Yes, it's time to check out a bunch o' big thick comics. You know you want to!

Up first is the "Essex County" trilogy by Jeff Lemire. The three books are: Tales from the Farm, Ghost Stories, and The Country Nurse. The first two came out in 2007, while the third one will be out on 1 October. Top Shelf publishes these, and the bookend volumes are $9.95, while Ghost Stories (which is longer) retails for $14.95. (As always, you can click to embiggen these scans, although some are pretty huge. Sorry!)

I read the first two volumes late last year (or possibly earlier this year; I can't remember exactly, but they were both out already) and decided to wait until the third came out to review them all at once. It's not that it's necessary to read all three - the third certainly ties in much more to the first two, but the first two largely stand on their own - but they do feature many of the same characters, and as I had read the first two in quick succession, I figured I'd wait. Yes, I'm aware you probably don't care. But I'm all about full disclosure here!

Anyway, Lemire tells stories set in Essex County, Ontario, Canada's "southernmost county". It's right across the river from Detroit, in case you're interested. With the exception of an extended flashback in the second book that takes place in Toronto, the novels show life in a rural setting, as the people struggle to make a living on the farms of the county. In the first book, we're introduced to Lester Papineau, a ten-year-old boy living with his uncle, as his mother died years earlier and he never knew his father. The second book tells the story of Lou and Vince LeBeuf, brothers who briefly played hockey together in Toronto in the early 1950s but chose different paths afterward. Anne Quenneville, a nurse, is the focus of the third book, although we also get a flashback to 1917, when her grandmother first came to Essex County (her grandmother is still alive in the book, although she's 119 years old, which stretches credulity a bit). These people cross paths with each other several times, and it's fascinating how Lemire shows events from different angles and points of view to reveal the intricacies of life.

Lester's story begins the trilogy. Lester lives in a fantasy world, always wearing a domino mask and cape, drawing superhero comics in his bedroom, and building a fort to defend against an alien invasion that he is convinced is imminent. On a trip to the gas station/general store, he meets Jimmy, an ex-hockey player who lets him have a comic book for free. Lester's uncle tells him that Jimmy is "slow," but Lester sees him out by the creek on his uncle's property one day, and the boy and man form a bond because Jimmy doesn't laugh at Lester when the boy tells him about the alien invasion. This drives a wedge between Lester and his uncle, because his uncle didn't want to take care of him and doesn't really know how. Jimmy becomes more of a father to Lester than his uncle, but Jimmy, obviously, can't be a real father to him. Uncle Ken has to figure out how to connect with Lester, and over the course of the book, he does, to a degree. Meanwhile, Lester himself has to grow up a bit.

Lemire does a remarkable job showing how Lester does grow up. There's tragedy in his life, of course, because of his lack of parents, but his retreat into his fantasy world turns out to be a boon to him, because when the alien invasion comes (and it does, rather surprisingly), Lester learns a great deal about heroism and what family members do for each other. Lemire tells the story slowly and deliberately, never rushing to the climax, allowing Lester and Jimmy to get to know each other and trust each other, so that the ending hits us extremely hard. The final images hammer the book's theme home more poignantly than text could do.

The second book begins in the present, but Lou LeBeuf, now an old man, flashes back quickly to 1951, when Lou welcomes his brother Vince and his brother's girlfriend Beth to Toronto, where they'll both play for the Toronto Grizzlies, a minor league hockey team. Lou is a decent player, but Vince is a phenom. Unfortunately, Vince doesn't like the city and can't wait to get back to Essex County, take over the family farm, settle down with Beth and pump out a bunch of kids. What's fascinating is that Beth doesn't necessarily share this vision - she likes Toronto a lot, and because there has to be some sexual tension, she and Lou have a spark between them. This culminates with a liaison on the roof one night when Vince is asleep. Vince leaves the team after the season and goes back to the farm with his now-pregnant fiancée, and Lou stays in Toronto and doesn't return for 25 years. When he does, he meets his niece - there's always some doubt whether she's his daughter, although the characters insist it isn't - but gets in a fight with Vince and leaves again. Tragedy strikes the family, of course, and Lou ends up living with Vince, and the two brothers get old together. In the end, only Lou is left, and he continues to drift in and out of reality as he constantly revisits the past. It's a tragic story, yes, but Lemire allows Lou to revisit the time in his life when everything was perfect, and it's a beautiful moment.

