The countdown concludes with the last three writers that you voted as your favorites of all-time (out of roughly 1,023 ballots cast, with 10 points for first place votes, 9 points for second place votes, etc.).

3. Neil Gaiman – 2862 points (56 first place votes)

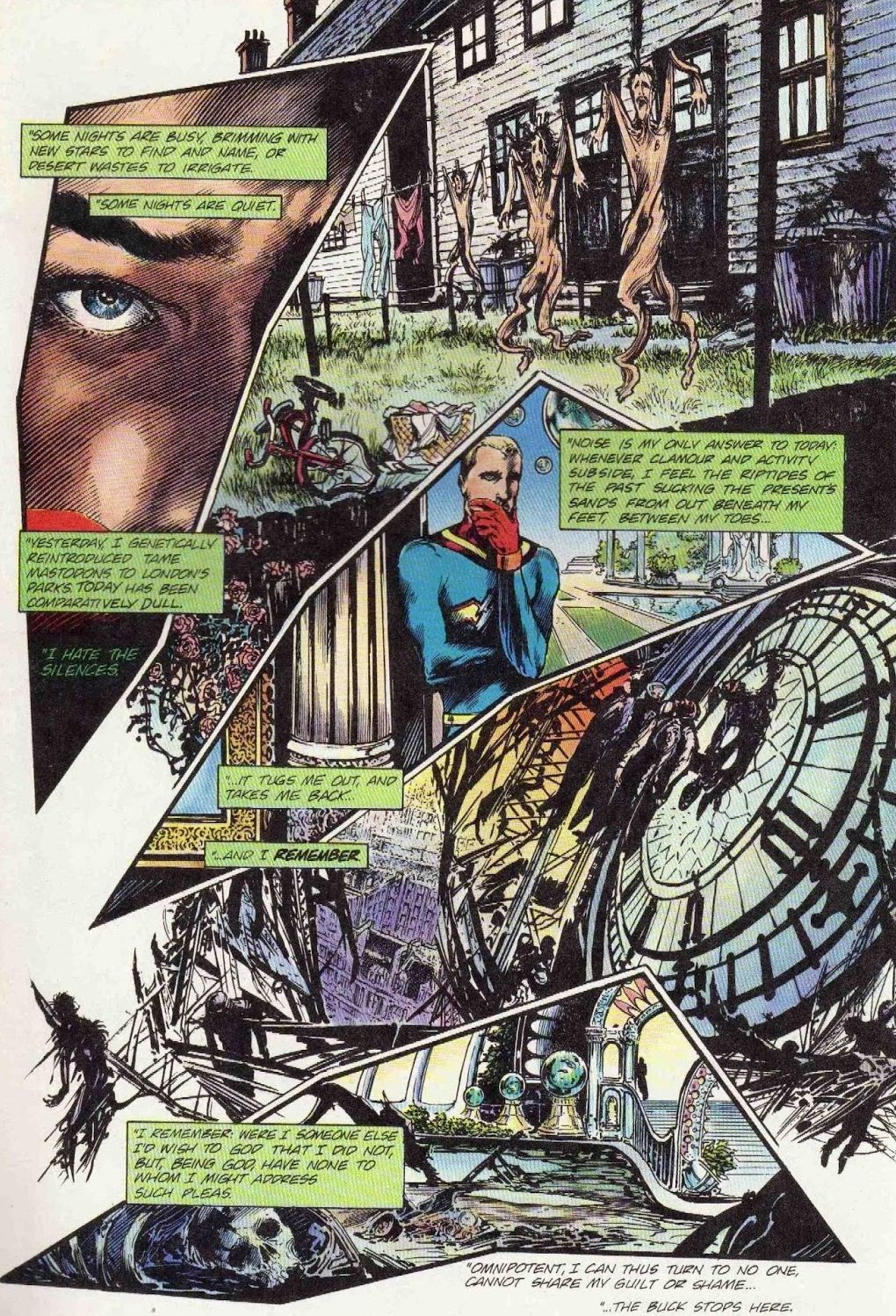

Neil Gaiman wrote one of the most acclaimed ongoing series of the 1990s, the brilliant Sandman, about Morpheus, the embodiment of dreams. The framework of the series allowed to give Gaiman the freedom to tell all sorts of different stories and he adapted to this beautifully, giving us an epic tale broken up into smaller stories.

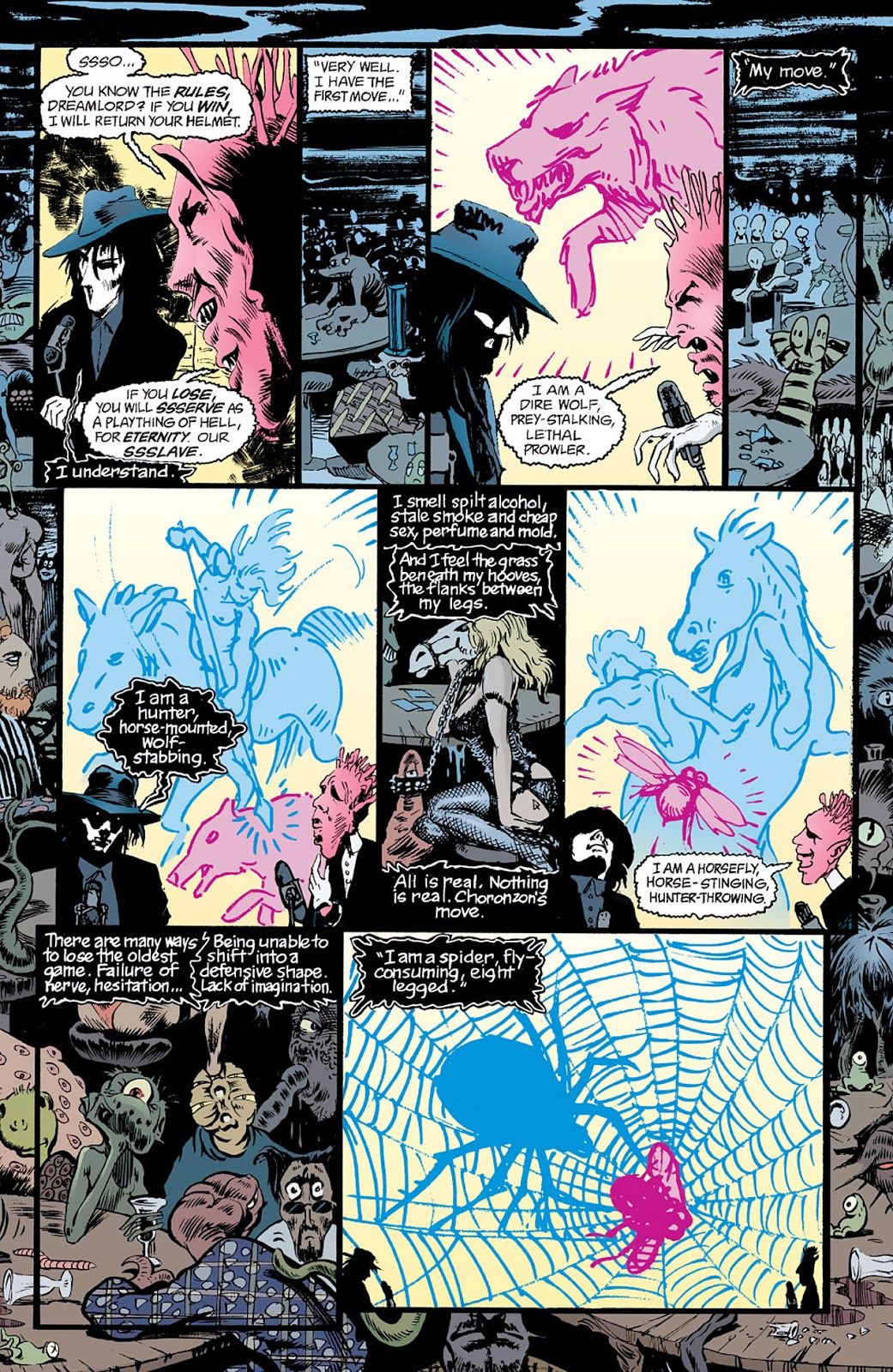

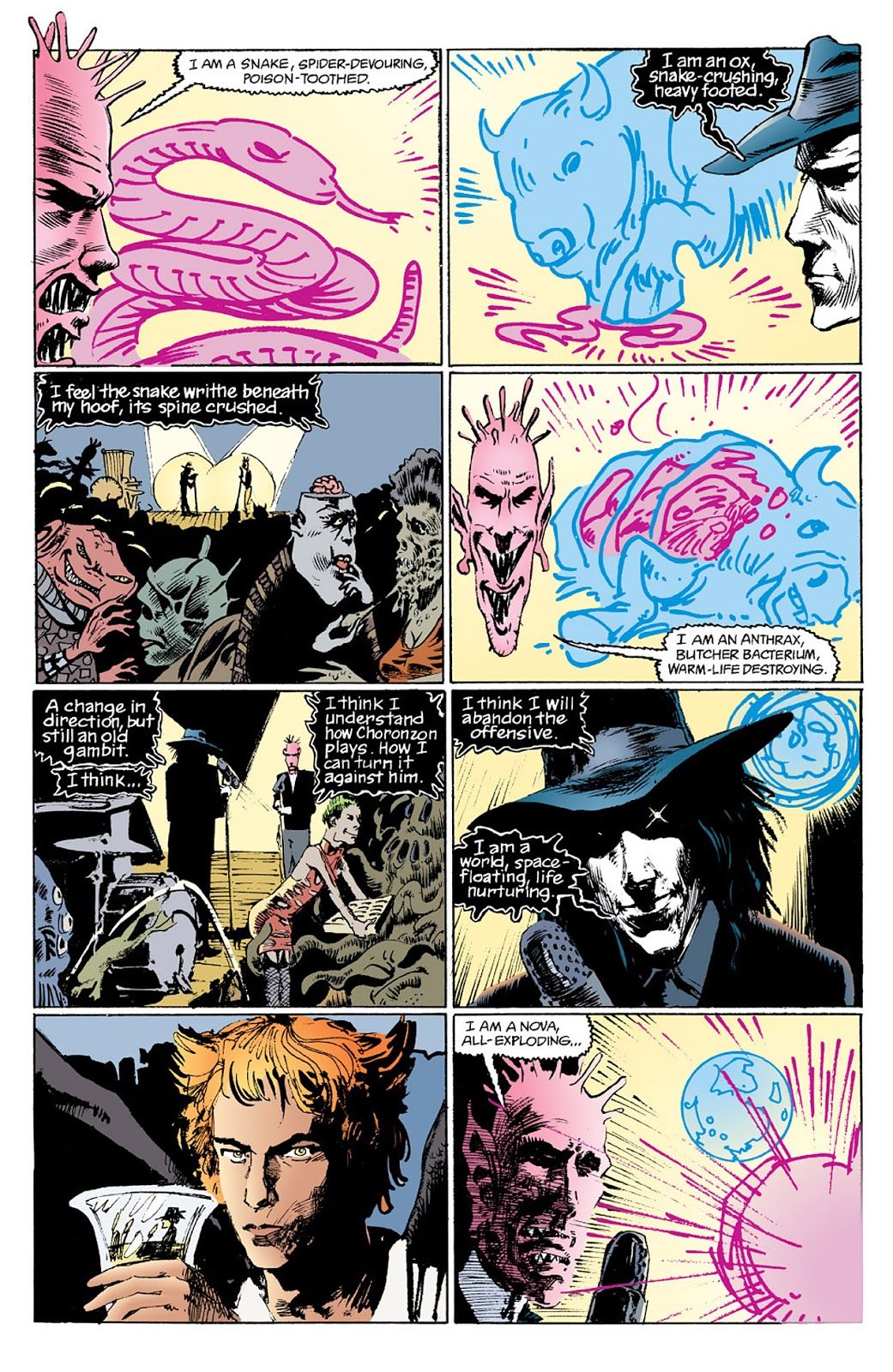

Very early on, Gaiman showed off his impressive way with words in a sequence where Morpheus must battle a demon in a battle of wits to secure one of Morpheus' items of powers that had been lost years earlier...

Wow, right?

Hell was the setting for one of the greatest stories in Sandman's history, Season of Mists, where Lucifer gains his revenge on Morpheus by GIVING him hell...literally. What follows is an entertaining exploration of what the universe would be like without Hell, along with a brilliant piece of mythology work as Gaiman shows all the various other deities (like the Norse Gods and the Egyptian Gods, etc.) showing up to bargain with Dream for the rights to such prime inter-dimensional real estate.

To show what I mean about how varied the stories Gaiman could tell with Gaiman, he used the temporary absence of hell to tell some stories about the souls who now have nowhere to go, which led to the charming Dead Boy Detectives (two boarding school boys, one a ghost and the other tormented by OTHER ghosts until he, himself, passes) who decide to become ghost detectives.

