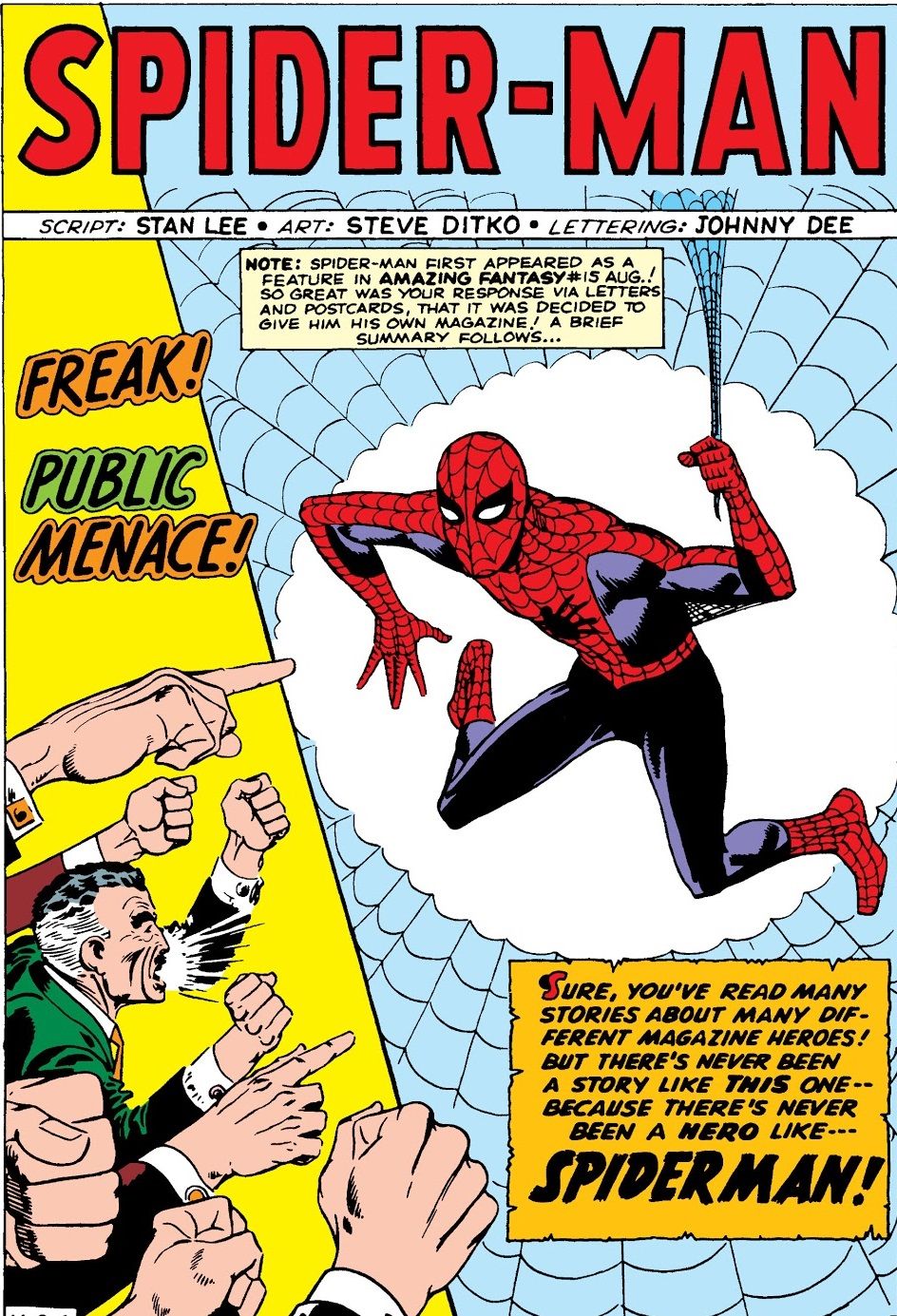

Steve Ditko passed away a little over a week ago at the age of 90. While Ditko's career was long and varied (and believe you us, we will be spotlighting all of the aspects of that career over the next few days), he clearly will always be best remembered as the co-creator of Spider-Man, one of the most popular superheroes of all-time.

It is important to note, however, that Ditko did not just create Spider-Man with editor/writer Stan Lee, but he then went on to work on the character for the next four years. Those four years helped define the character for the earliest generation of Marvel Comics fans and since that generation also helped to define Marvel Comics period, it is a very important period in comic book history.

RELATED: Steve Ditko, Comics Legend, Dead at 90

At the start of the 1960s, Steve Ditko was one of Marvel's most popular artists, but he was also a clear second to Jack Kirby, who had been one of the most popular artists in the entire industry since the early 1940s. Stan Lee leaned heavily on Jack Kirby and when Kirby was not available, he went to Ditko next. When Lee first pitched the idea of a teen hero named Spider-Man, Kirby, who had just recently launched the hit superhero series, Fantastic Four, with Lee, was the obvious choice to design the character and draw the new feature. Kirby's version of the hero, though, was very similar to a character that he and Joe Simon had pitched years earlier that Simon had then adapted into the Archie Comics superhero known as the Fly. Various reasons exist as to why Lee rejected Kirby's design (Lee has said it was too traditionally heroic looking, while others suggest that it was the similarity to an established character that did the trick), but whatever the reason, Ditko was then brought on and as he later recalled, "One of the first things I did was to work up a costume. A vital, visual part of the character. I had to know how he looked ... before I did any breakdowns. For example: A clinging power so he wouldn't have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc. ... I wasn't sure Stan would like the idea of covering the character's face but I did it because it hid an obviously boyish face. It would also add mystery to the character..."

