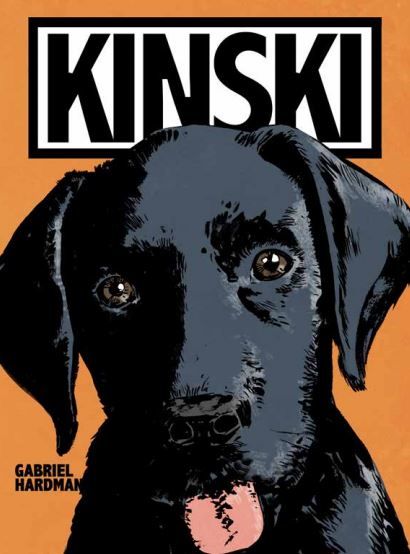

When artist Gabriel Hardman isn't drawing comics, he's drawing for movies. His affinity for films manifests itself in several ways, including his willingness to share his film knowledge via Twitter. Beginning May 15, that love of movies will be partially reflected in his new Monkeybrain Comics project Kinski (available for preorder).

It's the story of a fellow who finds a dog, and the events that unfold from there. This project is a departure for Hardman, who acknowledges Kinski has "much more of a quirky, indie vibe than any of the other comics I've done prior. Coen Brothers-esque." Hardman with a Coen Brothers bent served as great fuel for my questions (and while he initially referenced the Coen Borthers, in our discussion he's quick to also cite Martin Scorsese's After Hours and the Terrence Malick-written Pocket Money as influencing elements).

Tim O'Shea: In tackling a story that is a quirky departure from your normal fare, how did you settle upon making a dog the main catalyst of your story?

