Have you ever heard the expression, "If a thing is worth doing, it's worth doing well?" Have you heard about DC Comics' He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, whose first six-issue miniseries was just collected? Have any of the people involved with the creation of those comics heard of that expression? Because from the results, it sure doesn't seem to be the case.

The comics are poorly made -- among the worst I've seen produced by an industry-leading publisher -- but they're bad in a very particular way.

They aren't unreadable; I made it all the way through He-Man and The Masters of the Universe Vol. 1 without giving up. If pressed, I'm sure I could come up with some worse, more poorly made comics from DC in the recent past, but I might have difficulty thinking of worse comics from creators of such a relatively high caliber as some of those involved with this project, or an example of a series so bewilderingly bad.

Seemingly rushed through production like a term paper written the night before it's due, many of the comics' problems appear to originate with there being just too many creators working too fast and with little communication to meet a particular deadline. But,the funny thing is that it's just a He-Man comic that no one in the comics-reading audience seemed particularly excited about, let alone interested in.

So it's hard to imagine a reason DC decided to steam ahead with its creation to meet an arbitrarily chosen deadline before, say, nailing down a single creative team. Put another way, this is a bad comic book, and I can tell you what makes it a bad comic book, but I can't hazard a guess as to why the people responsible for it made the decisions they did that resulted in it being so bad.

The comic is, of course, the latest incarnation of a multimedia property that began in 1981 as Mattel toy line before spawning a popular and fondly remembered early-'80s animated series, a 1987 live-action movie, a 2002 revival of the cartoon and toy line and, of course, comic books, previously published by DC, then Marvel's Star Comics line and, far more recently, Image Comics and MV Creations.

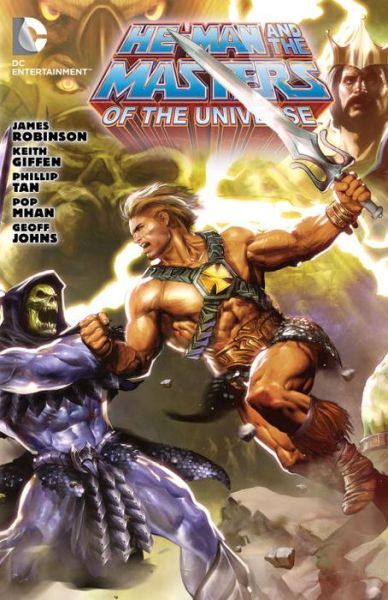

Although not part of DC's New 52 line (although a crossover is imminent), He-Man suffered some of the too-common creative team problems that have plagued DC since the relaunch. Writer James Robinson, penciler Philip Tan and inker Ruy Jose were originally announced as the creative team, although Robinson only wrote a single issue before Keith Giffen took over (the pair share writing credits on Issue 2, while the rest of the series is all Giffen).

The art team turned out to be something else entirely: The six issues are penciled by Tan, Howard Porter and Pop Mhan, three artists whose styles have little in common, with half of the issues penciled by more than one of the above, and the other half drawn either by Tan or Mhan, start to finish.

As for inkers, there are eight different artists in that category for these six issues, with as many as four inkers on a single issue.

With so many cooks in the kitchen, it's little wonder how bad the comic looks, with the often dramatically redesigned characters sporting elements that come and go depending on the panel and, in a few particularly depressing instances, the artwork contradicting the script (one issue ends, for example, with one of the heroes having been shot through the shoulder with a crossbow bolt, but at the beginning of the next issue, the wound is gone; later the protagonists talk about the strange writing they see on a wall, yet the artist has drawn smooth, writing-free walls).

The trade opens with a short story by Geoff Johns, Porter and John Livesay featuring an original Johns addition to Masters of the Universe, one he apparently created as a child, which, given the child-like names and abilities of the characters, is actually kind of perfect: Sir Laser Lot. This brief adventure begins in the distant past, and ends with Sir Laser Lot and a mysterious skull artifact being summoned to Skeletor's throne room.

From there, the series begins in earnest. Skeletor apparently has taken and occupied Castle Grayskull and utterly defeated his enemies — the Masters of the Universe — by wiping away their memories of their past lives and scattering them across Eternia. He-Man is now Adam, a simple woodsman, whose only clue to his heroic identity are his vivid dreams. One day an improbably colored falcon named Zoar leads him out of the forest, and, as he follows it, he slowly recovers certain memories (like how to fight, mainly) and picks up allies, first and foremost Teela, who is a slave in a desert town, and with whom Giffen has him bicker like they were in a barbarian screwball comedy (Man-At-Arms shows up in the second half of the series).

As they make their journey, they run a gantlet of villains, each of whom Skeletor has instructed to kill Adam, and each of whom spectacularly fails: These are Beastman (whose redesign seems to occur somewhere between Issue 1, when Tan was drawing him, and Issue 6, when Mhan was), Trapjaw (who wears a robe and scarf around himself for dramatic reveals, and effects the changing of the interchangeable weapons on his hand via some sort of glowing magic lizard), Mer-Man (who now has a tail, except when the artists forget to draw it, which is about one-third of the time) and finally Evil-Lynn (who rules a volcanic island and is here played as crazy as a loon). After each villain has been bested, their true identity is recovered and He-Man and Skeletor meet in battle.

If one can somehow forgive the book's failing of the most fundamental aspect of comics — telling a story through words and pictures — and its rather wretched art (and I consider myself a fan of Porter and Mhan!), and focus on it purely as a script, it's still not a very good one. It demands a pretty thorough working knowledge of the main characters and their conflicts (no problem for this 36-year-old, who started playing with He-Man figures at age 4) and apparently picks up on an already-in-progress story involving Orko having gone bad. Whether that occurred in some other DC MOTU comic, or continues from the Image or MV series isn't mentioned; I would expect a book with "Vol. 1" in the title to be the start of a story, though, and it is possible that Giffen includes that as simply a teaser for plot points to be explored in the ongoing that follows this miniseries.

The series is merely a half-dozen fights between our heroes and barely introduced, increasingly tougher villains, until the book simply stops with a cliffhanger ending promising a different direction than the one we were just introduced to. It's basically a long walk around a toy box, with the names of those toys occasionally being shouted out.

In addition to creative team chaos and redesigning for redesign's sake (usually for the worse), the book has another thing in common with the current direction of the publisher's main line: It's clearly targeted at adults who grew up with this stuff and expect it to have matured with them, rather than to remain appropriate for the age group it was originally intended for.

So it's rather violent for a He-Man, although the artists occasionally neglecting to draw blood or depict wounds tones it down quite a bit. Even still, this is a comic in which Teela impales Mer-Man through the chest from behind (don't worry, he's fine), Skeletor snaps The Sorceress' neck after months or years of torturing her and, in the climax, He-Man punches Skeletor so hard his lower jaw flies off and a pint or so of blood splatter flies out of his ... skull ... holes?

I haven't thought a lot about Skeletor's biology in the past, oh, 30 years or so, but apparently his skull is full of blood and, if you punch him hard enough, it's like squishing a jelly doughnut.

I've heard the comics — which so far include at least three one-shots and an ongoing series, with Giffen the sole writer — do get much better after this miniseries. But then, I suppose they'd have to, wouldn't they?

I'm certain there's value in the He-Man intellectual property, and it's well worth DC's time to pursue developing it. What I'm uncertain of is why the publisher had to do it when it had to do it, quality be damned. A publisher that expects its audience to wait seven issues or so for a comic book series to get any good at all is either cursed with shortsightedness that will always limit its success, or blessed with the most patient and forgiving audience it could hope for.