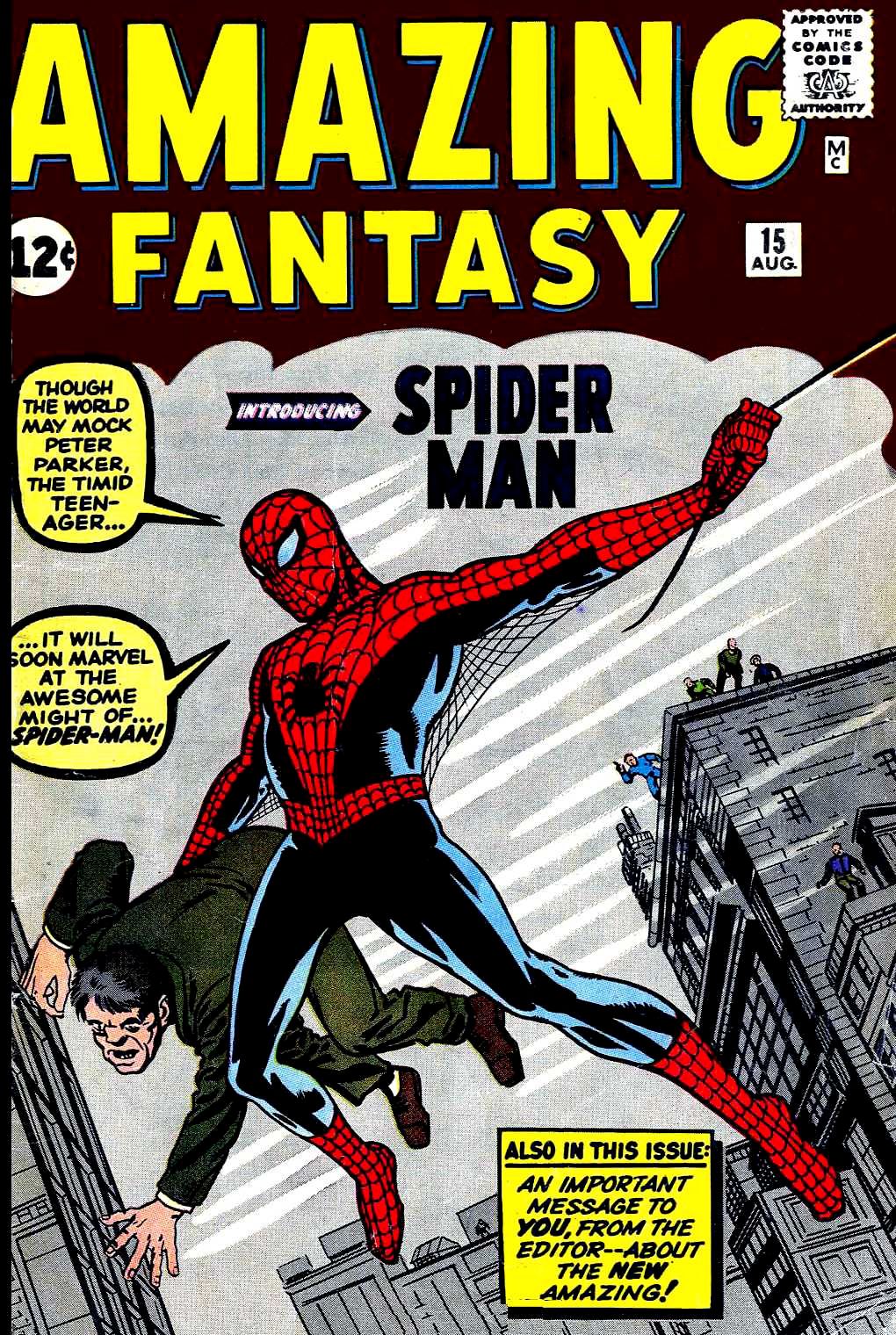

It is, indeed, one of the most striking superhero costumes of the Silver Age. Amusingly enough, however (and a testament to how Ditko was treated in relation to Jack Kirby), Lee ended up rejecting Ditko's original design for the cover of Spider-Man's debut on Amazing Fantasy #15 and had Kirby draw a different version of Ditko's design (with Ditko then inking Kirby)...

