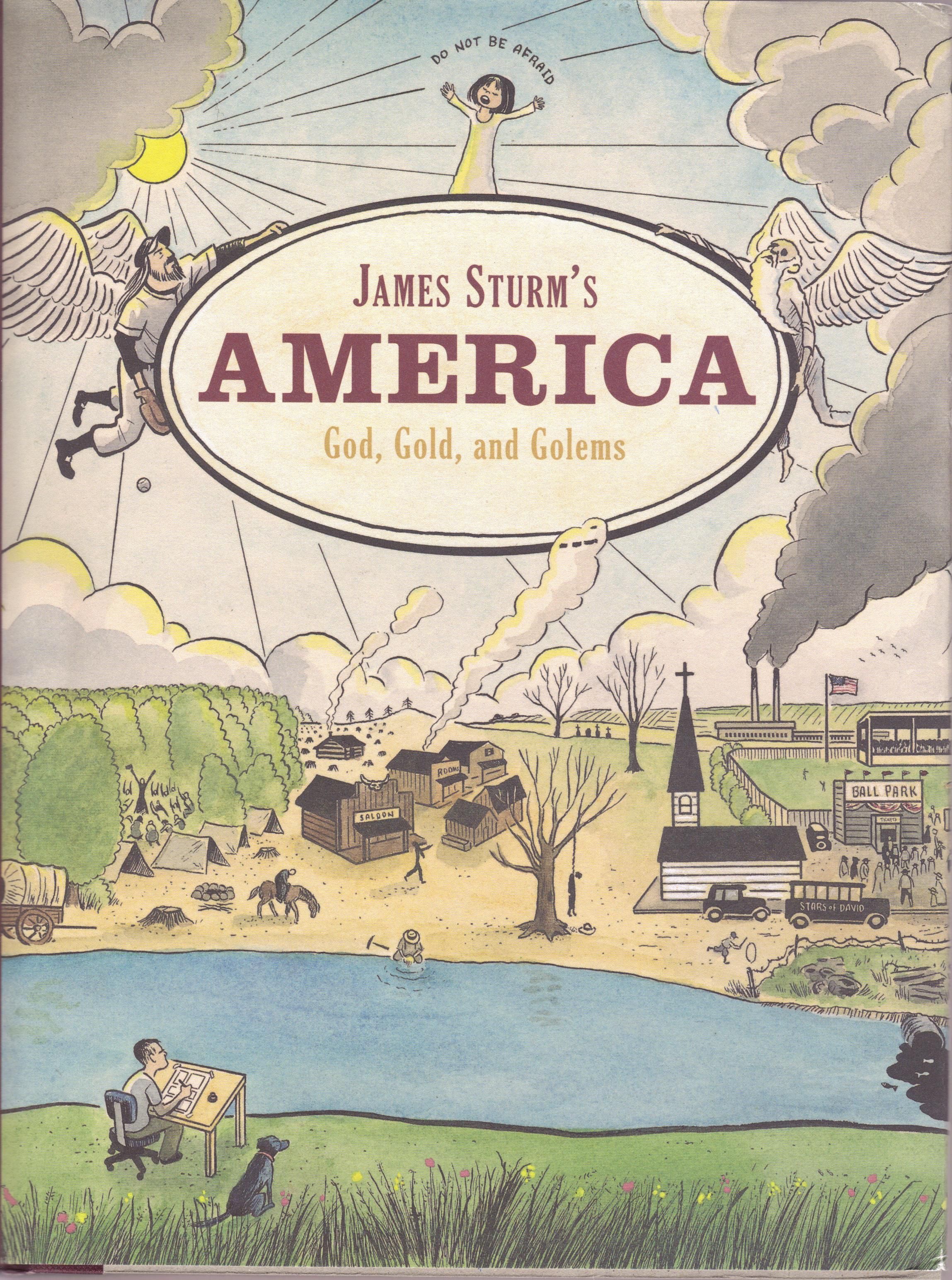

America: God, Gold, and Golems by James Sturm (writer/artist). $24.95, 186 pgs, BW, Drawn & Quarterly.

Almost two years ago, I reviewed James Sturm's Market Day, which I liked. Somewhere along the line someone told me I would like America, which was originally published in 2007. So when D & Q reprinted it, I picked it up!

Unfortunately, it's not as good as Market Day. Both comics are concerned less with plot than with naturalistic scenarios and delving into characters, but Market Day, perhaps because Sturm wrote it later, feels more assured and less polemic (even though, as I argued in my review, I think it is a polemic). America, which is divided into three chapters, seems to have both less and more on its mind, which sounds contradictory, I know, but is the way the book feels: Sturm seems to want to make points about American history as viewed through a non-traditional lens but he also wants to downplay those points so much as to make them almost inert. This isn't as big a problem in the final chapter, "The Golem's Mighty Swing" (although that chapter does have its problems, it's by far the best section of the book), but it makes the first two chapters somewhat of a slog to get through.

The first chapter, "Revival," takes place in 1801 in eastern Kentucky, where a family has arrived from Ohio to hear a great preacher. The wife, Sarah, seems much more invested in the meeting than the husband, Joseph, but he gets into the spirit of it when he arrives. They have a very specific reason for coming to the meeting - their daughter died on the road and they want the preacher to bring her back to life. I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say that they're going to be disappointed.

The second story, "Hundreds of Feet Below Daylight," takes place in Idaho in 1886. At a gold mine, several people vie for dominance, including the owner of the mine, which seems to have been tapped out. The characters are largely driven by greed, and the only one who appears to be pure, a girl named Althea, is the one who triumphs in the end, through no real agency of her own.

