And Fun Home isn't, like, unimpugnably perfect. The first chapter flat-out blew, and the art wasn't, by itself, anything to write home to mama about.

And, hell, to it's credit, American Born Chinese was certainly unique. I'd never seen anything like it. COMICS have never seen anything like it. In terms of sheer balls out bravuara, this was absolutely the comic of the year.

T'catch you all up.

It's a multi-tiered narrative about racial identity and what it means to be American filtered through Japanese Chinese legends and TV sitcoms and, heck, even straightforward drama.

When I was responding to Burgas' Fun Home not-review (as opposed to his Fun Home review, which was good) I called ABC a kid's book. But what I failed t'communicate was that I didn't mean this as a slam; quite the reverse. I've always figured that writin' kid's books is harder than writing for adults. Obviously, there's content you can include in an adult book that you can't in a kid's book and ya can't get TOO labyrinthine with plot structures or too bogged down in background detail or you lose your audience and they go off to watch the modern equivalent of "Saved By the Bell." This isn't so much a problem if you're penning The Babysitters Club goes to Disneyland, but if you're trying to deal with serious issues, as Yang deals with the themes of personal identity within mass culture, it's tougher to tailor your material to a teenage audience. And on top of that it's also more important for young's to hear these kinds of issues discussed, especially since teenager hood is when most of us are first forced to confront our own identity issues and really decide Who we're gonna be. And it's necessary for grown-ups with a little bit of wisdom under their belt to share their point of view with the kids who're dealing' with this stuff.

So we've got the tricky problem of dealing with these thorny issues in a kid's book for one. But this is a kid's comic, and a kid's comic about personally integrating your ethnic culture and mass culture? Damn near unheard of.

So in terms of innovation American Born Chinese is a better book'n Fun Home.

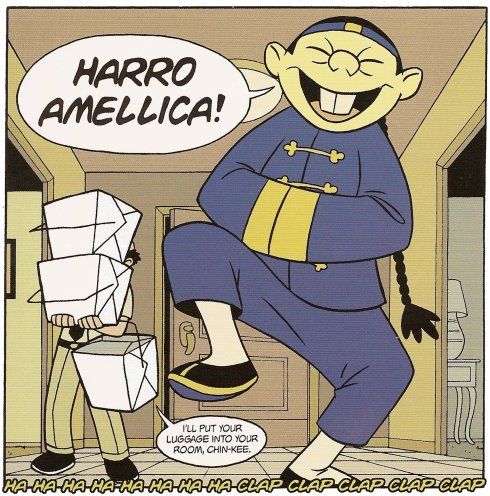

That said, let's break it on down by specifics. What we have here, for the first 200 pages, is three thematically connected short stories. First, there's the TEEN DRAMA, where American Born Chinese student Jin Want deals with the attendant problems of being in high school and, due to being one of only two Asian looking' kids in his class OBVIOUSLY DIFFERENT. Thorn there's the MYTH, based on the actual Japanese Chinese Legend of the Monkey King, where our simian protagonist attempts to gather enough personal power to force the other Gods to accept him. Then there's the comedy, or maybe "comedy" where white High School kid Danny has to try to fit in while bein' shadowed by his VERY stereotypically Asian cousin, Chin-kee.

And this structure works well. The three stories are, respectively; drama (mostly), quest adventure (mostly) and black comedy (mostly) rotate, and when any one narrative shows of getting stale, BAM! instant tonal shift. Yang's instinct for deducing when one branch of the story tree has juuuuuusssst started to wear out is damn near uncanny, and this keeps the book lively and compulsively readable.

He's also got a keen eye for absurdist detail; Notice the laugh track in the panel above. That's a GREAT trick, and deserving of an essay on its own. Or my absolute favorite panel of the book has the Monkey King is laying down some righteous vengeance. The Gods booted him out of their dinner party for the crime of... well, being a monkey. He's also a God hissownself, so he decides not to take this with gentle good humor. In this particular panel he's got one of the offending deities by the hair, swinging him over his head with a mad war cry... And there's one. Single. Tear. In the poor guy's eye. A small detail that makes the whole panel about twenty times funnier.

So. What's wrong with it?

I've only got a handful of nitpicks:

(MORE MONKEYS WEARING SHOES GODFUCKINDAMMIT! There's this whole big plot point about how all the monkeys have to wear shoes, PS this is awesome, and then Yang TOTALLY cut ALL the monkey's feet off on the whole second page of sneakerfied monkeys! What a friggin gyp!)

But only two real complaints:

First, while the TEEN DRAMA and the MYTH was the very model of expedient narrative efficiency, the "COMEDY" kind of treaded water, story-wise. In a Pulse interview Yang said:

"To be honest, writing and drawing Chin-Kee wasn't difficult at all. It was an exorcism. I just took everything I've been angry about since I was young and put it on paper. I was very passionate about Chin-Kee."

I hear ya, man, but by the third-or-so time we meet Chin-kee the whole story starts to feel a little TOO much like "Writer venting his spleen" and not at all like"Writer making effective decisions about application of his craft." And th' fact that the other two story strands are so damn well done makes this even more obvious.

But this by itself doesn't sink the book, or make it worse than Fun Home.