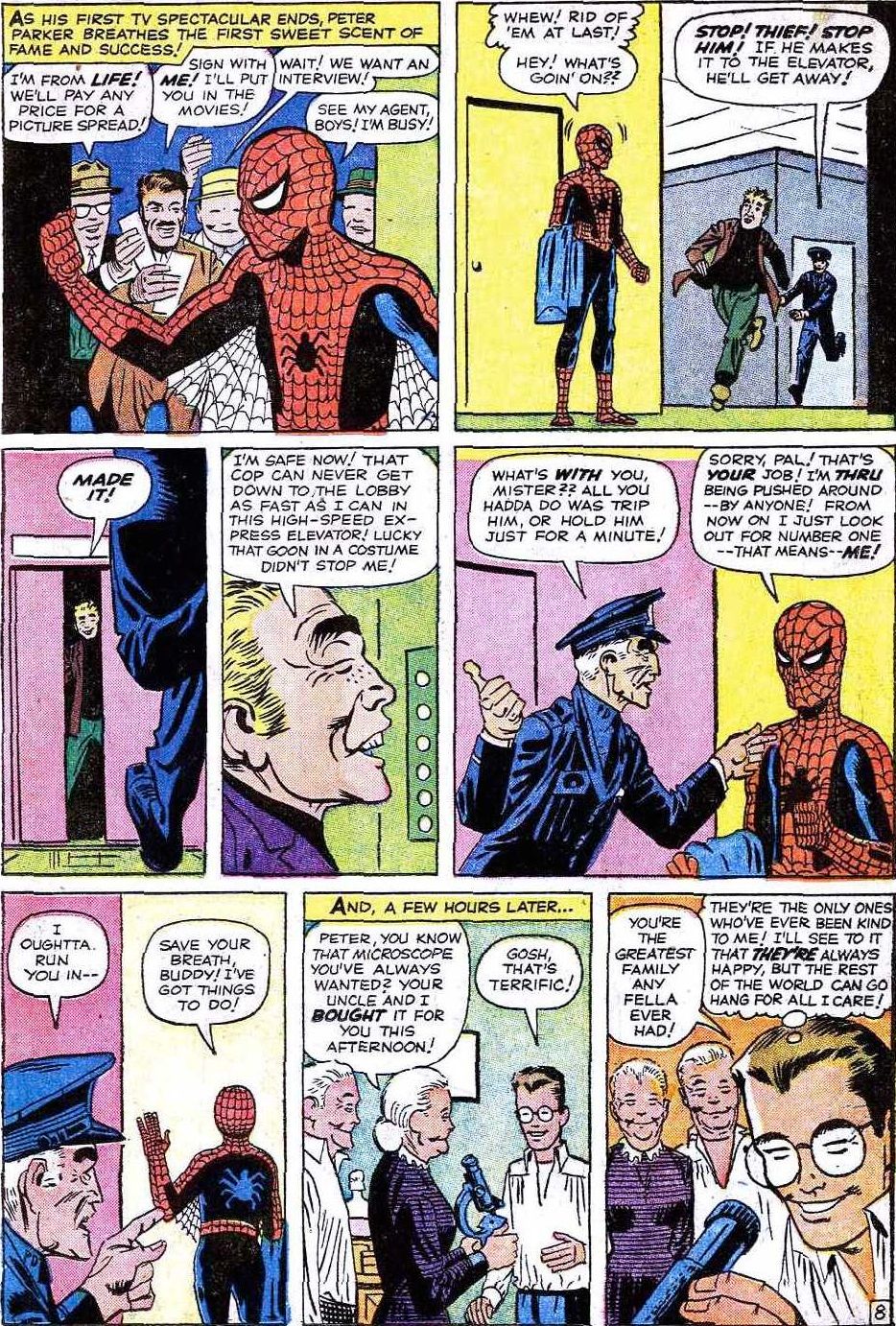

That debut issue was so unusual for its time that Lee made sure to crow on the first page of the issue that they knew how unusual the story was. Here was a teen hero, which was unusual enough for its time, but a teen whose origin begins with him being a picked on nerd who decides to use his superpowers not for crimefighting but for personal advancement. He becomes a TV celebrity and is so disinterested in his fellow man that when a criminal runs by him, he doesn't do anything to stop him...

When later he discovers that that same criminal killed his beloved Uncle Ben, then Peter Parker learned the hard way that with great power comes great responsibility...

It's one of the greatest superhero origin stories ever written. However, Lee and Ditko were not finished with making Spidey stand out.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='Threat%20Or%20Menace?']