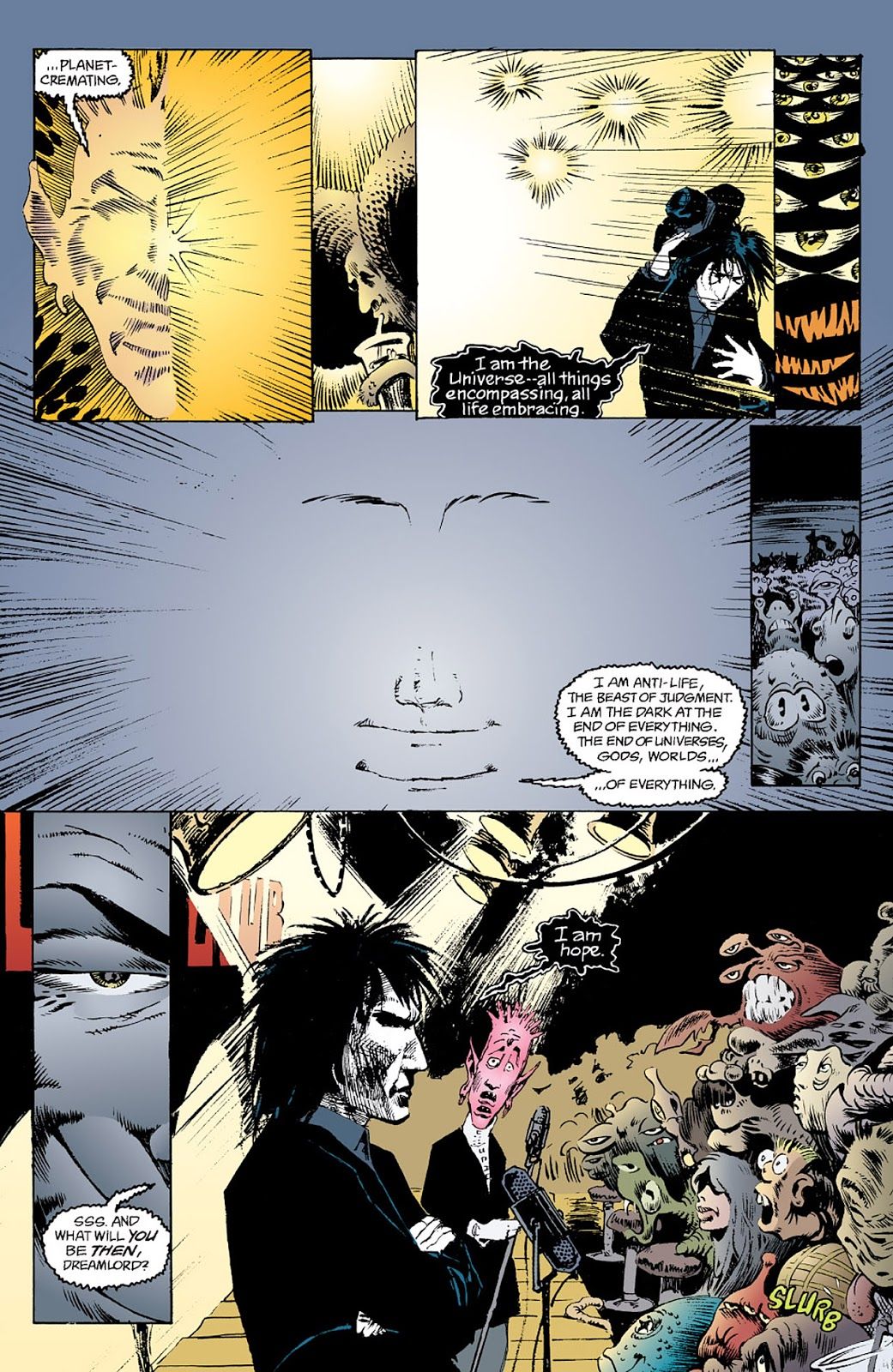

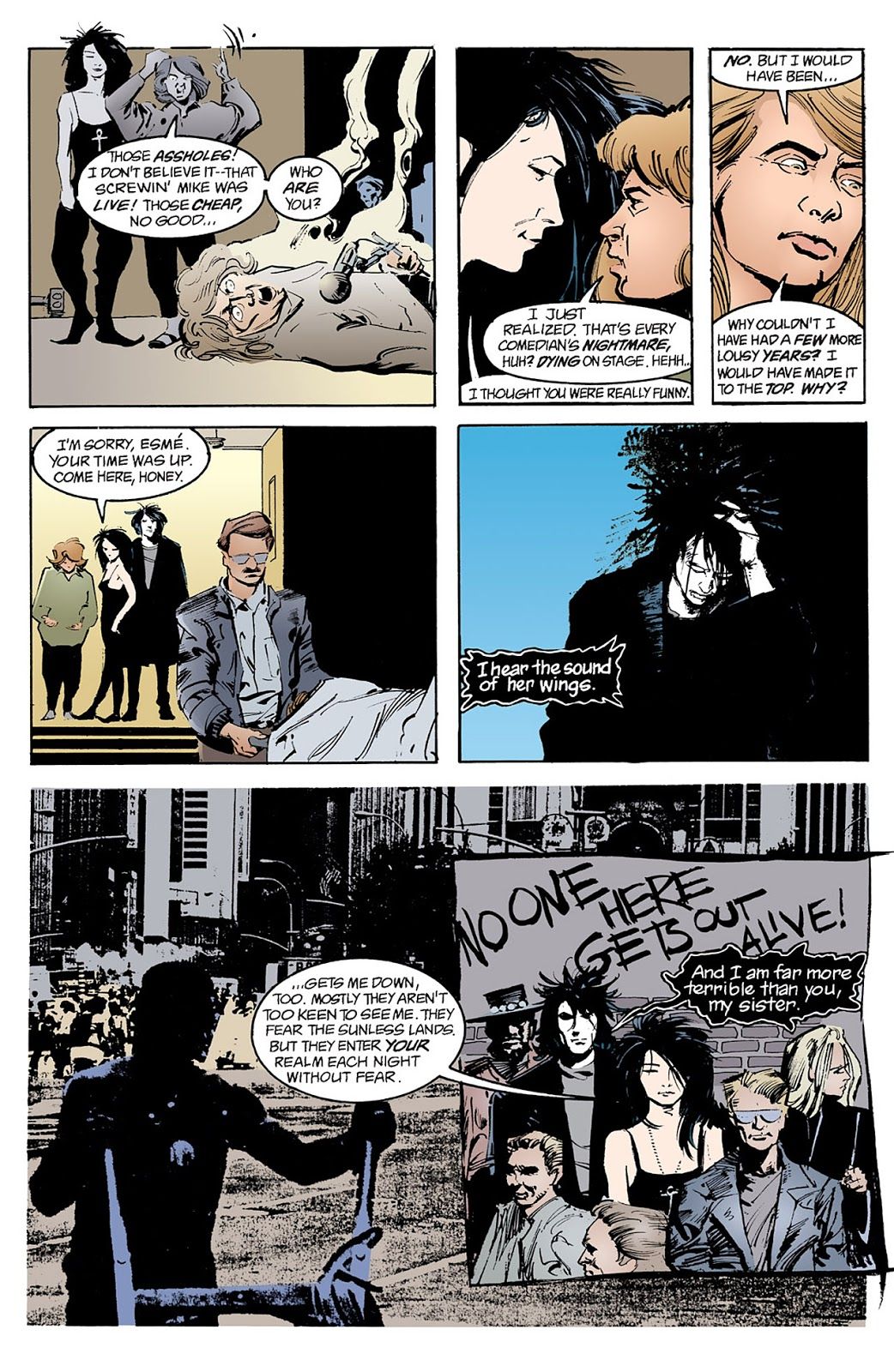

Speaking of Death, possibly the greatest creation of Gaiman's was Morpheus' sister, Death herself...

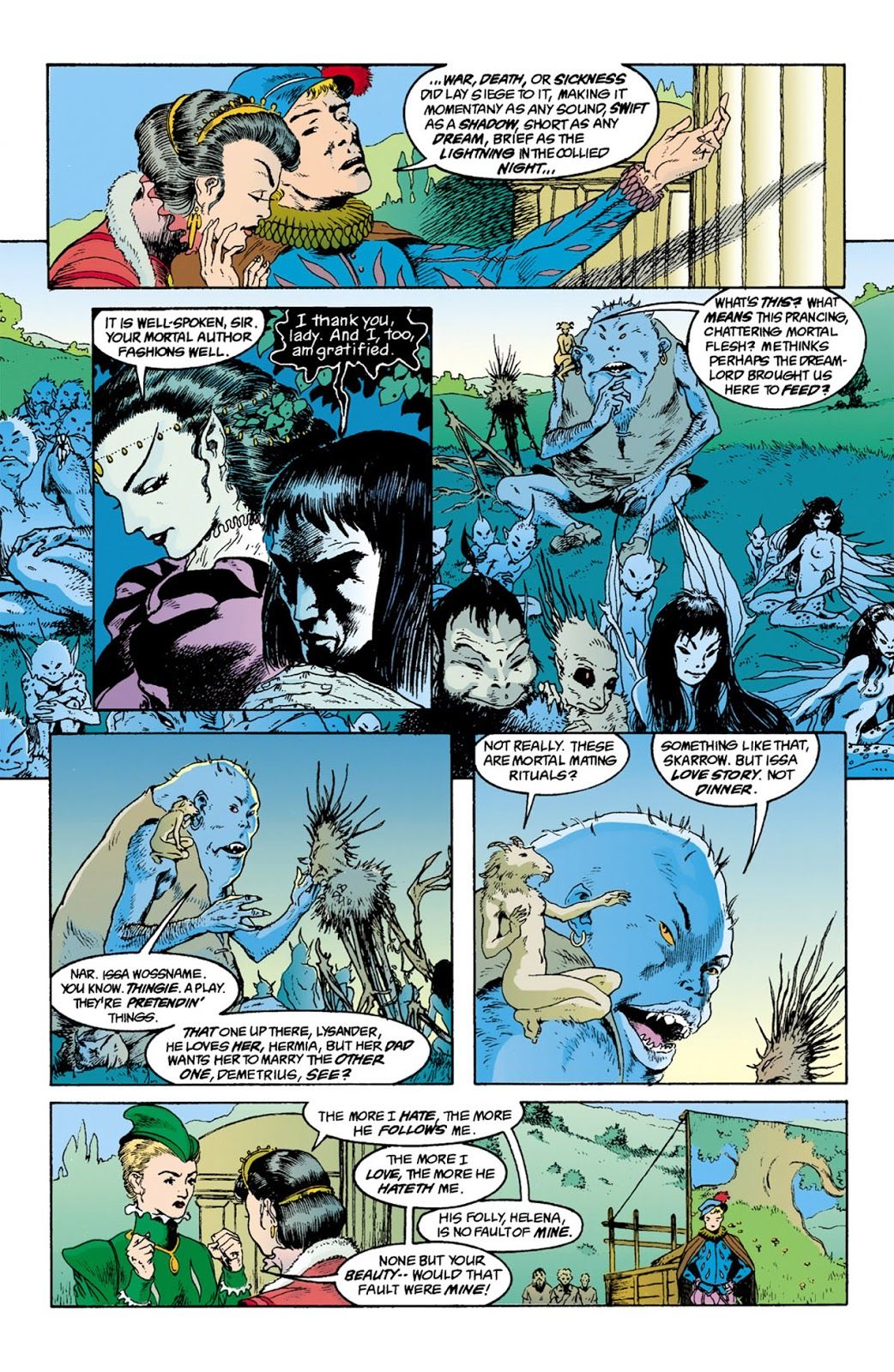

In one of the most famous issues, Shakespeare and his actors put on Midsummer's Night Dream for actual faeries...

Gaiman WAS doing other work other than Sandman at the time, though, of course. Right around the time he was doing Sandman, he rebooted Black Orchid, which was Dave McKean's first American comic book work. Gaiman did a memorable origin story for Riddler in a Secret Origins Special. Also right around the time he was doing Sandman, he also took over on Miracleman from Alan Moore. Gaiman wrote an excellent graphic novel with McKean art called The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch. Also, of course, he wrote two excellent miniseries featuring Death and he did some other Vertigo tie-ins.

Since Sandman ended, Gaiman has mostly worked (very successfully) in prose (and helping to adapt some of his works to film and TV), but he has done a number of comic book stories, as well, including some projects for Marvel, a Batman two-parter and occasional returns to his Sandman characters for DC. He will be finally finishing his Miracleman run for Marvel with Mark Buckingham, who worked on the series with Gaiman in the early 1990s.

2. Grant Morrison – 3247 points (91 first place votes)

When Grant Morrison started on Animal Man, the character was such a minor hero that even Morrison's intriguing take on the character was only approved for a four-issue miniseries. However, once the series came out, the response was so positive that it was quickly turned into an ongoing series, which Morrison would work on for 26 issues, with artwork by Chas Truog and Tom Grummett (in some of his earliest comic book work!).

