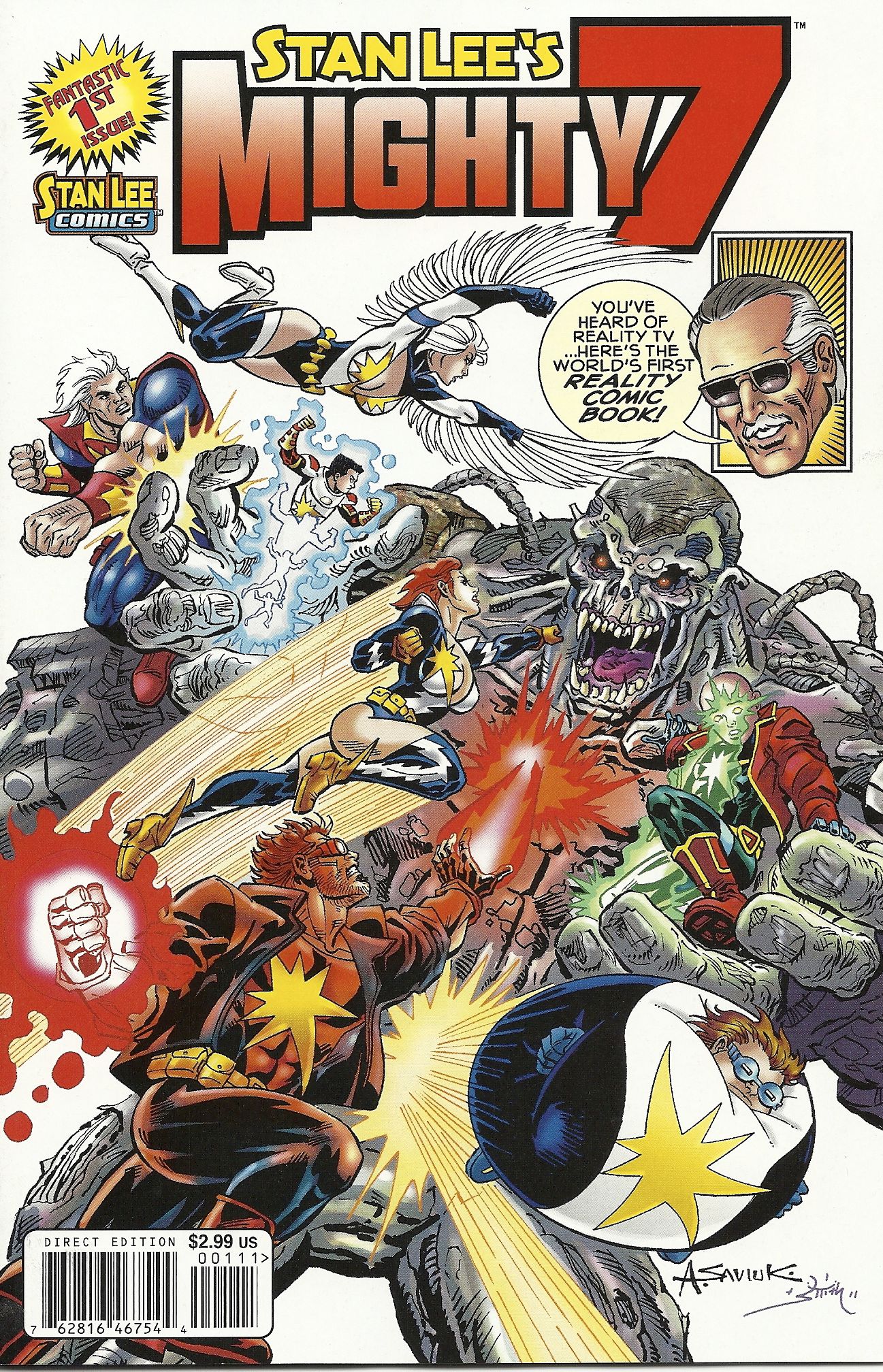

Stan Lee’s Mighty 7 #1, which bears the logo "Stan Lee Comics" on the cover but is published by Archie Comics, is, as you may guess from the cover—which also features Stan Lee’s floating head exhorting one of the book’s virtues—is a new Stan Lee joint.

It is a pretty bad comic book, and I’d go so far as to say that it’s a remarkably, even exceptionally bad comic book. But there’s still an irrepressible, hard-to-hate charm about the entire endeavor.

