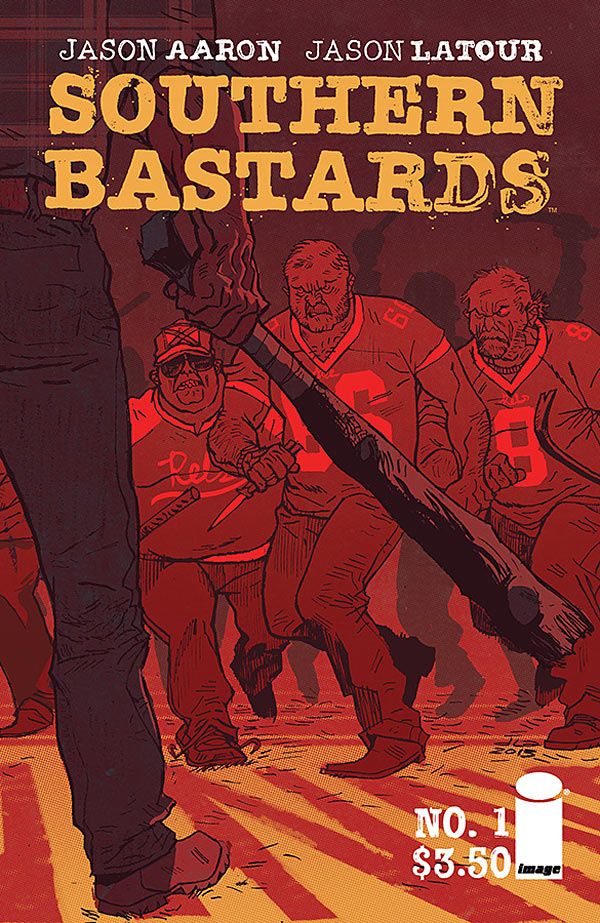

If there's one thing I've learned writing the previous 96 IN YOUR FACE JAM entries, it's that I cannot predict what's going to trigger a column from me. The type of emotion that begs for this column's catharsis comes from the most unexpected places. I've been on a super hero kick these past few, um, forevers, and I could easily write about the X-Men every single week -- I just know I have a really powerful essay about Warpath's character arc lurking inside me somewhere. But that's not what I'm writing about this week, because I finally got around to reading Image's "Southern Bastards" #1 by Jason Aaron and Jason Latour a few days ago, and it's all I can think about right now.

I'm from the South, specifically Tennessee. I was born in Nashville, spent my childhood in Hendersonville, and spent middle school through college in Murfreesboro. I've only ever lived in two states, Tennessee and New York, and sometimes I wonder how I survived moving straight to New York City following 21 years spent in the Volunteer State. I moved here because of an internship, and I stayed because I fell in love with this city. For some reason, Nashville terrified me while NYC welcomed me; maybe it was because Manhattan's grid system felt comforting to the guy that always got lost trying to navigate Nashville's nonsensical streets.

Slowly, being a Southerner in New York City started to increase what little pride I previously had for my home region. I've become much more interested in Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton as a New Yorker than I ever did as a Tennessean, and I've found myself wanting to wear t-shirts -- t-shirts -- emblazoned with my college, home town, and/or home state. I watch the ABC primetime soap opera "Nashville" for two reasons: Connie Britton, and the fact that -- since the show is filmed in its namesake -- it looks like home. I think my Southern pride also bloomed because it makes me feel a little bit unique up here. I mean, most of this "uniqueness" comes from me being incredibly unfamiliar with things that the majority of my non-Southern friends seem to innately understand. Before moving, everything I knew about Judaism and Catholicism I learned from "Seinfeld" and "Sister Act." No one in Tennessee ever "got brunch," at least not in my social circles. Yeah, there have been more than a few times that I have turned my ignorance into regional pride just to make myself feel better.

I've kept Tennessee's positive aspects close to me. I'm proud of where I'm from because of little things like the humming sound that summer makes, or abstract things like just how relaxed the air feels compared to my current borough. I miss riding jet skis down the Tennessee River and eating at kitschy chain restaurants no one up here has heard of (Logan's Roadhouse). I miss my friends, I miss my family. A lot of this affection is subconscious; my friends have told me countless times that my accent gets thicker the farther I travel from New York.

