On the title page of Gilbert Hernandez and Darwyn Cooke's "The Twilight Children" #2, a forlorn Bundo holds up a picture of his family. He blames himself for his carelessness and lack of attention, and the rest of the village may also be treating the orbs in too sanguine a manner, setting Bundo up as a canary in the coal mine for the village. Cooke's clean linework has good facial expressions, and Bundo's grief primes the reader for the opening scene. The dialogue is excellent, especially the affectionate teasing between Bundo and his wife.

For those interested in hard science fiction, aliens or horror, "The Twilight Children" #2 won't provide it. The orbs increase in menace, but Hernandez's true focus is the small web of relationships. The story is cut from exactly the same cloth as his Palomar stories in "Love and Rockets." He keeps several subplots going at once, gracefully connecting all the characters into the larger framework of a small village setting.

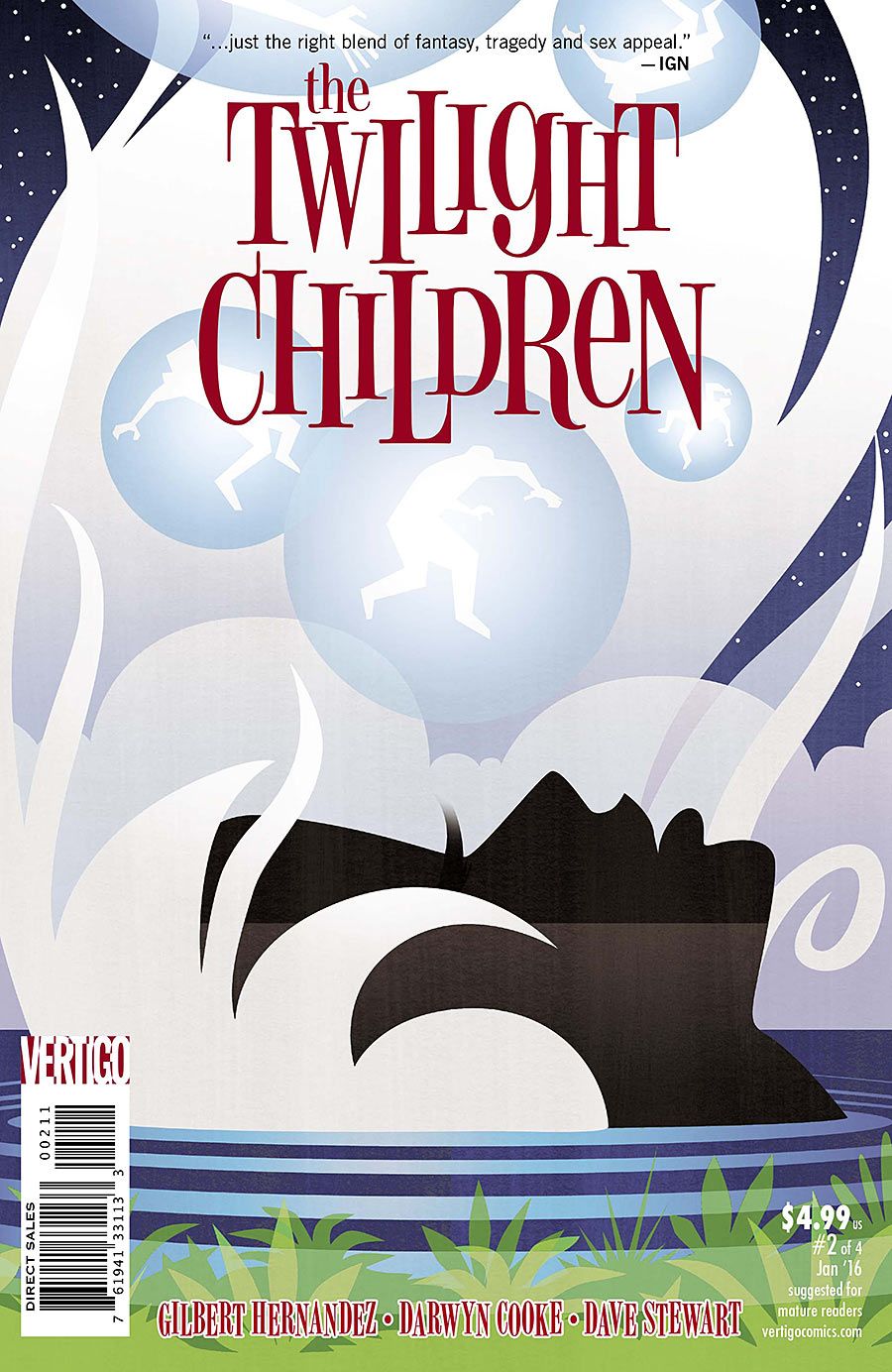

Cooke and Stewart's artwork is particularly elegant and eerie in a silent scene on the beach, when Bundo examines Ela's footsteps. Stewart's choice of a creamy, warm yellow for the orbs is unusual and thoughtful. In comics and other visual art, the supernatural is usually colored in cool tones in nighttime settings, since human fears are so closely connected to the cold and dark. In "The Twilight Children," the warmness and lightness of the sunlight hue reinforces the ambiguous status of the orbs. Are they dangerous or evil? Cooke makes another, similarly deliberate and effective choice by giving Ela's hair no black outline, setting her apart from all the other characters. Both her hair and the far-off, unfocused look in her eyes give her presence an unearthly air.

A lot happens in "The Twilight Children" #2, and all the different characters get panel time. The pacing is fast but doesn't feel rushed. Hernandez excels at showing normal, busy human lives. He brings just a touch of magical realism to add atmosphere, texture and suspense. The supernatural is never the main course, and the mechanisms of how and why are usually left open. I expect the orbs will continue to remain beyond the full reach of science. In their power and mystery, supernatural phenomena in Hernandez's stories draw attention to curious serendipities and unpredictable tragedies in life, providing a startling background for the simultaneous humility and grandeur of ordinary people.

Despite the multiple intersecting sources of conflict -- Tito's messy love life, the blinded children, Bundo's grief, Ela's presence and her strange effect on some of the men -- none of them build up a huge amount of tension. This, too, is characteristic of Hernandez's storytelling style. The last scene in "The Twilight Children" #2 shows Nikolas and Anton setting Felix the Scientist up, but the emotional turmoil of jealousy and the looming threat of serious violence is deliberately muffled and diverted by chance occurrence.

Since so much of the storytelling occurs through Hernandez's dialogue and through Cooke's well-composed panels, the most apt comparisons come from theater. The material of "The Twilight Children" is the same as that of Modernist playwrights like Eugene O'Neill or Edward Albee's preoccupations -- betrayals, trauma, childhood, loss -- but, unlike those playwrights, Hernandez seldom allows these sources of anguish to soar into showy, cathartic truth-telling soliloquies. His style and treatment of his subjects is more like Thornton Wilder's approach: seemingly simpler and cooler, less raw, more meandering and earnest, with more optimistic conclusions and tidy mysticism.