In the afterword to his new graphic novel The Harlem Hellfighters, writer Max Brooks cites two of the most common objections he encountered while shopping his screenplay about a regiment of black soldiers who fought for the United States in World War I: First, most Americans weren't terribly interested in the first World War, a subject they knew almost nothing about; and, second, most Americans weren't terribly interested in stories about African-American soldiers fighting in that war they weren't interested in.

It likely won't surprise anyone who reads The Harlem Hellfighters that it began as a film script — for a made-for-TV movie for TNT, actually, although the cable channel ultimately passed — as the cliches from virtually any war movie ever made are present, but that afterword does include an impressive example of why Brooks felt so passionate about the project. He recounts a discussion with an African-American professor who argued that one of the ways those in power have oppressed black people is by wiping them out of history books. When Brooks mentioned the Hellfighters, the professor responded that there were no black men fighting in World War I.

This, then, was history obscure even by the standards of academics who care passionately about the subject.

So, the graphic novel has a mission beyond providing an entertaining war story (and finally drawing Hollywood interest in that film Brooks originally conceived); it endeavors to restore a small but crucial bit of American history, to remember a forgotten (likely forcibly so) chapter in the centuries-long struggle for racial equality in the United States.

Given Brooks' pop-culture cache as the bestselling author of World War Z, the book has garnered a great deal of media attention, and that alone is a sort of fulfillment of its mission: I heard Brooks and a former commander of the Hellfighters' regiment interviewed about the Harlem Hellfighters on NPR while driving to work one day; a quick search reveals the project has been spotlighted in such mainstream outlets as Newsweek, Time, The Christian Science Monitor, Entertainment Weekly, USA Today and Slate.

But it's nevertheless disappointing, if not frustrating, that the comic isn't a better one.

Yes, the combination of the historical hook and Brooks' reputation has gotten people talking about the real Hellfighters, but it's really too bad the book is merely serviceable rather than great, something more notable for its existence than for what it accomplishes in its pages.

The story is that of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an all-black fighting force segregated from white soldiers. They called themselves the Black Rattlers and were nicknamed by their French allies as "The Men of Bronze"; "Hellfighters" is the name their German enemies gave them, for their fierce reputation of never losing a man to capture and never being pushed back.

Brooks introduces readers early on to the usual motley assortment of men from disparate places, backgrounds and beliefs who will naturally come together by the end as brothers, their friendships forged in battle. While some ancillary characters are real people, and some with larger roles composites of others, the ensemble cast consists mostly of character types.

We follow them as they train, as they journey to Europe, as they rankle under performing hard labor rather than fighting, as they finally get the chance to enter combat and learn just how horrible war (especially that war) is, as they face all sorts of adversity and as they emerge as heroes.

What differentiates this from your average war movie, and makes it something more than a WWI version of Glory, is the contrast between the way the fighters are treated on the battlefield and on the streets of France versus the way they're regarded back home: A third-act complication involves the U.S. military intervening to instruct French forces on how African-American soldiers are to be treated, so that they don't return to the United States with new ideas about equality, or with the aura of heroes.

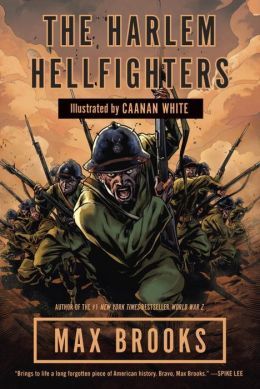

Caanan White, who's given rather short shrift on the cover, is a fairly strong artist, but his style is rather unremarkable. His figures and faces look as if they've been culled from your average modern superhero comic, and it can be difficult to distinguish the various races and nationalities of the characters, which is obviously a bit problematic.

Or is it? The book is in black and white, but a very stark black and white; it is literally black and white, with no gray. The choice certainly visually argues that everyone is the same, regardless of the color of their skin (they're all paper white, with ink-black features) or their country of origin, and nothing distinguishes the black American soldier from a white American soldier from a French soldier from a German one — nothing save their uniforms and context clues.

I don't know if the coloring was a storytelling choice or an economic one — much of the book looks rather cheap, from the generic lettering to the recycling of the splash page for the cover — but given the importance of color in the story, and the fact that the story and art are somewhat generic, color, or at least shaded art, probably would have helped give The Harlem Hellfighters a chance to better distinguish itself visually.

Brooks' aforementioned afterword does a fine job of explaining what he felt was important about the project, and offers a lot of behind-the-scenes information (were I him, I wouldn't be so eager to suggest that I really wanted to do a movie, but had to settle for a comic instead). More importantly, it walks us through the history a bit, and offers a healthy biography and suggestions for where to learn more about the real men and the real history that led to this graphic novel.

Harlem Hellfighters accomplishes its mission, then; it's just too bad it couldn't have done so more gloriously.