At first glance, The Multiversity: Guidebook #1 — this month's chapter of Grant Morrison's grand epic exploring DC Comics' Multiverse — looks like a somewhat-skippable book, supplemental material of the sort that the publisher used to release under the title Secret Files & Origins.

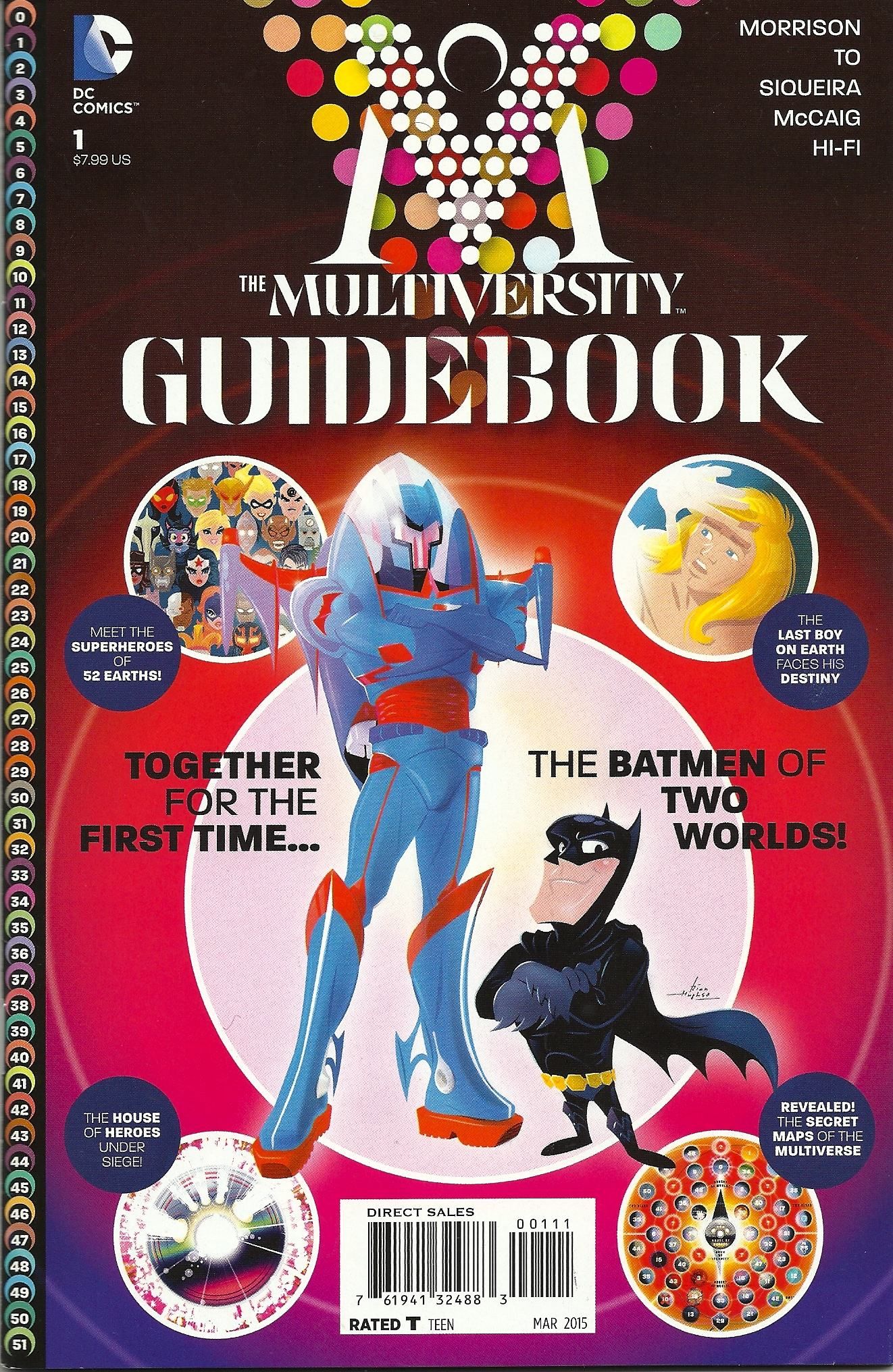

Everything seems to bear that out, from the content advertised on the cover (like the already well-traveled map of the Multiverse) to the artists involved (Marcus To and Paulo Siqueira are good, but not of the same superstar status as previous Multiversity artists) to the particular Earths the cover boys come from (the Batman on the left is from Morrison's new version of the world of The Atomic Knights; the Batman on the right is an off-model drawing of the character from an Earth introduced in Morrison's brief Action Comics run).