The third book focuses on Anne, whom we first meet in Ghost Stories, as she is Lou's nurse in that book. This book ties everything together, as Anne knows what happened to Lester's parents and tries to get his Uncle Ken to tell Lester the truth. Meanwhile, we learn Lou's fate, as well, plus we get the flashback to 1917, when Anne's grandmother, a nun at the time, had to lead the orphans in her care across miles of a forest in winter after their orphanage burned down. She finally makes it to Essex County, and this is an event that sets in motion everything else, as her oldest orphan turns out to be Lou and Vince's father. Anne, perhaps not surprisingly, is dealing with her own family problems, as her teenaged son is becoming increasingly distant and she doesn't know what to do.

Lemire does a remarkable job tying all of these stories together. It's a wonderful series, as Lemire manages to delve deeply into family relationships without being obvious about it. The characters have been hardened by life, and they're stoic in the stereotypical farmer way, even if they're not all farmers. They can't say the things that they need to say to the people they need to say them to, and it makes their lives even more tragic. Lemire shows how the past informs the present and traps these people, but also offers them comfort when things go bad. It's fascinating how Essex County becomes a haven for these lost souls, from Sister Margaret Byrne, who leads her charges to the county in 1917 while carrying an illicit child in her womb, to Vince LeBeuf, who could have made it to the NHL but didn't want that life, and even to his brother Lou, who lives in Toronto for decades before finally returning to the farm after it's too late to make amends.

Despite the tragedy in the characters' lives, Lemire's books aren't depressing. They're about life, after all, so there are several nice parts. Lester grows up, and although not everything works out for him, he comes to understand the sacrifices grown-ups make to give children a decent life. Anne finds comfort in caring for the elderly, and even though she has questions about whether she's really helping, she still keeps trying. These are people who struggle in a hard place, but the point is that they try. Lemire does a lot of interesting subtle things, too. The way Lester sees the world in the first book makes an event in the second book more dreamlike, as we're pretty sure it doesn't actually occur. But it gives Lou a way to come to terms with his life and what he's done, and it's a sweet moment. Lemire never pushes his themes on us, allowing the lives of these characters to play out before us and reveal their secrets slowly.

Lemire's bleak art is fantastic, as well. Even though the comics take place in the present, the book has a stark, frontier feel to it, as if the characters live far from civilization. The hard years are etched on their faces, and it's marvelous to gaze at the characters and see their emotions come out. These are real people with real lives, and Lemire does a wonderful job with them. We get a real sense of place, too, whether it's Essex County or Toronto. No matter where these characters are, we get the sense of isolation they feel - on the farm, they're isolated by their loneliness, while in the city, they're isolated by the lack of family. Lou feels this and expresses it, but Lemire does a wonderful job with the longer shots of both the city and the farm to give us a real feeling of how alone these people really are. He also does a magnificent job blending reality with fantasy, which is part of the point: these characters find comfort by escaping their lives and imagining something better, either in make-believe or the past, and Lemire is very good at shifting easily between the two.

The Essex County trilogy is fantastic. You don't have to read them all (although I wouldn't suggest you start with The Country Nurse) to get a good story, but if you do read them all, you get a much bigger tapestry. This is a wonderful set of comics, and I can't recommend them enough.

Our next selection is Too Cool to be Forgotten by Alex Robinson. It's another Top Shelf book and will set you back $14.95. However, yours probably won't have a cool Alex Robinson drawing inside it:

Suck on it, losers!

Oh, pardon me. That was rude.

