Each day this month I will be profiling a notable political cartoonist. Since the choices are vast, I've decided to slim the numbers down a bit and eliminate living cartoonists. Perhaps I will do a current political cartoon stars in the future.

Here's an archive of the artists mentioned already.

Today we look at a French cartoonist who took on the King!

Enjoy!

Honore Daumier was born in Marseille in 1808. When he was a young child, his family moved to Paris, mostly because of the higher cultural society that existed in Paris (Daumier's father was trying to make it a a poet).

Daumier showed artistic promise from a young age, and would ultimately end up at the Acadamie Suisse. After graduating, he began doing standard lithography work, including advertising.

He joined with another young lithographer, Charles Philipon, to launch a newspaper La Silhouette, that included lithographs and caricatures. The newspaper only lasted two years (1829-1831), but it was enough to get the editor (not Philipon) thrown in jail in 1830 for six months, after Philipon inserted a leaflet within the newspaper depicting the deterioration of the popularity of Charles X, who was soon to be overthrown (Philipon left it unsigned so he avoided the fate of his editor).

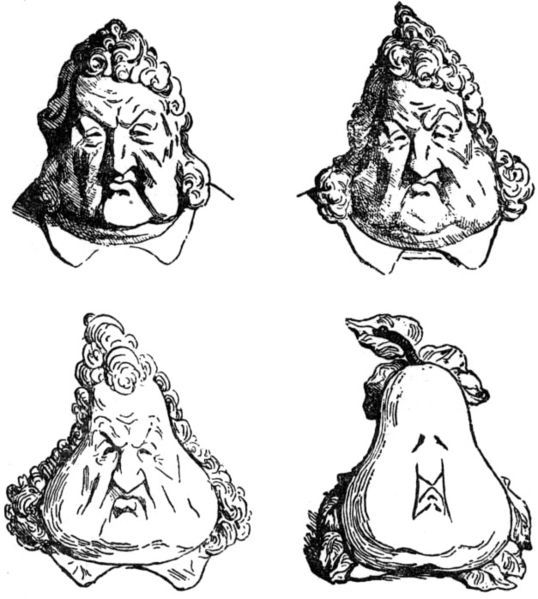

Daumier later reworked the sketch to depict the similar deterioration of the popularity of Louis Philippe, who was accepted over Charles X in 1830 quite kindly by the French public initially.

Charles Philipon then launched the comic magazine, La Caricature in 1831, and Daumier joined up, and soon the journal was in direct conflict with the Louis Philippe, who had become King of France in 1830.

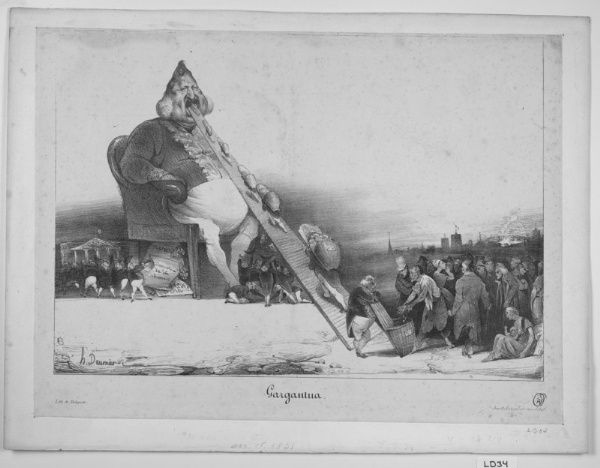

Daumier soon saw the King's ire aimed at him, when Daumier produced what is likely his most famous drawing, where he depicts Louis Philippe as Gargantua, feeding off the toil of the peasants of France.

La Caricature was closed by the French government, but Philipon soon founded a new avenue for their views, Le Charivari.

They would often be fined by the government for their actions.

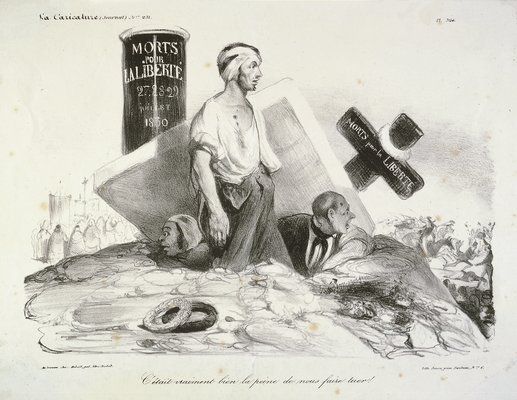

In fact, around this time, Daumier produced another famous drawing, this time in protest of the actions of the French National Guard, who killed 19 people in retaliation for the strike of silk weavers in Lyon in 1834.

