On May 16 1997, HBO debuted “Todd McFarlane’s Spawn” at midnight to an unsuspecting audience. This was a landscape without Adult Swim, where most anime was relegated to grainy VHS bootlegs, and with a direct-to-video market dominated by Disney sequels. The market for adult-oriented animation in America was perceived as extremely limited, so HBO’s decision to launch its own animation unit for late-night viewers was far from an obvious move.

The high-end cable network's selection for its debut animated series, however, certainly had a record for success. “Spawn” was the highest-selling independent comic in history, had been optioned for a movie within the first year of its release, and the property’s line of intricately-detailed action figures had already expanded the toy market far beyond the grade school set. Hollywood was still largely ignorant of the comics industry in the 1990s, but they knew that Todd McFarlane’s undead anti-hero was worth a meeting or two.

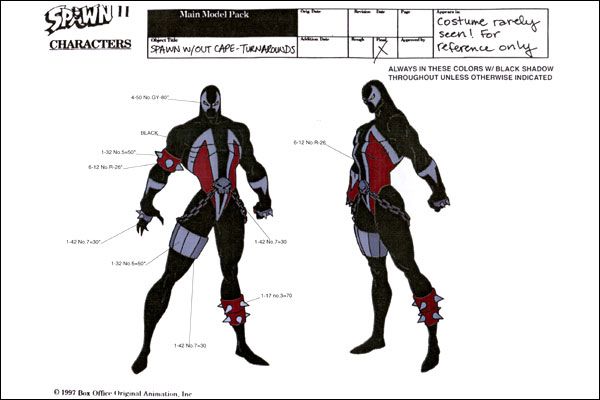

Having secured the HBO deal, McFarlane spent months investigating possible ways to bring his creation to animation. An anime look was considered early on, as was a direct adaptation of the comics, similar to MTV’s efforts with “The Maxx.” (In fact, crew members of “The Maxx” met with McFarlane, who seemed to be leaning in this direction.) “Aeon Flux” creator Peter Chung’s name was also tossed around in the early days. Ultimately, McFarlane decided to make the cartoon its own entity, one that was heavily inspired by the original comics, but with a unique storyline and visual style. Early character models featured the work of McFarlane and “Spawn” artist Greg Capullo, who streamlined the ragged details of the comic, while playing to his own cartooning strengths.

HBO's strategy for “Spawn” mirrored McFarlane's early approach to the comic book series -- hire creators with solid reputations and offer them a healthy amount of creative freedom. In comics, this meant calling Alan Moore for a fill-in issue or miniseries. In animation, it meant recruiting some big names from “Batman: The Animated Series.” (Alan Moore, by the way, was rumored to be a writer for the first season of the show, but nothing came of this.)

Within the series' opening few minutes, fans of “Batman: The Animated Series” will notice a haunting score, one that evokes certain familiar cues. This is the work of Shirley Walker, the composer who worked with Danny Elfman on the 1989 “Batman” film score, before moving to television animation, creating the most complex, poignant, and memorable scores to ever appear in the medium. Walker’s work on “Spawn” takes the gothic elements of her “Batman: The Animated Series” compositions to an even darker place. The epic heroic themes are gone, replaced with long, low notes and eerie hints of ethereal threats lurking in the distance. Some of the more “adult” elements of the series were dismissed as juvenile attempts at maturity, but the score isn’t one of them. It’s moody beyond belief, the perfect musical companion for the bleakness of the series.

