At the beginning of I Am Batman #0 (by John Ridley, Travel Foreman, Norm Rapmund, Rex Lokus, and Dave Lanphear) Katana offers Jace Fox the chance to become her apprentice. He tells her no, saying “Katana fights some pretty bad people, but I want to fight a system.” It’s a powerful statement. In an age where everyone from Nightwing to Superman is re-examining the way they fight injustice, it’s one of the boldest statements of intent that any hero has made. Unfortunately, New York's Batman is blind to a huge piece of the system he’s trying to fight. Batman has always had a fraught relationship with the police. However, his stories have rarely scrutinized the role of law enforcement in anything other than a cursory manner.

With the introduction of a new, young, black Batman in the cultural climate of 2020, fans expected that to change. Within a few pages of Jace’s fearless statement of intent, however, any hopes are dashed. The next page shows police in full riot gear, facing down an angry protest. The cops are discussing deescalation, pulling back to calm the situation. Before the calm, rational officer can convince his superior of the plan, an unprovoked protestor throws a rock, leaving the cops no choice but to attack with their batons.

In case the book's point of view wasn't clear enough, the following issue has an exchange where two officers commiserate that “no one respects the police anymore”. I Am Batman is full of scenes like this. Rather than looking at systemic problems of policing, the series often shows good cops trying to avoid conflict and uphold moral standards, while a few bad, corrupt cops ruin everything, giving everyone a bad name. This attitude comes to a head in I Am Batman #12 (by John Ridley, Christian Duce, Rex Lokus, and Troy Peteri).

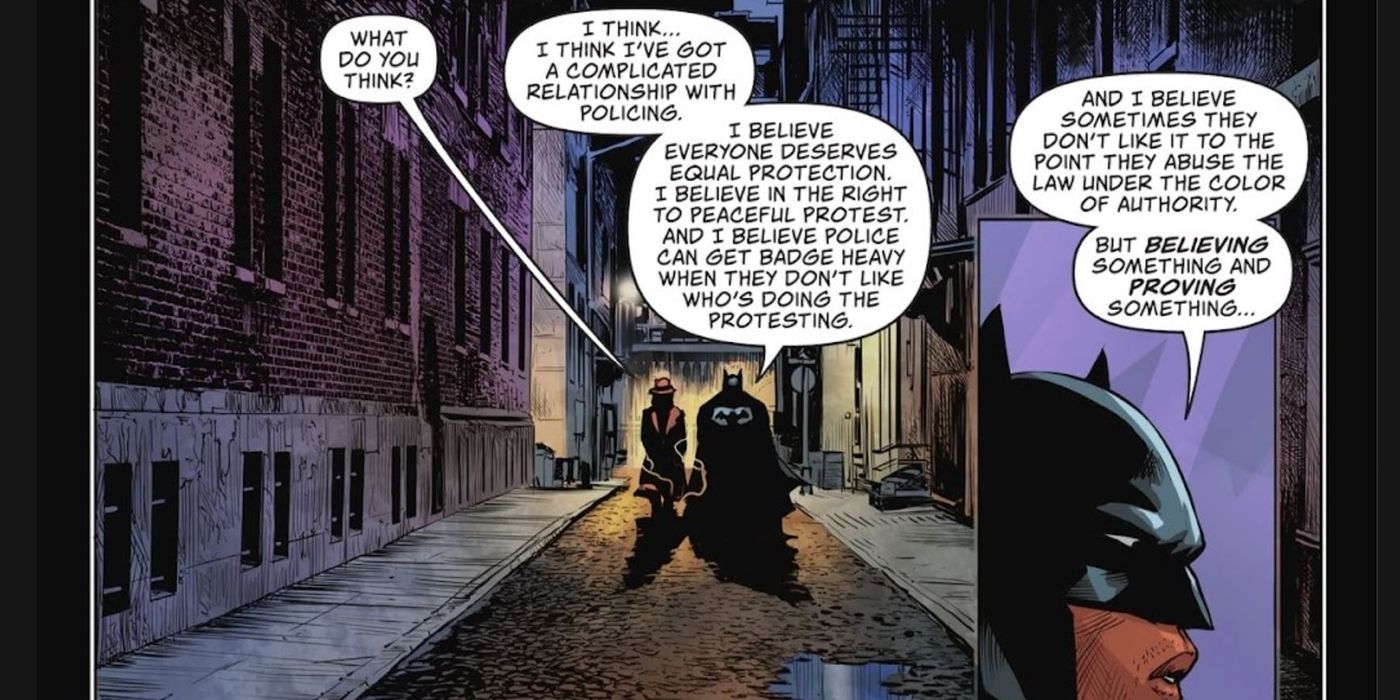

Jace is asked directly about his opinion of the police and he responds “I believe everyone deserves equal protection. I believe in the right to peaceful protest. And I believe police can get badge heavy when they don’t like who’s doing the protesting”. While this speech is phrased in vague enough terms to leave it open to interpretation, it’s hard not to read it as repeating the same “a few bad apples” rhetoric. This reading is especially unavoidable as it comes directly after one of these 'bad apples' is implicated in Jace and The Question's murder investigation.