Whenever I read a comic that far cooler people than I like, I get nervous. Our Dread Lord and Master, who, as we know, can emasculate anyone with but a thought, likes this comic quite a bit, and I'm sure the folk at Rocketship, the Universe's Awesomest Comic Book Shoppe, do as well. So I get nervous, because what if I don't like it? Can I deal with the humiliation of not having as good taste as those people? I mean, what if I don't like this but I continue to like Moon Knight? Am I even allowed outside the house anymore? (And please note: I'm not being sarcastic. Rocketship does sound like an excellent comic book store. It actually makes me wish I lived in Brooklyn, something I never thought I'd ever think. And it always makes me think of the Dead Milkmen song. I can't help it!)

Well, I don't think I'm going to endure the wrath of my superiors, because this is quite good, even though it has a few nagging problems that I'll get to. It's a LOT better than I thought it would be, mainly because Robinson doesn't make it about the Eighties as much I feared, and therefore it's not just a nostalgia-wank about how cool Def Leppard was (and let's face it, they were pretty cool around 1983 when Pyromania came out). In case you don't know, the conceit of this book is that Andy Wicks, a 40-year-old smoker (the "present" in the book is 2010, so he was born in 1970), goes to a hypnotist to quit his vile habit. When he goes under, he finds himself back in 1985, but with the mind of a 40-year-old. If you're rolling your eyes and thinking "Wasn't that a crappy Francis Ford Coppola movie?", well, you'd be right. But that doesn't necessarily make it a bad comic, or even a bad idea! (Jim Carrey and Joan Allen are in that movie, by the way. How weird.)

Andy immediately tries to figure out what's going on and why he's in 1985. He eventually decides it's because he was transported to the time right before he took his first cigarette, so if he turns it down, he'll never start smoking and therefore he'll be cured. Unfortunately, it doesn't quite work out that way. He skips the cigarette but stays in 1985. The book then becomes a quest for Andy to figure out how to get back, because he misses his wife and kids. Robinson does a nice job making us wonder if he actually will get back, even though we're fairly certain he will.

Robinson's art is very good, as he immerses us in this time period without making it too obnoxious. There are a lot of characters, but we're never lost as to who they are, because Robinson gives them all such interesting (or at least distinctive) personalities. The style of the times is there, as well, but Robinson manages to integrate it so much into the storyline that it never overwhelms us with its "Eighties-ness." I'm reminded of Jacob's Ladder, which takes place in the 1970s but is never obnoxious about the fashions and music of that time (and, as an aside, I'll ask what I've asked before about that movie - how did Adrian Lyne manage to make something so freakin' brilliant when every other movie he's ever made is schlock?). We're aware that we're in 1985, but Robinson does a good job in keeping the focus on the people and not the time period. Later in the book, he starts to flex his artistic muscles a bit more, and there are two back-to-back pages that show the faces of two characters blended with events that are occurring in Andy's life that are simply staggering. When Robinson gets to the emotional payoff of the comic, the art becomes very minimalistic, which matches the rawness of the scene. Plus, he pulls some nice tricks with Andy's 15-year-old and 40-year-old self, switching from one to the other occasionally to show that the 40-year-old is thinking like a 40-year-old instead of trying to act like a 15-year-old. It's very effective.

