In the days since Tokyopop announced it would stop publishing manga, a few pundits have responded what struck me as a disturbing note of glee, a sort of satisfaction that that manga thing is finally over with. Doug Wolk has a piece at Time Magazine with the headline Manga Revolution Apparently Over: Tokyopop to Shut Down. And here's Tim Hodler at The Comics Journal:

Tokyopop is closing down its manga line. Not long ago, this company and others like it were sometimes pointed to as the future of comics publishing. I suppose they still might be.

I'm a little mystified by that last bit. Is he saying that the future of comics publishing is that everyone will go out of business? Well, everyone dies. But Tim and Doug seem to have missed an important point, which is that Tokyopop (and the other manga publishers) did in fact change comics publishing; Tokyopop may be no more, but ten years ago, it was the future. Graphic novel sales quadrupled between 2001 and 2007, and at the ICv2 graphic novel conference in February 2007, ICv2 editor in chief Milton Greipp singled out manga as the reason for that increase:

I think the biggest factor was Tokyopop’s expansion of their authentic manga line and bringing in original material for girls. Suddenly there was huge growth in a business that was usually flat, and it opened up new opportunities for other categories as well.

The emphasis is mine. That was at the peak of the manga boom, and sales have declined since then, but that surge of new readers has changed comics in many ways, all of them for the better.

Ten years ago, "comics" meant superheroes, newspaper strips, and a handful of artsy graphic novels. Comics were a niche medium, and they were hard to find outside comics stores. Manga brought about two structural changes that have affected the market in a lasting way. One is bringing girls and women to comics en masse—there have always been women who read comics, don't get me wrong, but in the 1990s the vast majority of comics were made by and marketed to men. No one was wooing girls and women as a distinct market, or setting out to publish comics that would appeal to them. Say what you like about Stu Levy (and I have!), he knows what girls like.

The second factor was bringing comics into bookstores, where casual readers could find them. Would that have happened anyway? Maybe, but probably not. Bookstores only give shelf space to books that sell, and manga sold by the boatload (some of it still does). Superhero trades don't look good in bookstores, where they are usually shelved spine-out; art-comix are expensive and have a small readership. But manga? Just a few years ago, my daughter's idea of a grand Saturday night was going to Barnes & Noble with her friends, buying five or six volumes of InuYasha, then staying up all night reading them. And she was not unusual; individual manga volumes often made the USA Today bestseller list, holding their own against Tuesdays with Morrie and Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. Furthermore, manga are like Harlequin romances—if you buy one, you will probably buy more. Bookstores started carrying them in bulk because the numbers were there.

There's more. Librarians quickly realized that manga brought in the teens (both boys and girls), and they became avid supporters of graphic novels as a medium. This in turn led to more acceptance by educators and parents. Again, without the manga phenomenon, this might not have happened; graphic novels would still be shelved in the art section and only a handful of people would know they were there.

By bringing comics to young people, manga opened up more possibilities for publishers. Sometimes it's hard to imagine something until you actually see it, but once publishers saw teens and tweens lining up for graphic novels, marketing to that demographic became an easier sell. Would First Second Books exist in a world without manga? Would Kazu Kibuishi's Amulet and Raina Telegemeier's Smile be the successes they are? Again, maybe, but I think the Manga Revolution helped grease the skids. Stylistically, those graphic novels owe no obvious debt to manga, but manga helped build the market for them, got kids reading comics and got teachers, librarians, and parents on board with the medium.

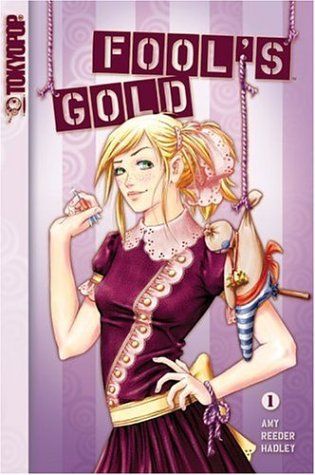

Finally, take a look at the young creators that Tokyopop signed to their global manga program and you will see the face of comics today. Amy Reeder (Madame Xanadu, Batwoman), Svetlana Chmakova (Nightschool), Queenie Chan (Odd Thomas), Amy Mebberson (The Muppets, Strawberry Shortcake)—all got their start with Tokyopop and went on from there. More are waiting in the wings. Pick up the Fraggle Rock anthology or one of the Pixar comics produced by BOOM! Studios; both are chock full of fine work by Tokyopop alums. And that's not to mention creators like Faith Erin Hicks who don't make global manga but were first drawn to comics by manga.

It's not just that those creators started reading comics because of manga, it's that they started making comics as well. The superhero comics establishment isn't particularly welcoming to new creators, but Tokyopop encouraged them through its Rising Stars of Manga program. There were flaws in the program, no doubt, but they got a lot of young artists and writers to think seriously about making comics at a professional level. It helps that manga is a medium that fans talk back to—it's part of the culture to make comics and write stories about the characters. That gets readers into a deeper level of involvement with the medium and encourages them to create original comics.

Some of these changes might have happened anyway. There were certainly worthwhile, female-friendly comics being made in the 1990s, but there was no mass market for them. There have always been aspiring comics artists, but they didn't have places that would accept their work or much of a community in which to discuss it. Webcomics, DeviantArt, the internet in general, all have opened up the comics world to new readers and creators alike, but manga gave the comics market an organizing principle for a while. It encouraged bookstores to stock graphic novels, young people (and adults) to read them, and artists to create them.

Here's the thing about revolutions: They change the world, but they seldom achieve the revolutionaries' original vision. Who knows what Stu Levy had in mind when he coined the phrase "manga revolution"; most likely, he was just being facetious. But manga did transform the comics world. It took comics out of the hands of fanboys, collectors, and hipsters and made them a truly mass medium.

No one, not even Stu Levy, expected that we would all throw over our American comics for Japanese ones. Japanese manga were significant in their own right, sure, but they were also a catalyst, bringing a new way of reading, creating, and marketing comics to the U.S. If every publisher dropped manga tomorrow (not likely, by the way—there are plenty of manga that continue to sell well, and niche markets are better served than ever), the comics landscape would still be forever changed—for the better. Viva la revolution!