I Am Batman is not completely unaware of its cultural moment. Elsewhere, the series make attempts at reckoning with white privilege, wealth inequality, and the rise of conspiracy thinking. During the Fear State event, I Am Batman depicted the victims of Seer's manipulation with understanding and compassion, showing a willingness to engage with the very real fear that lies beneath the impulse to turn to conspiracy theory.

Unfortunately, this willingness to engage does not seem to extend any further. Rather than applying this insight to their many cop characters, distrust or criticism of the police is lumped in with other conspiracy beliefs. Of course, this is a fictional story, and the writers are not obliged to engage with real-world issues. However, they seem determined to do so. The protest in Issue #0 shows the crowd wearing medical face masks. Issue #4 (by John Ridley, Stephen Segovia, Christian Duce, Rex Lokus, and Troy Peteri) references the very real history of The Tuskegee Experiments and COINTELPRO.

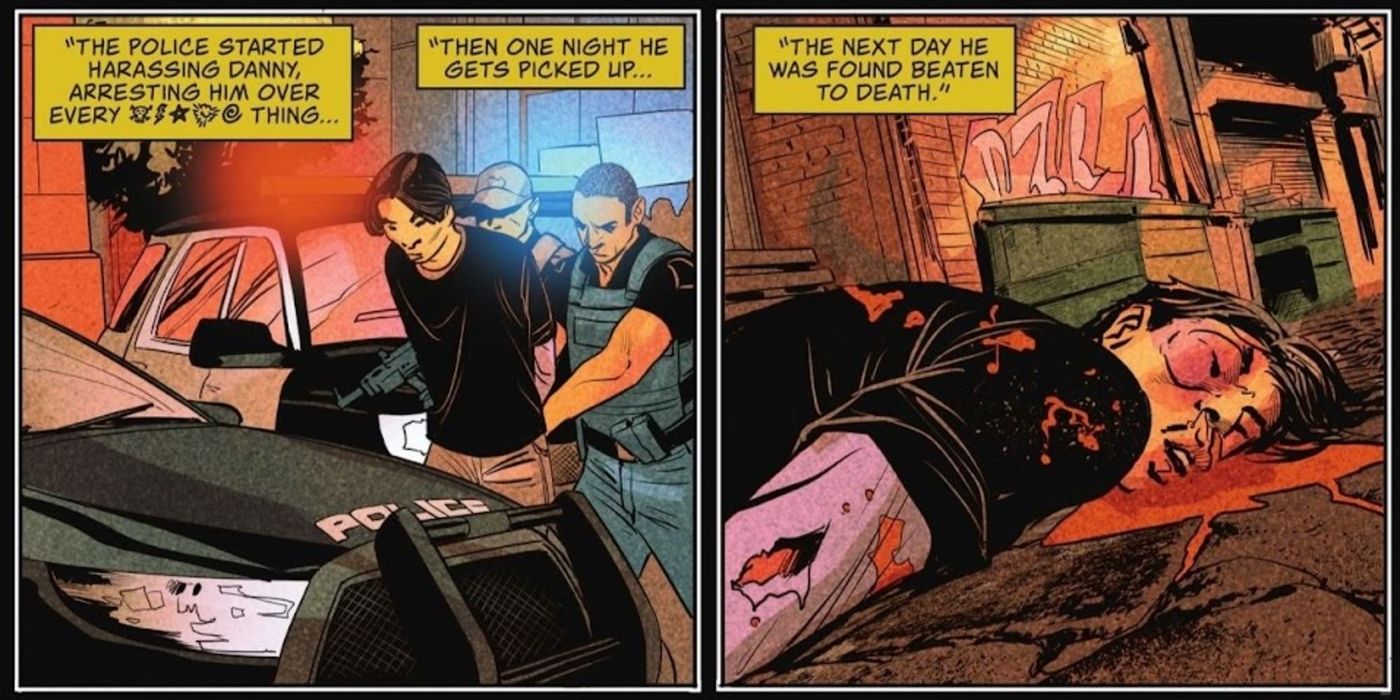

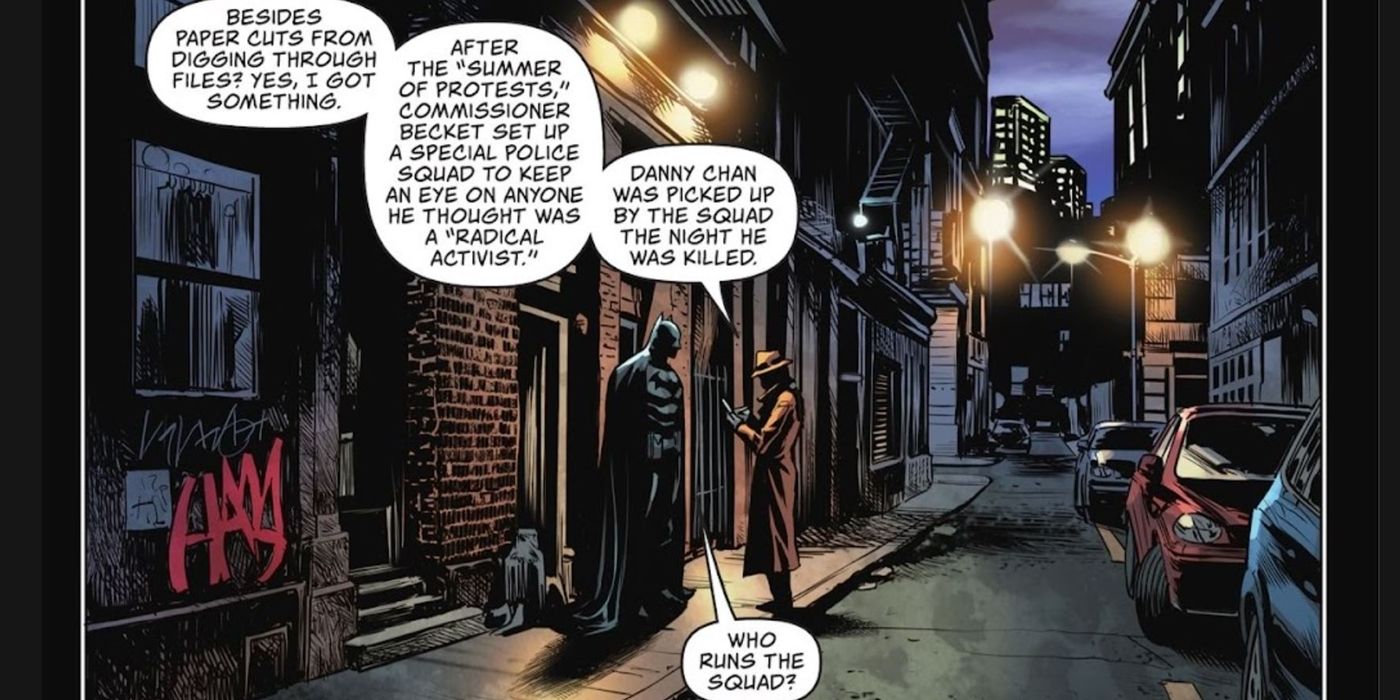

Issue #12 calls back to a “summer of protests”, a clear reference to the real-world Black Lives Matter Movement. This last reference is particularly jarring. Key to that movement’s message is that the problems with policing are definitively not the result of a couple of bad cops but caused by long-present systemic issues in the way cops are trained, deployed, funded, and treated under the law. I Am Batman deliberately draws parallels between its story and these real-world events, inviting readers to apply its lessons to their world.

