“You can tell I’m still making sense of it myself.” So says Sammy Harkham of the eighth volume of his landmark anthology series, Kramers Ergot, at one point during our lengthy conversation about the book. And indeed, Harkham’s side conversation is characterized by strategic pauses, halves of sentences that trail off and are abandoned as Harkham retreats, rethinks, and rearticulates. Despite his ebullient cadence – Harkham’s as great a talker as he is a tweeter – it’s quite clear that the amount of thought he put into this comparatively slim and quiet volume of his once-overflowing and raucous art-comics anthology is nearly overpowering.

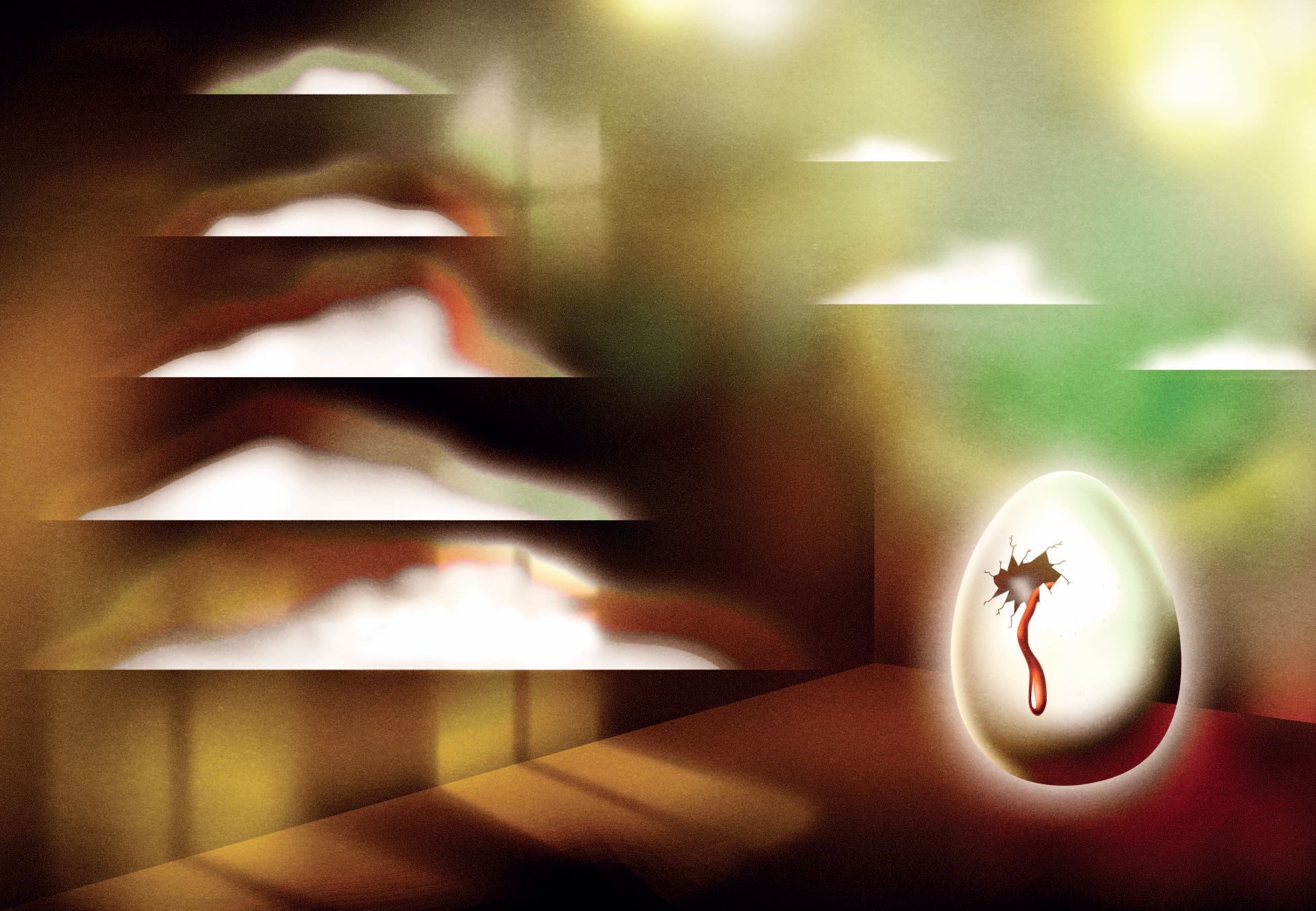

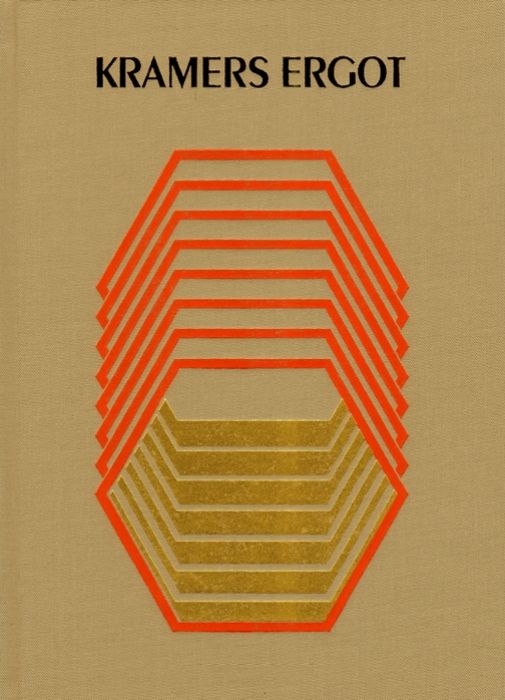

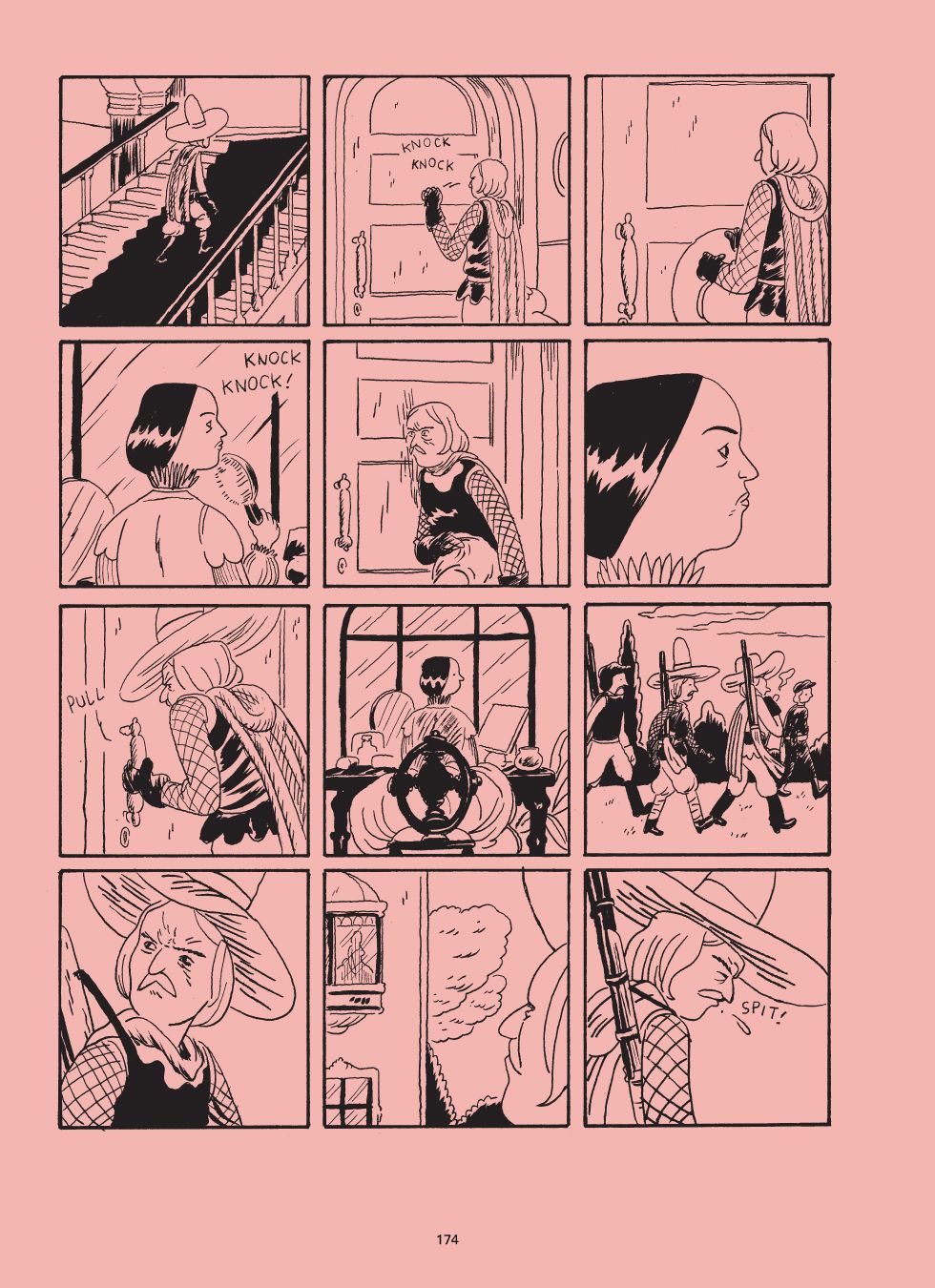

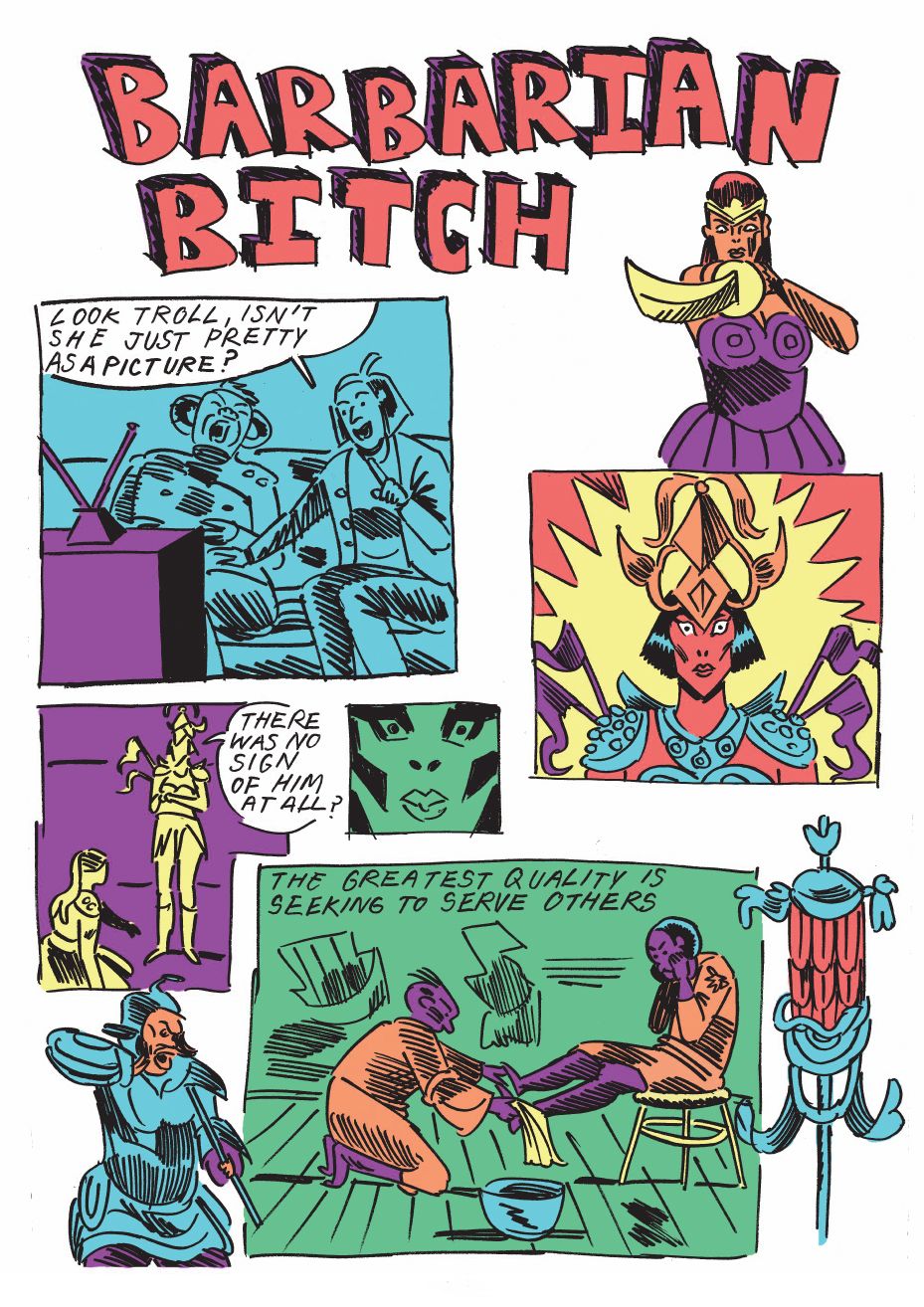

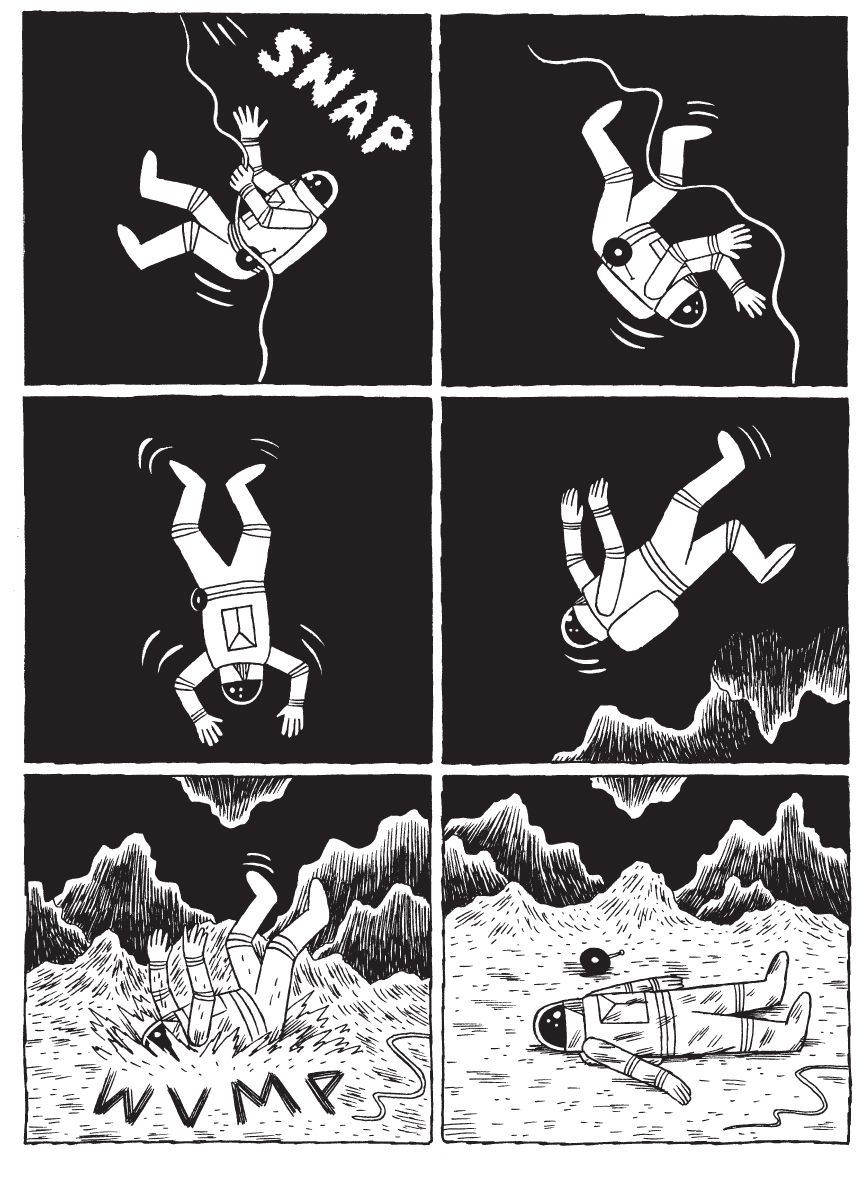

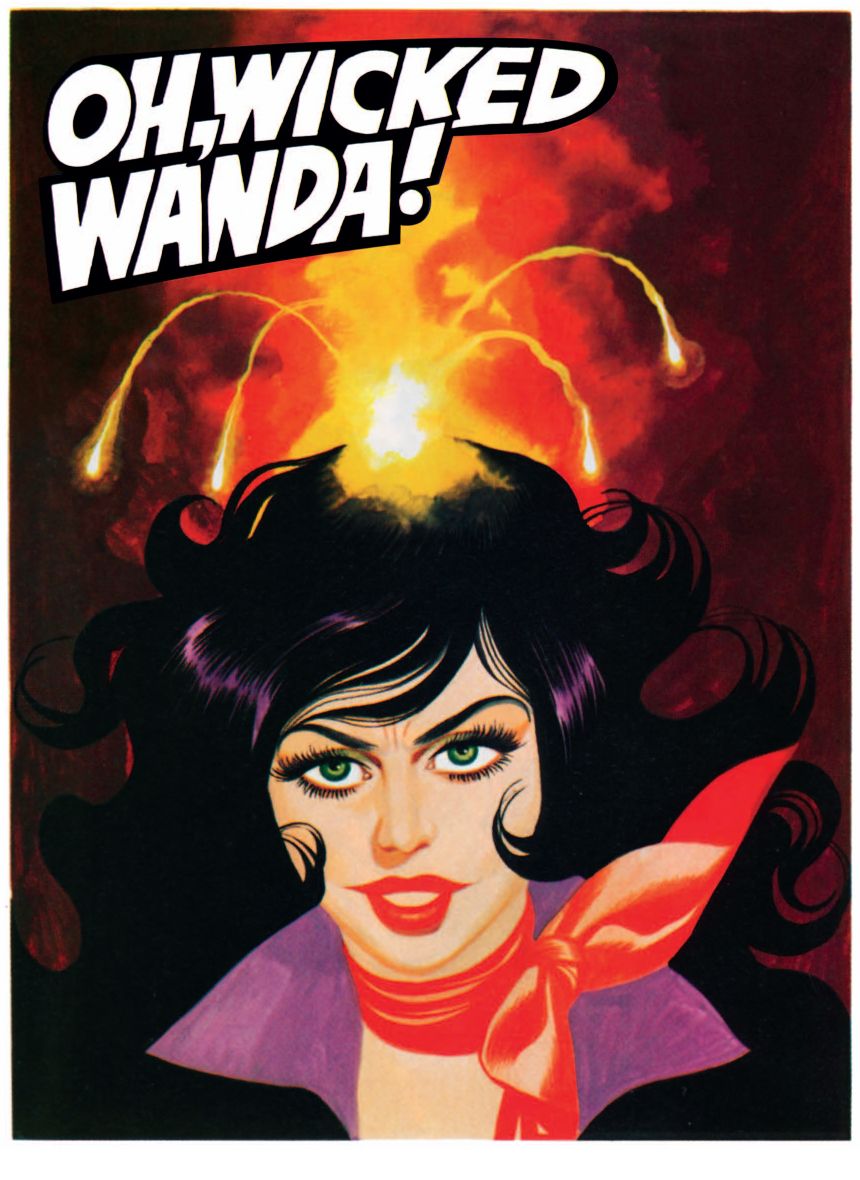

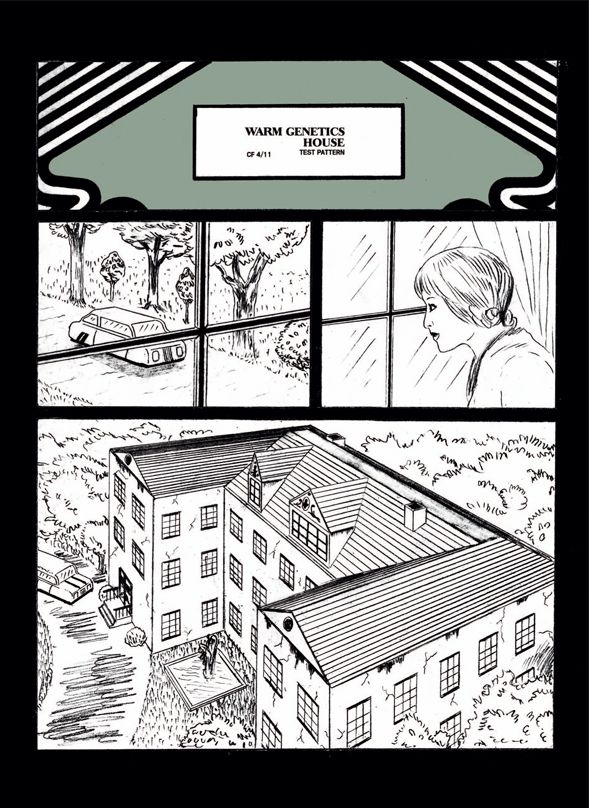

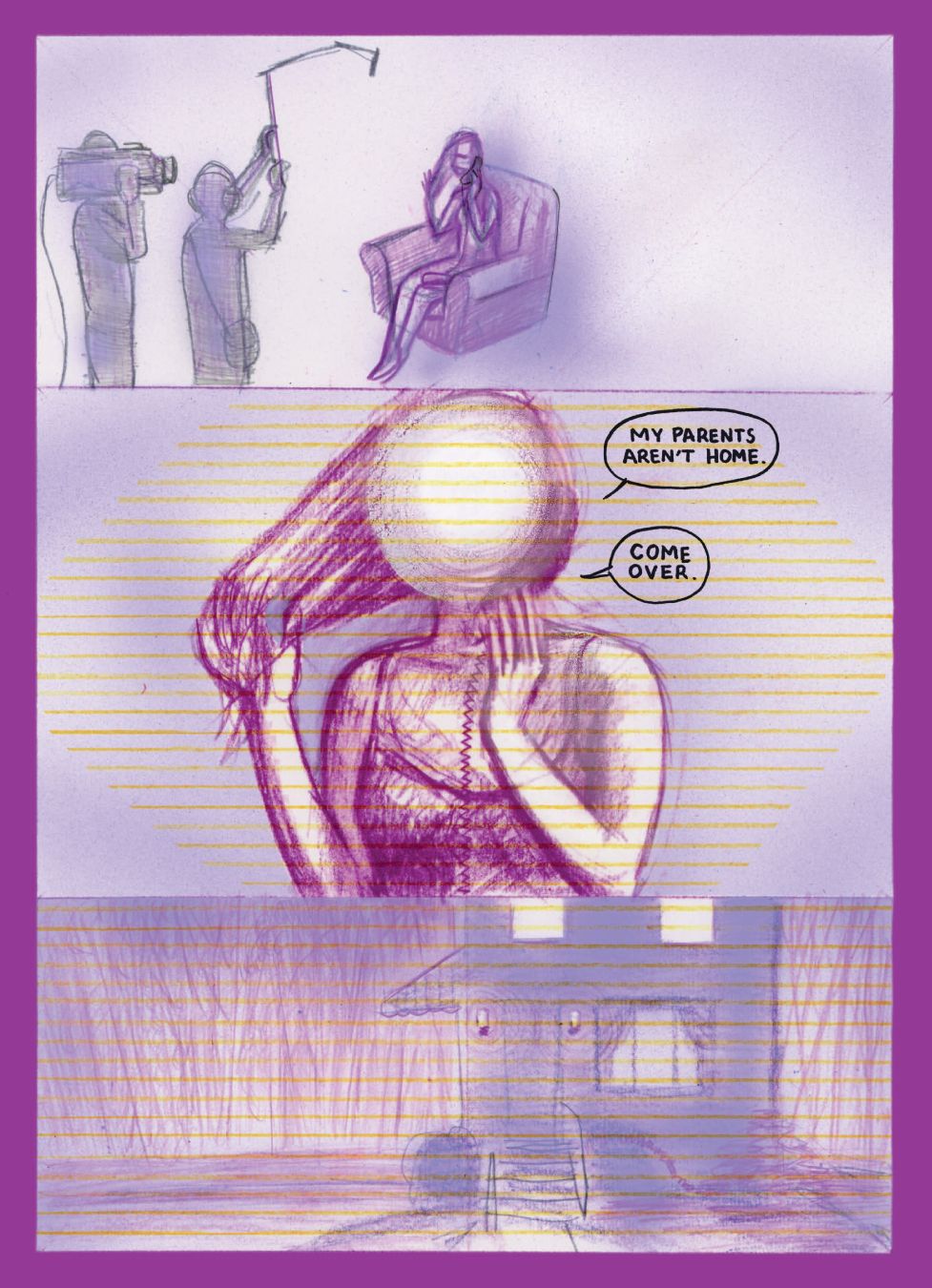

So is the collection itself. Despite featuring a much smaller roster than previous volumes in the series, and despite a much less “noisy” visual aesthetic than that which has characterized the series since its phone book-sized fourth volume caused a sensation upon its release at the MoCCA Festival in 2003, Kramers Ergot 8 has an intensity that’s tough to shake. Contributors like C.F. (aka Christopher Forgues) and Chris Cilla craft uncomfortable but undeniably erotic sex scenes, which sit next to grim science-fiction parables from Gary Panter and Kevin Huizenga and gruesome horror tragedies by Johnny Ryan and Harkham himself. Fine artists Robert Beatty and Takeshi Murata contribute pieces as visually vibrant as the stories of crime and desire from Gabrielle Bell and the team of Frank Santoro and Dash Shaw are bleak. A cheekily provocative introductory essay from musician Ian Svenonius and a massive selection of racy reprinted Oh, Wicked Wanda! comics from the pages of Penthouse prove perplexing – but it’s a good perplexing, because it forces the reader to consider just how fingernails-on-a-chalkboard effective the rest of the volume is at discomfiting them.