This lithograph, which chillingly demonstrates the foul murder of innocent residents, was actually produced and sold to raise money to pay for their fines. Philipon and Daumier would do this fairly frequently (Daumier produce lithographs that would be sold to pay off their fines).

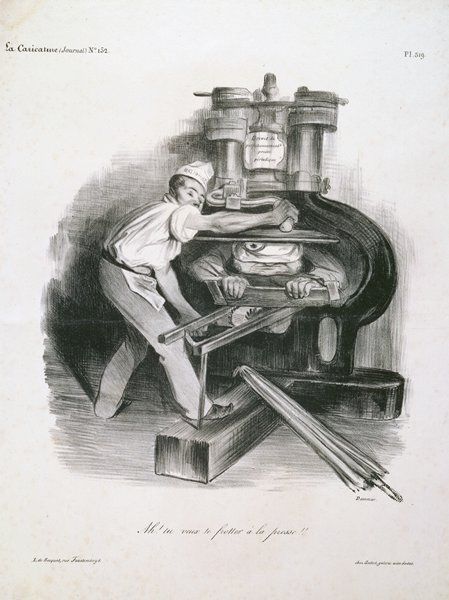

Philipon and Daumier knew the power they weilded, as seen in this drawing, where Daumier shows what prints can do to evil people (showing a printing press destroying a king pretty clearly meant to be Louis Philippe)...

Some of Daumier's other classic political cartoons from the time depict the ghosts of the original French Revolution, aghast that the current state of France is what they died for...

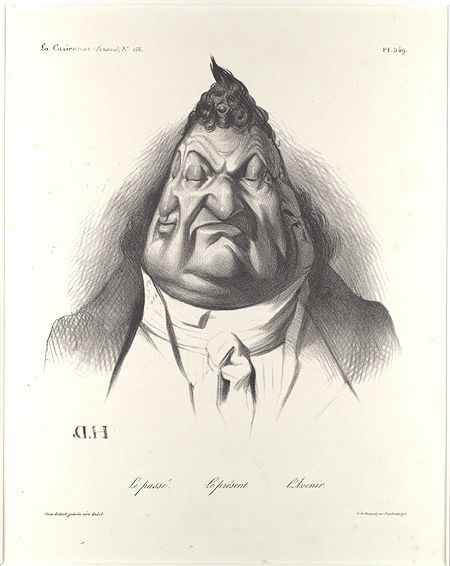

Or showing Louis Philippe showing the people of France what the past, present and future of France looked like...

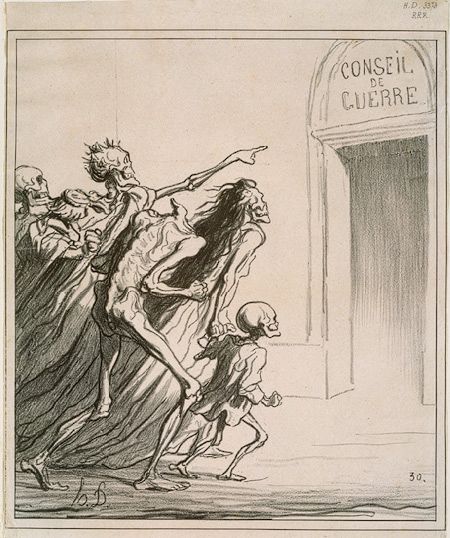

Or this fairly straightforward depictions of skeletons descending upon France's Council for War...

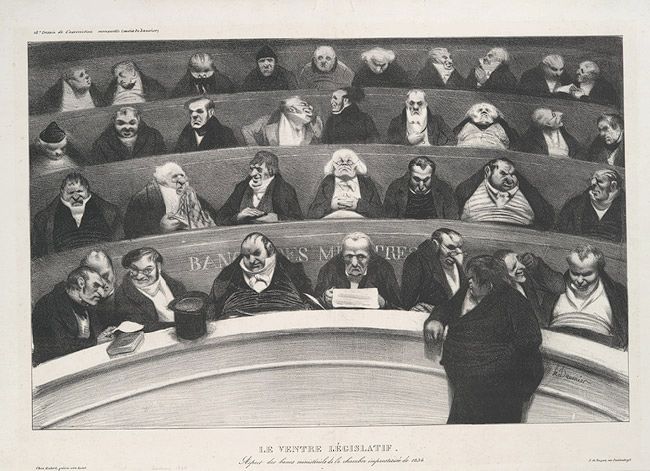

Or this also fairly straightforward depiction of the French Legislature in 1834, bloated and inattentive...