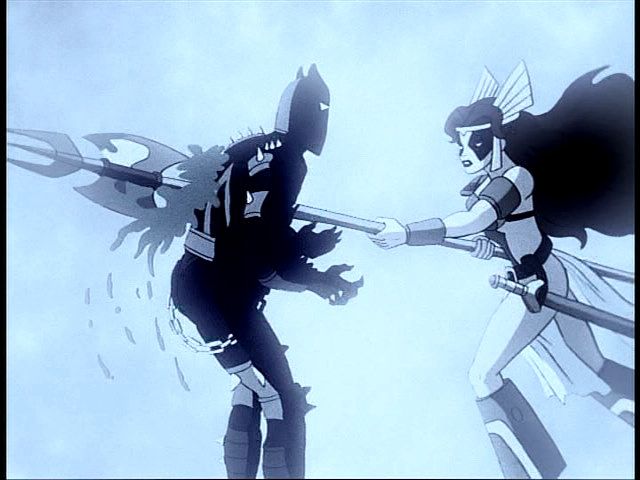

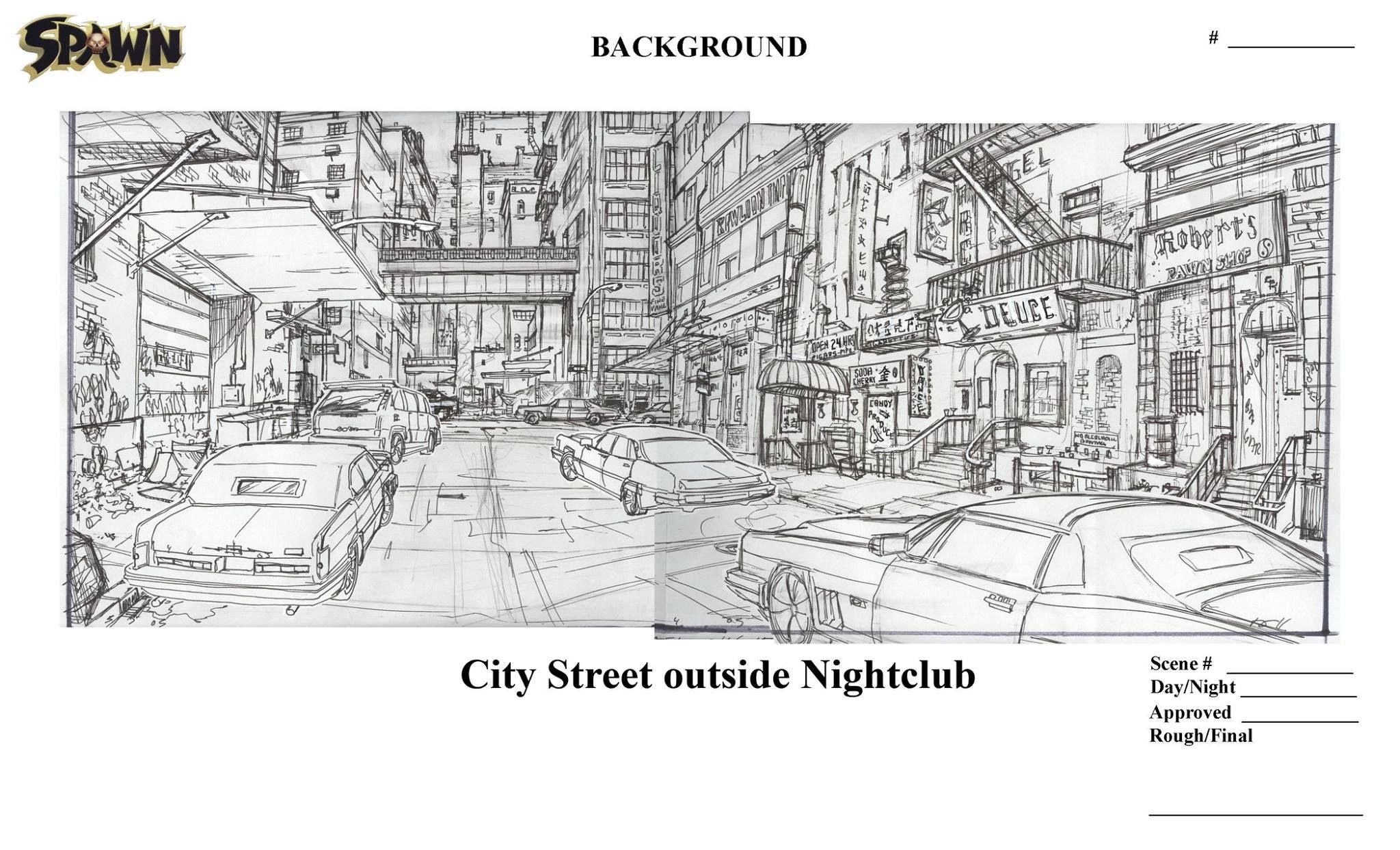

The most significant animator hired from the “Batman” crew was co-creator of the series Eric Radomski. Radomski is largely responsible for the deep shadows that bathed the world of Gotham in “Batman: The Animated Series,” making him a perfect fit for “Spawn.” Hints of Radomski’s experimentations with shadows are found in the black-on-black look of the Stacked Deck club in “Almost Got ‘Im,” and the mysterious introduction of Andrea Beaumont during the opening scenes of “Mask of the Phantasm.” “Todd McFarlane’s Spawn” takes the experimentation with darkness as far as it can go; viewers are advised to “turn off the lights” before the episodes begin, creating the illusion that the darkness of the room had merged with the sheer blackness of Radomski’s designs.

Radomski’s decision to leave Warner Brothers for the “Spawn” production had one noticeable impact on future animated DC productions. The iconic title cards that opened the original run of “Batman: The Animated Series” were the work of Eric Radomski, who’s not only a fine director and animator, but also an extremely skilled painter. While Radomski worked on “Spawn,” most of the “Batman” crew moved on to “Superman: The Animated Series”…and those distinctive title cards didn’t go with them. With the precedent of “Superman” not having title cards, and Radomski still away on “Spawn,” the revived version of the series, “The New Batman Adventures” carried on without the paintings.

Other creators hired to give “Spawn” a characteristic look included Steve Oliff, the renowned colorist responsible for the earlier years of the “Spawn” comic. Unfortunately, Oliff has only a “color consultant” credit on the first season, and it often seems this color design is not his work. Much of Oliff’s reputation came from his work in the new field of digital colors, a technique that wasn’t translating well to animation in this era. The colors in “Spawn” appear to be hand-painted cels, and the early color design is annoyingly inconsistent. Some scenes, like Spawn’s visit to his own grave, are beautifully executed, with dark, moody tones. Others, like most of the domestic scenes, suffer from an utterly bizarre pastel color scheme. The interiors of most buildings, for example, have an unattractive hue that Oliff likely would’ve never chosen for the comic. What the series does get right, consistently, is the crimson color of Spawn’s cape, and the unearthly green of his eyes. (Most likely a post-production digital effect. Notice that sometimes the green in Spawn’s eyes will blank out for a few seconds.)