What REALLY trips up American Born Chinese is the ending. Up to the very last thirty/forty pages Yang had been telling three stories about three different characters that were about the same thing, using each of his three strips to comment on and recontextualize the others. But the end discards the subtle approach and yanks out the sledgehammer, beating the three strips into a plot-convergence.

Yang says in the same interview quoted above "I thought about doing an anthology-type book or collection of short stories, but decided it might be cooler if the three stories somehow tied in with one another. It was almost an intellectual exercise at that point, to see if I could do it in a coherent way."

Dude, next time, go with yer first instinct.

Here's the ending, trying to remain as spoiler free as possible:

The character from one of the plot-lines turns into the character from another one of the plot lines, and ends up fighting and destroying a secondary character. The secondary character of one of the plot lines ends up being the son of the main character in another plot-line, and the father character leaves HIS plot line to explain to the primary character in another plot line a lesson that that character has, as far as I can tell, already learned.

In the books favor, this all makes sense. Really.

On the downside, none of this instant interaction serves to further illuminate or tell us anything new about the books themes of race vs. culture. Nah. It's worse than that. None of this serves much of any storytelling POINT at all, really, besides highlighting th' fact that the stories all end up pretty much the same, with the protagonists finding some kind of self acceptance, either through careful, meditative review of their lives up-to-this-point or through a quick application of the old ultra violence.

(PANEL SCAN HERE, BUT ALL MY STUFF IS PACKED. I HAD TO STEAL THE OTHER PANEL FROM THE JOURNALISTA! REVIEW)

The characters don't NEED each other to come to resolution of their own unique stories. This means that combining the three doesn't just not-advance the story. It actually hurts it.

Let's say you're an author. Let's say you've written a perfectly engaging, down-to-earth, and r-e-a-w-l-i-s-t-i-c teen drama and, then 80% of the way through, you decide to throw in a bunch of magic spells and talking monkeys. Don't you think that would undercut the integrity of YOUR narrative?

Hey. Tangent that's gonna relate back to the main point pretty quick-like. Did anyone read the Paul Jenkins/Humberto Ramos mini-series Revelations that was published by Dark Horse circa last year sometimes? It was a vaguely Davinchi Codian murder mystery and at the VERY end we learn that SPOILERS the devil did it?

And it was sooooooo lame!

Same deal here. I'm a fantasy fan, through 'n through. Don't get me wrong. But if you're trying to write a story in the genre of this-actually-could-happen, well, the emergence of fantasy late in your narrative kind of renders the rest of your story moot. It feels like the author's saying "Oh yeah. This is real. This is your life, buddy. This could be you... NO IT'S NOT! HA! This couldn't Happen AT ALL! Not in a billion years! I'm totally screwing with you! HAHAHAHAHAHA!"

And that's the least of the ending's problems. The story switches from being cunning and sneaky and chock-full-o'-symbols to bordering-on-after school special in its obviousness, but, somehow in a really unclear way. One character decides he should "Be himself" and passes this advice onto another character. But since one of 'ems a magical critter and one of 'em ain't, it's hard to tell which of the multiple aspects of "yourself" that the kid should be. (Ummm.. spoilers.)

The VERY first few chapters tell us that in order to be a "Transformer" you gotta give up your soul. And although the story's referring to an actual honest to-Megatron transformer, I think we all caught the metaphorical drift, given the context. But how can you avoid transformation when you're already bein' jammed between two cultures; The answer certainly isn't "Be American" but being full-on Chinese isn't an option, either. And if you accept your Chinese-ness within an American framework (And what-the-frug THAT would mean, exactly, is another big-ass ballowax) isn't that being at least partially a transformer? So do you have to sell your soul? I gather from the reasonably-sort-of-happy tone of the ending that that's not the answer Yang's directing us towards. Mebbe I'm jes' dumb, but it seems pretty clear the kid was steered towards an obvious decision and sort of found peace, but I have no clue what the decision IS. It's all too simple and too complex at the same time, like maybe Yang HAD to get his story neatly packaged up in 240 pages.

And remember how I commented on how each of the three story strands served to subtlety comment on the others? Well the commentary's still there, after a fashion, but the subtle interaction's gone like yesterday's bathwater, and replaced by something more akin to a carnival barker megaphoning in your ear "DO YOU GET IT?!?! DO YOU!?!? IT's ALL THE SAME STORY ABOUT THE SAME THING!"

After nigh on 200 pages of assuming his teenage audience is smart enough to glom onto the thematic similarities between the three strands without bein' whacked over th' head with 'em, Yang decides that he absolutely has to make the story's overlap clear to even the dullest of readers. It's an unwise choice, and feels almost disrespectful to the audience.

I'm not sayin' that the interconnectedness was a terrible idea in and of itself; if it'd been handled with a little more cool. Like, say, the characters didn't ACTUALLY meet in the middle-ground of their own compromised reality. But, honestly, the book would've been much stronger if Yang'd simply let the characters come to their own unique resolutions, and grant them the dignity? Truth? Of their own separate worlds.

So despite it's bravery, topicality, and amount of stuff that worked really, REALLY well, American Born Chinese just didn't demonstrate the absolute perfection of craft that Fun Home did, although it was damn close up 'till 'bout page 200. But, then again, this is Yang's, what? Fourth book? And I have a feeling he's gonna get even better his next time out.