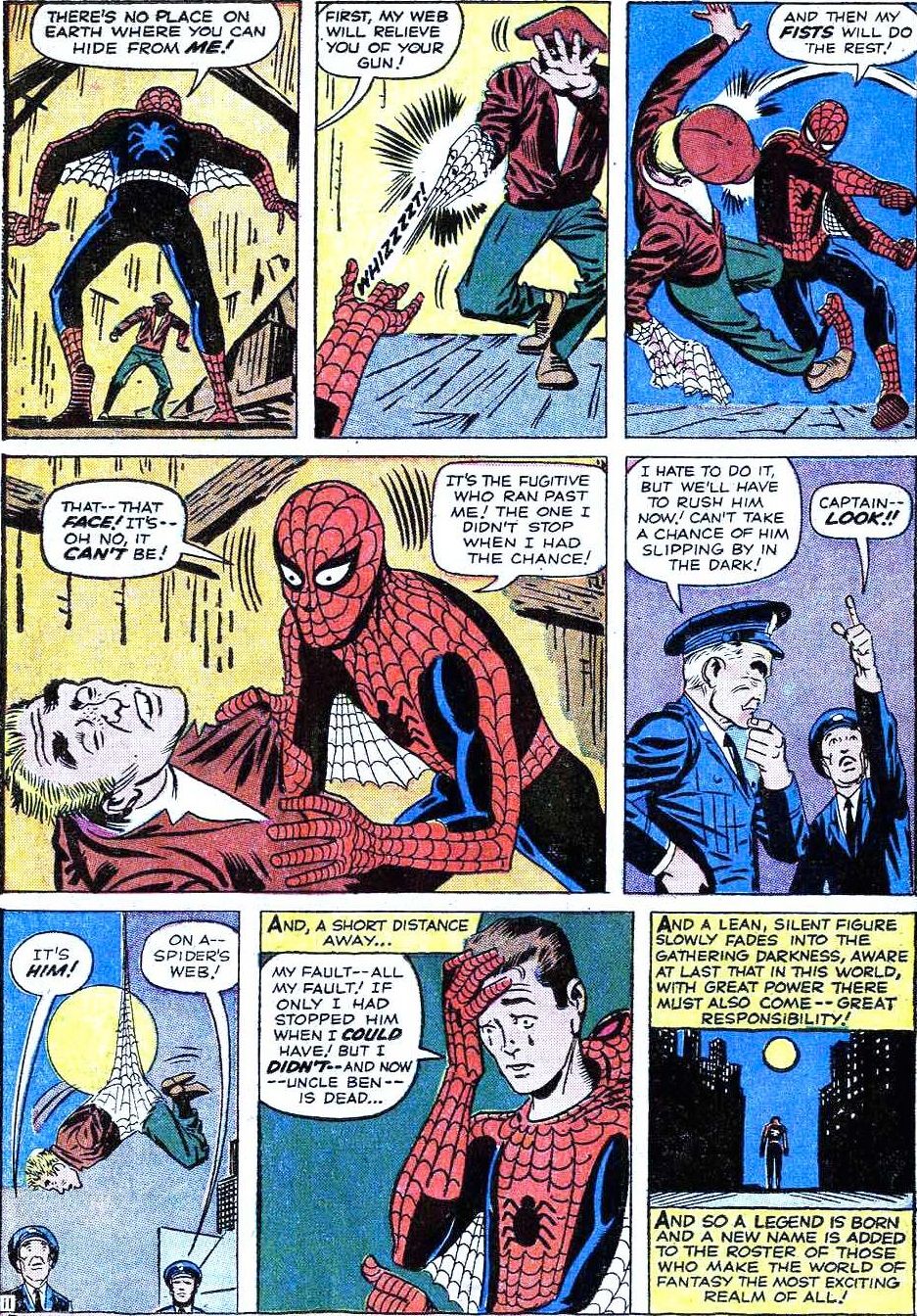

Spider-Man quickly graduated into his own title, and the very first page of the first issue showed two very important aspects of the character. One of them was devised by Lee and Ditko together and one of them was all Ditko.

You see, unlike most other superheroes, including Lee's own creation with Jack Kirby, the Fantastic Four (who Spider-Man naturally met up with in the first issue of his ongoing series, as Lee was not shy about using established Marvel heroes to help sell the newer ones, something that became a regular practice in the years since), Spider-Man was seen as a threat and/or a menace, as Daily Bugle head J. Jonah Jameson would use his newspaper to consistently turn the public against Spider-Man. So he not only had to help out people but he had to do so while everyone thinks he's a crook.

Along those lines, however, you had the way that Ditko depicted Spider-Man. He really leaned into the idea that Spider-Man might by someone who would be seen as a threat and/or menace by making Spider-Man look plain ol' weird. He did not exhibit your traditional heroic poses, but rather a hunched over, contorted pose most of the time.

RELATED: Comics Industry Pays Tribute to Steve Ditko

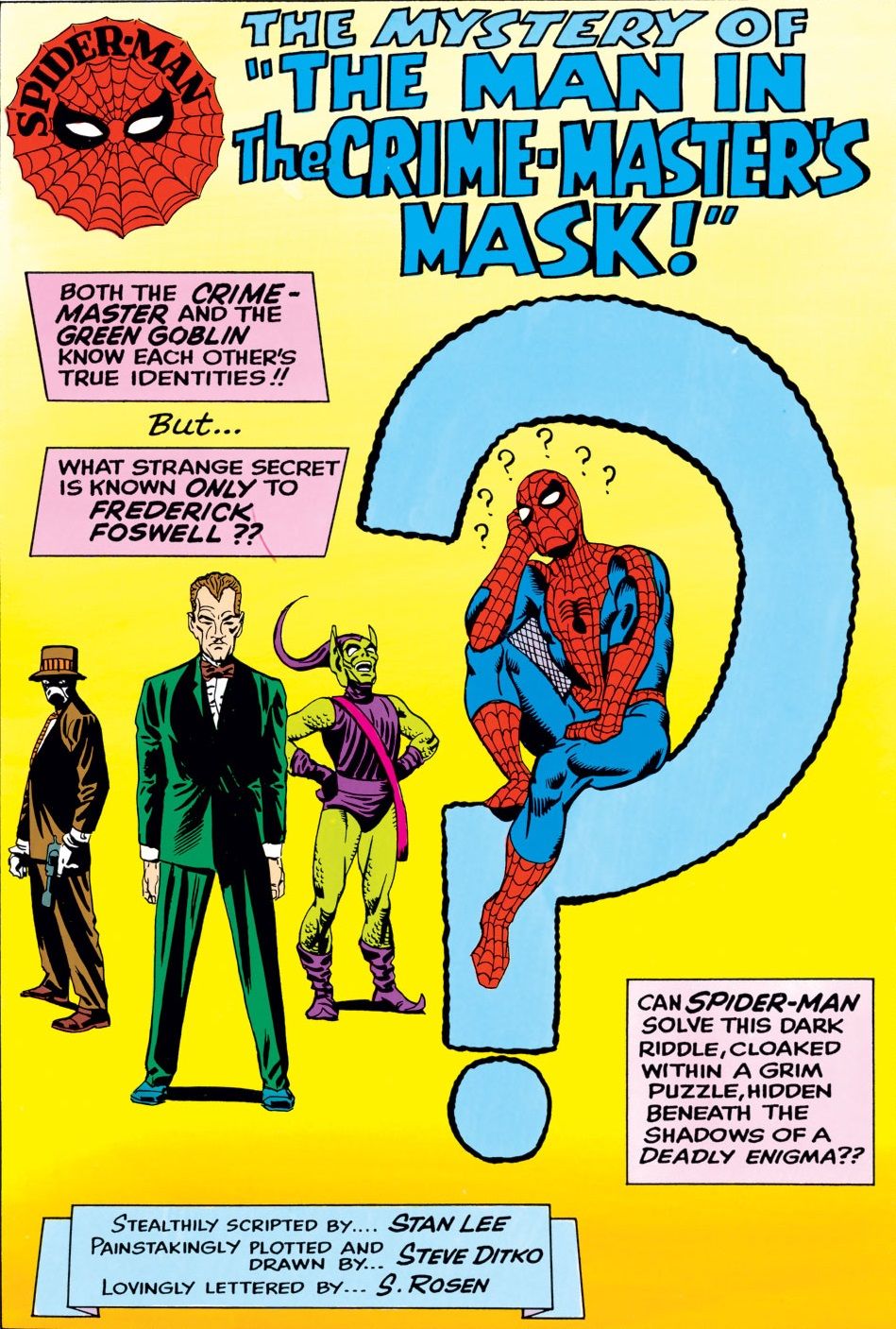

Ditko brought that design sense to Spider-Man's villains, as well, as he and Lee quickly built up one of the greatest Rogues Galleries in the history of superhero comics and almost all of them came in the first year's worth of Amazing Spider-Man issues!