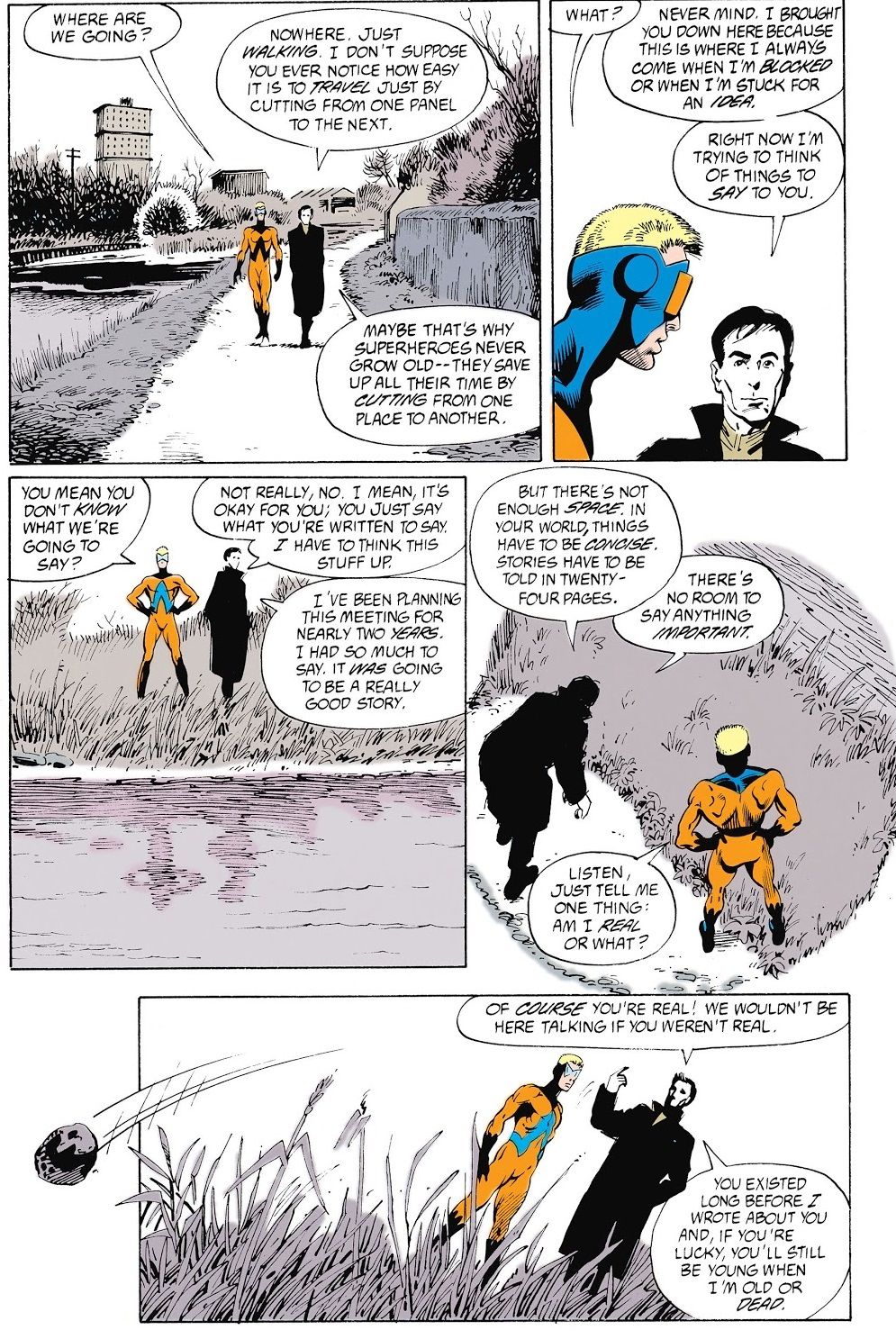

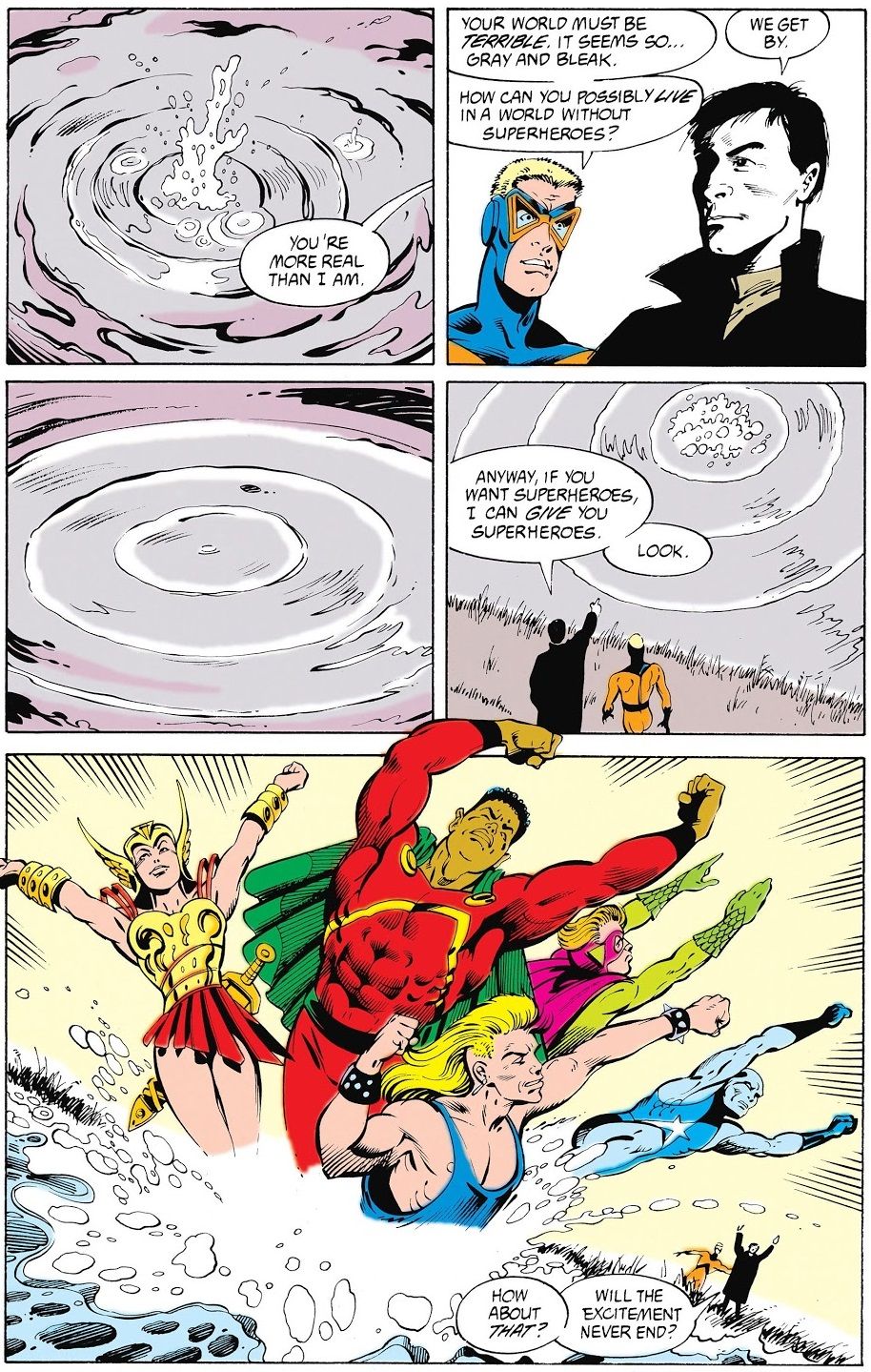

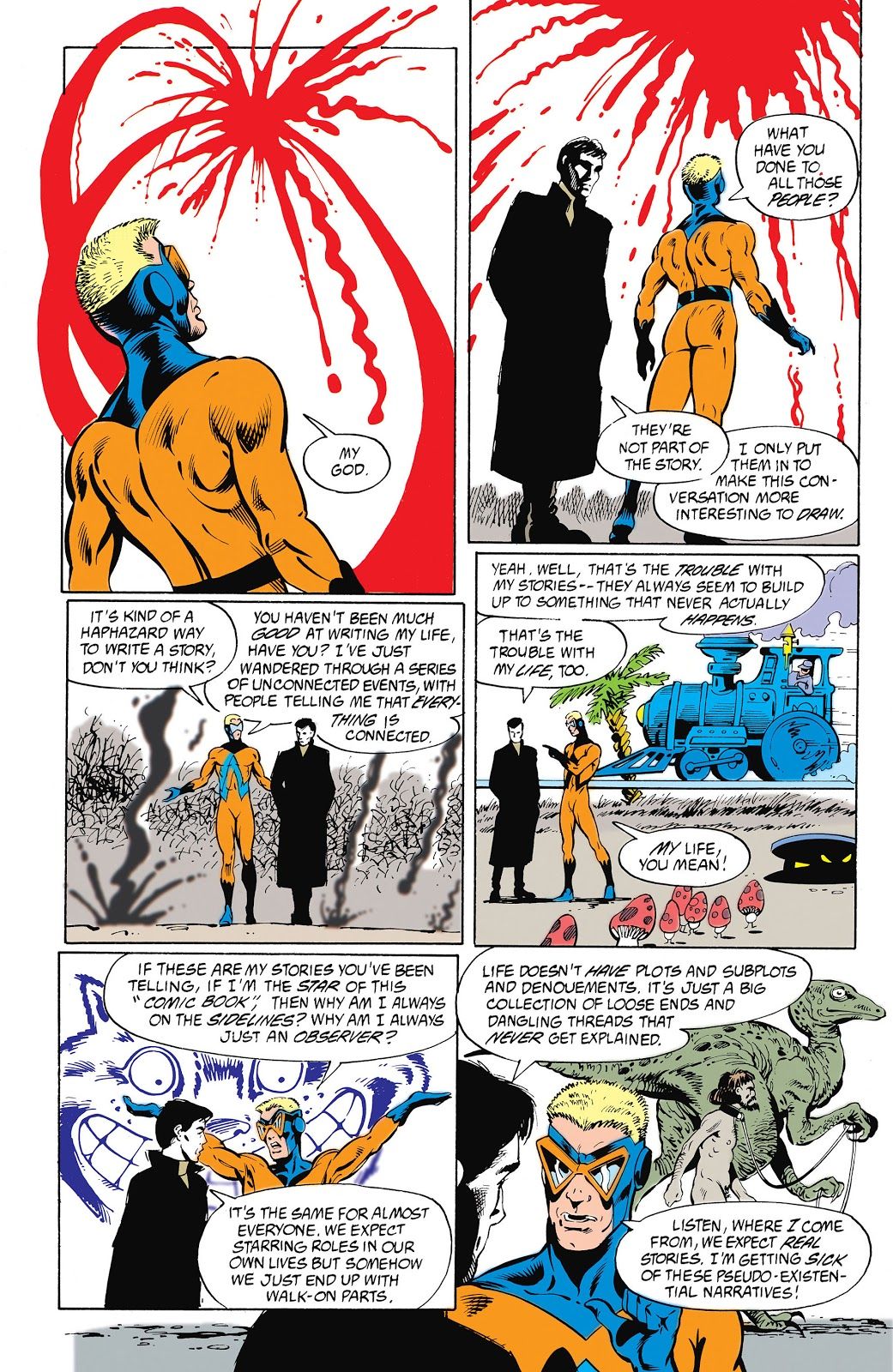

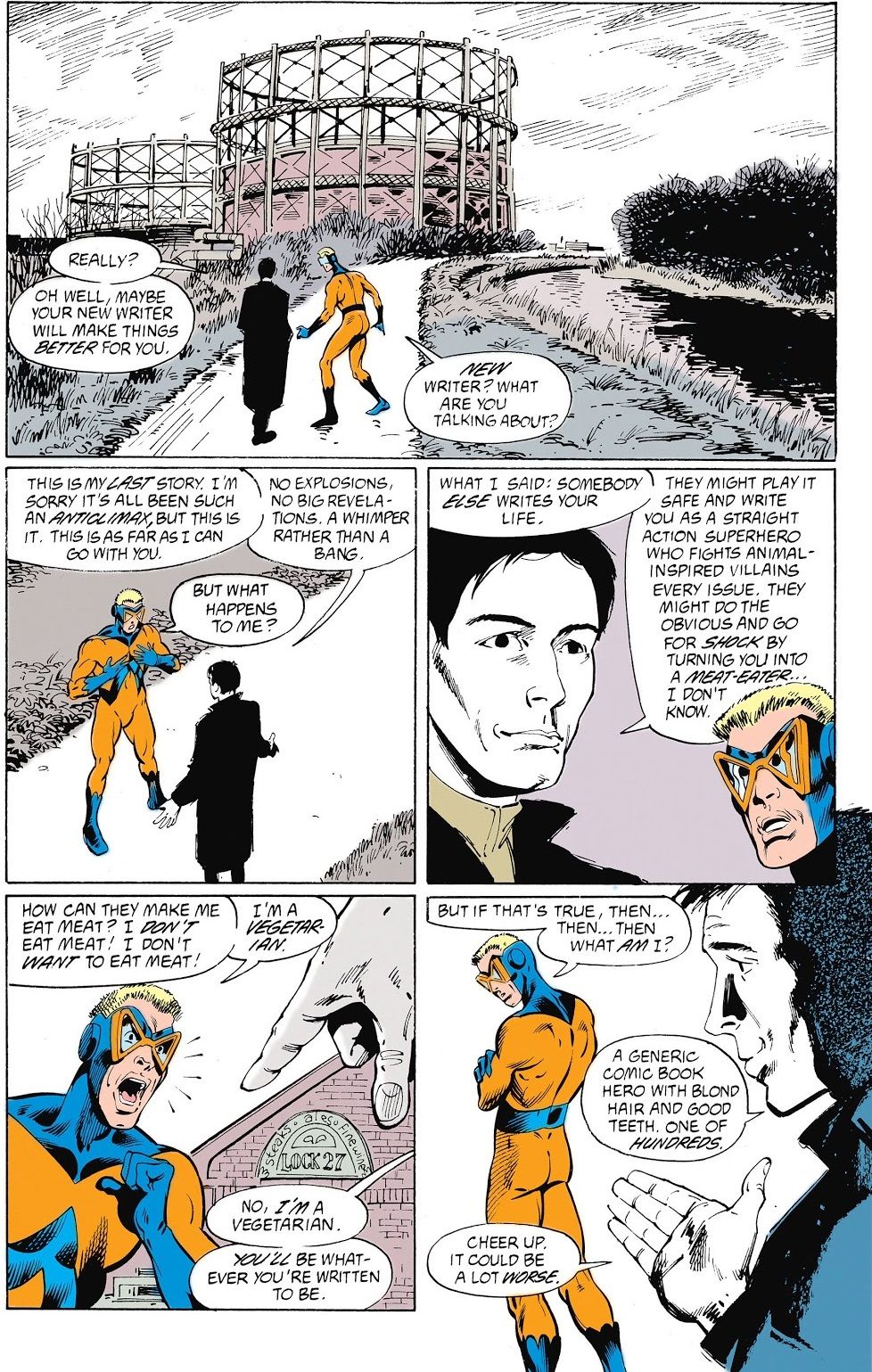

The two most remembered aspects of Morrison's run were their work with environmentalism (which Animal Man, who gains his powers by a connection to animals, was obviously a big proponent of) and metafiction.