The story is good, too, as Andy tries to figure out how to get out of 1985 without screwing up his own past too much. The nice thing about the way Robinson sets this up is that we recognize that all 15-year-olds are a bit screwed up, so whenever Andy says something that makes no sense (because he's saying it from a 40-year-old perspective), nobody bats an eye. He's just a crazy kid, after all! The fact that he's a 40-year-old is fascinating, because it leads to situations like when he tries to befriend a kid that his peers want nothing to do with. Andy, far removed from a clique mindset, can't understand why no one wants to talk to the kid. Of course, Robinson can't escape the cliché of pointing out that he's learning things he'll never use in "real life" (which is annoying because a lot of high school doesn't teach you things you need in real life, but it does teach you how to think analytically, which teachers - at least the teachers I have interacted with - understand), but it's a quick thought, and Andy is angry, so I'll forgive it. For the most part, the dialogue is good (I was a bit worried when Andy first arrives in 1985, because so much of the dialogue was along the lines of: "So, I don't think we should, like, use it then. I think the whole idea is that it's, like, real, the way it really was," but luckily Robinson is just doing that to establish a mood, and he soon drops the affectations, which would get annoying extremely fast), but where the book breaks down a bit is that Andy thinks a lot about his situation. What do I mean? I mean we get a LOT of thought balloons breaking down what's going on and what he feels about it. In other words, there's a lot of telling, not showing, and it slows down the narrative a lot. Occasionally we need some thought balloons, of course, but a lot of times, Robinson tells us stuff we already know or can easily figure out. I hate to compare this to Lemire's work, because it should stand on its own, but in those books, the silence is almost painful occasionally, but we can read everything the characters feel on their faces. Robinson's book goes a bit too far in the other direction, and it lessens its impact a bit.

The last thing that bothered me with regard to the story is the climax and the events leading up to it. When I took writing classes in college, one of my teachers gave me an interesting piece of advice. He told me that the writer should never know more than the reader and the characters. What this means is that when the writer learns something about the character, he should let the reader know. You may think this is the dumbest advice ever, because how would people write murder mysteries if they wrote down the killer immediately when they figured it out? Well, in strict genre fiction, it probably doesn't work all that well, but the point is that authors shouldn't deliberately mislead the reader, because it's cheating. I'm going to try to apply that to Too Cool to be Forgotten without giving it away, because the ending is quite powerful, but it feels like cheating on Robinson's part. Andy seems surprised when he remembers why 1985 is so important to him. This is despite several people reminding him obliquely (so as not to ruin it for us) about how important it is. The first time this happens, he kind of blows off the person reminding him, but it happens so often without him understanding what's going on that it's obvious that Robinson is simply withholding this information so that when we finally learn what it is, it hits us harder. Once we learn what it is, Andy's (and Robinson's) obfuscation becomes much more obvious, and it lessens the impact of the ending. Remember, this is 40-year-old Andy we're talking about, and no matter how freaked out he is by finding himself in 1985, there's no way he would forget what happened that year. We have no indication that he's some self-absorbed jerk, so why does he act like one? Because Robinson is keeping things from us to make the ending more powerful. This story doesn't need a "twist," because the way it unfolds is good enough, even if we could guess what will happen. If I told you what happens at the end (I'm not going to, by the way), it would still be a worthwhile book, because Robinson's prose is so good.

Sheesh, I do go on, don't I? Anyway, this is very much worth your 15 dollars. Yes, I had some issues with it, but it's a marvelous look at adolescence and how things that happen to us in our past have huge effects on our present. Sure, we already knew that, but it's interesting to see it in action!

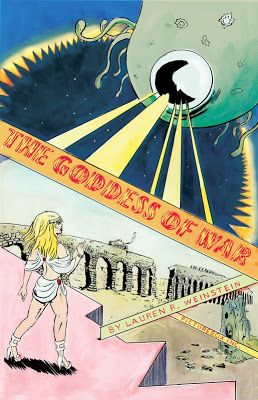

Moving along, we come across The Goddess of War, Lauren Weinstein's monstrously huge comic, which is published by PictureBox and costs $12.95. I met Weinstein at San Diego and, as usual with creators I meet, she was very cool, so I went into this wanting to like it a lot. That's always a problem, when I go into something with preconceived - either positive or negative - notions about a comic. But I try to overcome it!

There's kind of a big problem in this book, and it keeps me from loving it completely, but for the most part, it's the kind of comic I would love to see more of. Weinstein cuts loose on a story that shifts from the Goddess of War's home (which is shaped like a head and is called, naturally, the Head Cave) to outer space and other dimensions to the border between Arizona and New Mexico in 1861 to illustrate a conflict between U. S. soldiers and Cochise. Valerie (the Goddess; it's a play on "Valkyrie") is tired of her job, so she seeks an idyll with Cochise, in a sex scene between her and the Apache that exists in all times and all dimensions, so she can visit it whenever she wants (so can he, actually). But Valerie can't stop being the Goddess of War, even when she wants to, and this leads to, well, war. Meanwhile, her bosses send a pumpkin-headed evil dude to find her and make her work, but he has other ideas for Valerie.