In the early days of their collaboration on Amazing Spider-Man, Lee and Ditko would confer on the plot, Ditko would then go out and draw the issue and Lee would first request changes and then, once the changes were made (or Ditko successfully argued against the change), Lee would add dialogue to Ditko's pages. Lee was always fairly deferential to Ditko's views on things, but at the same time, Ditko would still have to clear things with Lee, which would often lead to re-drawn pages. For years, Lee had maintained the so-called "Marvel Method" of him coming up with a plot with the artists, them drawing that plot and then Lee adding dialogue to the finished pages. That worked a lot easier when Marvel Comics stories were short seven-page stories in anthologies. For a seven-pager, a basic plot can carry most of the pages. When comic books became full-issue stories, Lee was now expecting the artist to come up with a lot of extra plot to fill those pages.

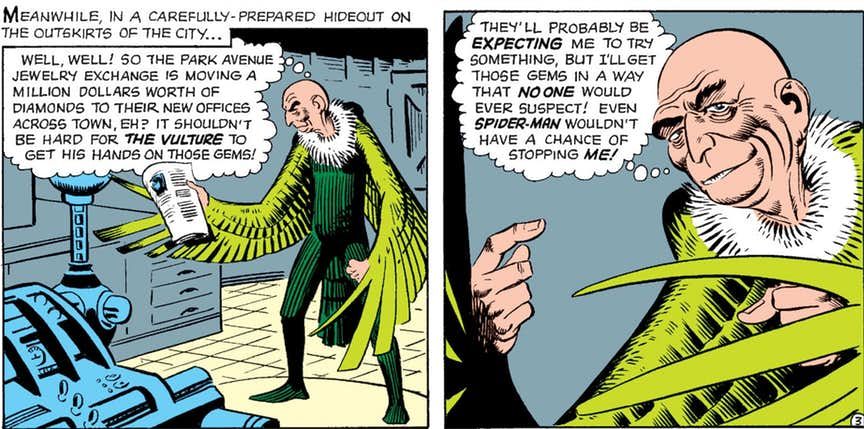

He would defer more and more to the artists that he trusted, like Ditko and, of course, Jack Kirby. Therefore, when, say, the Vulture was introduce and Lee wanted the character to look bulky, it was Ditko who said no and Lee went with Ditko. Ditko later explained his decision, “He once mentioned the movie villain, Sydney Greenstreet, as a villain model. So Stan didn’t like my thin, gaunt Vulture. An elephant’s bulk can be frightening and destructive, but it is easier to escape from than the lean, fast cheetah. The bulkier anything is, the more panel space it has to take up, thereby shrinking panel space for other characters and story panel elements.”

Page 3: [valnet-url-page page=3 paginated=0 text='Spider-Man%20Captivates%20a%20Generation']