With the book on its way to stores from PictureBox Inc. in a couple of weeks, Harkham took an hour before picking his two older kids up at school to talk about this very personal project. We started off talking about our respective babies; fitting, then, that by the end of the interview a fascinating picture emerged of what Harkham wanted Kramers 8 to be that proved every pause along the way was a pregnant one.

Sean T. Collins: Kramers Ergot 8 debuted at the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival in December, but your third baby debuted not long before that. That had to be a challenge.

Sammy Harkham: Knowing the baby’s coming, you work knowing that when that baby comes, things are gonna shut down. The book only got finished mid-September, and then the baby came. It was funny, because I drew my comic [for the anthology] when the book was done, basically. I thought, “I’ll do a simple issue of Kramers, I’ll do a story for it, and then I’ll get back to Crickets.” But editing, for me, is like working on my own book, as if it’s fully just me. I’m thinking about it day and night, and it’s hard for me to then think of a story within that if I don’t already have one that I’m working on. So at a certain point I decided I’m not going to be in the book. Then it was clear I needed to be in the book, because I wanted a very particular kind of story in it [laughs]. “I guess I’m gonna have to do it.” It was a flurry of activity August into September, then it was done, then the book was done, and then I was just…breathing, you know? But I felt like, “Oh man, I really should be working right now before the baby comes.” But since the baby came I’ve still been doing stuff. You know what it’s like: a lot of tricky hours, and getting used