The former led to the classic issue where Animal Man is about to kill a guy who was mass-murdering animals, until a dolphin saves him, explaining that dolphins don't believe in revenge. During these early issues, Morrison also had Animal Man encounter a number of other animal-themed heroes, such as Vixen, B'wana Beast and Dolphin.

The latter led to the concluding arc, which involved characters in limbo, the acknowledgment that DC's Crisis had actually happened and that there used to be a different continuity, and even an introduction between Animal Man and Morrison, who discussed the problems Morrison had given Animal Man during the series.

Probably the backbone of the series, though, was Animal Man's status as an "Everyman" figure. Buddy Baker had a wife and two children, and he was a lot more normal than other superheroes (which is presumably why Morrison tried to downplay Animal Man becoming a member of Justice League Europe).

Animal Man paired with their run on Doom Patrol made Morrison one of the most acclaimed writers in comics, and they took that acclaim and turned it into commercial success, as well, with their revamp of the Justice League.

With JLA, Morrison basically invented the widescreen action comic (which Authority probably perfected, but with much less famous characters), as each Morrison arc was a BIG...DRAMATIC...ACTION EPIC!!! It was their ode to the Silver Age, where the Justice League would go on bizarre adventures all the time, only with modern comics, Morrison (and artist Howard Porter) were able to do everything BIGGER than they did back in the 60s, and it resonated with fans, making JLA the most popular superhero comic at DC, taking a franchise that was in the pits and making it relevant again.

Perhaps most importantly, Morrison had a story where they used the Blue Superman and did something COOL with him, which is probably the most impressive part of Morrison's whole run.

Dude WRESTLED AN ANGEL!

This really was not some deep comic book, it was pure entertainment, but it was well-written, well-executed entertainment that created a practical cottage industry of tie-ins for DC.

Morrison then went to Marvel and then successfully revamped the X-Men, as well!

Marvel was in bankruptcy when they hired Grant Morrison to become the main X-Men writer, and they basically gave them total freedom to do what they wanted, and what they wanted to do was to make some major changes in the title, from eliminating the traditional costumes (going with a "leather jackets" look), which is similar to what the movies did, to making Beast look like the Beast from the famous Jean Cocteau film from the 1940s, adding Emma Frost to the X-Men having it be revealed that home sapiens were on the verge of extinction and, of course, introducing a new bad guy named Cassandra Nova who systematically leads to the Sentinels destroying the mutant population of Genosha. And that was just the first story arc!!!

After there, Morrison kept the pace quick and the new characters a-plenty, from Xorn, Angel, Beak and the Stepford Cuckoos to John Sublime, Fantomex and Kid Omega.

The book was set-up as a sort of homage to Chris Claremont and John Byrne's run, in that Morrison would attempt to address the same stories they did, just in a different manner. They had a Sentinel story? Morrison would do a Sentinel story. They had a Shi'ar story? Morrison would do a Shi'ar story. And so on and so forth.

Morrison's final story arc (set in the present) was a big Magneto story where Morrison mocked the very nature of comic cycles of death and resurrection. They also killed off a few characters, and had Emma Frost and Scott Summers end up together.

Morrison returned to DC Comics for the brilliant We3 (about a group of animals turned into killers and then released into the wild by their trainer) and All Star Superman.

All Star Superman was both a reimagination of Superman as well as a bit of a farewell to the character. The story is basically about the death of Superman, as his death is foretold in the first issue and the comic depicts the last year in the life of Superman.

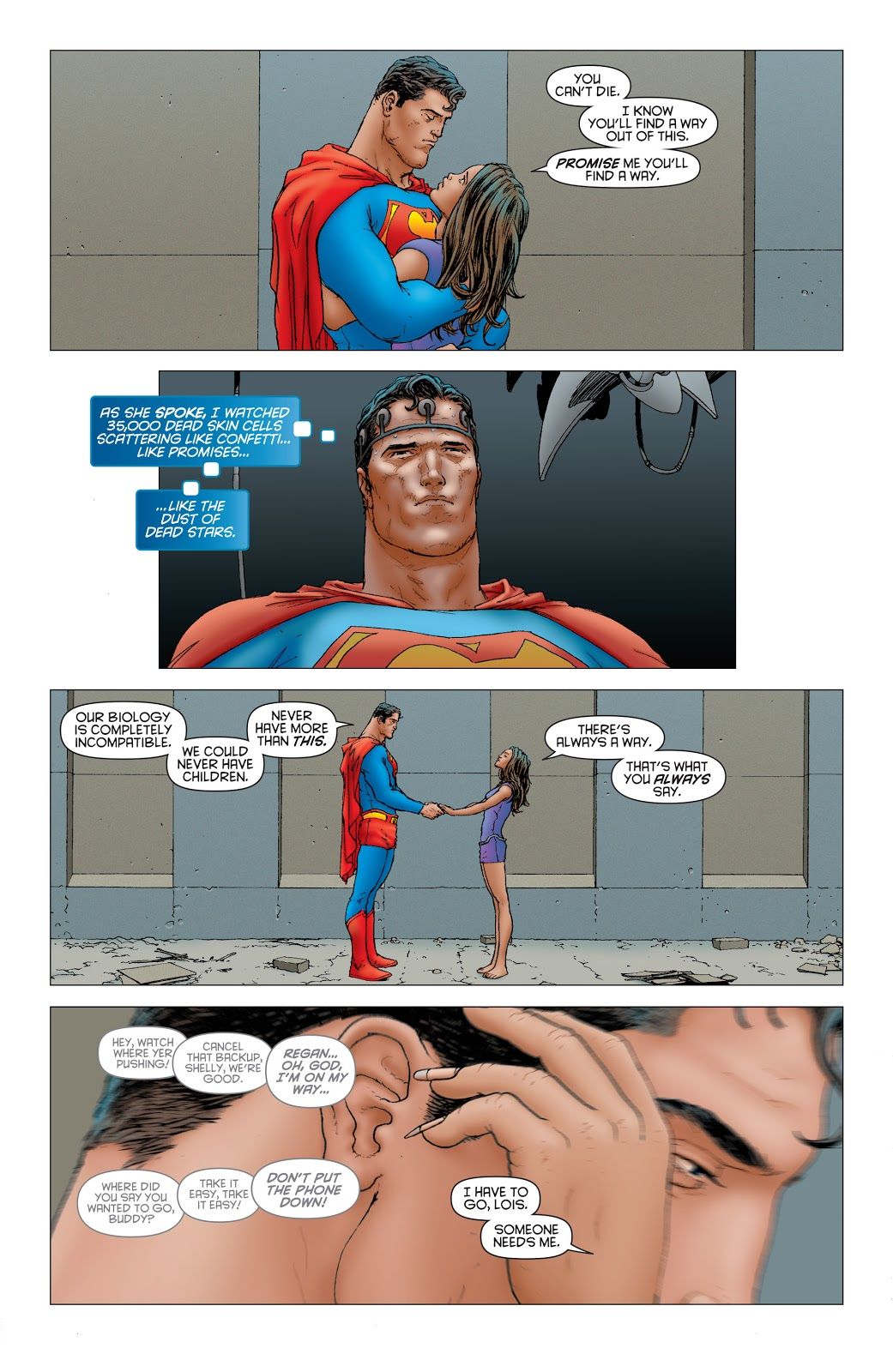

During that year, Superman has to complete twelve trials before he dies. As he completes the trials, Morrison and Quitely deliver brilliant new approaches to classic Superman plots.

Possibly one of the coolest aspects of All Star Superman is that it is not, in the least bit, cynical. It's quite a feat to see a re-envisioning of Superman that does NOT involve some sort of post-ironic cynical approach to the character.

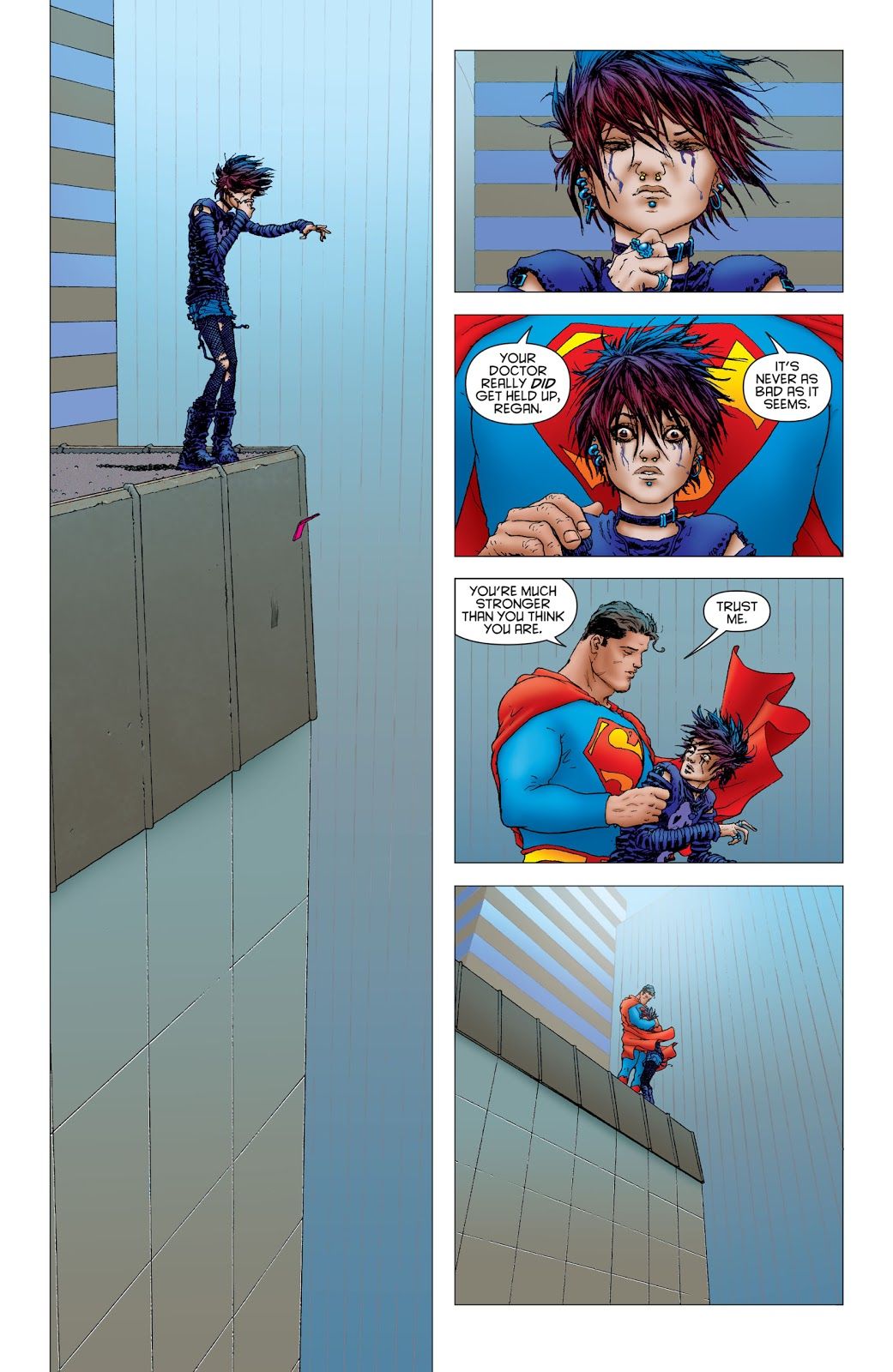

Nothing likely embodies that more than this scene in All Star Superman #10, where Superman is dying but takes the time to help a young girl...