These two stories seem to be commenting on uniquely American traditions - the evangelical movement, which we think of as strong in this century but was nothing like the early nineteenth century, when it flourished in this country; and the frontier culture, which was lawless and ramshackle but promised fortunes for the bold and fearless. Sturm wisely doesn't allow any politics to enter into his narrative - there's no overt denigration of the religious fervor displayed in the first story, and while the men in Idaho tend to be vile, Sturm also makes it clear that they're living on the margins and need to survive. But Sturm also leaves out the narrative and even characterization, so that what we get is a basic snapshot of a time, and we never get to know the characters all that well and therefore their fates don't matter. We feel about the same for Althea, whose story ends somewhat happily, as we do about Sarah and Joseph, whose story is defined by tragedy. Sturm is simply presenting these episodes as examples of history, but without context, they're meaningless, and as narratives, they provide very little. "Hundreds of Feet" at least has a narrative arc, but it's unclear what Sturm is trying to do in the story.

"The Golem's Mighty Swing" has some of the same problems, but it's still much better than the other two stories. "The Revival" is slightly over 20 pages long, "Hundreds of Feet Below Daylight" is a little over 40 pages, while "The Golem's Mighty Swing" is 90 pages, so Sturm obviously has some more room to work with, and he gives us a fairly interesting narrative and commentary on American society even though he deliberately tries to be as naturalistic as possible. The story takes place in 1922 and features a traveling baseball team of Jews who barnstorm across the country playing local teams. They're quite good, but they still struggle to make ends meet, until one day a talent agent suggests that they make the team more entertaining by "creating a Golem" - their clean-up hitter, "Hershl" (really Henry) is a giant black dude who's obviously a ringer but who could pass for a Golem if they dress him up. The manager, Noah, wants nothing to do with the idea - he's more interested in baseball as a game than as a sideshow - but, of course, economic necessity forces his hand. And, of course, things go horribly wrong.

The reason this works better than the other two stories is that Sturm does have a solid narrative - the team travels around, playing ball and trying to make a living - and that narrative dovetails nicely with an aspect of American history, namely racism. Sturm shows us the complicated nature of racism in America without hammering us over the head with it - the Jews are treated like second-class citizens, sure, but they're also a draw because they're good at a classic all-American game, plus Sturm shows that not everyone feels this way about them. Henry is an interesting character, because unlike Jewish players, he was banned from the major leagues, so the fact that he's so talented but never gets a chance to star at the highest level is a tragedy, even though Sturm never mentions it. Prejudice rears its ugly head, of course, but what makes the book so fascinating is that by dressing Henry up as the Golem, Noah and his team are actively participating in the stereotyping, and Sturm asks us to consider whether they are at all complicit in what happens. Unlike the previous two stories, "Mighty Swing" is a complex story that does delve into American society without being too obvious about it, all while providing an interesting story. Sturm's pointless epilogue means the story ends on an oddly out-of-sync note, but the actual story is very interesting.

I haven't written about Sturm's art, but it's rougher and less detailed than his current work even as we can see it evolving. Whether by design or happy accident, his style seems to fit the stories - "The Revival" features almost primitive art, linking it to the primal forces at work in the Kentucky woods, "Hundreds of Feet" has smoother lines but Sturm also uses heavy inks to blacken the men and the surroundings, befitting a story about mines, while "Mighty Swing" shows a more confident hand and more precise lines as America moves into a more clean-cut Jazz Age. It's a nice mix of artistic styles, and I do hope it was planned.

America is an interesting comic, to be sure, but it's not as complex and thoughtful as Market Day. It's always nice to see stories about the marginalized in American history, and Sturm does try to ground the book in historical fact, so for that, America is a nice addition to a library. I just wish Sturm had been a bit more ambitious with it.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

