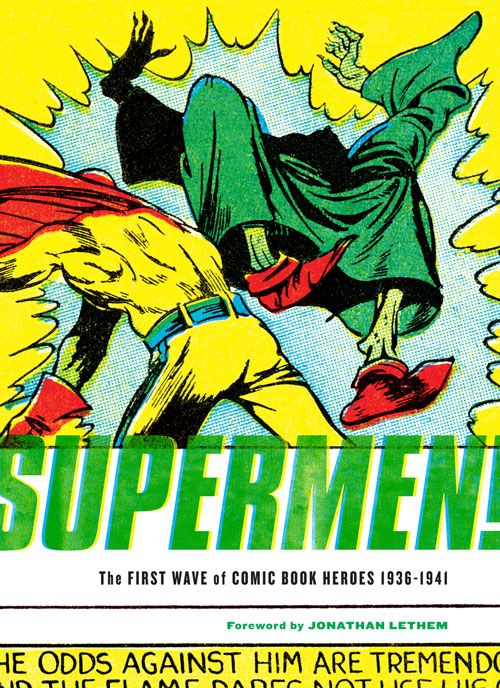

Editor Greg Sadowski's new Fantagraphics book, Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941, is a spectacular snapshot of a historical period long before comic book company events, crossovers and alternate covers or universes. As detailed by the publisher: "The enduring cultural phenomenon of comic book heroes was invented in the late 1930s by a talented and hungry group of artists and writers barely out of their teens, flying by the seat of their pants to create something new, exciting, and above all profitable. The iconography and mythology they created flourishes to this day in comic books, video, movies, fine art, advertising, and practically all other media. Supermen! collects the best and the brightest of this first generation, including Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Bill Everett, Lou Fine, Fletcher Hanks, Jack Kirby, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, and Basil Wolverton." The book sports a foreword by Jonathan Lethem. My thanks to Sadowski for his willingness to discuss his editorial approach on this project and after learning some of what did not make the first volume, I look forward to seeing a second volume down the road as time and other logistics permit. Fantagraphics also offers folks the chance to download an "11-page PDF excerpt (7.4 MB) featuring an entire story by Will Eisner and Lou Fine starring The Flame!"

Tim O'Shea: How did the foreword by Jonathan Lethem come about?

Greg Sadowski: Someone at Fantagraphics approached him, and Jonathan really came thorough - his foreword starts things off beautifully.

O'Shea: The house ads that ran in-between stories--how did you pick those to be included?

Sadowski: I tried to give the reader, as authentically as possible, a sense that he's reading a comic book from that era (albeit one with better printing and accurate registration), and the house ads are part of that experience. When I was a kid reading comics in the sixties I was always excited to see the upcoming issues shrunk down in the ads. You'd always get a little thrill later when you saw them full-sized on the newsstand racks.

O'Shea: Did you have any favorite ads among the mix?

Sadowski: I guess my favorites are the Fox ads since they had the most dynamic layouts.

O'Shea: Did any restoration work have to be done on some of the stories?

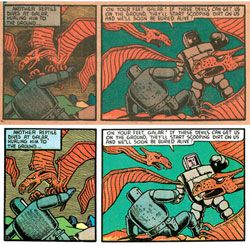

Sadowski: Yes, quite a bit, though the trick is not to let them look like they were restored. For instance, in a few panels of the Wolverton "Spacehawk" story, some of his line work turned into mud in the comic books. So I got out my black-and-white Wolverton compilations and Photoshopped in the clean line work and then added color. But that would be impossible to notice unless you saw the original comics, and I was lucky in that case because a clean version happened to be available. Every story needed work to some extent, although I always made sure to retain the character of the original comic book printing. I never liked those "Archive" editions where they bleach out the old colors and replace them with modern coloring methods printed on glossy paper. That whitewashes all the distinction out of those vintage books and transforms them into a cloyingly slick and artificial product. To me, it's mindless bureaucratic revisionism, as misguided as recoloring a poster by Toulouse-Lautrec.

O'Shea: How much research did it take to identify some of the pseudonyms?

Sadowski: Not a great deal. The detective work had already been done by historians like Jerry Bails, Ron Goulart, Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr., and Hames Ware.

O'Shea: Any idea why Al Bryant used a female (Allison) pseudonym?

Sadowski: "Allison" was actually a common male first name in those days. In fact, its English origin means "son of the noble." It wasn't until the latter part of the 20th century that it became a strictly female appellation.

O'Shea: The notes regarding the various stories were collected in the back of the book. Why did you do it this way rather than running the related text at the start of each tale? Did you not want to interrupt the flow of the stories themselves?

Sadowski: Exactly. I didn't want the Notes to horn in on things - they had to be as unobtrusive as possible. Also, formally speaking, as a "back of the book" feature they balance the front matter; the book doesn't just suddenly "die" with the final story.

O'Shea: When all is said and done, once you were done with the book, were there certain storytellers you left the project with a greater appreciation of them than you had at the start of the project?

Sadowski: I'd have to say Jack Cole particularly. Apart from the great graphics and breakdowns, Cole's three stories (which cover a nine-month period, from April 1940 to January 1941) pretty much encapsulate how comic book storytelling evolved in those early years: from being verbose, coarse, a bit stiff and self-conscious, to loose, exciting, splashy, fun. I think Cole had a profound influence on Will Eisner, allowing him to loosen up considerably on The Spirit.

O'Shea: Considering you wrote of Fletcher Hank's work on Stardust "his work would have been unthinkable only a year or two later," what motivated you to include his work in the book?

Sadowski: Well, my primary motivation was the chance to show his work (which I love) in context with his contemporaries. But it was also to underscore that this was a period when all things were equal. For all anyone knew, Hanks could have become the next Siegel and Shuster. The only way to find out was to give him a shot. Things were set in stone quickly, though, and by 1942 heroes were expected to look and behave in a preordained fashion.

O'Shea: Basil Wolverton (like many artists of this era) made some interesting choices in his art. While working on this collection, did you ever find yourself asking: "Why did the artist do that?" With Wolverton, that question entered my mind on page 156, when he introduces Galar--a character with an exceedingly prominent receding hairline.

Sadowski: Well, even Superman's hair receded in his early days. But I think it's common practice for a supporting character to appear not quite as handsome as the star. It's like in the TV show "I Love Lucy," where Vivian Vance's contract stipulated that she had to be fatter than Lucy.

O'Shea: Were there any storytellers or stories that you had to leave out due to space?

Sadowski: Several, but I'm hoping to do a second volume. Some fans complained because I left out the Will Eisner "Wonder Man" story, the one DC sued Fox over due to its similarity to Superman, so I'll have to get that in volume two.

O'Shea: This book covers the "first wave" of comic book heroes, any chance in doing a book on the second wave?

Sadowski: It's quite possible, but there are several other books I have to finish first, including a 1950s horror anthology with John Benson due out early next year, and a history of the short-lived but highly influential comic book company, Centaur. And at some point I have to turn in volume two of the Krigstein bio. That one's about halfway there.