to weird working habits. You work for five minutes, but you try to make it a good five minutes. You try to break it up. And I try not to lose my temper. I get resentful of the people around me when they’re asking for my help and I’m in the middle of something. [Laughs] If I’m in the middle of writing or drawing something, I wanna finish the thought. So I’ve got to think of those Dalai Lama tweets I read earlier in the day. [Laughs] You’ve got to get into the headspace where you’re malleable in that way, you’re flexible.

But Kramers was late this year. Nadel wanted it in July, but I’ve never been able to deliver that book on time, never. This one was particularly hard because there were so few contributors, so I couldn’t lose anybody without it affecting the whole thing. Whereas in previous issues there are so many people that unless it’s a really big strip – it’s a shame to lose anything, you don’t want to lose anything, but you can. You can lose a one- or two-pager. But with this, if CF is running late, there’s nothing we can do. I told [PictureBox Publisher Dan] Nadel that up front: “I hope to get the book done on time, but if Panter’s not ready, if Christopher’s not ready, if any of these people aren’t ready, we can’t do anything.” [Laughs] We’re at the mercy of them, really.

Collins: Was that something you factored in when you approached people?

Harkham: Not at all. Not at all. With this one, I was thinking of people who drew…I wanted a certain uptight energy, a certain rigidness to the work. That was a guiding principle. Then the people who don’t draw super-tight or super…I don’t know what the word is, but there’s a certain energy was going for, and the people who don’t necessarily conform to that, I thought, in a way define the book by what they aren’t. Leon Sadler, to me, almost defines the whole book by being so loose, because he really sticks out in sharp relief. Same with Anya [Davidson]. Those are the two people I think of as being kind of different stylistically, Anya and Leon.