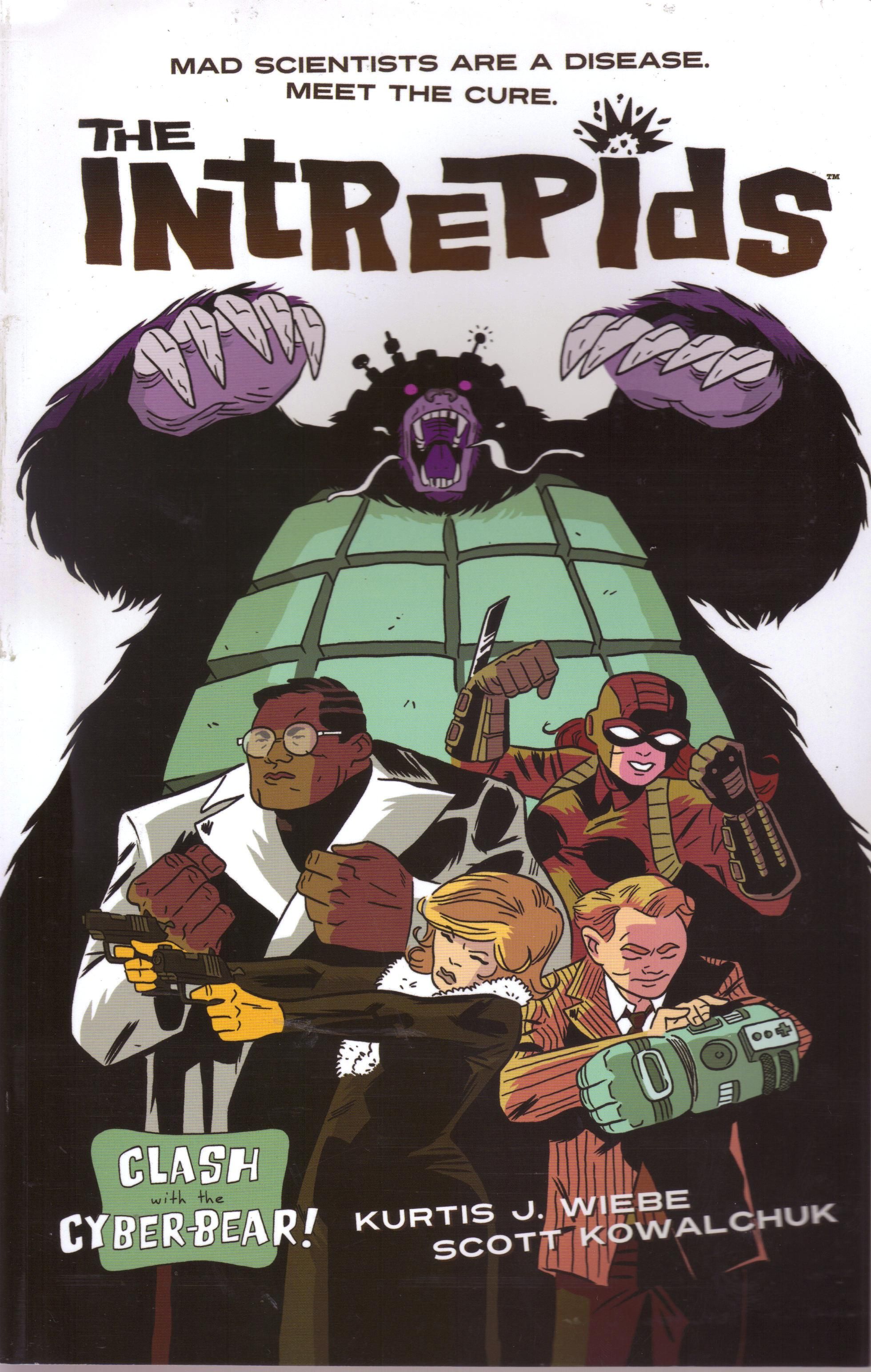

The Intrepids volume 1 by Kurtis Wiebe (writer), Scott Kowalchuk (artist), Donna Gregory (colorist), Justin Scott (colorist), Ariana Maher (letterer), and Frank Zigarelli (letterer). $16.99, 129 pgs, FC, Image.

The Intrepids is a six-issue mini-series about a group of teenagers (although none of them really look like teenagers) who, for various reasons, have no one to take care of them. Because no government agencies exist in comic-book worlds, a kindly scientist takes them under his wing and turns them into a team of super-heroes who fight "mad" scientists who are doing horrific experiments and trying to take over the world. You know, standard stuff. The team is: Crystal Crow, the main character, a crack shot and the first one "recruited" by Dante, the scientist; Doyle, the strong guy; Rose, the acrobatic assassin; and Chester, the computer geek. After an introductory mission (during which the team fights a cybernetically-enhanced bear, as seen on the cover), Dante decides they're ready to hunt down his arch-enemy, Professor Koi. Dum dum DUMMMMM!!!!!!

The team begins to track down Koi, all the while learning more about Dante's relationship with him and why Dante considers him so evil. They find him, of course, and of course they learn that the solutions are never as simple as they want them to be. Koi and Dante's relationship is more complicated than simple evil-vs.-good, and the team needs to figure out how to deal with all the knowledge they eventually gain. And, of course, this leads to a final big battle. Of course it does!

I wasn't too impressed with The Intrepids, unfortunately. It was mildly entertaining, but it feels like Wiebe is trying too hard to make it kewl, and he doesn't really succeed. I mean, we get the cyber-bear, we get a bunch of trained baboons, we get a robotic squid, we get a cyborg, we get experiments to turn people into superhumans, and it all feels like Wiebe is just putting these things in the story just for the hell of it - "Look how keen THIS is!" it seems to say. We get a minimum of characterization, as the characters remain either ciphers or stereotypes, and even something like Crystal finding her father doesn't have any emotional resonance because we know so little about her. I don't mind that lack in some books, because some books are just meant to be pure plot, but the plot of The Intrepids is too familiar for that. The big twist is obvious from about halfway through the first issue, and as I'm someone who rarely figures out the "big twist," that's saying something. There's a lot of AWESOME in this comic, but when you get that strung together without anything beneath it, it's kind of hollow. Wiebe isn't a bad writer by any means - Green Wake is quite good - but The Intrepids isn't his best work.

Kowalchuk is in kind of the same boat. His work isn't bad, in a vague, Paul Gristian kind of way, but like the script, it seems sloppy occasionally. He's called upon to draw a lot of kewl stuff, and he does it, but very little is really inspiring. The best parts of the books are his nicely-designed covers, which is nice when the book's on the shelf but doesn't much for the story. As I pointed out, none of the kids look like teenagers, which isn't too big of a problem except part of the hook of the book is that they're scared orphans that need a mentor to guide them. The fact that Kowalchuk bases the characters on celebrities isn't too bothersome (it's not like he uses photo referencing - they're just drawn similarly) except for Professor Koi, who looks far too much like 1970s Leonard Nimoy, and the fact that he bases Crystal on Faye Dunaway, so we get a panel of Crystal climbing down a ladder wearing a somewhat tight dress and high heels. I can suspend my disbelief a bit, but that bugged me. Kowalchuk is another creator who you can tell can do good work, but this isn't it.

The Intrepids is a sloppy comic in other ways, too. At one point Crystal fires a gun with a suppressor attached and the sound effect is a "bang!" There are spelling mistakes throughout ("who's" for "whose" and "reciever" instead of "receiver," for instance). I know that doesn't bother many people these days, but it should, because it's just unprofessional and it really does make the book less enjoyable. Well, for me, at least.