The debut season of “Spawn,” which McFarlane acknowledges on the DVD release was a “learning experience,” attempts to adapt the first dozen or so issues of the comic book, using the major villains and plot points from McFarlane's original work and melding them together into one cohesive storyline. This was the work of television writer Alan McElroy, who's gone on to write various horror movies, and playing the other side of the field, the Christian-themed film series “Left Behind.” Every episode of “Spawn” features an introduction from Todd McFarlane himself, in the style of Rod Serling, discussing the stories’ themes. In the initial run, Todd's dressed like a mafia hitman, inking what appears to be an actual page of the “Spawn” comic. In later seasons, McFarlane appears in rather ridiculous sets, interacting with allegedly mystical props while philosophizing on the subject of the episode. As revealed on the DVD set, the director of the Season One intros was Doug Liman, who went on to direct blockbusters like “Mr. & Mrs. Smith” and “The Bourne Identity.”

Alan McElroy's impact on the direction of the “Spawn” franchise isn't slight. The concept of Spawn leaning on the enigmatic Cogliostro character for guidance was apparently McElroy's, and his penchant for adding conspiracy to the world of the anti-hero soon made its way into the comics. Although the “Spawn” comic was often mocked for its needlessly opaque handling of various conspiracies, Season One of the animated series actually crafts an engaging web of intrigue, pulling together Spawn's widow (now a lawyer, because the comics never provided her with a specific job), his former boss within the CIA, a child killer, an innocent patsy, a Senator with a secret, and an alley littered with the bodies of Washington reporters and mob hitmen. There's a steady flow to the initial run of episodes, which is only interrupted by a pointless detour involving Spawn's nemesis Violator disguising himself as a priest and kidnapping a mute child.