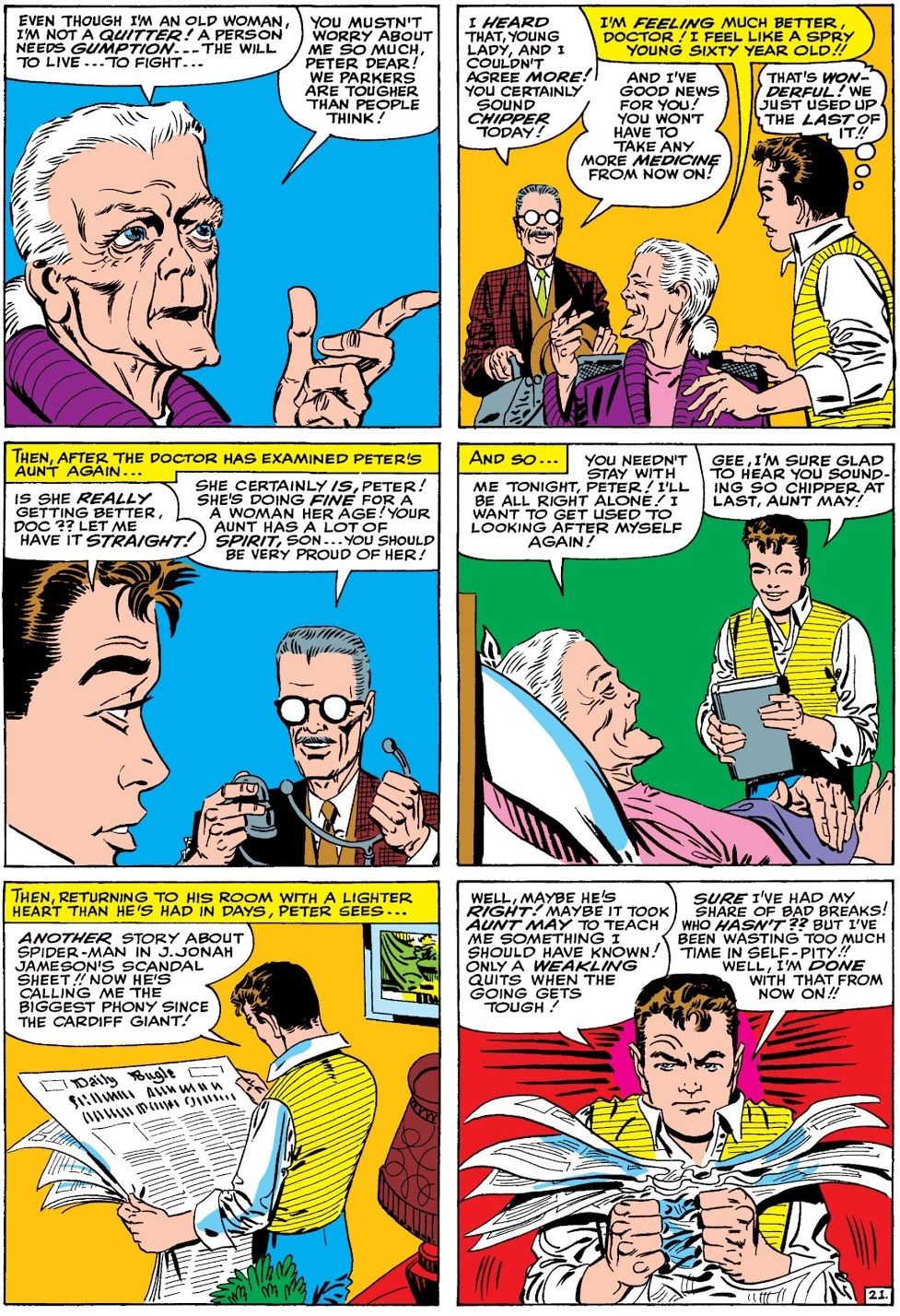

The aspect of Spider-Man that most captivated audiences at the time was that Peter Parker had so much tough luck. He was an "everyman" in how he had constant money problems and girl problems and his Aunt May (the only family he had left in the world) seemed ready to be killed at any moment from a stiff wind.