Awwwwwwwwwww.

In addition, the story was told with a series of (mostly) one-off issues, so each issue was like its own little epic, they just combine to tell one long story of Superman's last year of life.

Morrison's take on Superman and his supporting cast was innovative while completely familiar.

Morrison then did an almost decade-long run on Batman, where they did some really cool stuff with the character...

They did a major crossover, Final Crisis, which led to an acclaimed mini-crossover event called Multiversity. They also had a strong run on Green Lantern and a return to Superman in Superman and the Authority (sort of bringing their DC stories to a close, although I'm sure there will always be the possibility for more stories in the future). They also did some strong work for BOOM!, as well. They're currently having success as a prose novelist.

1. Alan Moore – 4868 points (185 first place votes)

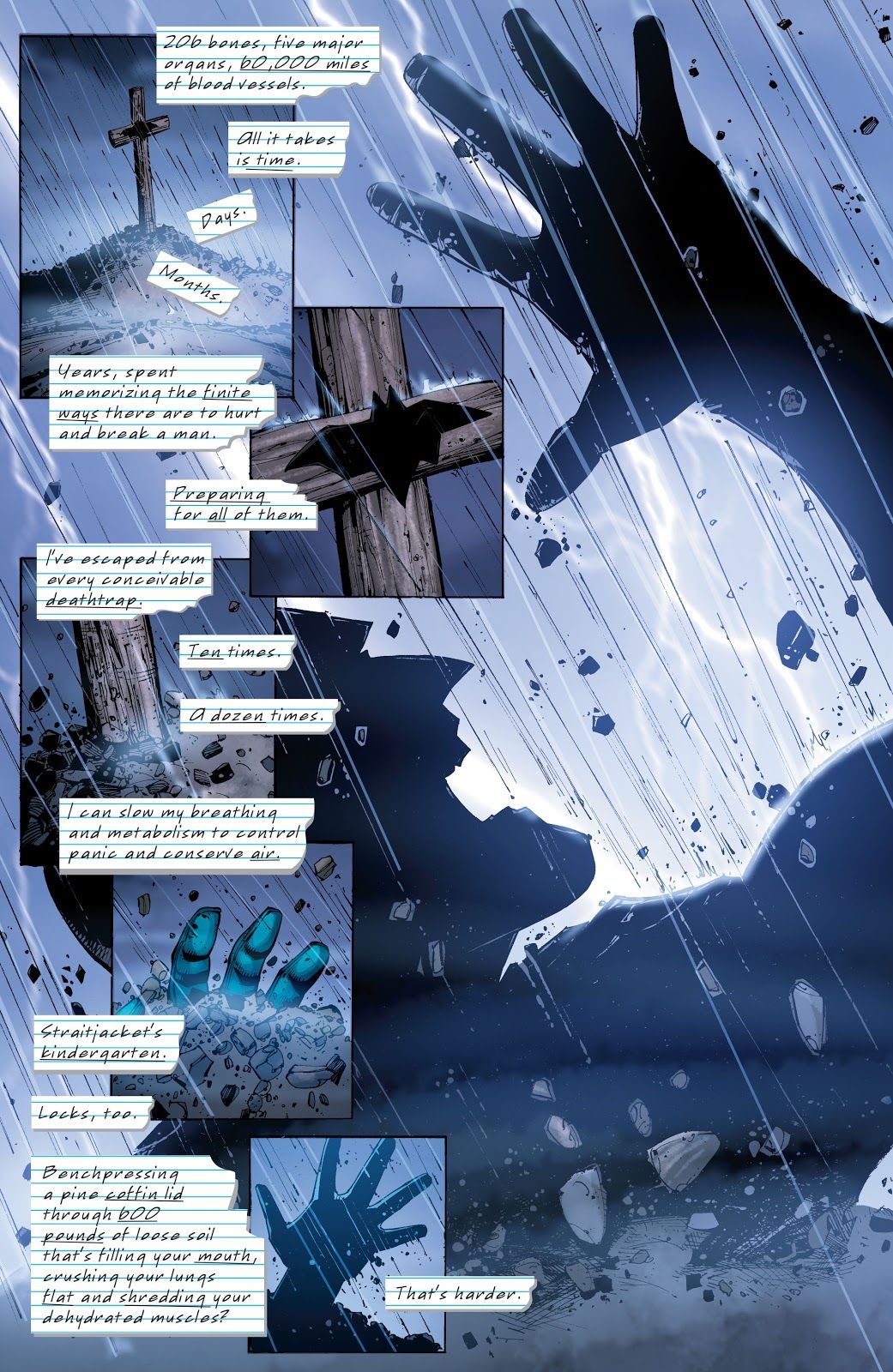

Alan Moore's big break was on a revival of the classic British superhero, Marvelman (who was, himself, basically a riff on Captain Marvel). He and Garry Leach brought Marvelman back, only with a postmodern edge. Reporter Michael Moran keeps having crazy dreams about superpowers, until he says the magic word, "Kimota!" and is transformed into Marvelman!

It is soon revealed that the Marvelman stories of the past were part of a government experiment with fusing alien technology with humans, to create superhumans, and the government filled the heads of Marvelman, Young Marvelman, Marvelwoman and Kid Marvelman with memories of superpowered adventures, and then tried to kill them when their experiments were over. The nuke meant to kill them all only killed Young Marvelman. Marvelman just became Michael Moran, and forgot about it all, until his memory returned.

Kid Marvelman, meanwhile, had gone mad with power, and was now a sociopathic killer. Marvelman fights him, and gets him to say HIS magic word, turning back to a young boy named Johnny Bates. Bates is placed into a group home.

The rest of the Warrior run detailed the history of how Miracleman (changed name after legal threats from Marvel) formed, as well as learning that Moran's girlfriend, Liz, was pregnant. Soon we had the most famous Miracleman storyline, where young Johnny Bates is sexually assaulted during his stay in the group home, forcing him to turn into Kid Marvelman again, who has now just totally snapped, leading to an amazingly graphic single-handed destruction of London - it's waaaaaaaaaay beyond the pale.

Miracleman (with help of some other heroes) finds a way to force Kid Miracleman to turn back into Johnny, and Miracleman has to make a dreadful choice...

Chilling.

Moore left the book to Neil Gaiman after this storyline, with Moore's last issue being #16.

By this point, Moore had already begun Swamp Thing, his entry into American comics.