That’s probably down to the magic of Stan Lee. At this point in his career, the guy’s entered into a sort of lovable old rascal phase, and I often find myself forgiving him a lot in the same way I forgive older relatives and relations a lot, putting negatives down to either “Well, he’s old” and “But think of what he’s done in his life, he deserves some slack.”

That, and there is a genuinely inspired idea here, although Lee’s floating head does a poor job of selling it on the cover (and Lee’s back-of-the-book editorial does a worse job of it). The contents of the book orbiting that one inspired idea are so completely generic and derivative that I kept wondering if they were intentionally so.

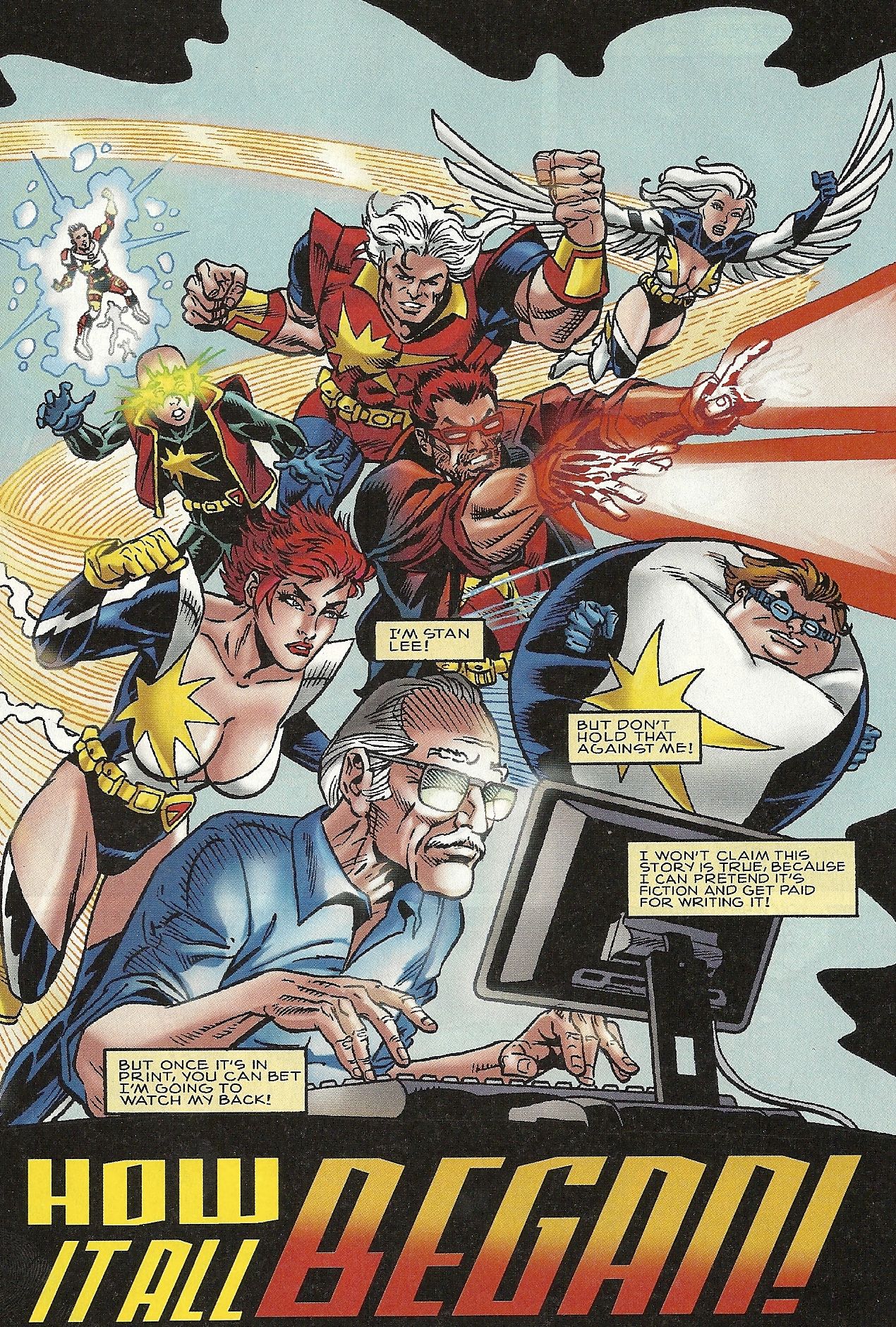

Let’s back up a moment. The book opens with a splash page of Stan Lee at a computer, the title characters striking various action poses behind him. Each is wearing a matching symbol on their uniform that looks a bit like the Legion logo’s starburst, sans the big L.

