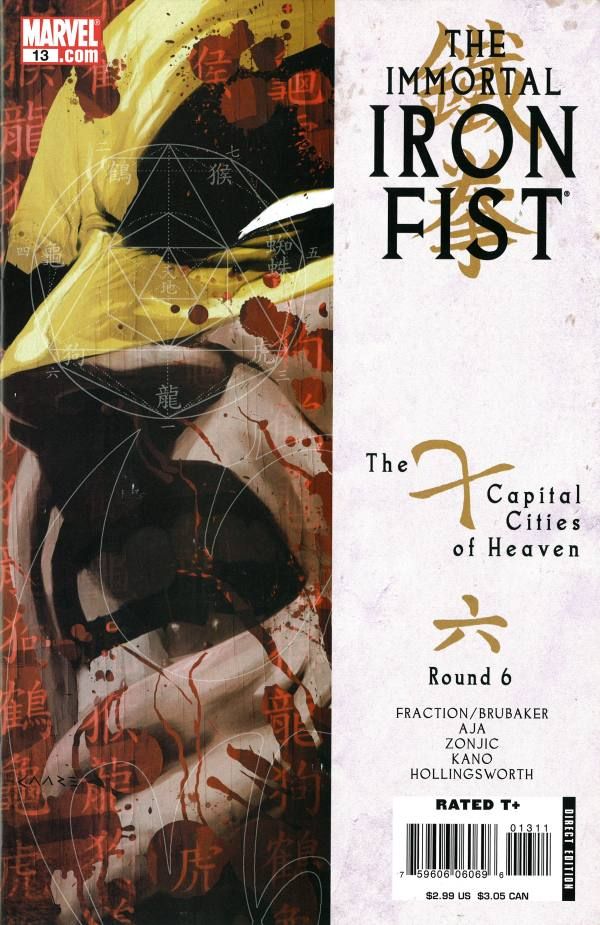

"The Immortal Iron Fist" has been, by far, the best Marvel comic of the past year. Unfortunately the penultimate chapter of “The Seven Capital Cities of Heaven” is tarnished by inconsistent, inferior artwork.

The writing is five-star, as writers Matt Fraction and Ed Brubaker weave complex narrative threads, a vast array of characters, and various timelines into a thrilling tapestry of loyalty and betrayal. You might not expect an Iron Fist comic to be one of the most formally complicated series on the shelf, but it certainly is. In the past timeline, Danny Rand’s father struggles for his dignity, while in the present Rand’s compatriots are forced to build an interdimensional train as Iron Fist plans a revolt in the mystical city of K’un-Lun. All of this is set within the larger structure of a martial arts tournament, and the still larger structure of the Iron Fist legacy. Yet Fraction and Brubaker don’t overwhelm the reader with too much information. The pacing is perfect, building to what will surely be a magnificent climax in the next issue.

But the distinct, moody shadows of artist David Aja have been replaced, for the bulk of this issue, by the thin, awkwardly positioned linework of Tonci Zonjic. "The Immortal Iron Fist" has used rotating artists throughout its run, but strategically so. Usually, Aja illustrates the main, Iron Fist-related sequences, while other artists tackle the flashbacks. In issue #13, Aja is barely present, providing only three pages of art. His three pages only help to reveal how inferior Zonjic’s attempts truly are. Artist Kano provides the flashback artwork here, and his work is excellent, but most of this issue�"this important issue, leading into the finale�"is marred by stiff Zonjic compositions and overly simplistic rendering.

The Zonjic pages are passable when he’s drawing Danny Rand’s friends, working on the train project, but as soon as Zonjic illustrates any of the K’un-Lun sequences, his work reveals its flaws. Take pages 13 and 14, for example, in which the mysterious Prince of Orphans proposes revolt to the assembled competitors. Fat Cobra looks like a comical cartoon sidekick while the other characters look like refuges from a costume party. In the hands of David Aja, these characters were strange and wonderful and dignified. Here, Zonjic turns them into “Kid’s WB” versions of themselves, and the shift is jarring.

I know the realities of comic book production require fill-in artists, and I know Aja was unable to produce pages because of personal matters (his wife recently had a baby, apparently), but when this story arc is collected in a fancy hardcover, this particular chapter will remain as a blemish on an otherwise exemplary story.