As the initial season sets into place the various pieces of the conspiracy, the story of Al Simmons -- government assassin killed by his agency and sent back to Earth as a part of a crooked deal with a devil -- is presented with honest sensitivity. The series does occasionally describe Spawn's predicament (his wife is now married to his best friend) in a crude manner, but the loneliness of the protagonist feels genuine in most of the episodes. Not only does Shirley Walker's score help to convey this feeling, but Keith David's portrayal of Al Simmons/Spawn also captures the character perfectly. David is rightfully viewed as one of the greatest voice-over artists working today. Whatever the script calls for -- Spawn threatening an intruder in his alley, delivering a monologue about his past life, or quietly interacting with his wife's young daughter -- David delivers.

Season One series also deserves credit for fleshing out the characters of Terry and Wanda, the former best friend and spouse of Al Simmons. They do feel like a married couple that genuinely loves one another, and their inclusion into the larger conspiracy storyline actually seems organic. Spawn's supporting cast of homeless vagrants also have a better showing here, when compared to their portrayal in the comic series. Here, no one looks up to Spawn as some sort of king; he's a strange presence in their home, and while some are welcoming, others just want him out.

While the opening episodes likely surprised anyone expecting thin plots and poorly defined characters, the visuals do suffer throughout the original run. The best-looking episode from this year is the season premiere, and what follows is a succession of inconsistent designs and animation. The look of this season is often reminiscent of syndicated action cartoons from '80s, with only occasional hints of the “Spawn” comic. There's a sense that the overseas animation studio is dropping many of the detail lines, and often the coloring choices are distractingly ugly. (Eric Radomski has revealed that one of the overseas studios subcontracted to produce the animation just wasn't up for the job, which is one reason why he was hired to aid the troubled production.) McFarlane has explained that he wasn't happy with the look of the first run of episodes, and experimented with the editing in order to distract from the visuals he disliked. The look of Spawn, in full costume, is usually great, but many of the peripheral characters just seem to be poorly designed. The overall look of the series is inconsistent, and the actual animation is lifeless at times.

McFarlane's issues with Season One's visuals were resolved quickly in Season Two, after legendary animation studio Madhouse was hired to take over the series (with help from D. R. Movie, another respected firm). “Spawn” now has a cohesive look, one with an obvious anime influence, but also with a playful sense of cartooning that's similar to what McFarlane and Capullo accomplished in the monthly “Spawn” comic. The cartoon still doesn't resemble the comic series, except for specific images of Spawn himself, but it follows the basic aesthetic of the comic's early years. The gruesomeness of Spawn's story is counterbalanced with lighthearted cartoon images of silly characters, all somehow a part of a coherent universe, and the animation is remarkably smooth in most scenes.

For reasons unknown, Alan McElroy didn't return for a second season, leaving “Spawn” without a strong authorial voice in its second year. The focus for Season Two would move away from an interconnected storyline, instead attempting one-shot stories with a bit of “soap opera,” as McFarlane put it, thrown in.

HBO was reportedly not pleased with the scripts for Season Two, and made the unusual decision to order re-writes...after the animation had already been turned in. This was accomplished by redubbing lines of dialogue over the animation, which was now so intensely covered in shadows, the original script was often obliterated. Other scenes covered the rewrites by recycling the same bits of animation as a monologue carried on, or by dubbing in new dialogue that clearly didn’t match the lip sync. McFarlane called in two writers he'd become acquainted with, John Leekley and Rebekah Bradford, to reconceive the second season of the show. Leekley had a background in made-for-TV movies, but not animation, creating a strange tone for this season.