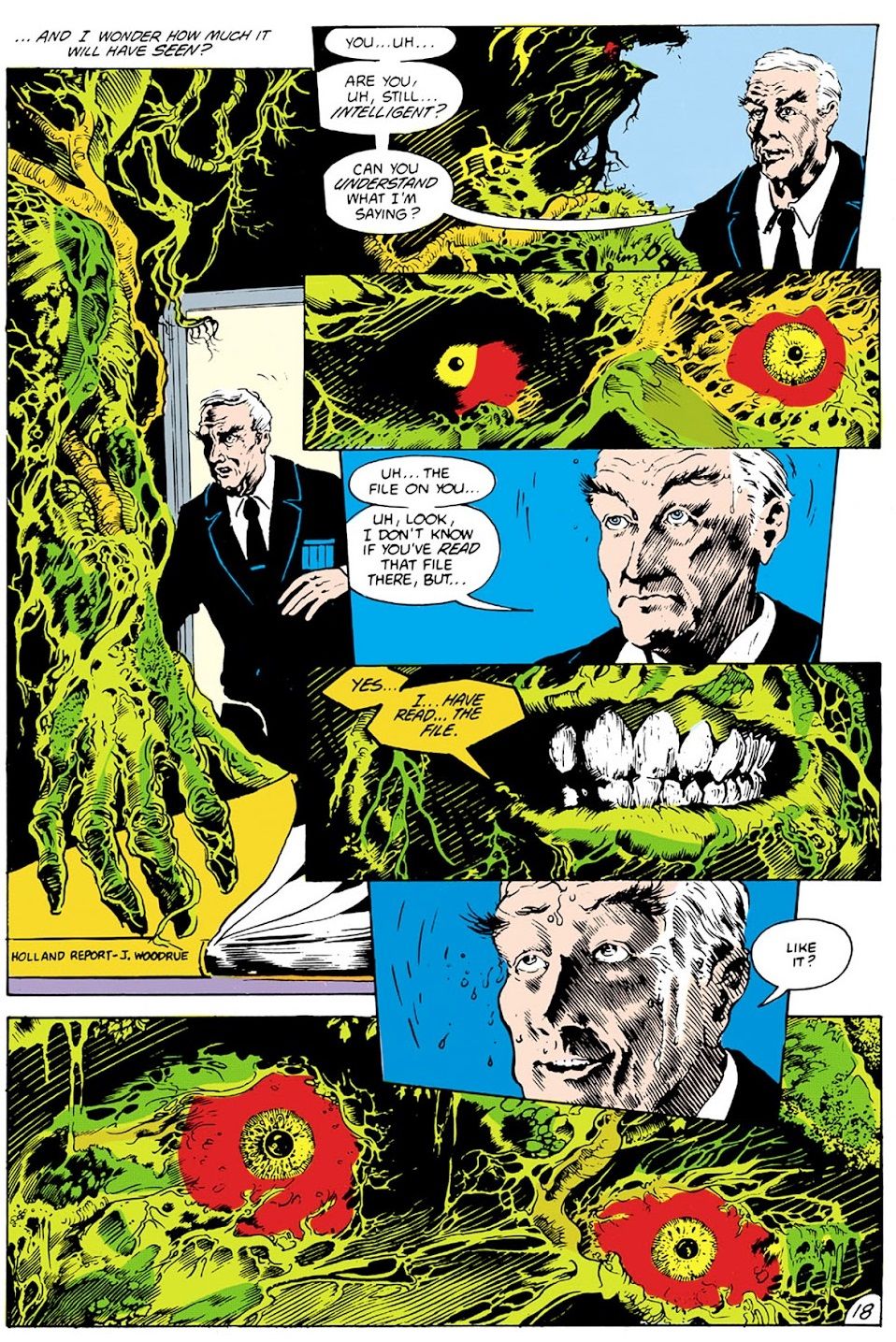

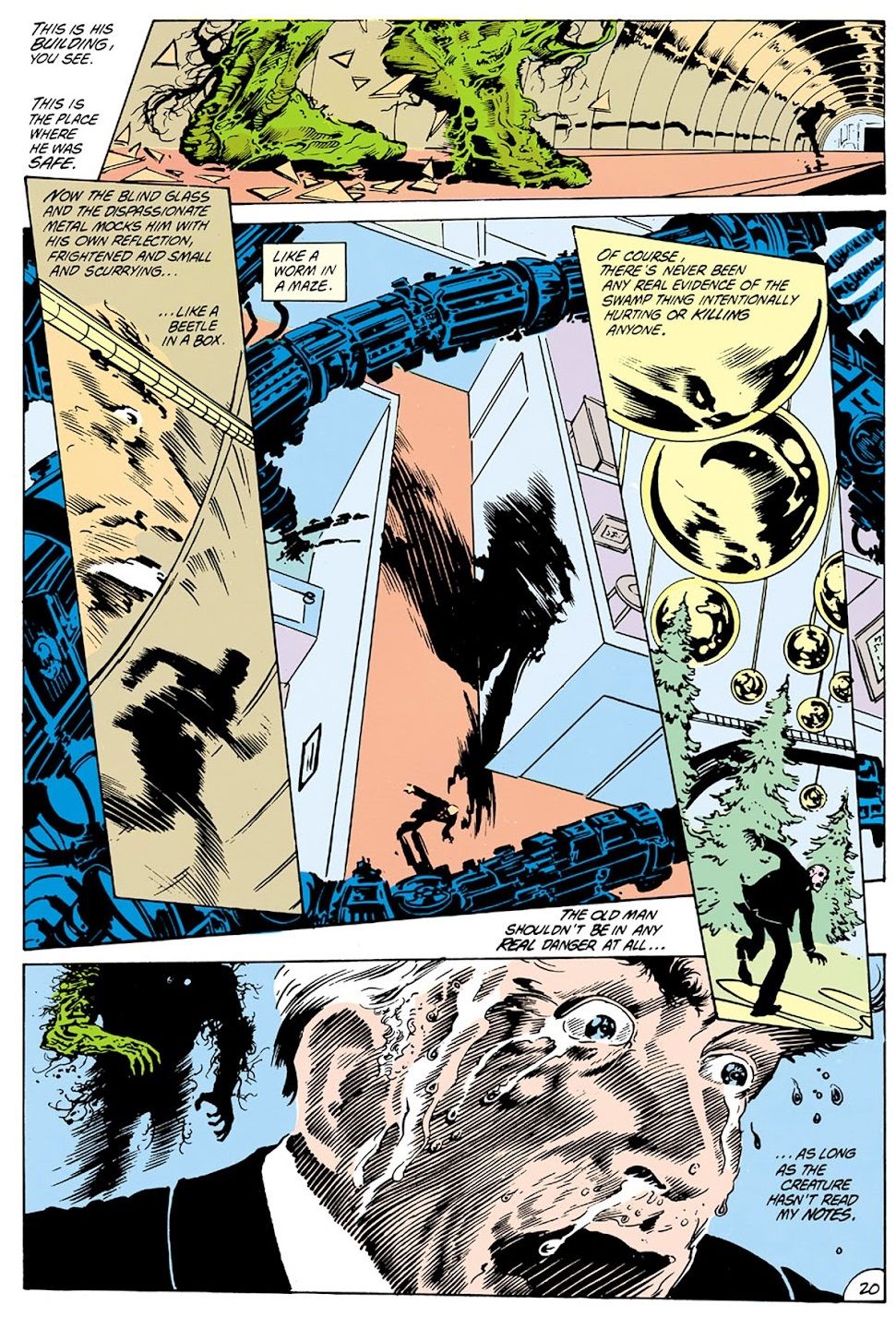

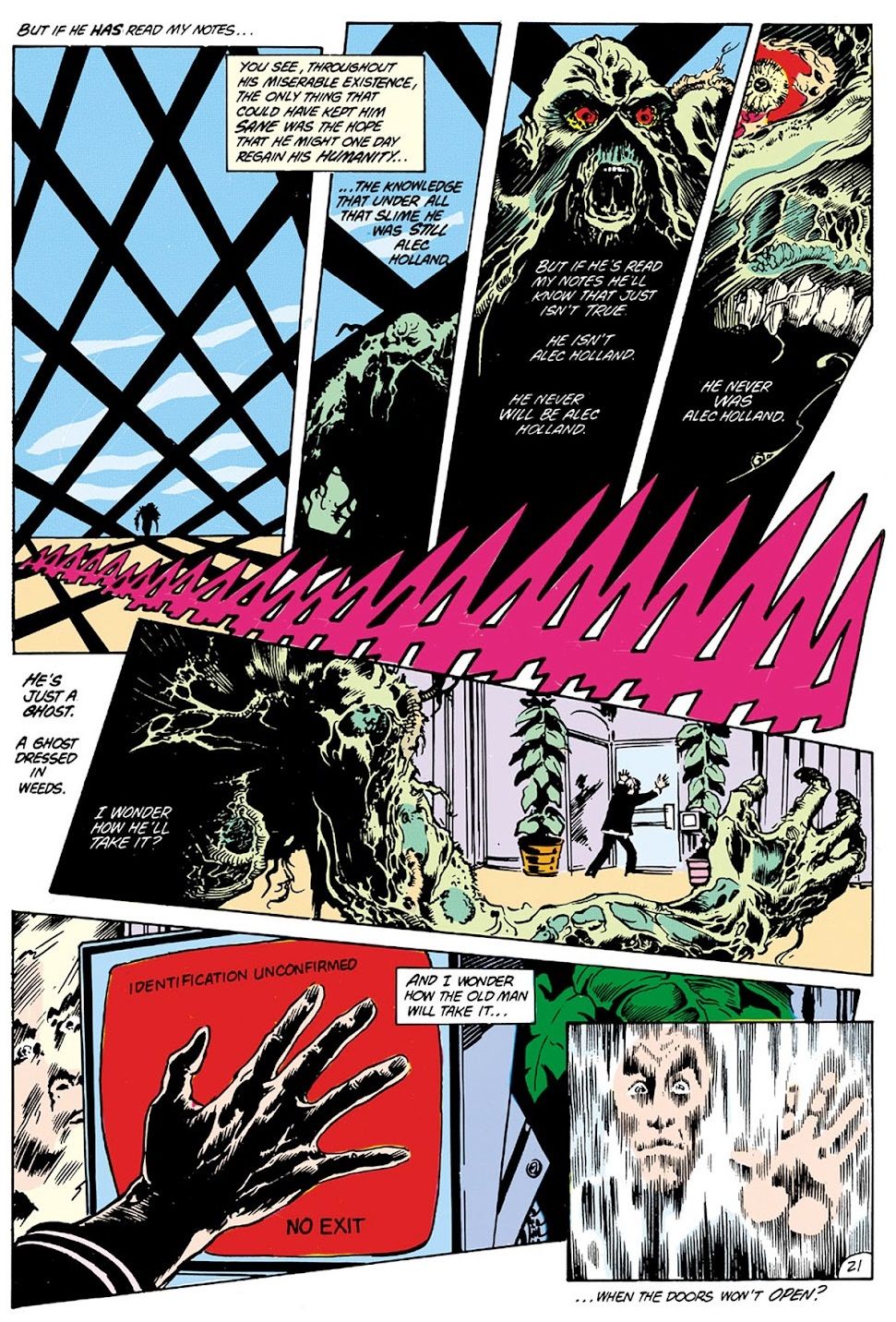

After wrapping up the storylines of the previous writer, in his second issue on the series, Moore dropped the big one - "Anatomy Lesson." There have been a number of other significant retcons with titles before, but they all paled in comparison to what Alan Moore did with "Anatomy Lesson," which revealed that the entire origin of Swamp Thing was false - Alec Holland was not transformed into Swamp Thing during a chemical explosion - instead, the chemicals animated a group of vegetation into THINKING it was Alec Holland.

Later, Moore would also explain the various inconsistencies of Swamp Thing's origin by saying that there were many different Swamp Things who all had the same basic origin. Clever meta-fiction work by Moore.