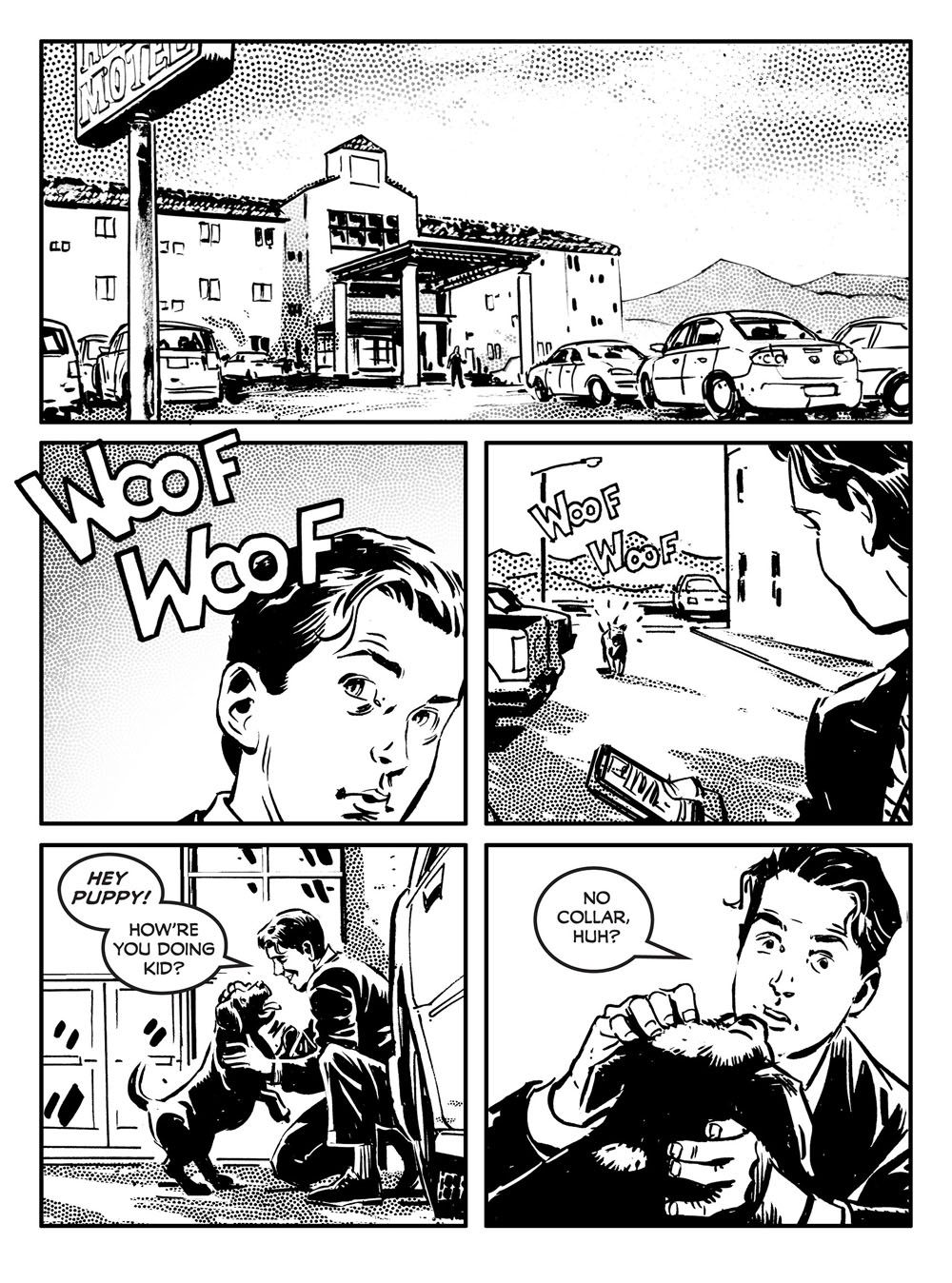

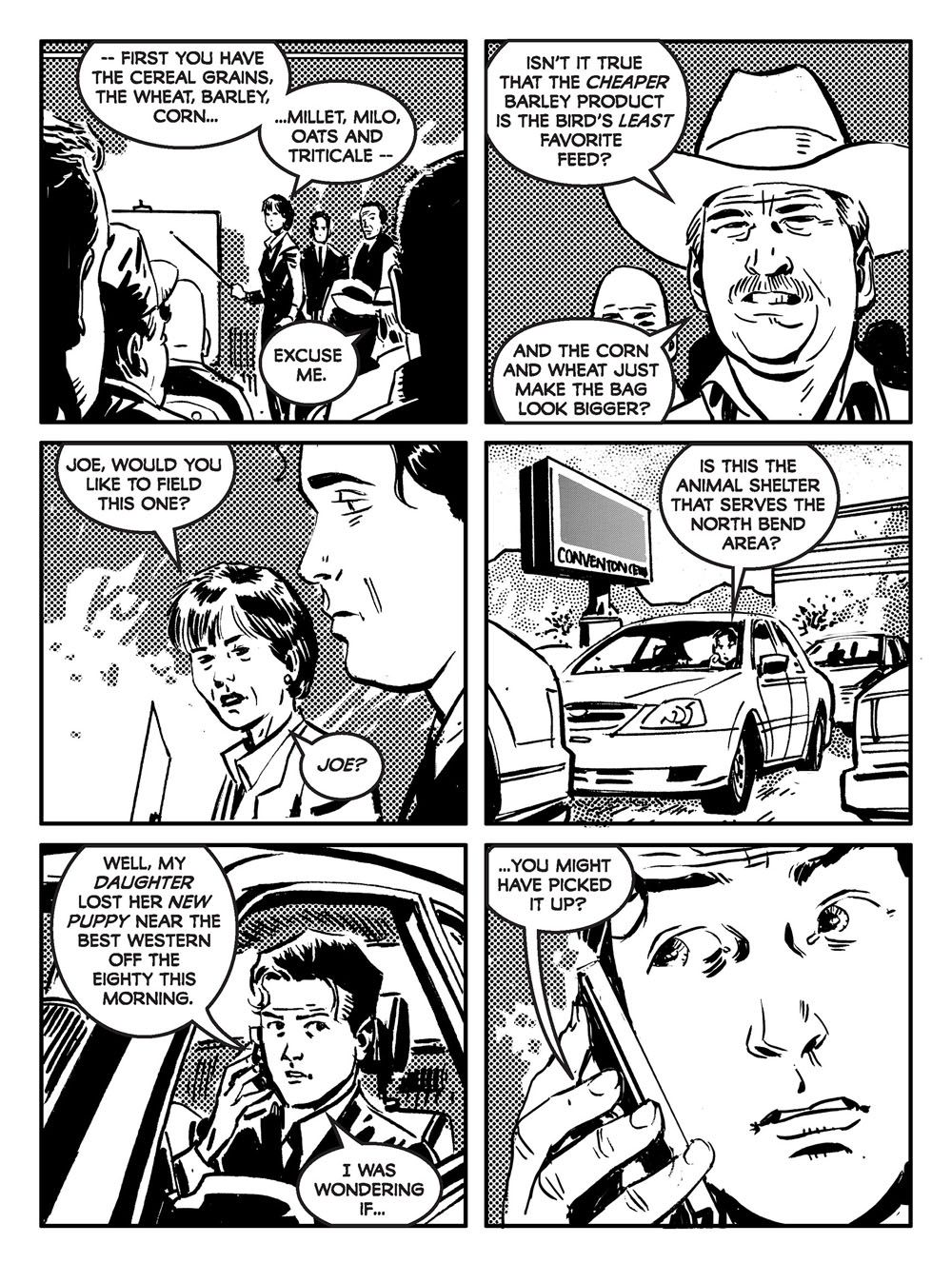

Gabriel Hardman: I like the idea of using a dog to spark the story because animals are chaotic. They don't have the same set of social rules to adhere to as we do. Dogs don't care about our problems! They can send the story off into unexpected directions. But even though Joe, the lead character, finding the dog starts the story, he's using the dog as an excuse to ignore other things in his life he's having problems with. Mainly his unfulfilling job as a bird feed rep. He decides he's going to save this dog, no matter the cost. It's a crusade! But crusades usually don't turn out so well.

And while the quirky, Coen Brothers-esque tone may seem different from my other recent work, this project was actually started earlier. I've been working on it, back burner style, for quite a while. On the surface it might seem like a radical change but underneath I think the concerns are pretty similar.

In addition to working in films, you are also a die-hard film buff. With that in mind, did you consider naming the dog Wenders, Welles or something other than when you settled on Kinski?

The dog was always going to be called Kinski. You know what I was saying about animals being chaotic? Well, the real Klaus Kinski, the actor, was nothing if not chaotic. That said, understanding the pop culture reference behind the dog's name isn't integral to the story, though there are further twists that hinge on the dogs name.

Artistically did you approach the project differently than you might otherwise?