I get that Wiebe and Kowalchuk were trying to make a fun, pulpy comic with a lot of cool things, but that's harder than it looks and it takes more than simply thinking "What if baboons attacked the team? Wouldn't that be cool?" Well, maybe, but not necessarily. I'm just not a big fan of this comic. Oh well.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

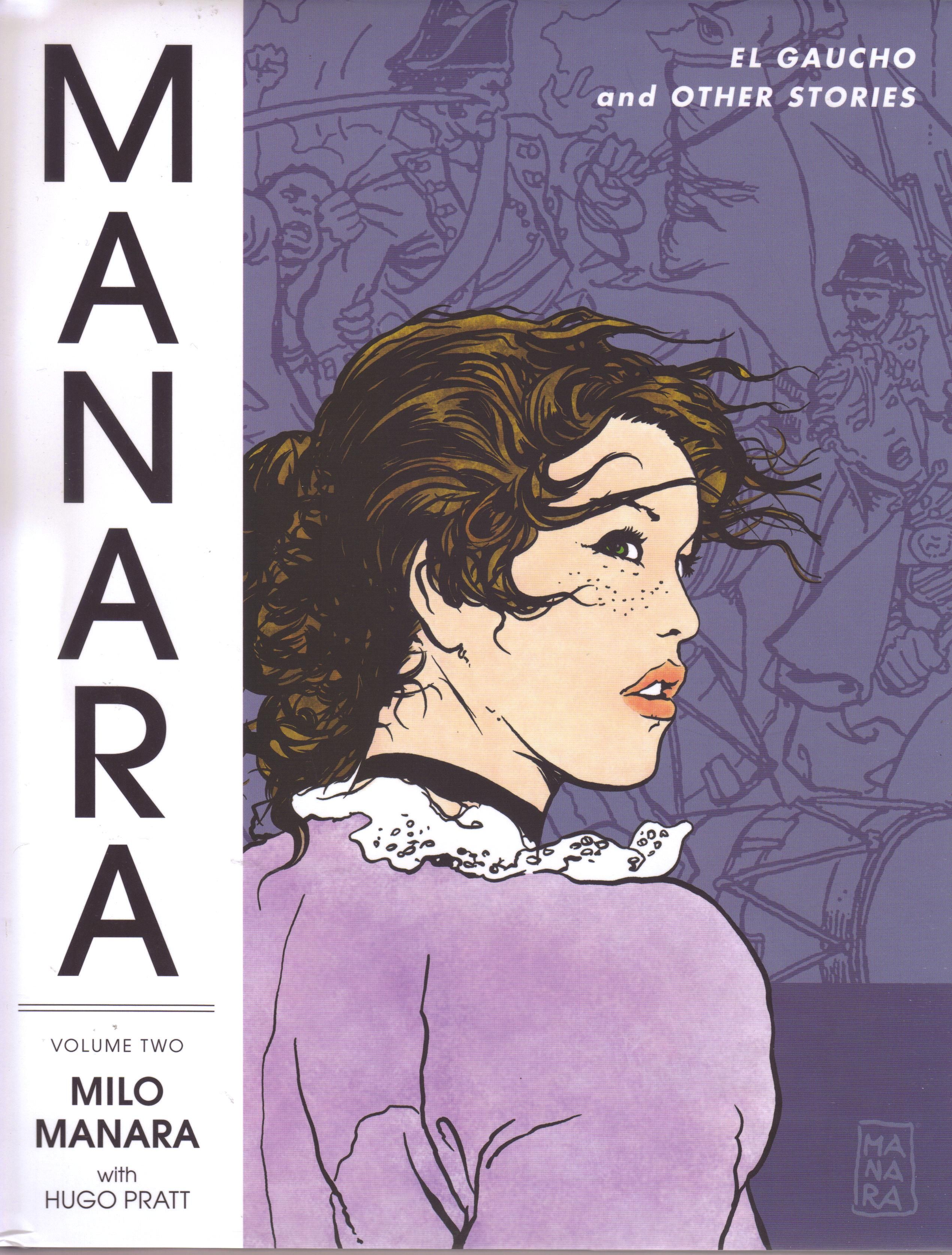

The Manara Library volume 2: El Gaucho and Other Stories by Milo Manara (artist), Hugo Pratt (writer, "El Gaucho"), Mino Milani (writer, "Trial by Jury"), Laura Battaglia (colorist, "El Gaucho"), Kim Thompson (translator), Tom Orzechowski (letterer), and Lois Buhalis (letterer). $59.99, 280 pgs, FC, Dark Horse.

I've always like Milo Manara's art, so when Dark Horse announced they were releasing his European comics in hardcover format, I thought I'd give it a try. The biggest problem I have with Manara is that he's not the best writer, and a lot of what I've read he wrote himself, so it wasn't great in terms of story but it worked well in terms of artwork. These collections, however, wouldn't only feature his own writing, but his collaborations, so that was good for me!

The first volume collected "Indian Summer," written by Hugo Pratt, and "The Paper Man," which Manara wrote himself. It was my first experience with Pratt, and I didn't like it. The story was packed with stereotypes, from the rapey Indians to the rapey clergymen - Pratt was apparently a fan of James Fenimore Cooper, but Cooper could get away with stereotypes back in the day, and Pratt should have known better. As wonderful as the art was, the reproduction wasn't great, and for 60 bucks, it's a bit annoying. Volume 2 was solicited before volume 1 came out, but I probably would have ordered it anyway because I didn't want one bad story to affect my enjoyment of the artwork, and people speak very highly of Pratt, so I figured I could give this one a try.

Dark Horse still hasn't solved the reproduction problem, unfortunately. I'm not versed enough in the coloring processes used and the reproduction processes, but about 90% of the way into "El Gaucho," the colors suddenly become duller and everything looks washed out (it happens very noticeably on page 118). The coloring before that was vibrant and dynamic, and there doesn't seem to be any reason for the abrupt change. The change is annoying because Manara's art, while fine in black and white, really comes to life in color, and the effect on the story is somewhat unfortunate. Like I mentioned, I'm not sure where the problem lies - if it's in the original comics (the story was serialized over three years in the 1990s, so maybe something happened to the paper or the coloring process while it was coming out) or if it's in the way Dark Horse reproduces it, but it's annoying.