One newly introduced storyline does have the potential to address these issues. Renée Montoya's appearance in New York and her decision on whether to take over as police commissioner could explore some structural problems with the force. Throughout recent issues she is debating whether her presence can right the wrongs of the previous administration. Her efforts would be the perfect place to explore the extent to which one person can actually change an organization like the police, for good or ill.

Renée tells a fellow officer that she is checking to see if the previous commissioners' bigoted personal views seeped into the department's work. Such an investigation could show that, yes, the bias of the commissioner resulted in many wrongful arrests. Better yet, it could show that the commissioner didn't need to inject his personal prejudice into the police force, because it was already there, written into the laws they uphold and the culture they are a part of. Unfortunately, no such inquiry takes place. She was lying to the officer in order to get access to the records for The Question's investigation. The lack of current focus on these problems is summed up perfectly by Batman himself.

When visiting a non-violent activist organization with some very real grievances, he shuts down any discussion of his role in the proceedings. The activist tells him that he's part of the problem, that he's an "agent of oppression", alongside the police. "Save the speech. We're looking for answers", The Dark Knight barks back. No matter how much Jace insists he's fighting "for the people", no matter how much sympathetic backstory his villains are given until he truly engages with the reality of policing, the activist will be correct. New York's Batman will not be fighting systems of oppression, he will be an agent of them.