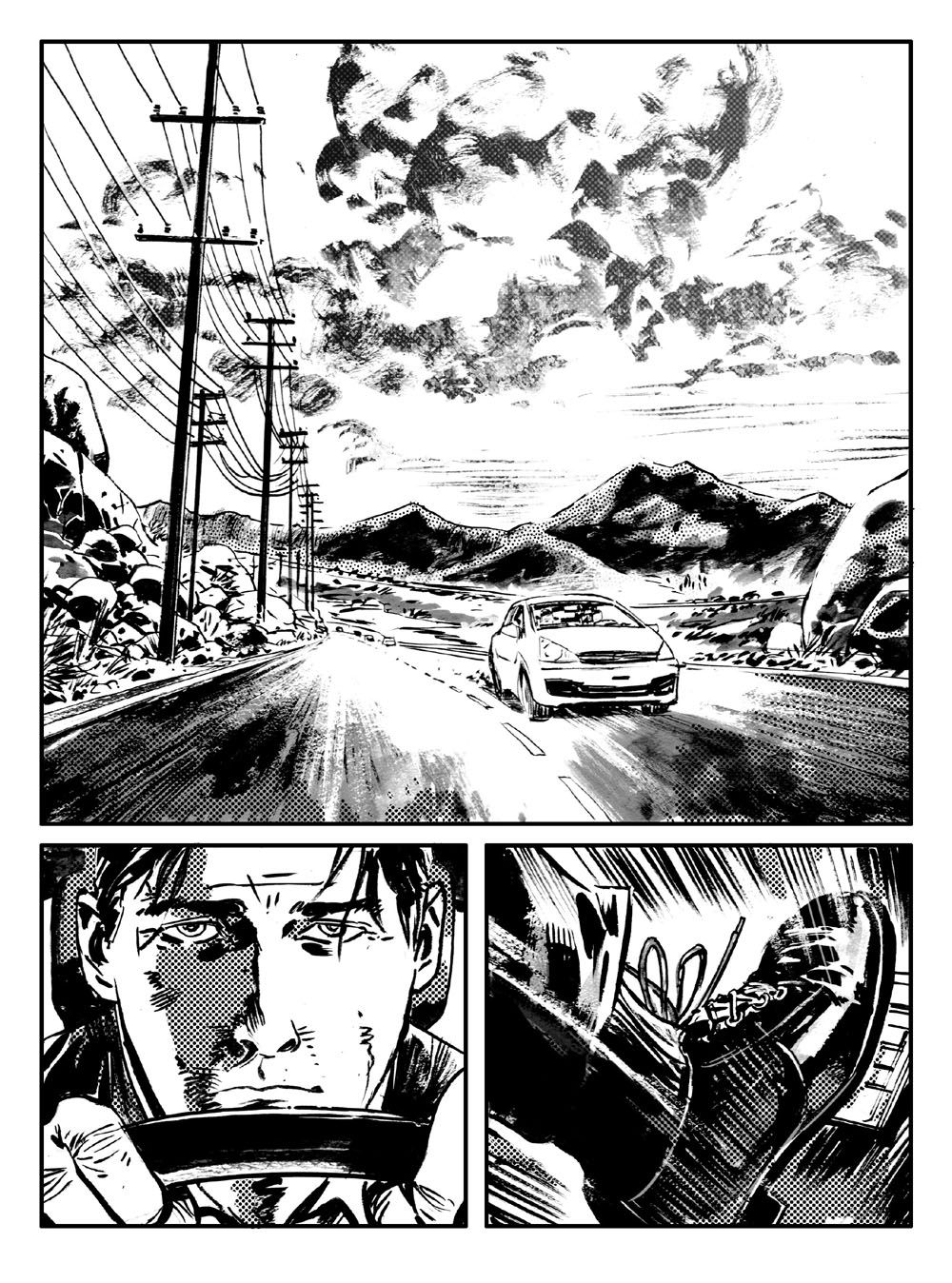

I always intended to draw this story in a somewhat simpler style than my other work. That's reflected in both the line work and the six panel grid I'm working with, not to mention sticking with black and white instead of color. It's the cartooning equivalent of shooting a film guerrilla style. Indie!

What prompted you to bring the story to Monkeybrain?

I think publishing digital-first is exciting and creatively freeing. I've been very impressed by the way Monkeybrain has taken bold steps to find a new model for distributing creator owned comics. Like all media, comics are in a transitional phase but that can be really exciting. It's something I want to embrace. I also look forward to doing the print collection. Kinski is a miniseries, and in the end I want to see its in print as a single story.

When we first discussed this project, you mentioned there's a Coen Brothers-influence in the mix here. Indulge me: Name your three favorite Coen Brothers films or characters?

Barton Fink. Raising Arizona. Big Lebowski.

And while the Coen Brothers are a good tonal reference point for Kinski, some deeper cuts like Scorsese's After Hours and the Terrence Malick-written Pocket Money are probably more direct influences.

How much does sound play a role in this story, I love your use of it in certain scenes?

Sound effects play a bigger part here than most of the other books I've drawn. It may be in part because I'm responsible for every element of this book. But I'm also telling a story without captions or inner monologues to paper over the exposition so I need every tool at my disposal to get the story across.

Back in July of last year you tweeted teaser panels from the third chapter of Kinski in which you lamented you hoped to finish the story some day. How satisfying does it feel to have it finished?

"Finished" is a strong word, Tim. But it's great to be getting the book out there. Much of it is done and it'll be great to finally get Kinski out into the world.

In terms of setting mood, how much do you enjoy doing black and white storytelling (versus full color)?

I wanted simplicity above all. Like a daily newspaper strip. Just focus on telling the story with no flourishes or distractions. But I could imagine doing a color version at some point.

I found it interesting that in a story centered on a dog, the character who initially finds him (Joe) proves to be territorial about the dog. In trying to establish that with the character, how challenging was it to not make that character quality too heavy handed?

You could characterize it a territorial but the decisions that Joe makes in this story are also not necessarily good ones. There's a lot of hubris in what he's doing and the repercussions of that will play out in the coming issues. He may even realize that his intentions are not entirely honorable and try to fix that. Of course, that'll just cause more problems.

Does it take an increased confidence in your art when you try setting emotional tone/tension in scenes without using dialogue (as happens effectively in some of these scenes)?

I think that's just what visual storytelling is about. You have to get the reader to do some work and infer what's going on in the characters heads to some extent. It's more satisfying. You can also accomplish this with an interior monologue but I don't think that's what comics do best. For me writing and drawing Kinski is my attempt to embrace some of the fun, unique things that are at the heart of comics storytelling.