It sounds hallucinogenic, and it's meant to be. Weinstein does a wonderful job with the layout of the book, filling each page with details and designing the book like a visual funhouse. The book is colored in green and white, but scattered throughout are gorgeous full-page drawings that look like charcoal (it beats me if they are, but it looks that way). It's a wonderful change of pace from the rest of the book. On a lot of pages, panels loop around others, and when Valerie and Cochise have sex, it's a phantasmagoric Möbius strip of a page. The book looks amazing, and Weinstein adds a nasty sense of humor to the proceedings, as we get the aforementioned pumpkin-headed killer, a Universe Eater, a groundworm that Valerie rides into space, and a Valhalla that looks like a circus. Why not?

Weinstein does bring some serious topics into the book, as Valerie is, after all, the Goddess of War. She really enjoys war, as well, and Weinstein's scenes of conflict are horrific but weirdly humorous, as they become almost surreal with cartoon violence. The scenes with the Americans and the Apaches take on a weird comedic feel even though we know it's all going to end in tragedy, mainly because Valerie's involvement, as she takes perverse pleasure in making the two sides misunderstand each other and therefore causing more mischief. We know how tragic the confrontation between the two cultures was, and to see it as nothing more than a game of the Goddess is creepy but effective.

I mentioned that I have a big problem with the book, and that's the writing. Weinstein's plot is interesting, and her storytelling skills are very good. As a writer, however, she falls short a bit. The dialogue in the book is flat and uneven. For the most part, it simply conveys information, which isn't a bad thing necessarily, but it's dull to read and doesn't establish any characters. Valerie is the only interesting character, and when the book is about her relationship with Cochise, that's a problem. Cochise, the Americans, and the other Apaches are ciphers for the most part, and it makes the book more boring than it should be. This is not a dull book by any means, but reading the dialogue slows it down, because it's stilted and dry. Even the more outlandish charactes, like Xixixi (the pumpkin-headed dude), speak as if they're simply mouthing lines they don't believe in. It's frustrating, because the book is such a joy to look at and the overall story is fascinating, but it drags when it comes to the dialogue.

It's not enough for me to say you shouldn't buy this, because it's almost a perfect example of what the art form can accomplish. It would be too big-budget and literary for a feature film yet too visual for prose. It's utterly unlike anything you've ever seen, and it's a weird meditation on what makes people fight and why we can't seem to stop. It's also bizarrely funny, looks wonderful, and features Nebulon the Universe Eater! Come on, who doesn't love Nebulon? It's frustrating that the writing isn't better, but it's still a worthwhile comic book. (It's also the first of a series, in case you're wondering. I don't know how many issues Weinstein plans.)

All right, we have to move on, and we find the latest Eddie Campbell book in the queue! Campbell provides the art to The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard, and he co-writes it with Dan Best. It's from First Second Books and is $16.95. But is it worth it????

Well, it's an Eddie Campbell comic, so it's worth it almost for the art alone. Campbell's painting is always a joy to see, but when he cuts loose a bit, like he does on this comic, it's even more breathtaking. He blends the main story with news clippings, double-page panoramas, journal entries, and one eerily gorgeous page that's almost completely purple. The story of a circus performer in the late nineteenth century fits Campbell's kind of antique style (that's not a criticism, by the way), and he drenches the story in glorious color, which makes it pop much more than Campbell's previous book, The Black Diamond Detective Agency (which is also very worthwhile, too). The color works well because when the story takes a dark turn, the colors follow suit and help change the tone of the book. It's a brilliant comic to look at, and if you've only ever seen Campbell's art in the black-and-white From Hell, you should check this out.