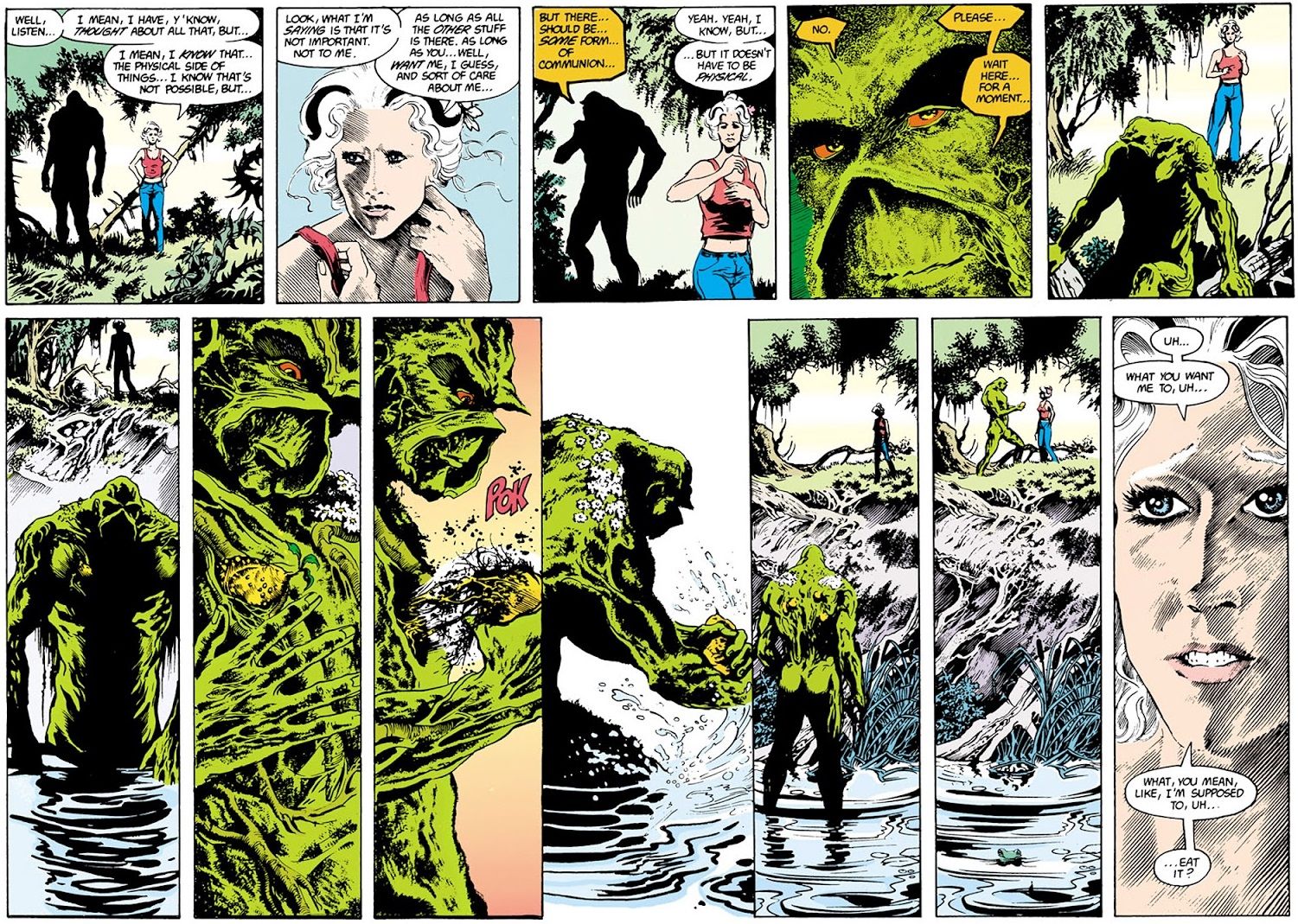

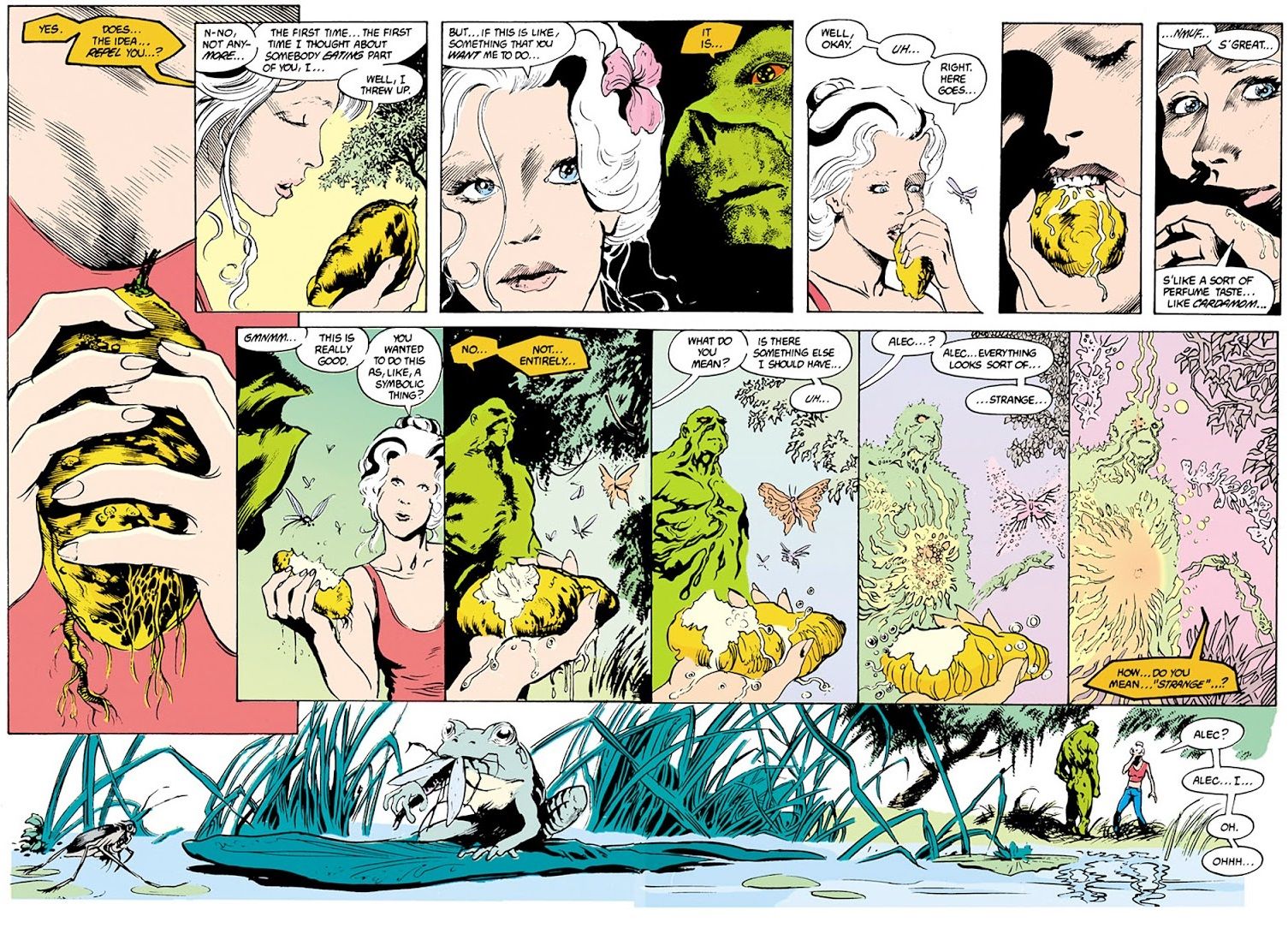

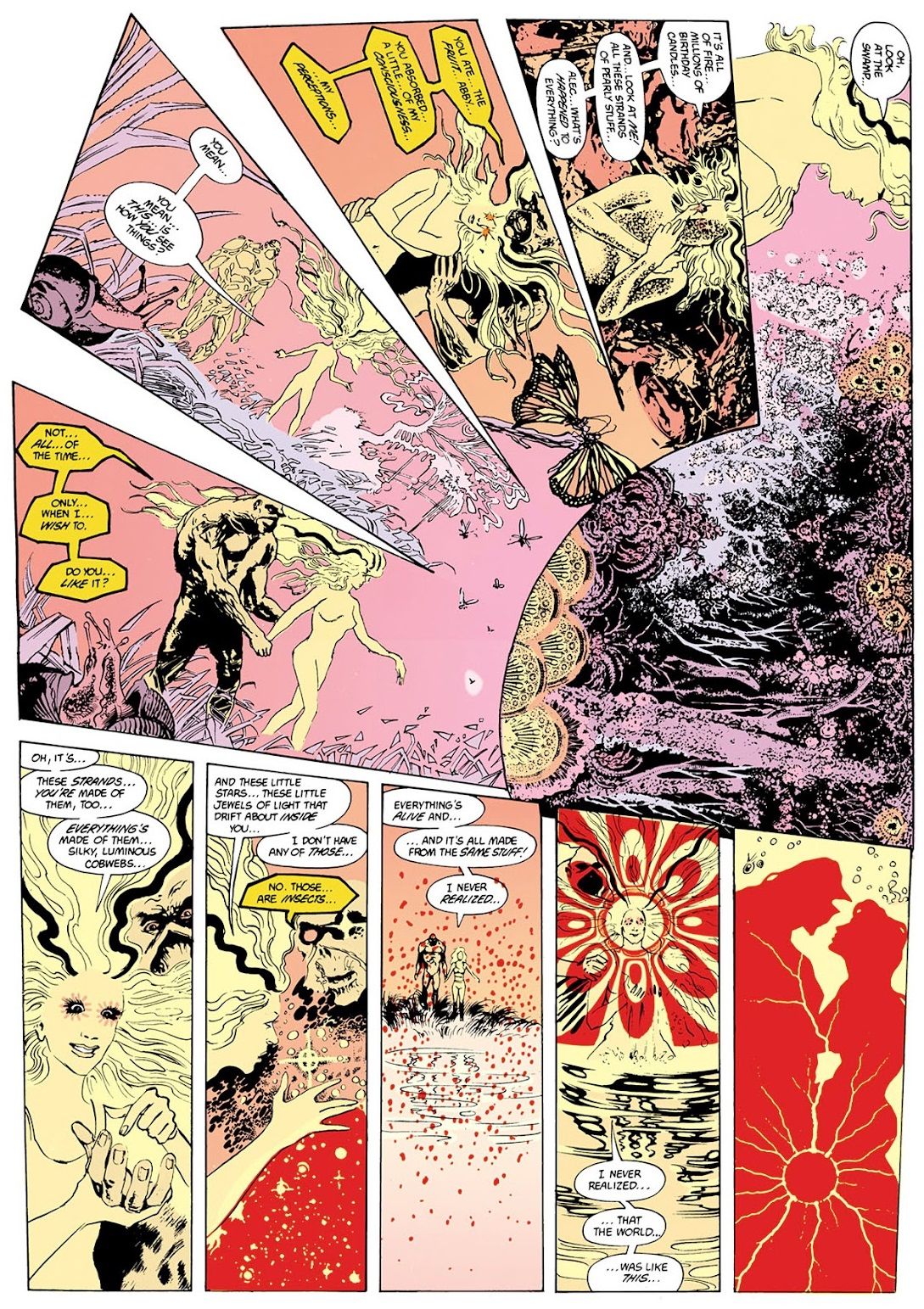

Throughout his run, Moore would tell deep character-based stories, most notably the relationship between Swamp Thing and Abigail Arcane. The issue where the two have sex is a stunning testimony to both Moore's skills as a writer (plus his artists, Stephen Bissette and John Totleben's skills as artists, of course). See how Swamp Thing and Abby have sex for the first time...

Once they've begun, their sexual experience is shown in a series of double page spreads. Here's one of them...

Also notable in Moore's work was when he would touch on the DC Universe, and give us drastically different takes on various famous superheroes. Moore's early work with the Justice League in an issue of Swamp Thing informed pretty much every modern writer of the Justice League. During his run, Moore also introduced John Constantine, who would be Swamp Thing's guide on a number of stories (more accurately, he would con Swamp Thing into getting involved in stuff).

Without Moore's Swamp Thing, we likely wouldn't have seen Vertigo and all the comics that spun out of Vertigo, or if we did see them, it would have taken a long time to get there, so its influence is massive.

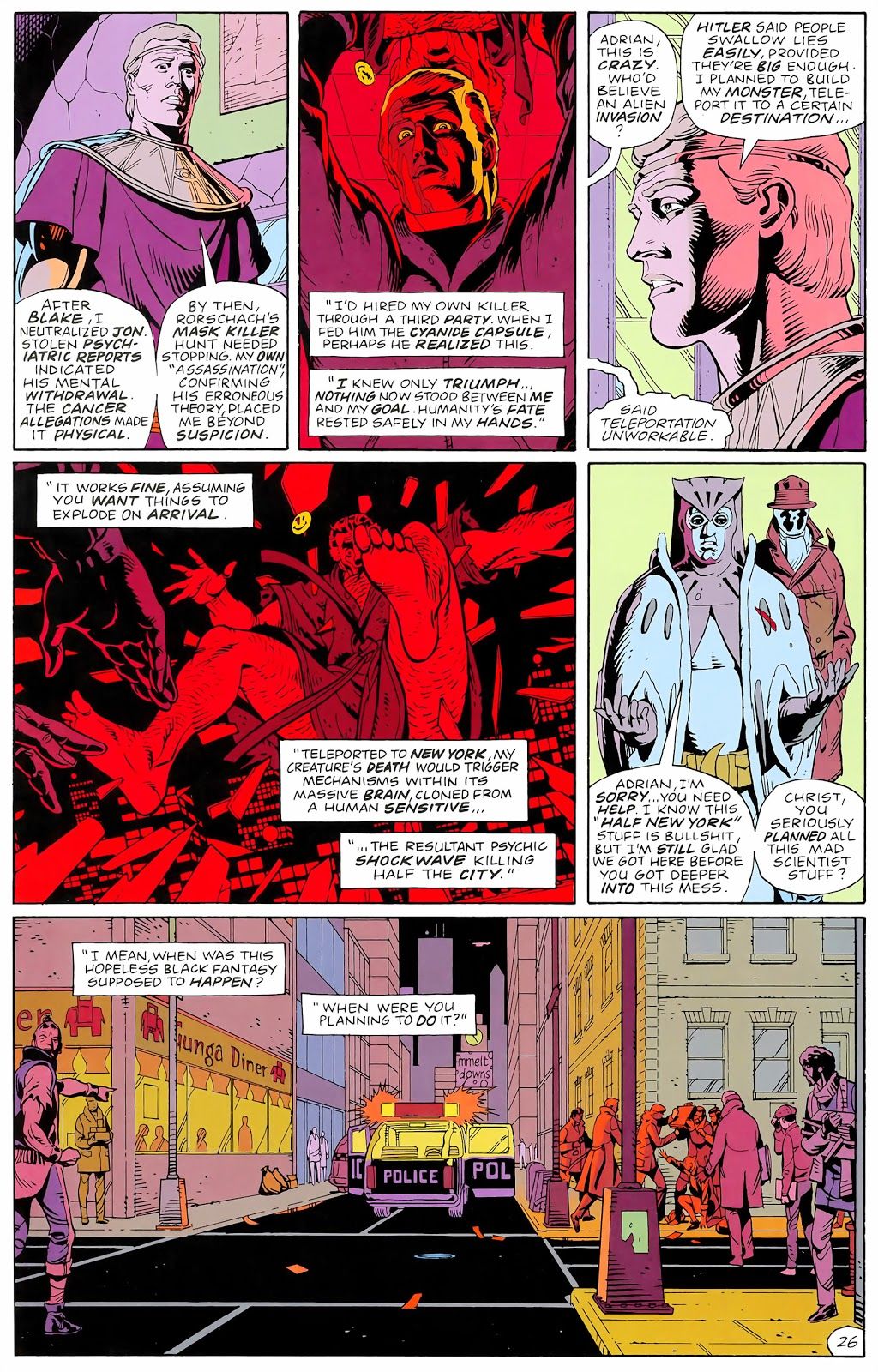

Towards the end of his Swamp Thing run, Moore began what has become his most famous work, Watchmen, which he created with Dave Gibbons.

A remarkable aspect of Watchmen is the fact that, past the fairly straightforward plot about an older superhero getting murdered, with his former teammates investigating his murder only to find out that it is all tied to a mysterious conspiracy, there is just so much detail and nuance. You can examine a single scene and get something new out of the scene practically every time you read it.

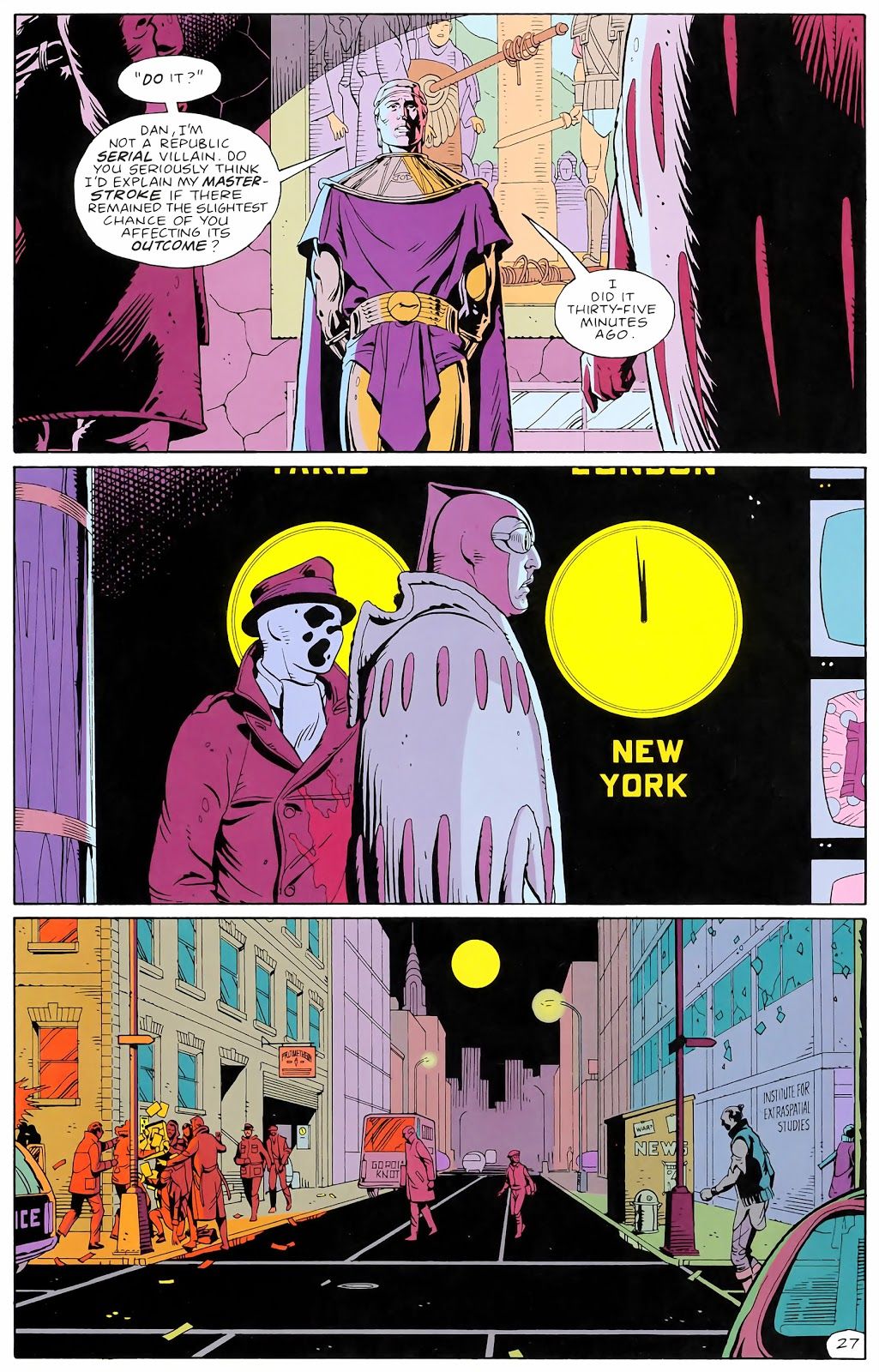

And that’s even counting all of the famous scenes that are awesome just on a straightforward reading of the book, like Ozymandias’ famous “I did it 35 minutes ago” line...