"El Gaucho" is a far superior story to "Indian Summer," which is nice. Pratt begins in the late 1800s with a group of Spanish soldiers visiting an Indian encampment in Argentina, where they meet an old man who turns out to be a white man. He's actually a British drummer named Tom Browne who arrived in 1806 when the English invaded Buenos Aires. He tells his story as we flash back to those days. Pratt does a very good job providing the historical context without overwhelming the reader with it, and he gives us several interesting characters, including Browne, who's attached to the Highland 71st Infantry; Matthew, a hunchback on board one of the English ships; Clagg, the quartermaster of one of the ships; and Molly, an Irish girl brought along, with several other females, for the sailors and soldiers to use for sex. Pratt develops these characters against the backdrop of the invasion, as Tom and the others end up on the mainland as either prisoners of the Spanish or deserters from the ship. Pratt also does a very nice job creating a love triangle between Tom, Matthew, and Molly and all the consequences of that. Part of the reason that this story is better than "Indian Summer" is that Pratt takes time to make these characters interesting, so that even when they behave poorly, we understand why they act that way. The nudity also feels less titillating, which was an uncomfortable aspect (for me, at least) of "Indian Summer." Manara certainly doesn't shy away from nudity, but it also feels less like a puerile tale.

The second section is a series of shorts called "Trial by Jury," in which Milani and Manara present various figures from history and put them on trial. It's an interesting experiment that doesn't quite work perfectly (mainly because it's impossible to present such depth as would be needed to fully examine the actions of the figures in such a short space), but it does show Manara's earlier work, when his art was much rougher and less sensual than it would become. If we look at "El Gaucho," the details and the lushness of the lines makes the book feel sexual even when it's not, and it's an aspect of Manara's work that, it seems, gets criticized more often, even though that's kind of silly. In "Trial by Jury," we can see the evolution of the artist's style even though the stories are far from sexy. Most of them are in black and white, and it's because of this that I think his work is better suited to color. Even some of his later stories that I've read in black and white don't pop quite as nicely as his colored work.

Volume 2 of this series is better than Volume 1, but I'm still not sure it's worth 60 dollars. I'm much less skittish about spending that much for something that is more of a historical document about comics, which this is, but I certainly understand why someone would be reluctant to pull the trigger, especially if the content isn't up to snuff. I would certainly be more willing to spend it on this volume, though. Dark Horse's next volume is one of erotic tales, which I think I'll skip, but I'm curious to see subsequent volumes of Manara's work. The dude can draw, certainly!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