That similarity is emphasized by some of their costumes and powers. Each has a fairly standard issue superpower—super-speed, shrinking, energy blasts—although one is a winged woman with a costume cut like Dawnstar’s, and one of them has Bouncing Boy’s bizarre turn-into-a-ball power.

From there, the book divides into two basic threads.

The first takes place “On a distant planet in a distant galaxy,” where bad-boy antihero Blastok, who wears sunglasses, a leather jacket and has a soul patch and stubble, decides to play “judge, jury and executioner” on a bad guy.

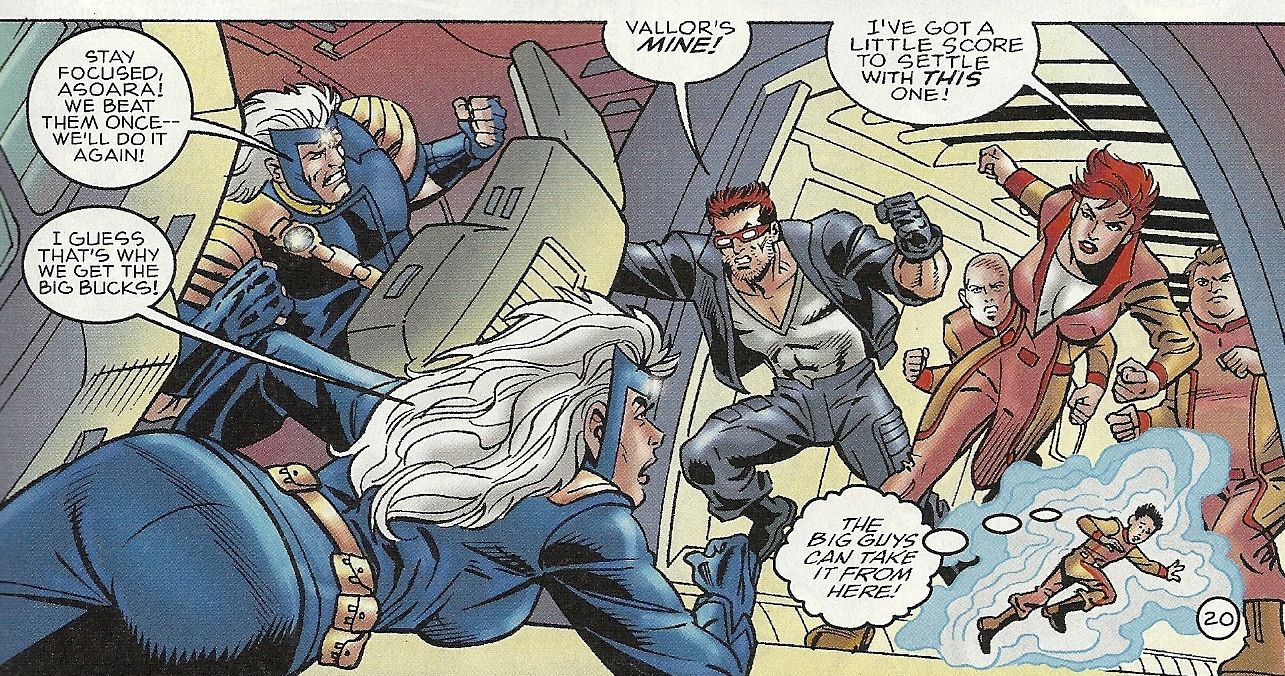

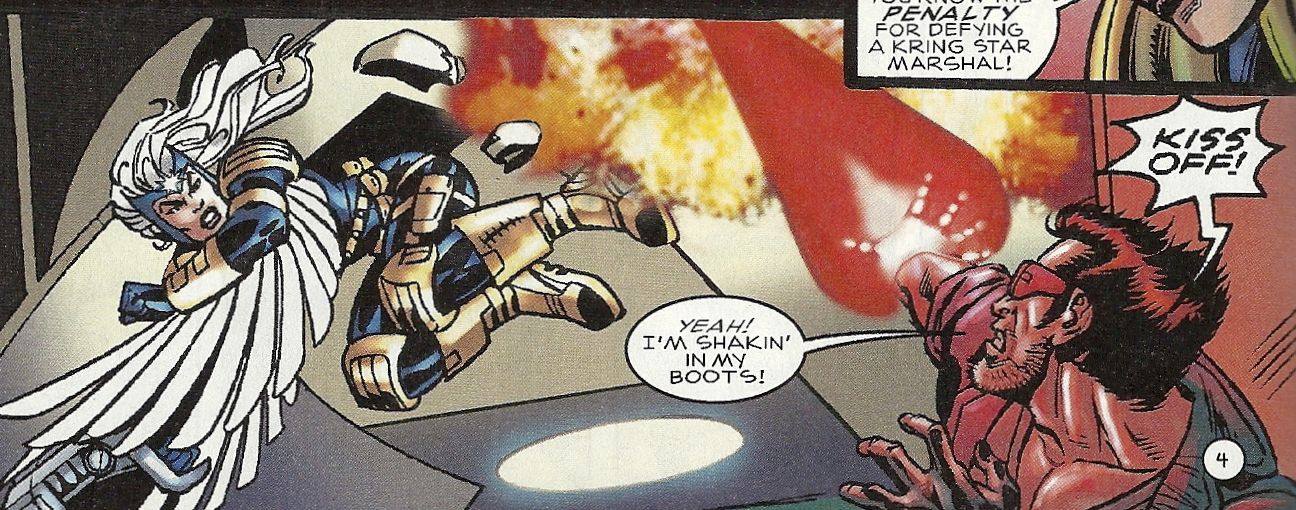

This doesn’t sit well with a pair of Star Marshals, strong guy Vallor and flying lady Asoara, who are outfitted in pieces of Jim Lee Era X-Men costumes. They capture Blastok and put him in the brig of their spaceship with four other captive super-powered bad guys (1, 2, 3…yeah, that’s seven).

These sequences are almost painful to read. The character design looks as if it was torn from one of those How To Draw Superheroes books for kids, and the dialogue reads like an imitation of Bronze Age Marvel Comics scripts done from memory.

On page 11, things get more interesting when the other story thread is introduced: Back on Earth, Stan Lee walks into the headquarters of Archie Comics, intent on selling them some Betty and Veronica stories.

But Archie Comics CEO Jon Goldwater isn’t interested in his “Betty and Veronica in the Mosh Pit of Doom,” and wants some Stan Lee superheroes. But Lee is burned out on them: “Jon, I’ve come up with so many superheroes from A-Bomb to ZZZXX. I don’t have another one in me!”