Second and third glances confirm that initial assessment of this book's importance. On flip-through, you'll note that about half of its 70 pages are devoted to illustrated prose in an airy, space-filling format, defining each of the 52 Earths and identifying a few of the key players.

But once you start reading the thing? Well, on a purely conceptual level, as a piece of comics writing and a piece of comics writing about comics, it's probably the most ambitious, important and fascinating chapter of The Multiversity to date. And that's in addition to being an extremely timely reminder of how to "read" DC's continuity-realigning storyines and just what, exactly, it is that makes DC Comics and the DC Universe so special in the first place.

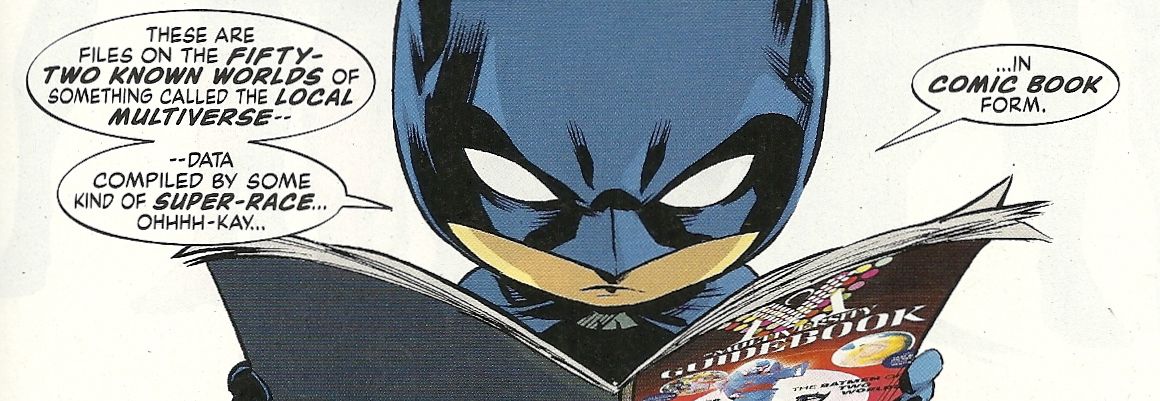

And, this being part of The Multiversity, a storyline in which comic books themselves play such a pivotal role within the story – serving as gateways for various forms of information from different realities, with Morrison and company riffing on the idea that the fiction of one reality is the reality of its own setting — that map and those profiles of the 52 Earths are central. They are the story, fuel for the plot of the issue and the overarching narrative. Sometimes The Multiversity is so meta one wonders if it shouldn't have been called The Meta-versity. (No, it shouldn't have; that's a stupid name.)