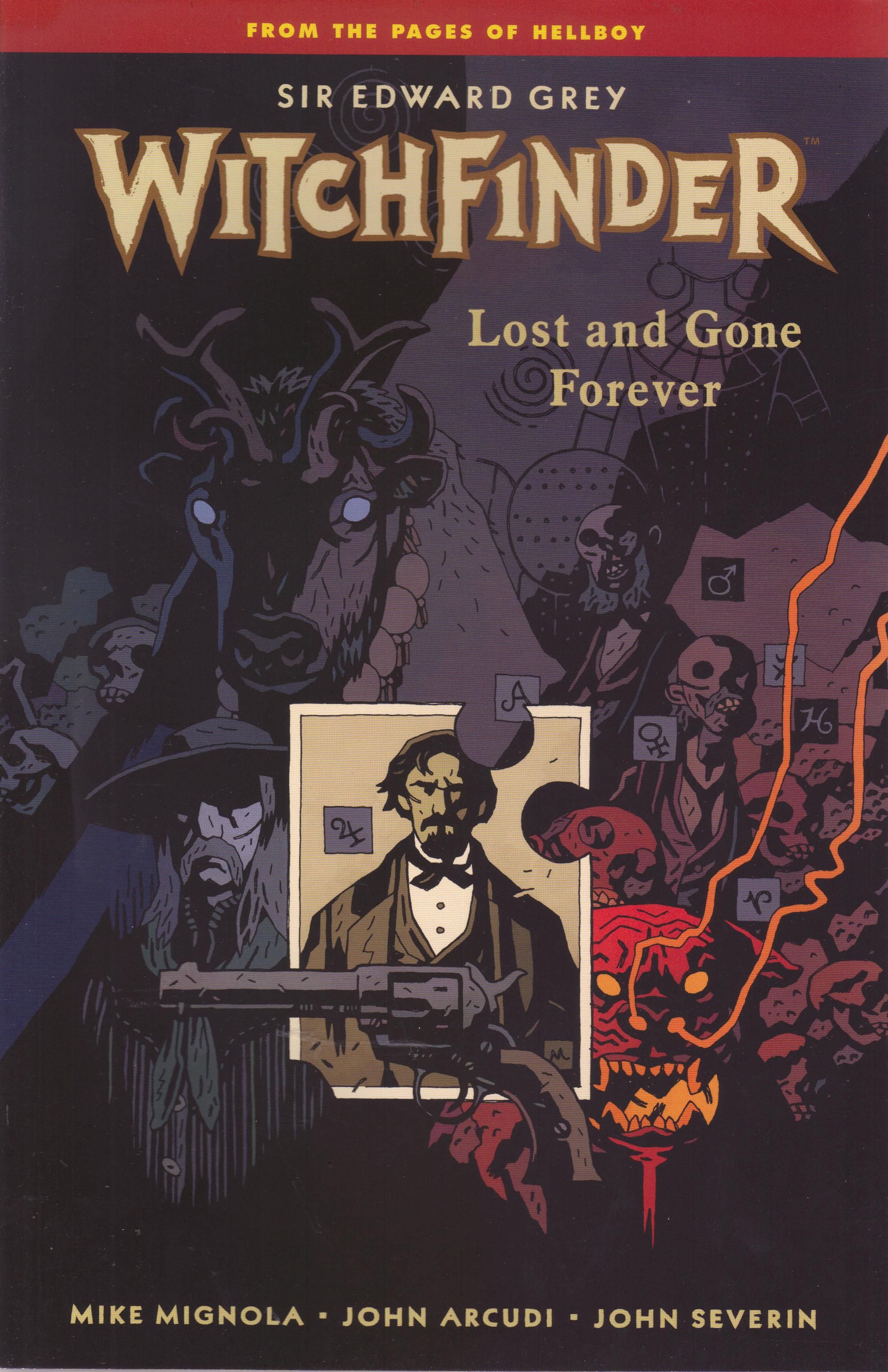

Sir Edward Grey, Witchfinder volume 2: Lost and Gone Forever by Mike Mignola (writer), John Arcudi (writer), John Severin (artist), Dave Stewart (colorist), and Clem Robins (letterer). $17.99, 109 pgs, FC, Dark Horse.

I guess I shouldn't call Mignola the writer - he and Arcudi came up with the story, and then Arcudi went off and wrote it. But oh well. It's Mignola's character, so that's good enough!

You don't need to read the first volume of Witchfinder to read the second one - they're fairly self-contained stories - because Arcudi gives us the basics: Sir Edward Grey is in service to Queen Victoria (the book takes place in 1880) and he's come to Utah to seek out a man named Lord Glaren. We also learn a bit more of his "origin" than we learned in the first book, and that he, you know, finds witches. It's right there in the name! Basically, it's a fish-out-of-water Western - Sir Edward is a proper English gentleman out in the rough part of the world, and he gets caught up in a supernatural thriller that has very little to do with Lord Glaren, who's mostly a MacGuffin. Arcudi writes that he wanted to do a Western in the B.P.R.D. universe, Mignola offered to let him use Sir Edward, and when John Severin said he was interested in drawing it, Arcudi decided that working with a legend was a good idea. Onward!

The plot is pretty typical, which doesn't mean it's bad. Sir Edward discovers that a witch is somehow using spirits of the dead to animate corpses and give her power, and she's tricking some Paiute Indians into helping her. Sir Edward falls in with Morgan Kaler, a mustached dude who wears a lot of fringes and has some special talents of his own. The two of them, with the help of Isaac, a man with some issues (he's somehow mentally deficient, but he's also older than he appears), fight the witch. And there you have it!

The plot really doesn't matter, mainly because Arcudi does a nice job giving us a good relationship between Sir Edward and Kaler, who appear very different at first but realize how similar they are as they work together. Kaler helps Sir Edward realize that his disdain for the non-Christian religions of the world is simply bigotry - one of the traits of Sir Edward is that he's a staunch Christian who uses the power of God to battle evil, but in Utah, he realizes that some things he thinks are evil might not be, really. It's not exactly a huge revelation, but Arcudi has made Sir Edward an interesting character - compassionate yet rigid - so any change in him is fascinating. As the plot unfolds, it's more compelling to read as the two characters begin to understand that things are not always as they seem.

Severin is a big draw, too, of course. I'm not quite as enamored with him as others, but he has a good, meat-and-potatoes style that works well in the no-nonsense world of Westerns (which is perhaps why he's drawn so many of them). He draws rough men and women very well, showing all the scars and creases that hard living creates, and he comes up with very distinctive looking characters - these are people we can imagine living on the frontier. The roughness of his pencils lends a solidity to the beasties that roam the hills, from the re-animated corpses to the nasty dog-thing living in a cave. The very few times his art doesn't work as well is when he needs to draw something a bit more ethereal - his art just isn't suited for that. But luckily, he doesn't need to do that all that often. It's not a stunningly beautiful comic, but it feels like a Western, which is a very good thing.

Like a lot of the Hellboy-verse, I'm not sure if this comic will convert people who just aren't into horror. Maybe, but they seem to be just good, solid horror stories for people who dig the genre. I imagine some people like this because they like Severin or because they like Westerns, and it's a pretty good example of that genre and the art is nice. I liked it, but I'm not sure it will convert anyone.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆

Jinn by Matthew B. J. Delaney. 548 pgs, St. Martin's Griffin, 2003.

I also figured I'd review the prose books I read, because why not? I used to write about what I was reading, and I figured I'd let you know if what I was reading was any good. I read my books in alphabetical order by author, just so you know, in case you're wondering why they seem to fall that way. I'm on the third time through my books in this way, but I keep getting more books so I keep having to start over!

Anyway, Jinn, Matthew B. J. Delaney's first novel. I didn't know until after I read this book that Delaney is a member of the New York police force, which is why the police procedural part of the book feels true (he might not have been a member when he wrote the book, but he obviously knew what he was talking about). This is a horror thriller police procedural, and I'm a bit of a sucker for those kinds of books, more than I am for straight horror.

Delaney begins the book in the South Pacific during World War II, when a bunch of Marines land on a Japanese-held island. Some of them are sent to find a missing unit, and they quickly realize that something totally evil is living on the island and killing both Americans and Japanese. The thing gets off the island, and Delaney fast-forwards to modern-day Boston, where two cops, Jefferson and Brogan, are called in to investigate a gruesome murder of a tycoon's son. They quickly learn that this isn't a normal murder, and something evil is cutting a swath through the city. Naturally, it's related to the World War II thing, and their investigations take them even further back in history.

Eventually they learn that the thing is a demon, a jinn, that needs to find the soul it once possessed back in the days of the Crusades. So of course, they have to figure out who the soul is before the demon finds it, because the soul was once the most powerful warrior of the day and being reunited with the demon would not be good. Plus, there are three other demons and three other souls, subordinate to the main one but still nasty. The four of them back in action would be even worse. So it's a race against time!!!!