I just wanted to get away from…I don’t know. [Pause] It’s a very hard book for me to discuss or to verbalize, because so much of it was intuitive. I wanted to do something that really felt different from what other Kramers were. It was really about thinking of a tone, and trying to think of who fits within that tone, and trying to create a vision of comics that maybe doesn’t exist, but to pretend that it does. Or to create it. Or to give the impression that it’s always there, but I really have to use spit and rubber bands to put together and give it that veneer.

Collins: The tone that emerged for me was a sad one. There was a melancholy to it. Maybe that what emerged for me from its spin on the sex and horror comics that are very much in the air right now. But beyond that, the strip I return to mentally is Kevin Huizenga’s cover version of a golden age sci-fi strip, which I found crushingly sad.

Harkham: It’s bizarre, right? It makes you really think about – tell me if you disagree, but you think of the guys who made the original strip, right? I mean, what is this? What is this strip? You’re right, I totally agree with you. It’s a really sad strip. It’s a very bizarre strip, and it’s a weird thing that someone did that comic knowing that the only people who were going to read it were children. It makes me think of Frank King working on Gasoline Alley, this idealized vision of what he wants his life to be, of him living with this son who in reality is very far away from him. Comics are often like that. Because of the nature of the work, it is often about escaping into a space and letting things live and breathe that in reality can’t exist. That’s often the impression on the last page of a Kim Deitch comic. [Laughs] I feel like he’s realizing that it’s over, and he’s like, “I kinda want to live with these pygmies forever in this miniature city that doesn’t exist.”