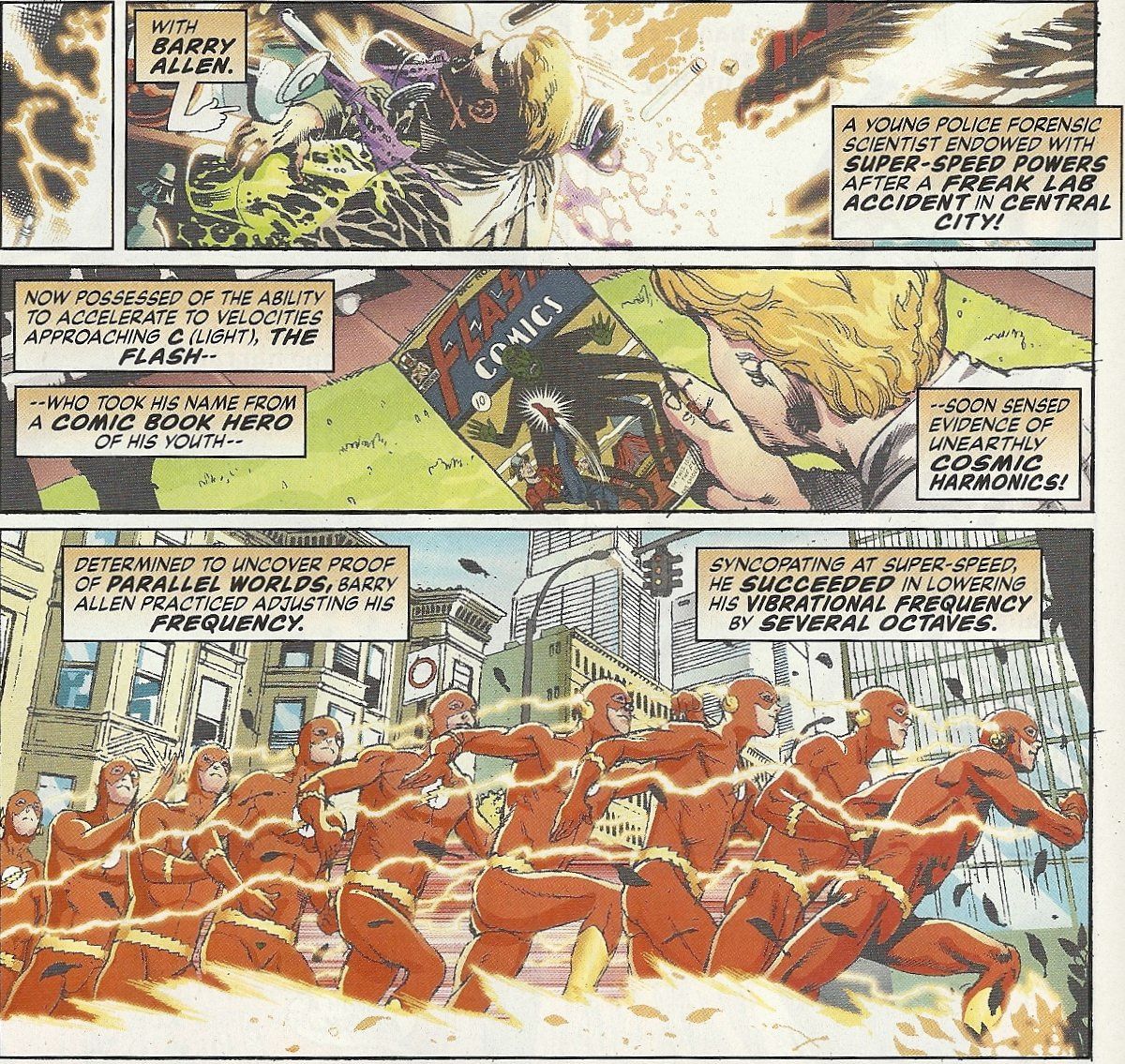

If you've been reading The Multiversity, then you know it's a continuation of subplots Morrison has been working on for years, alone and in conjunction with other DC writers, and themes he's been working on for his entire comics career (albeit mostly in his DC Universe work). And, as he makes clear in this issue, it's what DC writers and artists at least as far back as Robert Kanigher, John Broome and Carmine Infantino were doing in 1956, and which Gardner Fox and Julius Schwartz started doing in 1961.

Nix Uoaton, last of the race of Monitors (e.g. the Monitor of Crisis on Infinite Earths), was living a life of semi-amnesia on a world much like our own. When the Multiverse came under attack by mysterious entities called The Gentry, he transformed into "Superjudge" and attempted to save it, falling prey The Gentry and becoming one of their corrupted agents. A small band of heroes from various worlds have gathered in The House of Heroes, a makeshift HQ between time and scape. After the setup in The Multiversity #1, each of the successive issues — four previous to this one — have been set on a different Earth, its heroes dealing with its villains, and various iterations of The Gentry, invasion from other realities and the effects of haunted, weaponized or otherwise dangerous comic books.

The Guidebook's guidebook portions are embedded within a story by Morrison and drawn by Marcus To and Paulo Siqueira and colored by Fave McCaig and Hi-Fi.

"Maps and Legends," as the story is called, begins on Earth-42, home of the Little League that Morrison introduced in Action Comics. The Legion of Sivanas, alternate versions of Dr. Sivana from 25 different Earths united together and introduced in The Multiversity: Thunderworld Adventures, have invaded, seeking "The Maps of The Multiverse." This little Batman is in grave danger until the arrival of a bigger, better-armed and infinitely more violent Batman from Earth-17, home of Morrison's Captain Adam Strange and his Atomic Knights of Justice.