In July 1835, Louis Philippe survived an assassination attempt, and the French government used this as a pretext for banning political cartoons.

That avenue closed to him, Daumier then turned instead to social satire.

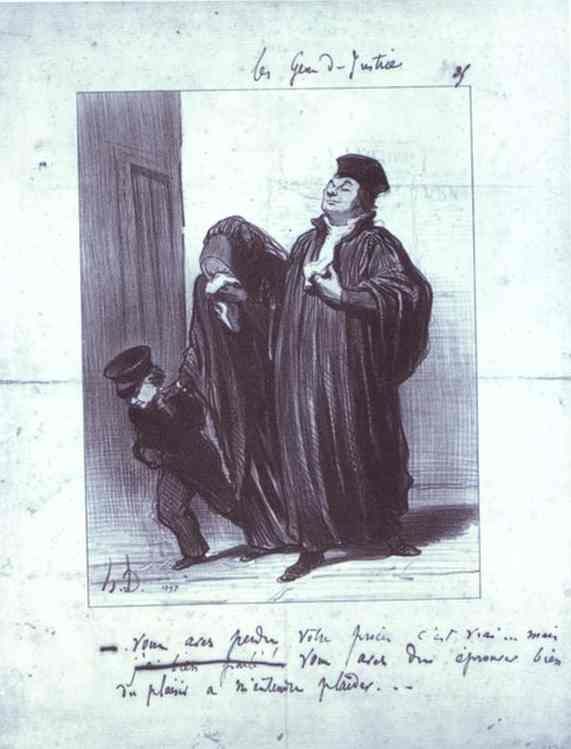

Like this piece, showing a lawyer apologizing to his client for losing, but at least they were able to witness his brilliant delivery of their case!

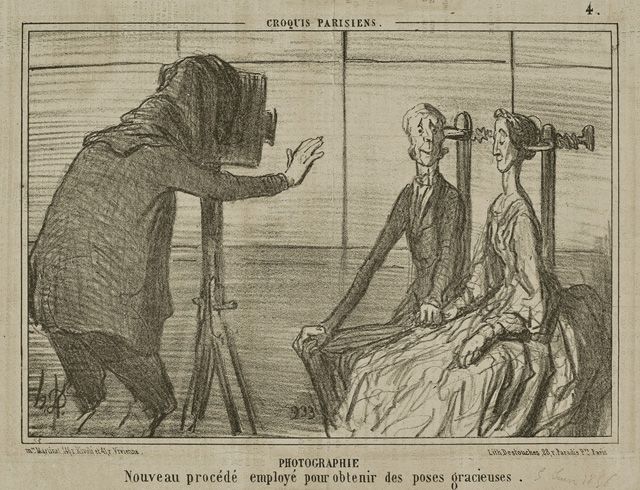

Or this piece, depicting the lengths the bourgeois society would go to look good...

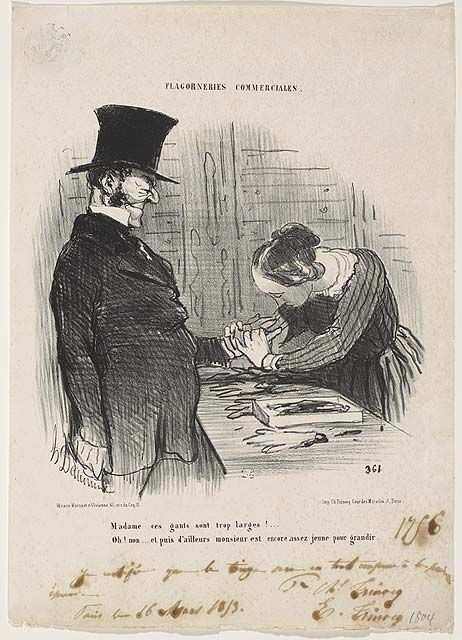

Or this general "boy, this rich guy is a jerk" piece...

Daumier was highly concerned for the state of the lower classes of France, and one of his most famous paintings depict the situation of the "Third Class," showing their daily travels...

Later in life, Daumier would turn mostly to naturalistic paintings. They were not as well liked back then compared to his drawings, but have gained more admirers over the years (Daumier was a noted sculptor, as well).

At his death in 1878, Daumier's paintings were JUST beginning to get some appreciation, so that's nice to see before his death.

Thanks to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts and The National Gallery of Canada, for the images used in this piece.