Collins: Now that you mention it, there’s a sense of loss to the book, too. Maybe it’s in the way the the sexy stuff sits against the horrific and angry and sad stuff, which spoils it or something. I think of Chris Cilla’s story, in which a sexual liaison is interrupted by a little kid who says, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell anybody.” It felt like something had been ruined. I came away from the book feeling… [sighs]

Harkham: Did you like the book?

Collins: I did! Oh yeah, I did. There was stuff that I struggled with…

Harkham: I ask that honestly. I honestly have no idea what reception the book’s going to receive from people. I don’t know if they’re going to take to it. And I’m open to that, I’m fine with that. I ask that question with my eyes open, not in a defensive way.

Collins: A lot of the stuff is very much in my wheelhouse. I love the direction that Johnny Ryan continues to go in.

Harkham: That strip is beautiful. It’s an ode to commitment and love. It’s a really rich story. Including Johnny in a book like this, where I wanted things to have a certain amount of restraint and emotional coldness, not the usual flop sweat and a gag every second – with Johnny, it was all about talking to him about the slow burn. I know Johnny well enough to know he’s really well read and a really smart writer. We’ve talked a lot about story and literature. It was exciting to bring him into this, knowing that when I mentioned his name to the other contributors, they were like “Huh, he doesn’t necessarily sound like a great fit for this,” and he really delivered. That strip is amazing. He doesn’t tie up all the loose ends, he doesn’t tell you exactly what’s going on, but there’s enough ambiguity and enough focus. I think it’s a really beautiful comic.

Collins: It feels like an answer to the Huizenga strip, too.

Harkham: That’s interesting. [Pause] That’s really interesting. [Laughs] Oh my God, I hadn’t thought about that!

Collins: These explorers searching for love—

Harkham: Looking for love, yeah!

Collins: --and finding these nightmares they choose to embrace.

Harkham: Cool. My struggle with Kramers is always looking at it so intensely and never feeling like it’s good enough. You want things to be better and better. I’m really hung up on narrative, so I always want better stories, and it takes me a bit of time to stand back from it and come towards it a couple months or years later and go “Oh, that’s a good issue.”

Collins: Kramers 4 had such an atom-bomb impact, and I think what a lot of people took away from it was the non-narrative material – the Fort Thunder contributions, the collage material. But the series has had a parallel thread of full-fledged short stories all along. Were you expressly trying to point in that direction with this new format?

Harkham: I wanted each contributor to do a somewhat meaty amount of material. So when you think about that—I broke it with Leon, but again, that helps define the rest of the book by having his section be all kinds of little bits and pieces. But besides Leon, I wanted each person to do a substantial amount of pages, or if not a substantial amount of pages then something that felt substantial. Comics are funny like that: A two-page strip can live in your mind like a 500-page book. So it wasn’t necessarily page count—I just wanted it to be really strong material. And it’s always a struggle to get that out of people, but with this one it was more like seeing if people could make a serious commitment. Most of those strips are over eight pages. Gabrielle’s is shorter and Kevin’s is shorter, but they’re all around eight, and beyond that. It’s a lot to ask of people, especially these days, when all the people I was working with have other projects.

Collins: The other week I reviewed the final issue of Mome for The Comics Journal, and to open the review I listed a bunch of anthologies that had come out over the past couple years, off the top of my head. There were two dozen easy. It’s a much more heavily anthologized era right now than it was when Kramers started.

Harkham: I think there’s a real need for it.

Collins: Why? And was that something you were considering when you were putting #8 together?

Harkham: To answer the first part, there’s always a need. People need an outlet for their work, and online is one thing, but having it in print is another. Comics lend themselves to short form, so it makes sense that there are going to be a lot of anthologies. To me, doing another issue of Kramers was more about…When approaching any issue, it’s always like, “What do I want to see? What do I feel a lack of as a reader?” I do read a lot of comics. I feel like I’m so heavily engaged with comics—too much, sometimes! [Laughs] Probably to an unhealthy degree. It’s crazy. You’re a writer of comics, so you know. You’re deeply involved as well. So it comes out of [thinking of] what kind of book I’m excited to see. Sometimes I feel like “Oh, everyone’s doing the work that I want to see.” Then there’s times like this, where there’s a kind of comic I want to see and it doesn’t exist, so I’m going to make it: “I want to present people’s work in a certain way that I don’t see it presented in. I want a context that I don’t see out there.” And starting to build from there.

That’s why I wonder about how people are going to respond to it, because to me, it doesn’t feel like there are many books like it. When Kramers 4 came out, there was a lot of resistance from within comics to that! [Laughs] I was still posting on the TCJ.com message board at that time. I was 23 and commenting on that board all the time. When people started talking about that book I was really excited, until everyone started shitting on it. [Laughs] But then people started sticking up for it. I mean, I know now that that’s always a good thing, when people dislike something enough to want to talk about it. That means it’s connecting on some wavelength, and that’s important. But with this, I don’t know how people are going to take to it. They might think it’s pretentious or they might think it’s too dry or something.

Collins: I bought Kramers 4 at MoCCA when it debuted, and I was on the TCJ messboard then as well. I remember the argument was like, “Is this comics? This isn’t comics!” That book won that argument so completely that it’s not even an argument people have anymore, at least not among art comics readers.

Harkham: People are over it. At the time I didn’t think the book was that far out. I thought it was a very normal thing, coming out of all the [pioneering art-comics publisher] Highwater books at that time. Don’t forget, [Marc Bell’s] Shrimpy and Paul had already come out, and [Mat Brinkman’s] Teratoid Heights came out either around the same time or just after, but Brinkman was doing work. All those people were doing work that was available, so to do an anthology including all those people did not feel like I was necessarily bringing anything new to the table. I was just trying to make a good collection.

I never focus on showing people stuff they’ve never seen before, because I think that’s a really shallow approach. It won’t yield so much great work by focusing on what’s new, what’s hot, what are people going crazy about this month. Comics people are very fickle. You mentioned that whole thing about horror and sex right now. Ben Marra started doing his thing the last two years, Michael DeForge, obviously Jonny Negron—there’s a certain energy in the air where people are getting really into doing unironic genre-based work, and it feels fresh. But in a year from now, maybe the hot new thing will be like Peepshow. It’s not a fickleness, but because the alternative comics scene is so small, there’s a lot of turnover, a lot of moving forward about what’s exciting. I try to avoid thinking in those terms.

So to go back to what we were saying, Kramers 4 was to me a very normal anthology. It was a big anthology, but I didn’t think I was necessarily bringing that much to the table. With this one in some ways I feel the same. But just seeing the response to the last issue… When that book got announced, the way people took to it, the negative comments that people had about that book – [they were] saying things I would never have thought of if I hadn’t read someone saying these things online, about making a book that was elitist. I guess I’m used to people second-guessing Kramers and putting a lot of their own baggage and issues into the work. Which is normal. Art goes halfway, the reader goes the other half, always. So if people want to look at a book and take the most negative view of why certain decisions are made, then that’s their prerogative, and I’m comfortable with that. So with issue eight, I know I wanted this book to be a certain way, and people may not take to it, and I’m okay with that.

I listened to the roundtable conversation [about the best comics of 2011] on Inkstuds [featuring critics Robin McConnell, Tim Hodler, Joe McCulloch, and Matt Seneca] and I thought that was really interesting. I’m listening to them talk about the book…[Laughs] I respect all those writers, but at first I was like, “No, I disagree completely. That’s fine, whichever way they’re taking to the book is fine, but I don’t agree with what they’re saying.” But as I listened to it, I realized they were teaching me something about the book. In a way, I was learning about what I was thinking. I realized they’re kinda right about a lot of their opinions about the book.