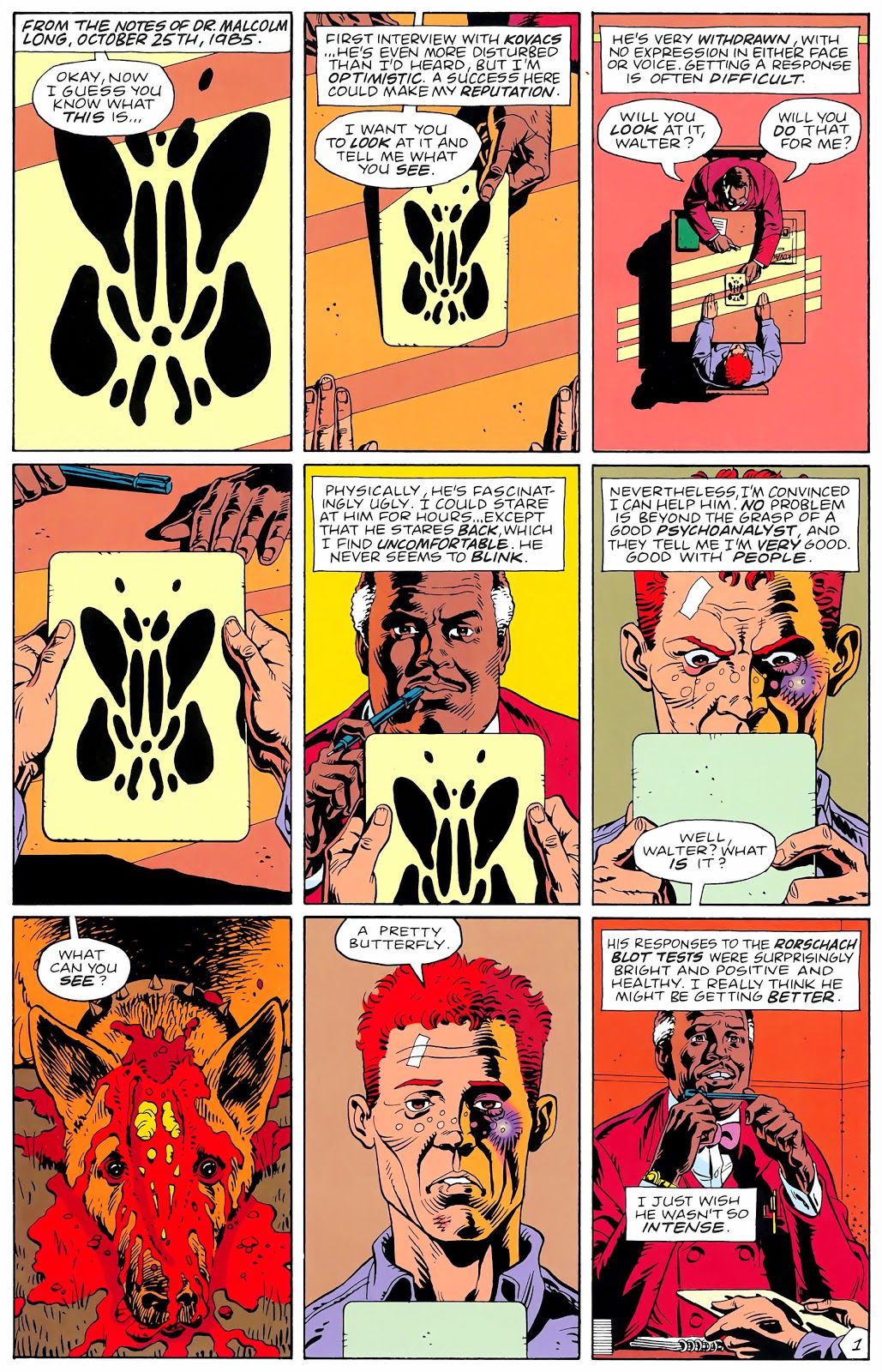

or Rorschach's first meeting with his prison shrink...

Watchmen was a masterpiece of comic book fiction, both in story and art – and decades later, it is STILL influencing comic book writers.

Moore didn't stop there, of course, he wrote the classic V for Vendetta (about the classic question - "Where would you rather live in - a fascist state or a state of anarchy?") and then From Hell (a tale of Jack the Ripper).

At the turn of the century, Moore debuted a series of new projects for Wildstorm and they were all excellent, from League of Extraordinary Gentleman (about a team made up of literary characters) to Top 10 (about a police precinct in a city filled with superheroes) to Promethea.

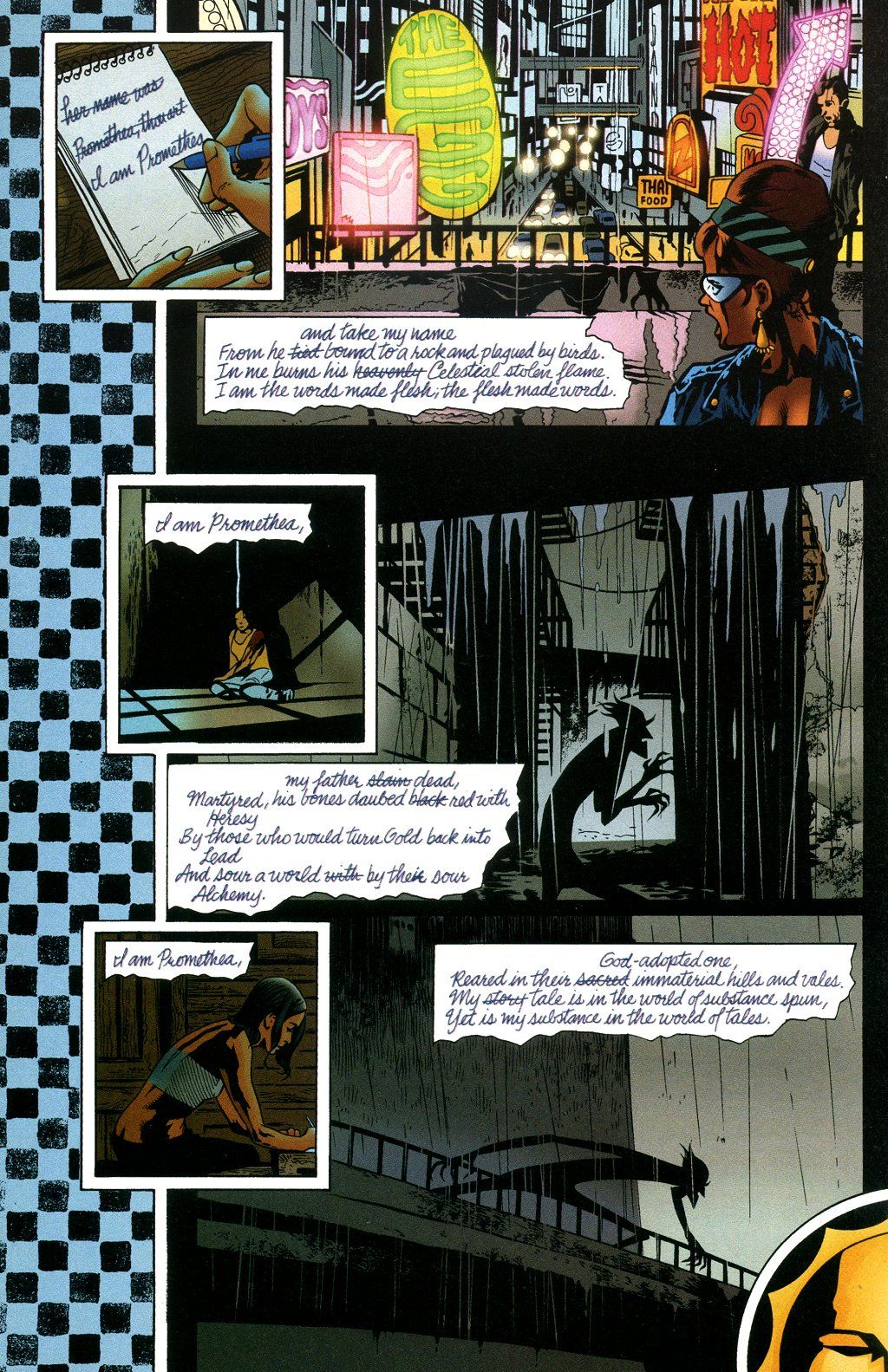

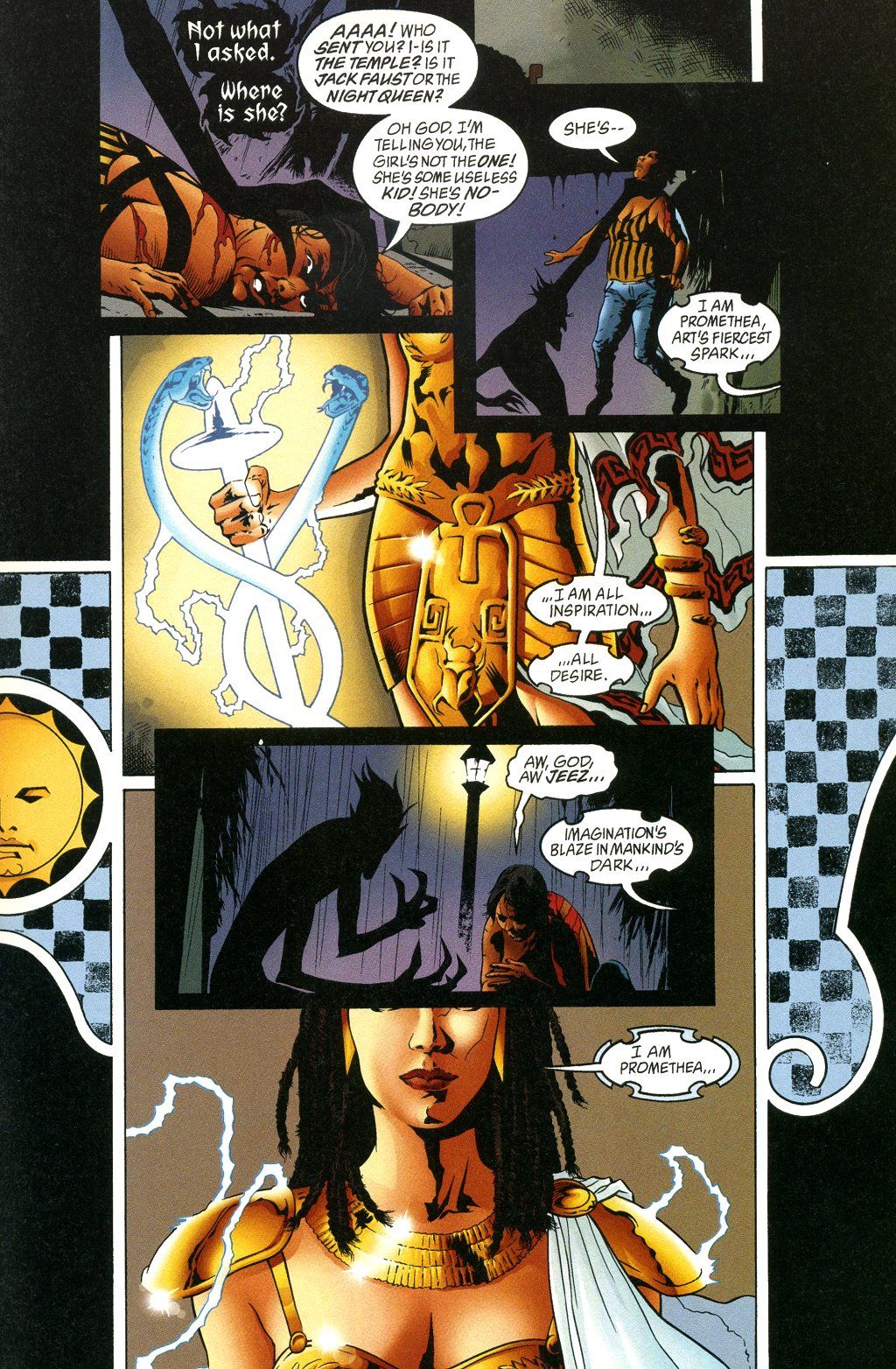

Promethea was an extremely interesting comic in the way that it was such a malleable concept that writer Alan Moore himself used the book to tell two dramatically different types of stories, all ably aided by the burgeoning artistic brilliance of artist J.H. Williams III, who went from being a strong artist to being one of the best artists in the entire comic book business.

Promethea was a young girl who was taken by two Gods into "Immateria," a land of imagination, where she continues to exist as a living story. She can appear on Earth when someone calls to her by writing about her - when someone does so, either they (or their muse) can BECOME Promethea.

That is what happens to student Sophie Bangs, who becomes Promethea, and soon gets caught up in the crazy superhero world and the much larger world of Immateria.

Here is her writing a poem to BECOME Promethea...

The first book or so of Promethea is heavily influenced by literature, especially as Moore takes us through the Prometheas of the past, including a poet, a cartoonist, a book cover painter and a pair of comic book writers.

Then Moore used Promethea to take the reader on a journey through the Sephiroth of the Qabbalistic Tree of Life, where Moore more or less uses about 15 issues of Promethea to give a series of lectures to the readers about philosophy. Williams really shines during this run, as Moore gives him a whole lot of strange things to draw.

After this storyline ends, we're treated to an extended storyline about the Apocalypse, which also signaled the end of Moore's America's Best Comic book line, so Moore used this storyline to say goodbye not only to the ABC line of comics, but also to the characters within them.

It all culminates in a stunning final issue, which can be read as a 32-page comic book, but can also be read by taking out the pages and arranging them to form two posters (back to back).

Moore did a number of other League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series, before ultimately deciding to stop working in comic books period, choosing instead to focus on prose work.