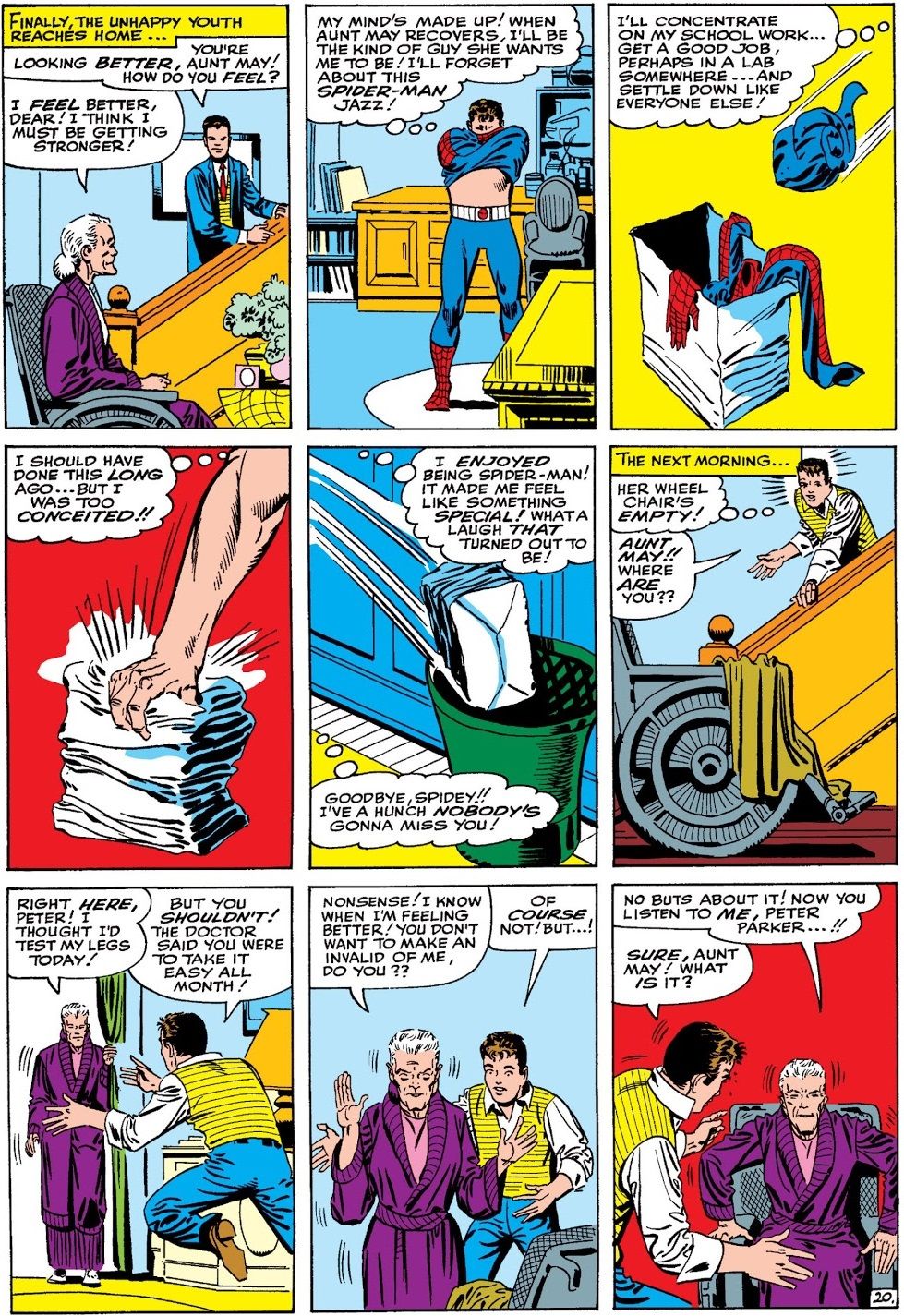

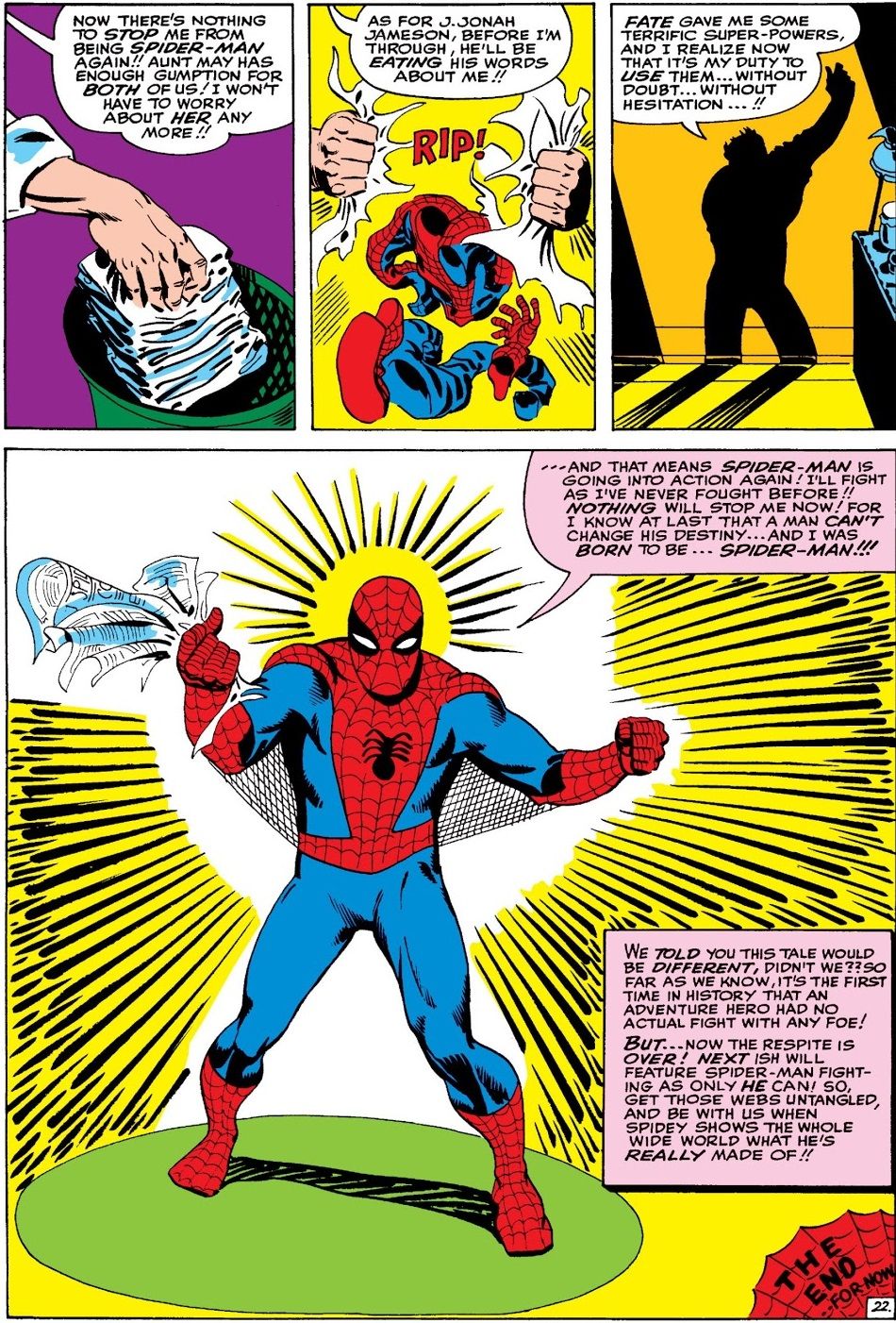

Lee and Ditko embraced this view of the series. One issue in particular stood out, Amazing Spider-Man #18, the first time that Spider-Man decided that being Spider-Man was just too much for the young teenager, before he ultimately decided to stick it out (his sense of responsibility was always strong enough to make Peter make the right choice in the end, but it is important to note that Peter was always someone who struggled with doing the right thing). The issue was an especially big deal because it showed just how popular the personal life of Spider-Man was, as Spider-Man fought no supervillains the entire issue (Sandman tries to fight him but he just runs away from the fight)...

In 1965, Esquire magazine polled college students and found that Spider-Man was just as popular to them as other generational talents like Bob Dylan. One pollee brilliantly explained Spider-Man's appeal, "beset by woes, money problems, and the question of existence. In short, he is one of us."

Page 4: [valnet-url-page page=4 paginated=0 text='Ditko%20Departs%20Amazing%20Spider-Man']

Spider-Man's popularity was a bit confounding to Ditko. Here, the character was getting bigger and bigger and yet he still had to defend his choices on every story. Finally, he demanded two very notable things for the era. One, he wanted to be credited as the plotter of the series and two, he no longer wanted to have to have anything to do with Stan Lee directly. Ditko would come up with the plots for the issues by himself, send them to Marvel (with notes to let Lee know what was going on) and Lee would then add dialogue and that was that (Ditko would later claim that Lee actually suggested the whole "not speaking to each other" thing, due to their constant disagreements).

This new set-up began in Amazing Spider-Man #25, but it wasn't until the next issue that Ditko got his new credit...