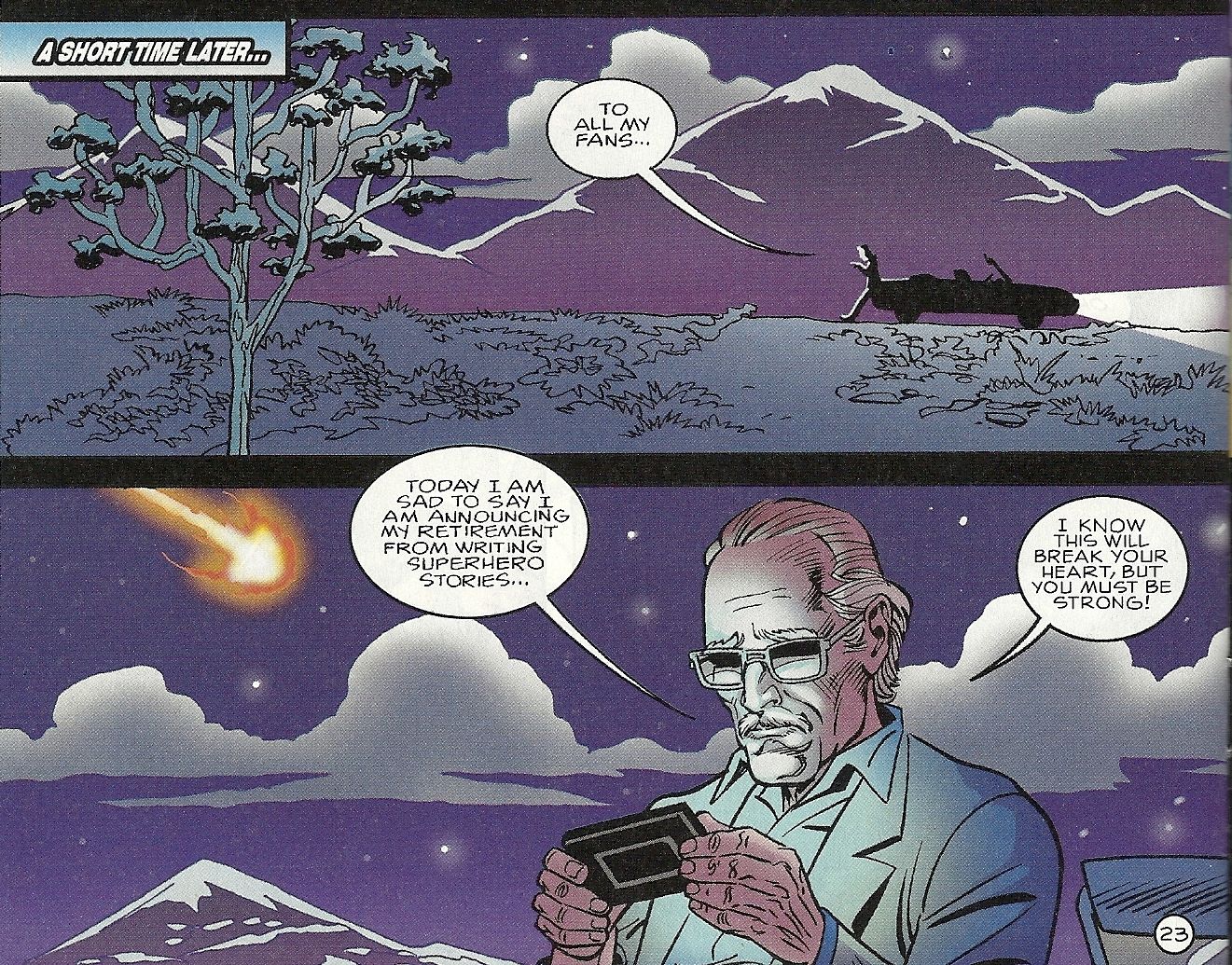

He stares dramatically out the window and announces that he’s going out to the desert to clear his head, and decides if he even wants to do another superhero book.

He’s in the desert tweeting his retirement from superheroes when the ship containing those seven superheroes crash-lands in the distance, and suddenly the book gets interesting just as the first issue ends.

This isn’t just a creatively bankrupt tale of generic super-people for unfortunate children who don’t have access to the many better all-ages comics after all? It’s actually going to be the story of Stan Lee encountering a conflict-ridden group of alien superheroes and, one imagines, coaching them into becoming a superhero team?

That has potential.

Lee and Lee’s floating head both refer to this as the comic book equivalent of reality television, “reality comics,” which is sort of silly.

The actual equivalent would be having a comics creative team follow around some attractive, privileged rich kids or colorful middle-aged men with dangerous jobs and make comics about them, which would be…interesting, I suppose.

The “reality” part of equation seems to be that Stan Lee is an actual real person, but then, putting real people in comics isn’t exactly a new genre of comics. Stan Lee has been doing it himself for years.

I think it’s a fine idea for a comic book though, and one I would be interested in reading, but boy was it tough slogging through the Lee-free pages of the book. Lee is credited with the concept, and the actual writers are Tony Black and Paul Jackson (Lee gets a “with” credit under “script”). There’s a pretty good chance their script is intentionally rote, that they are doing a skillful impression of the sort of tripe a junior high kid might write in a spiral ring notebook on the bus ride home while fantasizing about growing up to be Geoff Johns or whoever, but bad on purpose remains bad, particularly if delivered with so little wit or evident agenda.

The art comes from pencil artist Alex Saviuk and inker Bob Smith, and while their fundamentals are fine, the work is as generic as the writing. As I said, the character designs are supremely uninspired, and the costumes look like they were cobbled together with items from the wardrobes of 70s and 90s Big Two superheroes.

The production values are also remarkably poor, especially considering the book has the names “Stan Lee” and “Archie” attached. On certain pages, the fold between pages seems to eat up the edges of certain panels, and digital coloring effects are used to apparently suggest the focus of a movie camera, but more often suggest a mistake in the production process or a bad transfer somewhere. Additionally, some of the lettering looks pixilated and blurry.

All in all, it’s a pretty slipshod affair, which doesn’t do the book any favors, and seems to suggest the badness of the scripting and design might not be on purpose after all.

None of that should make the book any less interesting to long-term comics fans or industry observers, but I suppose to readers like us that makes it a book that one reads to observe rather than to enjoy.

Given the publisher, it’s a safe bet that it’s actually targeted at children, and I suppose the argument could be made that children won’t notice poor design or production the way adults might. But given the wealth of great all-ages comics material available now, I see little reason to expose children to Stan Lee’s Mighty 7.