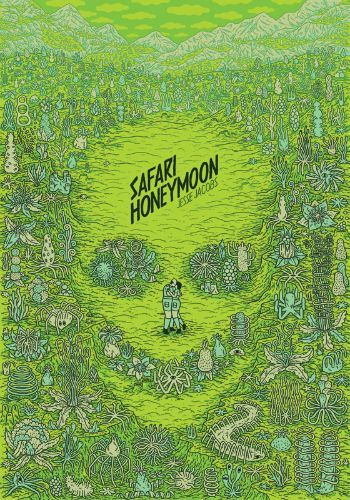

It is fair to say a newlywed couple experiences a honeymoon like no other, on myriad life-changing levels, in writer/artist Jesse Jacobs' new Koyama Press book Safari Honeymoon -- and jungle madness is only the beginning of what transpires. Jacobs' art belies any description that accurately conveys the complexity and intoxicating absurdity of his work.

In this interview, I gain insight into his creative approach, among other areas of interest.

Tim O'Shea: While comics have gained mainstream acceptance in the past few decades, I am still surprised when a book gets previewed in The New Yorker. How pleased were you to see Safari Honeymoon appear in the magazine?

Jesse Jacobs: I knew Françoise Mouly liked my drawings, as she had been in contact with me in the past. She chose me to draw the endpapers of The Best American Comics 2012, which was an honor. Still, I was caught off guard when she called me to say she wanted to feature my new book on the magazine’s website. The New Yorker is so prestigious, and to have that kind of support is beyond amazing.

How and when did your interest in edenic landscapes originate?

I’ve always loved nature. My day job allows me to visit a number of small farms, and I have been inspired by some of the people I have been meeting. Permaculture techniques, which really take advantage of the natural systems that exist in nature, I find especially interesting. There exists an amazingly intricate system that provides so much, and there are people who are succeeding in tapping into that harmony without exploitation.

Meeting all these advanced people who are striving for a balance with nature gives me a lot of hope. I think about that kind of stuff a lot and it comes through in the story and drawings.

Your non-human character designs dominate the book and enthrall the reader. How early in the development of the book did you settle upon the look of these characters?

I guess I didn’t consciously settle on the particular aesthetic of the characters, but rather drew them in the only way I really know how. It’s just the way I draw things. Even when I attempt to draw differently than my “style”, it still comes out kind of cartoony and weird-looking.

My comics usually begin with drawings in my sketchbook. I had pages full of weird characters and plants that I wanted to use in a story. The Safari idea came out of that. I needed a framework that allowed me to include all these weird things I had been drawing, and the jungle setting was perfect for that.

That’s typically how I work with comics; I begin with drawings and a story grows from there. I have a difficult time creating drawings based on a script. Maybe it’s too restrictive.

I am hard pressed to decide which of the three originally human characters intrigue me most. But I settled on the Safari Guide for that title. Was it challenging to find the proper voices for those characters?

I’m happy you like the Guide. He is probably my favorite as well. The personalities came somewhat naturally, based on each character’s role in the story. Developing characters is one the hardest things for me, which is probably why all the personalities are so exaggerated. The husband is so extremely pampered and entitled, the wife so adventurous and interested, and the guide is so very capable.

Would you ever want to explore another story in the Safari Honeymoon setting, or have you said all you wish with this story?

Before Safari Honeymoon came out, I drew a little comic called Young Safari Guide. It’s a short story about the Guide on one of his solo adventures in the forest. I could imagine myself doing another little comic like that.

I worked on Safari Honeymoon on and off for about a year or more, and got so accustomed to the characters. I think I went through a little withdrawal after the book’s completion. I’m moving on now though, and working in my sketchbook on some new comics.

What attracted you to working with Koyama Press in the first place?

I like a lot of the stuff Koyama publishes. Annie [Koyama] works so hard to give the press a presence, and she’s always releasing new material. She’s really supportive to the artists she works with, and that was apparent immediately upon meeting her.

My first published book, Even the Giants, was with AdHouse, and it went really well. Chris Pitzer is another great person in publishing, and I’m lucky to work with both he and Annie.

I like how Koyama is based in Toronto, not too far from me, so I’m able to meet with Annie and Ed [Kanerva, production and marketing coordinator] to discuss projects and production. Annie is so thoughtful and considerate; she buys me my favorite rhubarb raisin relish (which makes an appearance in the comic).

Did you ever consider doing the book in full color, or did you always envision it being colored in hues of green, given the locale?

Coloring is so daunting. Like a lot of cartoonists, I draw all my pages in black and white, and color them in Photoshop. Opening that digital color box to what seems like an infinite number of choices is unnerving. Keeping a two- to three-color palette simplifies things. I try to use color in a way that doesn’t distract from the drawings, but rather accentuates the line work.

I think of coloring comics in a similar way as I approach creating layouts. Deciding on a few different grids to be used throughout the book frees up creative choices for other things. If I have the colors and the grid layouts already chosen, it’s not as intimidating to begin a new page.

I intended from the beginning for this comic to be done in green, there was no other way.

The book is broken up with lines from talking shrubbery, such as "Within the light grows a forest so deep and sprawling that its existence cannot be contained by the physical world." What prompted you to use these lines in the story?

I wanted the talking trees to help give the forest a mystical personality. The trees with faces were some of the earliest drawings that I was certain would be included in the comic. I didn’t want them talking straight dialogue, but rather these cryptic sentences that add to the mysterious mood of the setting.

A lot of the more lyrical writing was integrated into the book in similar way that the drawings were. As I mentioned before, I tend to choose drawings from my sketchbook and work them into the comic. The same process is used with these kinds of sentences. I write a lot of stuff in my sketchbook and retroactively pick lines out that I think could work in the story.