"Southern Bastards" took a big ol' stick to my memories, and left them bruised.

It didn't wreck my Southern pride, but it's forced me to reckon with its dark side. The comic depicts Earl Tubb's return to his hometown in Craw County, Alabama after decades spent living anywhere else, a visit instigated by his need to tie up a few loose ends so he can permanently escape the South. He returns to find Craw County much like he left it, except now the town doesn't have his sheriff father desperately struggling to keep it in line. Every lowlife has fallen under the sway of the no-good Coach Boss, the hard-nosed high school football coach that's got the new sheriff tucked in the pocket of his tight coach's shorts. Earl's gotta make things right, even though he wants nothing more than to head north of the Mason-Dixon.

Jason Latour's art rattled cages containing memories I've long let rest. The evangelical roadside signs, the deserted and antiquated town square complete with Civil War statue, a hoppin' BBQ joint -- these sights were all part of the first two decades of my life, but they've never been a part of a comic book that I've held in my hands. Earl's childhood home reminds me so much of my great grandmother's old house, which served as the backdrop for family football games I've watched on Super 8. And the fervor on display at the Runnin' Rebels football game Earl begrudgingly attends in the second issue matches what I witnessed on my own high school's bleachers every Friday night during my time in marching band. But those are the good memories.

I'm not going to pretend I come from anything other than a firmly middle-class family nestled within the safety of mall-filled, Southern suburbia. All of my friends were nerds, misfits, mods, Democrats, or a mix of some/all of the above. I tell this to people up North to try and knock the notion that everyone from the South is a Tea Partyin' country bumpkin. But the version of the South I take pride in -- Loretta, the river, the summers, my loved ones -- has a flip side containing every bad thing depicted in "Southern Bastards," and I can't forget that. Every face in this book belongs to someone I'd forgotten existed. I've seen Zubaz-wearing rednecks shouting in gas station parking lots, and I've seen meth heads with eyes just like the ones Latour colored. Malicious busybodies have hurt my family in the past, even if they've told them to buzz off, just like Earl tells Dusty when the burnout sidles up to him in the BBQ joint. The claustrophobic sense of dread Aaron and Latour have conjured onto the page is as Southern as a Goo Goo Cluster.

As much as I love going home, there's a dangerous side of the South -- more dangerous than anything I have ever felt anywhere else. "Southern Bastards" made me feel exactly how I feel every time my boyfriend and I drive from Queens to my hometown. Every gas station we stop at is populated by Southern bastards, and I hate having to cross my fingers, hoping that every one of them thinks me and him are just friends. I know the discriminatory laws my home state has passed or tried to pass, and I know how people in my life talked before I told them about my homosexuality. I've heard the inflammatory messages preachers deliver on Sunday mornings, somehow working the gay threat into every sermon -- I know because I sweated through one the morning after I kissed a boy for the first time. I love parts of the South, and "Southern Bastards" reminded me that parts of the South don't love me.

But as powerful as the first issue was, the letters Aaron and Latour included are what really hit me. Both of their contradicting reactions to the South -- Aaron's moved and plans to never return, while Latour defiantly returned to his home in the Carolinas -- spoke to me and articulated feelings I haven't been able to articulate myself; I've spent 1,218 words now trying to do what both Aaron and Latour accomplished in one page. But both of them address the South that I've been ashamed of, the one that makes me fear for my safety and the one that I have kept buried underneath Dolly Parton GIFs on Tumblr. I related to them in a way I have never related to comic book creators before, all over a comic book that hits closer to home than anything I've ever read.

So this is it, my declaration to the bastards of the South. The South is more than just a bunch of ignorant rednecks with Confederate flag license plates. I'm a liberal, feminist, gay, mustached, rock and roll loving comedian who makes a living as a comic book journalist -- and I'm a damn Southerner too. Every article I've written, from the progressive, to the downright silly, to the progressively downright silly all come from a Tennessean, born and bred. Just like the closing letters in the first issue state, we can't let them define the South for us. I'm glad Aaron and Latour are leading the charge.

Brett White is a comedian living in New York City. He co-hosts the podcast Matt & Brett Love Comics and is a writer for the comedy podcast Left Handed Radio. His opinions can be consumed in bite-sized morsels on Twitter (@brettwhite).