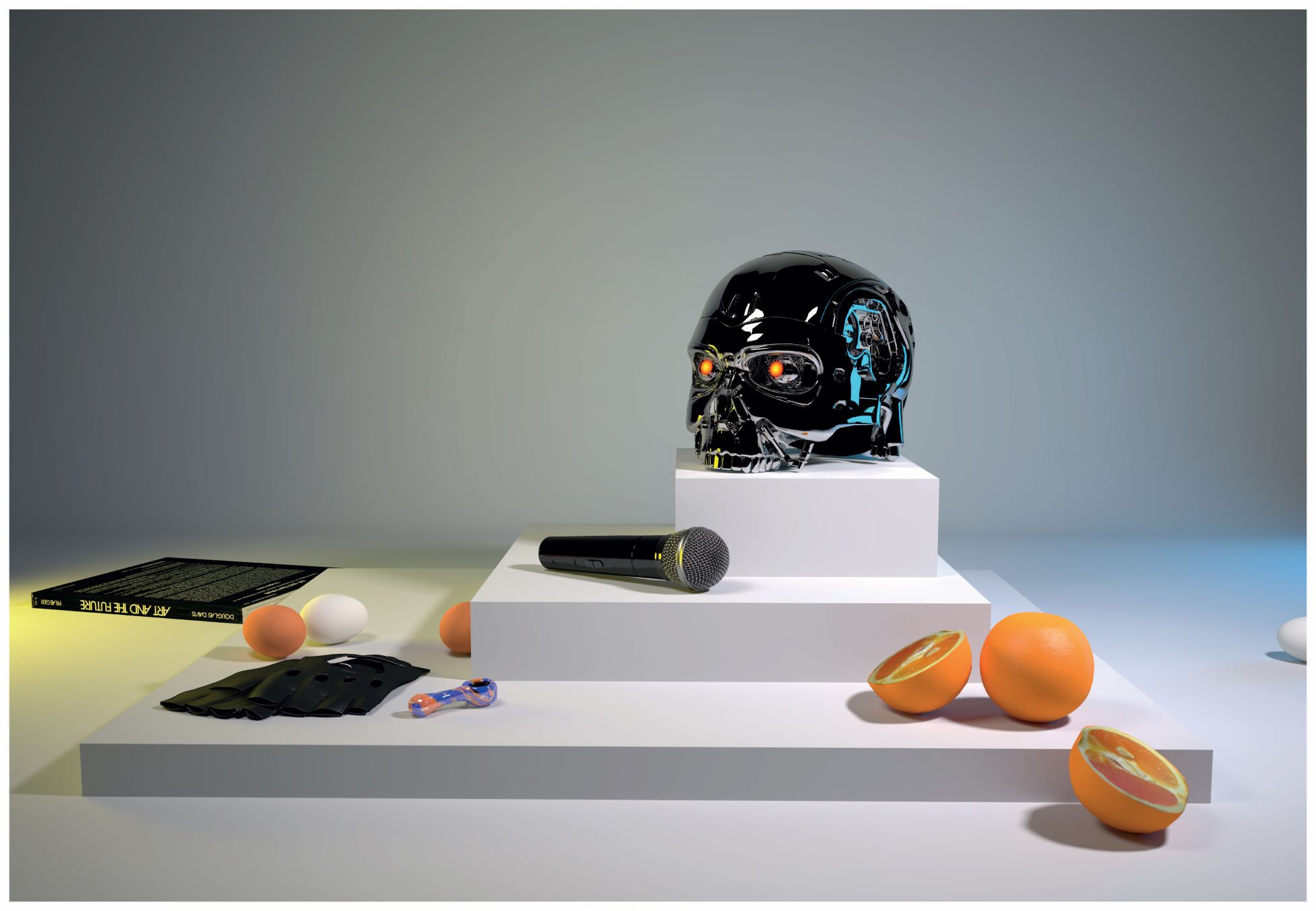

Collins: The reason I brought up the debate over #4 actually ties into what I got out of that roundtable myself. Looking at #8, I have no problem processing the art from Robert Beatty and Takeshi Murata. I’d compare the opening stuff from Beatty to the opening synthesizer instrumentals from 1984 by Van Halen or Music Has the Right to Children by Boards of Canada – it’s really appropriate that it’s called “Overture.” And the Murata stuff, the way it has this beautiful sensual vibrant feeling but depicts these weird, slightly sinister items of pop- and trash-culture detritus…I get what that’s doing there among these comics. The stuff I really struggled with were the intro from Ian Svenonius [Harkham laughs] and the Oh, Wicked Wanda! material at the back of the book. The Oh, Wicked Wanda! stuff looked gorgeous on that lovely paper you selected for it, but I didn’t really like them as comics. And there was just so much of it!

Harkham: [Laughs] I had a hard time cutting it down!

Collins: And the Svenonius—I just wasn’t ready for an introduction to a Kramers Ergot that ended with “ZAP! BLAM! POW!”

Harkham: [Laughs] I know – I’m with you, man, I’m with you! Have you read any of his writing?

Collins: I feel like I have, although I couldn’t tell you what it was. I have enough friends who are deep into his various bands, Nation of Ulysses or Weird War or Chain and the Gang depending on the friend, that I feel as though these things have filtered into me secondhand, though I couldn’t pinpoint exactly how or why.

Harkham: There’s a book that the record label Drag City released of his essays called Psychic Soviet that I really recommend. I’m only slightly aware of his music; I really know Svenonius as a writer. My only concern with including him was that for people who did know his music, it looked like we got some hip dude to write an intro – like getting a Morrissey to write an afterword, or Steve Albini or something. I was a little bit concerned just ‘cause it’s him. But as an aside, you should read his other essays.

Collins: Well, in that Inkstuds roundtable, Joe McCulloch made the argument that the Oh, Wicked Wanda! material at the end of the book was as if the Svenonius essay was saying “The prosecution rests!” The essay was about the way pop art nullifies and destroys art’s revolutionary potential, and here at the end of a book of underground comics you have this endlessly long, vaguely funny smut comic – choke on it. [Laughs] I wasn’t sure if I bought it, but he was able to contexualize them a lot better than I was.

Harkham: Yeah, me too. I think editing an anthology is not that different from making your own book, in that you gather bits and pieces that feel right and start making this overall thing. You don’t necessarily have a clear idea, you just know that you like these things next to each other. In the same way, when you’re writing a short story, you’re like, “Well, I’ve got this scene, and I don’t know what it means, but there’s something I’m really attracted to.” It resonates within you, something very simple – a guy barbecuing in the rain or something. [Laughs] You’re attracted to these little things and they all come together. I had some very clear ideas about why I wanted certain things, and then there are some things you’re unsure about. So listening to McCulloch talk about what he thought was very interesting. I don’t feel like it’s my place to say he’s 100% right, he’s 100% wrong – I just thought it was interesting. Once the book is done, it’s now owned as much by the readers as by me as far as what it means. I try to avoid getting in the way of that and saying “No, it’s here because of this.” I don’t necessarily want to effect how people read the book.

Collins: I’ve heard that from artists; it’s really interesting to hear it from an editor.

Harkham: Well, you know, I have my own feelings and thoughts about Oh, Wicked Wanda!, and I don’t necessarily want to smother the reader with my take on it. I’d much rather they engage the work. If I wanted to, I’d run little paragraph intros before each strip to contextualize why I like them in my own editorial voice, but I don’t feel like that’s necessarily an exciting book to read. Every book, regardless of whether it’s an anthology or by a single author, should have a certain amount of ambiguity and mystery and tension. The only time those things should be lacking – and it’s debatable – is in a work of nonfiction. That’s debatable, because some of my favorite writers of nonfiction bring a lot to the table where they don’t have all the answers. To tie it into comics, Dan Raeburn’s Imp #4 about Mexican comics – he’s wrestling with stuff, and it’s interesting.