Delaney does a nice job keeping the tension up throughout the book - it's 548 pages but it's a fast read. He takes time to go over the way Jefferson and Brogan investigate the crime and how they follow the clues - this is my favorite part of the book. Both Jefferson and Brogan served in Bosnia during the war, and they have a dark secret about what happened there, and Delaney does a nice job hinting around that it might or might not have something to do with the demon. Because Jefferson is the point of view character, we really only know what he does, which helps to keep things mysterious - other characters know a bit more than he does, but the reader can't know what they do. He also does a decent job making sure the book isn't too bloody - that would get boring - and that the demon's murderous rampage is focused on what it wants, which makes it a more interesting book than if it was slaughtering indiscriminately. There is a lot of violence in the book, but there's also a lot of creepiness, which is nice.

It's not a perfect book, of course. Some of the logic makes no sense, although I'm sure Delaney thinks it does. I'm not going to get into it too much because I don't want to spoil it, but for some things, you need to simply shake your head and move on (yes, this is a book about demons, but I'm talking about the internal logic within the book). The last 100 pages or so describe a confrontation in a skyscraper, and Jefferson and his ally/girlfriend, McKenna, enter the skyscraper during a charity party, yet when the violence begins, everyone has cleared out and I honestly can't remember if Delaney pointed out that the party was ending, because someone surely would have called the cops. The book ends rather abruptly, too - again, I know it's a thriller and very often those end at the climax, but I always wonder what happens in the aftermath. The survivors (I won't give away who they are) need to do some explaining, and I imagine it won't be easy to do that.

For the most part, though, Jinn is an exciting page-turner with a pretty interesting hook to it. It's a good way to wile away the hours when you're sitting in the hospital while your daughter gets a g-tube installed, in other words. It's not great literature, but it's very entertaining.

First two paragraphs:

The eight landing craft formed a jagged line of gray ship's metal across the tumbling Pacific Ocean. The small boats rose and dove through the rough waters, the ocean's shimmering green phosphorescence pounding against the ship's straight metal sides before misting over the helmeted heads of F Company. Private Eric Davis stood corralled between Marines, their helmets dripping salt water, their fatigues dark and wet. He hunched his shoulders as the landing craft caught the crest of another wave, diving through it in a nauseating roll, more water spraying onto the men.

Two months earlier he had been home in Boston. Then there was the draft. A month of training in Mississippi, his station in the Pacific, and the rest was a blur of sleepless nights aboard rolling ships, lying on canvas bunks, one on top of the other, listening to the occasional air raid warnings as Japanese Zeros buzzed above, circling like hungry vultures over their prey.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆

Pafko at the Wall by Don DeLillo. 90 pgs, Scribner, 1997.

It's been years since I read Underworld, DeLillo's massive book about the latter half of the twentieth century in the United States, and I don't feel like digging it out of storage to see how closely its first chapter hews to this novella, which was used as a template for the first chapter of the novel. I thought Underworld was overrated, but its first chapter, which describes the third playoff game between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers on 3 October 1951 is superb, and this novella is essentially the first chapter of Underworld, so it's quite good.

DeLillo's writing is characterized by a few things, among them Americana and the power of crowds, both of which are on full display in this book, telling as it does the story of a quintessentially American sport - baseball - in a crowded stadium in the quintessentially American city - New York. DeLillo gives us several characters and moves among them over the course of the famous game, which ended when Bobby Thomson hit "the shot heard 'round the world" (a ridiculously arrogant misnomer given that people across the country, much less people in other countries, may not have cared about two New York teams) - a three-run home run off Ralph Branca with one out in the bottom of the ninth inning to win the game for the Giants, who had come back from a huge deficit in the regular season just to tie the Dodgers and force a playoff (and who were summarily dismissed by the New York Yankees in the World Series that year). Thomson's home run has become part of baseball lore, not because it was the most dramatic home run in postseason baseball history (that distinction is probably shared with the two home runs that actually won World Series - Bill Mazeroski's and Joe Carter's) but because it happened in New York at a time when baseball was the absolute king of sports. DeLillo constructs a narrative out of the game that encompasses a great many American themes - individual talent in a team setting; celebrity; government secrets; fear of the Soviet Union; casual racism; and the idea of immediacy turning quickly to history. One of the reasons why this novella and the first chapter of Underworld is so much better than the rest of Underworld (from what I remember) is that DeLillo doesn't need to beat us over the head with the themes, and he tends to do that in Underworld proper (it's a long novel).

The central characters, if we can call them such, are Cotter and Bill, a teenager skipping school and a middle-aged man skipping work, who strike up a conversation while watching the ball game. Cotter was one of the boys who crashed the gate and managed to evade the police, and Bill knows this, but he doesn't care. Cotter is black and Bill is white, and again, nobody cares. Until the end of the book, when they suddenly find themselves at odds. DeLillo deftly turns this into an interesting commentary on racism in the 1950s and the way people acted without making too big a deal about it. Also at the game are Toots Shor, Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason, and J. Edgar Hoover, sharing a box. Hoover gets word during the game that the Russians tested an atomic bomb (the test was conducted over a week before the game), and that also colors the narrative, as Hoover is distracted by thoughts of death even as people around him are celebrating.

DeLillo is not a ponderous writer; his prose zips along and feels effortless and even a bit disconnected, until you take in the entire text and realize how well he's manipulated you. In this book, he doesn't force big ideas down your throat, preferring instead to allude to things that lead you to his ideas surreptitiously. He also works popular culture into his novels very well, and throughout this book we get a good sense of the times, not just the events that are occurring. And, of course, the larger narrative is about the game, and DeLillo does a wonderful job placing us at the Polo Grounds as the Dodgers and Giants battle. He's very good at this sort of thing.