The little Batman picks up one of the comics strewn about the battleground and starts reading about Earth-51, where Kamandi, a new version of OMAC and versions of the New Gods interact (an Earth of several Jack Kirby creations, then). While Kamandi and his allies investigate the broken and empty tomb of Darkseid, Kamandi finds hieroglyphics on the wall, a comic book-like story, and begins reading. That's another comic book sequence, essentially detailing the entire history of DC's Multiverse concept in just four pages.

This begins with the first appearance of Barry Allen who, remember, originally got his name "The Flash" from Golden Age Flash Jay Garrick, whose comic book adventures Allen read; this first story of the Silver Age then, by Kanigher, Broome and Infantino, is where Morrison finds the idea of comic books as other realities. A few years later, after all, Allen would journey into the world of Garrick's Flash comics in the first story of vibrating Multiverse, "Flash of Two Worlds" by Fox and Infantino.

From there, we get the Infinite Multiverse, the Crisis on Infinite Earths that reduced the Multiverse to a single "unstable, uncertain, post-traumatic" universe, the changes to DC's time-ine that occurred in Zero Hour and Infinite Crisis and, finally, 52, which caused the Multiverse to "erupt" from the single universe, to the events of Flashpoint, which of course led to the current DC Universe as we know of it, the New 52 line of comic books. ("The Flash -- always there at the electric heart of every momentous occasion," as the comic within the comic within the comic within the comic puts it.)

All of these changes, the story makes clear, happened and mattered, even if no one within the stories themselves remembers them. "Only The Monitors kept a record of it all," the narration says, "written into the fictions of Earth-33."

Earth-33 is, if you consult your guidebook, Earth-Prime; our world, the real world ... or at least, the real world as we can read about it in these comic books. It's a nice reminder, one that might have been even more welcome closer to the reboot of The New 52, that the events of those comics are real to us, no matter what changes editors and writers might make to the characters, which memories and events are altered or excised. Those changes are all part of the story.

More elegant still may be the Map itself, which is nothing less than Morrison literally mapping the cosmology of the DC Multiverse so that every single DC Comic story ever written has a place in the same shared setting ... even if the events of Neil Gaiman's The Sandman, or Jack Kirby's Fourth World comics, or Sugar and Spike or Batman Beyond or those "Earth-One" original graphic novels are separated by vast walls of time and space. It's really quite something to read, particularly because while Morrison may be serving as cosmic cartographer, his Map is really just a distillation and organizational system to hold the stories of literally hundreds of men and women over some 75 years now.

As for the profiles of the Earths, illustrated by a variety of artists (some of whom are matched to the characters because of their work on them previously), it's noteworthy that Morrison defines an impressive 45 of them, leaving seven of them with question marks, and identical notes saying that these mystery worlds are each one of "7 UNKNOWN WORLDS ... created by an Inner Chamber of 7 Monitor Magi for a mysterious purpose."

We've seen many of these worlds and their residents show up in The Multiversity and/or Morrison's New 52 Action Comics run, and it's interesting to see which worlds make the cut and which don't ... as well as to track the way in which those worlds have been changed.

For example, many of them are the worlds of Elseworlds specials and miniseries — the Just Imagine Stan Lee... suite of books, the Tangent line, Darwyn Cooke's The New Frontier, Mark Waid, Alex Ross and company's Kingdom Come, Howard Chaykin and Dan Brereton's Thrillkiller, Doug Moenc, Kelley Jones and company's Vampire Batman comics, and so on. They've been slightly rejiggered, though, so that the Western world of Chuck Dixon and J.H. Williams III's 1997 Justice Riders has new additions of various Western heroes, and the pirate Baman of Dixon and Enrique Alcatena's 1997 Detective Comics Annual #7 is now set not in old-timey days, but a post-diluvial future.

This may all seem like a stop-gap of a comic, something to kill time while Jim Lee finishes drawing the next official chapter of Mutliversity, but it ends up being maybe the most DC comic book of all time.

For here Morrison takes what is often cited as a negative about DC's line of comics — including by plenty of people who make, edit, publish and promote those comics — and reframes it as their strongest, most endearing virtue. It's a bit of a love letter, but it's more an alchemical formula, turning leaden comics-making into gold. The secret? Reminding readers that it was never really lead at all, but was golden all along.