So Oh, Wicked Wanda!…It’s interesting, because I don’t think I thought it was gonna be hard for people to get through that stuff. I thought they’d have issues with it, but I didn’t think it would be hard, or intense in that way. You could make the argument that the book was almost meant to feel like you just sat through a grueling four-hour war movie, or some atonal music piece, and now here’s The Benny Hill Show as a respite. [Laughs] But it’s clear no one’s really taken it that way. Which is good, I guess.

Collins: Perhaps for this audience, the atonal stuff is our Benny Hill Show. Then you get to the T&A romp, and it’s like, “Aaaah! It’s Metal Machine Music!”

Harkham: But what is it? Is it seeing swastikas on girls’ asses? Is that a problem?

Collins: No, and that’s the thing. You said you thought people would have issues with it; I didn’t have any issues with it, I just thought it wasn’t that funny. Which is sort of the least critical criticism that anyone can ever levy at anything…

Harkham: I feel like that’s important, though. I can’t remember who wrote it – maybe you wrote it – but there was a [Comics] Journal review about the black humor anthology [Black Eye, edited by Ryan Standfest].

Collins: Yep, that was me.

Harkham: I only read one review of that book, and that was in the Journal, and you said you didn’t find it very good because it just wasn’t that funny. Remember? [Laughs] That, to me, is a very valid criticism. That’s something, as a reader, I’m curious about: How funny is a funny anthology? That’s important to me.

Collins: Okay, I feel a little better then. [Laughs]

Harkham: I know that for my own work, the most important thing is that it’s entertaining. That’s number one. Any deeper or richer intention should be behind that. The main thrust should always be “Is this scene funny? Is it good? Is it scary? Is it strong?” I want momentum, I want this thing to be moving. Any other concerns, like personal expression, honesty, truthfulness, whatever it is – all the stuff you really wrestle with when you’re in art school – should be in play in the background.

So I think jokes are important. Oh, Wicked Wanda! is a little bit trickier. It sounds like you still engaged with it, you didn’t shut down, but you didn’t find the jokes funny. I do think there are a couple other ways of reading it that make it kind of interesting. People who don’t even want to read it can just look at it and still like it without reading it. The first year I was looking at that stuff, I never read it. I was just looking at it page by page and thinking “My God, these are incredible-looking pages.”

Collins: Well, it sits so well on that paper stock that you can look at it along with the other airbrush art in the anthology literally on a surface level. You can look at the surface of the page and enjoy it.

Harkham: And I think that’s important. I do.

Collins: You can also look at the Nazisploitation and S&M elements of the strip, and a few pages away you have CF’s strip, and you can get some resonance there. In fact, I feel as though the act of putting all the stuff that’s in here between two covers is almost like a game. I don’t mean that as a value judgment at all – or maybe I mean it as a positive one. The game is to try and puzzle out the context. “Okay, it’s a shorter, smaller volume; Sammy and Dan have said it’s the most focused one. So what is the focus? What am I not seeing?” Most of it I can make sense of, but the things that really stick out become a challenge. “What are they doing in here? What did he see?” That’s one of the pleasures of an anthology with a really strong editorial eye: trying to puzzle out the context the editor had in his mind when he put it together.

Harkham: Well, let’s see. Oh, Wicked Wanda! you had trouble with, and the Svenonius. [Long pause] Keeping in mind what we were talking about, about not wanting to smother readers with my goals or what I was trying to do…I definitely wanted to make something that got away from all the things that we take for granted when we think of anthologies, and when we think of comics, and when we think of comics within the context of the wider culture. When you pull it out of our little scene…One thing at play with Kramers 4 was that that book was, in some ways, a response to comics being embraced by the mainstream and by the wider book culture and art culture. 2003: Pantheon is releasing books, Fantagraphics and D&Q are now in bookstores, it’s becoming a regular thing, and comics are being presented more and more like literature in the way that they’re packaged, the way that the books are designed. [Kramers 4 was] my way of dealing with that, because I had no connection to that and didn’t grow up reading comics in that way. The Love and Rockets collections and the Jim Woodring collections were always 8 ½ x 11. They were just comics jammed together with covers in the back. [Laughs] They were just collections, really simple. Kramers 4, in some ways, was, “I want to get back to things being comics.” No context, no blurbs, just that energy of comics, throwing it all out there and leaving it to the reader to make sense of the work themselves.

When thinking about doing another issue of Kramers, I want to do something that’s gonna enter into that conversation of comics as literature and comics as fine art, but do it in a way that feels right where all those other books feel wrong to me. It’s a way of throwing out all the things we take as a given because that’s the way it’s done by Fanta and D&Q and First Second or whoever. You could make the argument that all previous Kramers have been about stripping context away, so let’s make one that’s all about context. So you think about having an essay to start the book. And you think about Takeshi Murata, who’s not a cartoonist, and I wouldn’t say those are comics in any form, but when you think of literary anthologies like Granta or McSweeney’s, often you’ll have somewhere in a book of prose a selection of sculptures or photography by a fine artist. Murata served that purpose. And you think about the size, and about trying to have meaty contributions and stories, and about a book you could buy at an airport bookstore and sit with for a couple days. That was really important to me.

One of the things that happens with the previous issues is that there’s a very off-handed way of giving the work: [in a singsongy voice] “Oh yeah, here’s Chris Ware, and here’s Martin Cendreda, and here’s CF…” I’m just tossing them out to the reader. With this, I wanted to present all this stuff with real respect and dignity. [Laughs] It gets a little bit tricky talking about this stuff, because I know that for everything I’m saying there’s a million arguments against it, and we could go into any one of these points and have a conversation. But I just wanted to make something that was really refined and clean and had a strong point of view. Someone mentioned that it’s an angry book, and I’m might agree with that. In a way I feel like I want to just throw everything out, and it’s a new start. [pause] Does that answer your question at all?

Collins: [Laughs] I think so! I don’t at all want to tease out of you some sort of revelation you’re not comfortable with because it proscribes reader reaction.

Harkham: I’m still figuring it out myself.

Collins: But the way you just described it makes me think that the fact that it’s a Kramers with a typewritten table of contents at the beginning is somehow the Rosetta stone of the entire project.

Harkham: Exactly. But dude, forget that. You don’t even need to go that far. Open the book, look at the endpapers: The endpapers are white. [Collins laughs] I’m serious! I am serious. Kramers has always covered every square inch of surface with content. It’s always been like “Just jam it in, as much stuff as possible, and if it’s not a good book, at least it’s a big book. [Laughs] One of these is bound to hit!” There’s a certain amount of insecurity when you’ve been working on an anthology for six months: “Fuck, I’ve got one month left. I’m gonna send out one last email to twenty people and be like ‘Who’s got something?’” With this, it was, “I’m gonna have a few people and I’m gonna give them space.” I told them all “I want your strip to start on the right-hand side, and I want it to be a certain number of pages, and I want it to be a certain kind of story.” I wanted to contextualize all this stuff, in a way that I never had before.

With my own work, with Crickets, it’s more like those old issues of Kramers. When it comes to how I present my own work, I like it to look like shit. I like it to look dashed off and simple and vulgar, so that when you read it, if there’s anything richer, it’s almost a surprise. I want to embrace all those exterior elements of a comic book so that it’s a little bit subversive in that way. Like, [Crickets #3’s lead story] “Blood of the Virgin” is called “Blood of the Virgin.” You know? And the cover of Crickets 3…I’m really proud of that issue, but there’s no signifiers when you hold that thing that it’s anything but a dirty, gross comic.

Collins: You went out of your way to trashify it.