DeLillo is one of my favorite writers (White Noise is one of my favorite novels, but The Names, Mao II, and Libra are also very good, as is, to a degree, Underworld), and this novella is a solid example of why. It's a bit of a curio, but if you've never read any DeLillo, it's a quick read for a primer on his style. Perhaps it will lead you to his truly great books!

First three paragraphs:

He speaks in your voice, American, and there's a shine in his eye that's halfway hopeful.

It's a school day, sure, but he's nowhere near the classroom. He wants to be here instead, standing in the shadow of this old rust-hulk of a structure, and it's hard to blame him -- this metropolis of steel and concrete and flaky paint and cropped grass and enormous Chesterfield packs aslant on the scoreboards, a couple of cigarettes jutting from each.

Longing on a large scale is what makes history. This is just a kid with a local yearning but he is part of an assembling crowd, anonymous thousands off the buses and trains, people in narrow columns tramping over the swing bridge above the river, and even if they are not a migration or a revolution, some vast shaking of the soul, they bring with them the body heat of a great city and their own small reveries and desperations, the unseen something that haunts the day -- men in fedoras and sailors on shore leave, the stray tumble of their thoughts, going to a game.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Cosmopolis by Don DeLillo. 209 pgs, Scribner, 2003.

If you're reading a Don DeLillo book for a plot, chances are you'll be disappointed. That's not to say he doesn't have interesting plots, and, in fact, Libra (which is about the Kennedy assassination) is obsessed with plots, but DeLillo also likes to muse on certain things too, and occasionally the plot kind of gets lost. Cosmopolis is an example of this, as the plot is simple enough to discern - in 2000, a young billionaire assets manager named Eric Packer decides one morning to get in his limousine and cross Manhattan Island in an effort to get a haircut. While in his car, he has many strange adventures. Meanwhile, someone is trying to kill him. Plot-wise, it's a bit thin, and DeLillo even lets us know fairly early on if the assassination plot succeeds or not, but what's fascinating about Cosmopolis is that DeLillo is such a good writer that it's just fascinating to read for the word usage and the themes he explores.

As I noted above, DeLillo is very interested in crowds and how they form history and events, and that comes into play in Cosmopolis. Eric is isolated from the outside world in his limo, but he uses CCTV cameras to watch the world from inside and often steps out of the limo to interact with people on the street. Halfway through the book, there's a bizarre anti-Wall Street protest during which the protesters direct their ire toward his limousine (DeLillo has always been very good at anticipating future events, and this book often feels eerily prescient), and the crowd intersects with Eric's isolation to create a weird, surreal atmosphere that doesn't seem to fit into anyone's reality, much less Eric's. DeLillo loves placing the person in contrast to the mob and seeing how that dichotomy plays out, and in Cosmopolis, it's more benign than in some of his other books, but it also has an element of danger.

DeLillo also explores a theme of self and what it means to be a human in the twenty-first century - Eric struggles with an existential crisis for most of the day, as he bet on the yen falling in the markets but the yen, inexplicably, continues to rise. As he watches his fortune slip away and hopes it recovers, he begins to spin off the beaten path and move into some weird territory. He's married to an heiress, but the union is only a few weeks old and Eric has a great deal of extra-marital sex during the day until he decides to steal all of his wife's money in an effort to shore up his dwindling finances. This, ironically, leads to a beautiful conversation with his wife near the end of the book. He also begins to act erratically, which of course puts him in more and more danger from his unknown assassin.

I'm not sure how much DeLillo is known for his sense of humor, but his detached style of dialogue lends itself well to absurd humor, and this book is chock full of odd, seemingly off-tangent conversations that illuminate the characters, all of which are very well created even if they only appear on a few pages. DeLillo's prose is brisk and concise, the book is short, and we get a very good sense of the disconnect many Americans feel (even though Eric is a billionaire, he's still an American) from society in this turbulent era. DeLillo never seems to set out to tap into the zeitgeist, but he always seems to do so almost effortlessly.

This is another quick DeLillo book that will give you a good sense of his writing before you tackle something like Underworld or Libra, which are far longer. Give it a look!

First five paragraphs:

Sleep failed him more often now, not once or twice a week but four times, five. What did he do when this happened? He did not take long walks into the scrolling dawn. There was no friend he loved enough to harrow with a call. What was there to say? It was a matter of silences, not words.

He tried to read his way into sleep but only grew more wakeful. He read science and poetry. He liked spare poems sited minutely in white space, ranks of alphabetic strokes burnt into paper. Poems made him conscious of his breathing. A poem bared the moment to things he was not normally prepared to notice. This was the nuance of every poem, at least for him, at night, these long weeks, one breath after another, in the rotating room at the top of the triplex.

He tried to sleep standing up one night, in his meditation cell, but wasn't nearly adept enough, monk enough to manage this. He bypassed sleep and rounded into counterpoise, a moonless calm in which every force is balanced by another. This was the briefest of easings, a small pause in the stir of restless identities.

There was no answer to the question. He tried sedatives and hypnotics but they made him dependent, sending him inward in tight spirals. Every act he performed was self-haunted and synthetic. The palest thought carried an anxious shadow. What did he do? He did not consult an analyst in a tall leather chair. Freud is finished, Einstein's next. He was reading the Special Theory tonight, in English and German, but put the book aside, finally, and lay completely still, trying to summon the will to speak the single word that would turn off the lights. Nothing existed around him. There was only the noise in his head, the mind in time.

When he died he would not end. The world would end.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

That's it for this month. I'm planning to do more in-depth reviews of the recent graphic novels I have bought, so keep looking out for those. And I'll be back in a month (I'd like to post these on the last day of the month, but this time around I was coming home from vacation, and the final day of February is a Wednesday, so we'll see) with more of these mini-reviews (and probably not as many books, as two of them this month were awfully short). I hope you enjoy them!