Season Two attempts to tell the story of Spawn’s former best friend, Terry Fitzgerald, on the run from another evil government conspiracy as its ongoing subplot, while the main stories usually have Spawn facing random acts of evil. The plots aren’t nearly as coherent as the first season’s, and more than once the “suspense” in an episode turns to boredom, but the producers do deserve credit for maintaining a focus on the series’ supporting characters. Also, the mood is true to the spirit of “Spawn,” often out-creeping the first season. More importantly, the visuals from Madhouse and D. R. Movie are spectacular. Season Two is, by far, the most visually appealing season of the show.

If Season One featured a surprisingly mature storyline, but suffered from unreliable animation, and Season Two greatly improved the visuals while muddling the story a bit, “Spawn” Season Three was certainly going to work out those kinks and surpass those previous efforts…right? Sadly, the third season of the series is widely viewed as the weakest of the show’s run. By 1999, HBO had given up its animation division, leaving “Spawn” as its sole animated programming, and apparently not much of a priority. Eric Radomski departed the production before Season Three, leaving Frank Paur to take his place. Madhouse also dropped out of the third season, and it's clear by the end of the season premiere that show isn't going to match the previous season's visuals.

While Alan McElroy’s scripts were often enough to keep the first season interesting, compensating for the inconsistent animation, the stories in Season Three can’t stand on their own. Admittedly, Season Two did lean too heavily on slow-moving scenes that favored suspense over plot advancement, but the third season leaps to a strange new sense of pacing. Supernatural elements now pop up in every episode, and while this might be welcome to anyone who’s complained that Spawn rarely does anything, their inclusion radically disrupts the tenor of the series. Often, Spawn is still left as an ineffective spectator in the series’ events, anyway.

Season Three opens with the mysterious Cogliostro blurting out a ludicrous origin story, then has behind-the-scenes bureaucratic villain Jason Wynn suddenly becoming obsessed with the numinous properties of Genghis Khan’s mask, a nonsensical story involving vampires, and the arrival of an angel to face Spawn…one that isn’t Angela. Even though the fan-favorite character made a cameo appearance in Season One, legal issues prevented Angela’s return, so a forgettable replacement was brought in. Another legal issue would arise from the HBO series, haunting McFarlane for months -- hockey player Tony Twist had no clue McFarlane had been using his name for a mobster villain, until the character made his national television debut on the cartoon.

The major event of Season Three has Spawn discovering that his cloak possesses shapeshifting properties (a divergence from the comics), and then disguising himself as his widow’s current husband. Spawn makes love to his wife for the last time, a scene that would rightfully generate a severe backlash today, and inadvertently creates a seed that will fulfill an Armageddon prophecy. And, with that cliffhanger, “Todd McFarlane’s Spawn” disappeared from the airwaves.

The finale season of “Spawn” is a sad farewell to a series that eradicated the boundaries of television animation, and often presented a superior interpretation of McFarlane’s creation. Spawn’s sense of isolation, the despondency of his world, and the sheer visual appeal of his design haven’t always lived up to their potential, but the closest they ever came was during the HBO years. The show’s Emmy for Outstanding Animation Program was well deserved.

For fans willing to forgive the third season, all hope isn’t lost for Spawn’s animated return. Ten years ago, McFarlane announced “Spawn: The Animation,” featuring the work of Film Roman Animation, the voice talents of Mark Hamill, Clancy Brown, and most importantly, the return of Keith David as Spawn. Legal issues delayed its release, but the rights have reverted to Todd McFarlane. As of 2009, McFarlane was telling interviewers that he was “85% done” with the project, with the voice acting already recorded and most of the animation completed.

So…where is it? McFarlane has consistently responded that he’s going to finish the project, and that it might even make its way to HBO, but there’s no word on specifics. 2017 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the “Spawn” franchise, and specifically the twentieth anniversary of the animated series. The Spawn action figures have recently made a comeback, Todd McFarlane is making his presence known on social media, and the monthly “Spawn” comic series is receiving more attention lately. 2017 would seem to be the perfect year to finish that final fifteen percent and give fans “Spawn: The Animation.” The current media environment has numerous outlets for the series, and to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of one of the projects that opened those doors, perhaps this should be the year to herald Spawn's animated return.