Harkham: Exactly. [Laughs] I didn’t go out of my way to trashify it, but all my favorite writers, if there’s one thing in common, is that they write in a very direct way, with a certain clarity of thought, just saying things. I really respond to that. So Crickets 3 works for me [because] I wanted to make something that feels like a comic book, and all the things we think of as a comic book as comic readers. You get what I mean when I say that, because you’re engaging with the medium in that way. Crickets is very much a part of that conversation.

With Kramers 8, it doesn’t make sense to do that anymore. I’m 31, I’m not 23. It doesn’t make sense anymore to have everything be loud and crazy and messy. And anyway, everyone’s doing that for me. Everything kinda looks the way Kramers 4 looked.

Collins: BCGF looked like if Kramers 4 came to life.

Harkham: [Laughs] Well, that’s nice, I guess. I mean, I’m not gonna take credit for any of that sort of thing. But there’s a certain rough texture to everything, and that doesn’t really resonate for me anymore. If I look at the fine art I’m looking at, the books I’m reading, the fashion, the graphic design, all the things I’m interested in – it doesn’t look like that. So why do the comics I buy?

Let’s see if I can say this in a clear way so you don’t have to edit the hell out of it… [Pause] There are certain things, I don’t know what I should call them, but certain tropes of indie comics that are sort of a given. It’s a pretty incestuous community, the world of comics. I realized that if I stepped out of that a little bit and think of the wider context, there’s a way of approaching this book that feels really fresh, and yet feels like it’s connecting to the wider culture. Which I feel that comics have been doing anyway, for the last couple of years. Does that make sense?

Collins: Well, as we were just saying, it’s a Kramers with white endpapers, with a table of contents, with a prose introduction, with a cover that’s restrained even by the standards of #7. The package itself is making an argument.

Harkham: Yeah. It’s a difficult book for me to talk about because I feel like I’m still in it, even though I’ve been done with since September. I haven’t really been able to make sense of it. This is why I wanted to do this interview over the phone as opposed to me writing answers, because anything I would type, I don’t know how honest it would be. Over the phone, I can say I don’t have clear-cut answers or clear-cut reasons for making the book what it is, exactly.

But hopefully, with any piece of work, there’s multiple strands that are at play. Every time I would see your name come up in my email when we were communicating, I’d think of Game of Thrones, because I know you’re a big Martin fan. I’ve only just started that series, but he’s a good example of this. When you describe that book to someone, you can say, “It’s about this,” and it’s totally true, but you can also say “It’s also about this,” and that’s totally true as well. Not to say that Kramers is anywhere near a work like what George R.R. Martin’s doing [laughs], but you try to have multiple strands at play, multiple things that you’re working towards.

With this new issue, there is that one strand: “Okay, I want to make a book that actually looks like a book, that can sit on a bookshelf with good prose and good graphic design and good records. I want it to be part of the wider culture.” All these cartoonists are doing very, very unique work, and if there’s one connector – I don’t know if this is true, but maybe – all that work feels like it’s a little bit outside comics. Despite being totally informed by the medium, there’s something about it that looks or reads like it’s not so incestuous. They’re not responses to other comics. It feels like they’re engaging the wider culture.

So there was that element of wanting to make something that’s pushing past comics, because comics as a medium is already going there. You already have comics in every bookstore. You have mainstream coverage of cartoonists. So it’s like, okay, if we want to finally engage with that instead of avoiding it…I can avoid it with my own work, but it’s not fair to do that when representing other artists and putting together collections of other people’s work. That was an exciting challenge, to try to do that.

The next thing was, what’s the point of view? That’s where Svenonius and Oh, Wicked Wanda! obviously add a lot. Maybe they throw a wrench in things, but maybe that’s good. Obviously I don’t want anyone to dislike any of the pieces. That’s always a problem when doing an anthology. Every review of an anthology, as a given, will say, “It’s great, but like any anthology it has its problems.” [Collins laughs] There’s always those strips you don’t care about, because every editor has their own definition of what’s good.

Collins: But as a reviewer, for example, I realized a few volumes into Mome that the fact that I disliked a few strips in each issue is a big part of why I enjoyed reading the series. It helped me understand, “Okay, why does a comic work? Why does a comic not work? What are these two comics that are only a few pages away doing so differently?” I found that really helpful. So even when there’s stuff that you struggle with or dislike – I understand that as an editor, the intention is not to put in stuff and say “Oh, no one’s gonna like this – let’s see what they make of that!” But as a reader, it’s an experience that a regular book can’t reproduce. “Advantage” is a weird word for it, but it is a unique advantage of anthologies that they present different works that you may have very different reactions to, all between two covers.

Harkham: I think it’s the job of the editor to make the right decisions so that all that work creates a bigger whole. If you think of each creator’s comic as a chapter of a novel, and each person is bringing a different idea to the table, and each one is working well off the other, then a bad anthology is when all that gets muddled. They’re just running whatever, or they’re just running stuff they like, and there’s no clear tone or feeling, and it becomes a muddled mess. You engage with it not as a book but as a bunch of different strips that happen to be bound together.

Like you said, there’s a lot of anthologies, so to do Kramers isn’t so much because I’m like, “Oh I have to publish this guy because nobody’s gonna see it otherwise. It’s more about going, “I want to see a certain kind of comic book, and I want to push the reader hard, and I want to break past their barriers, the perimeters of what they expect, and give them something fun, something different.” That sort of thinking goes into play when you’re making your own book – it just so happens that you’re working with all these different bits and pieces from other people, and you’re trying to build this Voltron robot out of all these pieces. [Laughs] You can tell I’m still making sense of it myself.

Collins: You’re saying so many things that sound like you’re talking about a comic you drew from beginning to end. [Harkham laughs] To me, that says a lot about what Kramers is.

Harkham: If you’re a cartoonist and you’re editing an anthology, it’s very much an excuse to live in the skin of other people, for sure. That’s definitely at play. “Man, I love this girl’s work, she’s amazing, and I wanna be involved! I wanna present this stuff my way.” You want to get your fingerprints on it. So that’s definitely there. I think it’d be easier to have a free-for-all and say, “Okay, I have this many pages, I just need to fill it.” If I did that, I could probably get an issue of Kramers out every year.

It was a good learning experience on this one, because with only having to deal with about twelve people, I thought it would be a much easier process, but it wasn’t. It’s a huge undertaking. It feels like a lot of work. I never know why afterwards. When I’m in it, I should write myself a letter and give myself notes, so that next time I’m like “I want to do another Kramers,” I can read it and remind myself. I always forget, and it’s always the same issues that come up. “Ohhh, right.”

You’re always at the whim of your contributors. I think I never get over that, and I think I always resent that. As a cartoonist, after a while you start resenting that you’re spending so much time on other people’s work and not enough on your own work. You just become this maniac by the end, where you want it to be done, but at the same time you’re like “Fuck, I spent so much time on this, I want it to be good. I really don’t want it to be a waste of six months. Or a year!” It’s always a struggle. It’s a lot of work. I’m always surprised that it’s so much work, but it is. I’m sure that Eric Reynolds [editor of Mome] would say the same. It’s a pain in the butt.

Collins: I feel good that I went through all 40 pages of Oh, Wicked Wanda!, then. I owed it to you!

Harkham: Well, hopefully, even if you didn’t enjoy reading it, you got something out of it, or it enriched something else, at least in the context of the book. I felt like it was important to run that stuff. I don’t feel beholden enough to anything that I have to run anything. I’m a harsh editor in that way: “Do I need any of this?” I don’t feel beholden to anybody in any way. With the Oh, Wicked Wanda! stuff, the only real question mark was how people were gonna respond to it. But maybe that’s always the way, when doing anything. You never know. You just gotta go off what you want as a reader. That’s how I approach my own work, that’s how I approach Kramers: Finding out what do I feel like looking at and reading, and then trying to make that thing.

Images courtesy the artists and PictureBox