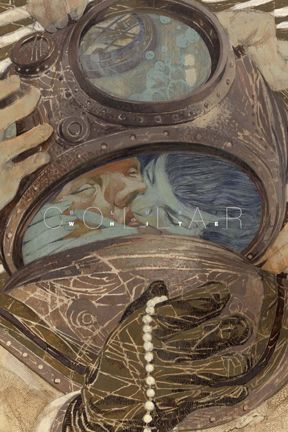

When it comes to AdHouse Books' Chris Pitzer, there's one basic fact: When he publishes a book, I know it's important to pay attention to it. So when I found out about Blue Collar/White Collar, which collects the work of award-winning illustrator and painter Sterling Hundley, I immediately contacted Pitzer to see the book and (soon after checking out the book) to get Hundley to commit to an email interview. In the course of this discussion I was pleased to find out that Hundley has plans to create his own characters and stories in the future. After reading the interview, be sure to enjoy the 10-page preview that Pitzer offers interested readers.

Tim O'Shea: In the Foreword to the book, you wrote: "In a time when access has reached the Faustian ideal, information is often confused with knowledge. I refuse to accept that appropriation and homogenization are the movements that will define our generation. The search for original thought is a journey of faith – a belief that art is necessary because it isn’t necessary. The compulsion to create is emblematic of life that has moved beyond the base functions of survival. Art is evolution." How much living and pursuing of art did you experience before realizing "a belief that art is necessary because it isn’t necessary"?

Sterling Hundley: Coming from a family that is primarily Blue Collar, I've always questioned the validity of a pursuit of the arts. You can't eat it, or use it. Art serves no utilitarian function. Having lived long enough, I've come to realize that art is as necessary as any other basic function.

O'Shea: Do you think in some sense, your academic work (you are a Professor in the Department of Communication Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University) helps inform/influence some of your work in a way?

Hundley: As a professor, I have an obligation to my students to openly share information. I am often required to explain intuition, which is, at time, exceptionally challenging. Overcoming such challenges often leads to significant growth. In addition, I begin every class with a simple question? What is interesting in the world. I look to the students to keep me informed.

O'Shea: When developing a book like this--how do you go about deciding what to include (and were there any pieces you had to leave out and you wish had had space to include)? Also how do you arrive upon on what to put where (in terms of order)--was there a flow you hoped to achieve with the book?

Hundley: Chris Pitzer served as both the publisher and the designer on Blue Collar/White Collar. I sent him initial thoughts that were anchored around individual signatures within the book that break up the various sections- an idea introduced by my friend, Jeffrey Alan Love. While the book isn't necessarily linear, it does follow a bit of a timeline in my individual growth over the years that reflected significant turning points in how I introduced new problems and went about solving them.

O'Shea: What's the background (on the creation) of My Lady Richmond?

Hundley: My Lady Richmond was commissioned as a commentary on why Richmond is a great place for young creatives. I personified cities that I've lived in over the years as young girls that I've met. With my now wife, then girlfriend staying behind in Richmond with each new pursuit to different cities- a year in Kansas City, back to Richmond, some time in New York City, back to Richmond, time in North Carolina, back to Richmond, I personified each new city as a girl that I've dated. Kansas City was kind, but a bit old fashioned, New York, fun and fast, albeit grating, but Richmond she has always been my steady.

O'Shea: You work in a variety of mediums with your art [as noted on the back of the book "from traditional (printmaking, oils, acrylics) to digital"]--how do you go about choosing which medium/materials to use when starting on a piece?

Hundley: I've always enjoyed employing a variety of approaches that are dictated by the conceptual solution of the problem that I am solving. Each new material offers a unique set of properties that can potentially compliment and enhance that message.

O'Shea: Some of the pieces included in the book include preliminary sketches allowing a glimpse into your creative process--did you hesitate at including them for revealing too much of yourself? (ignore or rephrase if this strikes you as a lame question)

Hundley: I'm an open book with nearly every process that I use. I've had concepts, approaches, compositions, and technique blatantly swiped at different times in my career. As someone that fancies myself an innovator, I have never followed fashion. Governing philosophies and big picture problems that I am pursuing are the things that guide me. Everything that I've already made lives in my past.

O'Shea: There's a section of the book devoted to your paintings. And many of those first few pieces seem to be projects where you broke the art up into equal-sized sectional squares. What was your thinking in approaching the pieces in that structural of a manner?

Hundley: Painting was a very intentional departure for me. It was an opportunity to pursue problem solving through a body of work that referenced itself, not simply a problem and solution that lived and died with a single illustration. Given the limitation of time and space as they relate to illustration, it must answer a question. Given the surplus of both of those factors in galleries and museums, I want to create paintings that ask a question. I feel that an open ended question offers room for a dialogue with the viewer that a closed ended statement does not. A painting that will hang in a museum or in someone's home should reveal itself in layers, not all at once.

The paintings began as an attempt to govern chaos. while the initial 3" x 3" panels were abstract monotypes, I wanted to employ a grid as a rigid mechanism of control. With only general themes in mind, I began to group together the shapes through light and dark values that were ultimately compiled as images that I then edited for the sake of communication.

O'Shea: You recently were interviewed by your local CBS affiliate regarding your Edgar Rice Burroughs stamp for the USPS. Is it too early to discuss what is the third stamp you're designing for the USPS? Also in the interview, you noted that not all artists understand the business side of being an artist. How early in your career did you realize being on top of your game in a business sense was almost as important as being creatively ambitious?

Hundley: The third stamp has not been formally announced, so I'll have to wait to mention the specifics. Regarding identifying the importance of business in an art-related career, I simply looked around at the number of individuals who had vast amounts of talent, but struggled to ever find their traction. What were they missing? What separated successful artists from those who could not find their path? The answer always lied in creative distinction and business acumen.

O'Shea: Anything that I neglected to ask you about that you'd like to discuss?

Hundley: I consider BC/WC to be an exclamation mark on my illustration career. I am "retiring" from illustration at the ripe old age of 35. Next up- the serious pursuit of my painting ambitions and the creation of my own characters, stories, intellectual property, where I am the author of the original content. With dozens of story ideas and themes for exhibitions, I'm ecstatic to begin this next step in my career.