The story starts out one way and quickly goes in all sorts of directions. The famous trapeze artist, Jules Léotard, is famed throughout Europe. But then he dies. (This, by the way, is true - Léotard was 28 when he bought it in 1870.) His nephew, Etienne, is by his bedside when he dies, and Jules tells him, "May nothing occur" before dropping off the twig. Etienne, who does not appear to be the sharpest tool in the shed, decides that his uncle had nothing further to say, and that he wanted his nephew's life to be without occurrence. Of course, a few pages later, Etienne embarks on a life of adventure, ignoring his uncle's advice. And the book becomes odder and odder.

By "odd" I mean the most normal thing in this book is Etienne taking a balloon into Paris soon after Jules' death. This is strange for a couple of reasons: the Germans were in the middle of besieging Paris at this time (the Franco-Prussian War was in full swing), and Etienne's balloon, unbeknowst to him, had a painting of someone mooning the troops on it, so the Germans were trying hard to shoot it down. He takes over his uncle's identity, even though he has no experience on the trapeze, and for the next 20 years tries to make the circus work, with varying degrees of success. Then the book takes an adventurous turn, as Etienne's sidekick, Zany, is convicted of stealing the Mona Lisa and sent to Devil's Island. Etienne and his surviving troupe (not everyone lives through Etienne's attempts to make the circus profitable) decide to rescue him, so they head to America ... on the Titanic. Oh dear. Finally, in the 1930s, Etienne inspires two young men named Joe and Jerry when he flies on the trapeze dressed in familiar red-and-blue garb. Unfortunately, he's kind of old by then, and things don't work out so well.

The plot is all over the place, but that's not really important. The book is about discovery, after all, and therefore the plot becomes secondary to how Etienne lives his life. He is infinitely enthusiastic to the point where we might consider him a bit unsound in the head, but it's a joy to track him as he zips through life. Campbell and Best reach a point in the book where they step back and allow Etienne to dream. He dreams of the creators of the comic, who are out of ideas, while his uncle Jules also appears and explains how Etienne is the perfect man of the future. This leads to one of the better time skips you'll ever see (not as good as the one in Citizen Kane, but still pretty good), and in his dotage, Etienne comes to understand what Jules meant. It's a meditative book about what makes life worth living, and although some horrible things happen (a scene involves piranhas), it's a joyous comic because Etienne always wants to experience life. He's a hero precisely because he doesn't actively seek to be one. He just makes friends and believes that one stands by their friends through thick and thin.

This is a marvelous comic, a beautiful one to look at and one that seems silly (and it is, to an extent) but is about deep truths. You know you love Eddie Campbell, people!

The final book in this post (I have to finish it at some point, even though I by now have a bunch more graphic novelly type things to read, so another post will be forthcoming!) is a light-hearted collection of strips. David Malki! (yes, you need the exclamation point, damn it!) and Dark Horse bring us Wondermark: Beards of our Forefathers, the first book of strips from the web comic. It's 15 bucks, which, as usual, might seem odd for something you can get for free on-line, but there's a bunch of neat extras and commentary, so I think it's worth it. Plus, if you're a Luddite like me, you hate reading comic strips on the Internet. It ain't tangible, dagnabit! What the crap?

Anyway, it's pretty much impossible to review this. It features characters that are old-time daguerreotypes from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, posed in the strips and spouting absolutely crazy jokes. It's completely kooky, and completely hilarious. Even the strips that aren't that funny are so bizarre that you can't help but chuckle at them. Plus, there are some extras by guest artists, a long-form story (eight pages) and a prose story. Here, just to give you a taste, are some of the strips from the book. Or you could go the web site and check out Malki!'s style.

Why wouldn't you buy the book? Doesn't everyone need a laugh in these uncertain times????

As I mentioned, I have a bunch of other stuff to review, but I'm catching up. I hope you check some or all of these books out, because they deserve your hard-earned coin! You know you want to buy some of these! Yes you do! You can't resist!!!!!!