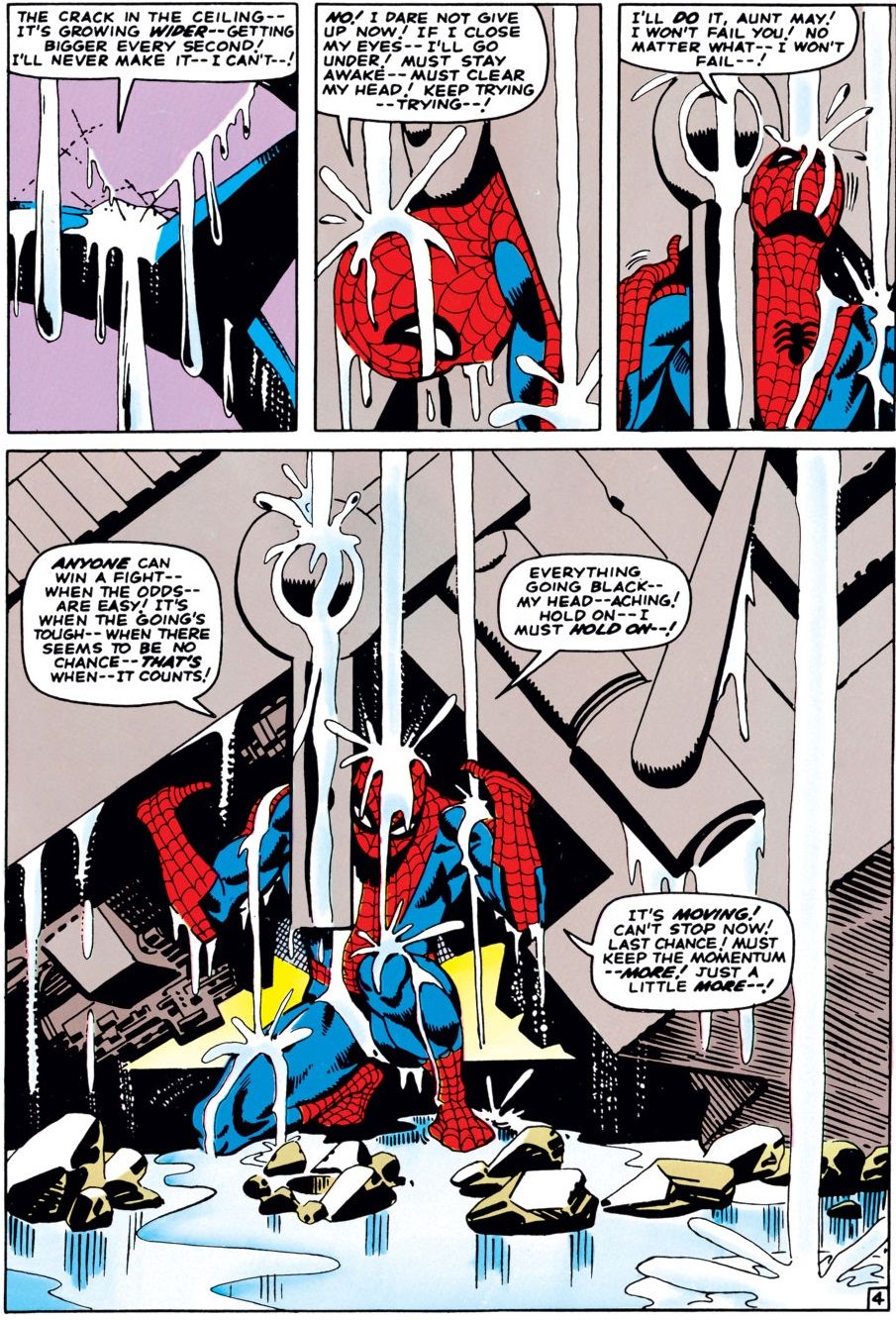

It was during this era that Ditko wrote some of the most famous Spider-Man stories of the entire Lee/Ditko run, with the most famous example being the iconic sequence in Amazing Spider-Man #33 when Spider-Man, pinned down by heavy machinery in an underground base that is slowly filling with water, a serum just feet away that he needs to save Aunt May's life, manages to lift the machinery off of his head by pushing himself beyond what he thought he could achieve....

It's rather amazing how well Lee's dialogue continued to work with Ditko's art even after the two stopped interacting with each other.

However, while Lee and Ditko no longer spoke, Marvel publisher Martin Goodman still communicated with Ditko (through intermediaries) and he kept asking Ditko to do changes (mostly stuff like, "More action!"). A key dispute here for Ditko was that he was starting to want to have Peter Parker be more defined as a hero, while Marvel wanted to continue to milk the reserved hero/"everyman" aspect of the character. Ditko specifically did not want Spider-Man to be "every man."

Spider-Man was now popular enough to get his own animated series, which simply animated Dikto's original drawings. Ditko got no extra money from this.

The whole situation was too frustrating for Ditko. A number of issues coalesced into him no longer wanting to work on his most famous creation, despite the fact that he had just recently received a pay raise (of course, a pay raise while not getting any money from the TV series based on his work is not necessarily much of an incentive).

Other creators at Marvel used to say how it was a "mystery" as to why Ditko left the series (that has led to claims that Ditko left because Stan Lee wanted to reveal that Norman Osborn was the Green Goblin. That just happened to work out, timing-wise, that Goblin was revealed the issue after Ditko left. That had nothing to do with Ditko's departure. Ditko also intended Osborn to be the Green Goblin), but in reality, it is a situation where the only "mystery" involved is precisely what was the proverbial straw that broke the proverbial camel's back.

Was it the lack of credit that Ditko received in the press over the success of a book that he was plotting and drawing by himself? Was it the lack of freedom to do what he wanted on a book that was very successful that he was plotting and drawing by himself? Was it the fact that he wasn't getting any profit participation in the adaptations of Spider-Man into other media? Was it the fact that clearly Spider-Man was going to continue to be licensed for other uses that he was not going to make any money off of while he was plotting and drawing the hit comic book that it was all based on? Any one could explain his departure, all of them together just made it an easier call.

Dikto's replacement, John Romita, would possibly make the character even more popular, as Romita made the character less weird and more commercially acceptable. Soon, Romita's version of the character would appear on all licensed Spider-Man material for the next twenty years or so. However, the foundation of the character's popularity was always built on the work of Steve Ditko.