Papercutz has been releasing its translated versions of Pierre “Peyo” Culliford’s classic Smurfs comics since 2010, and it’s the sort of publishing project that is so welcome that one doesn’t like to complain too loudly about some of the less important choices made in the republication.

I’ve only ever had two real complaints about Papercutz’s presentation of the comics, of which the publisher has released 16 slim volumes.

First, there was their size: At 9 inches tall and 6-and-a-half inches wide, the four- or five-tiered page layouts could result in Smurf-sized panels. The comics were never illegible or even all that hard to read, but with an artist of Peyo’s caliber, I and many other readers would have preferred to be able to see the pages and panels bigger, to better appreciate their construction and line work (this is the complaint I’ve heard most often regarding the new Smurfs line).

Second, there’s the lettering, particularly regarding sound effects: It had a tendency to look more cut-and-pasted than organic, drawing unwanted attention to itself and away from the story being told.

Papercutz just released the first new volume in a new Peyo series that should address those exact concerns, however: The Smurfs Anthology Vol. 1 is a hardcover 11-and-a-quarter inches high and 8-and-three-quarter inches wide.

Like the little $6 trades, it’s still a pretty outstanding value at just $20 for a 200-page hardcover with a half-dozen long stories, including the Smurfs’ rough-looking first appearance and probably the two most talked-about Smurfs stories of all time, “The Smurf King” and “The Purple Smurfs” (formerly Les Schtroumpfs Noirs, but more on that later).

But it has the size and durability of a for-grownups publishing project, and the bigger size eliminates the main complaint of the previous publications. These panels and pages are easier to see, easier to read and, most importantly, easier to scrutinize.

The increased size also helps the lettering, I think, as the presentation allows the sound effects to breathe … or at least gives the impression that is indeed the case.

For this initiative, Papercutz is putting the stories back in the order they first appeared, and including any and all Johan and Peewit tales in which the Smurfs appeared, although in this volume, for example, “The Magic Flute,” one such Johan and Peewit story, is the final story in the collection, after the Smurfs stories. (So I guess the plan is to publish the Smurfs albums in order, followed by a Johan and Peewit story guest-starring the Smurfs as a chaser?)

This volume also includes a pair of prose introductions by “Smurfologist” Matt. Murray (not a typo; there’s a period at the end of the name “Matt” for some reason I don’t understand), to “The Purple Smurfs” and “The Smurf King,” furthering this book’s for-grownups bona fides.

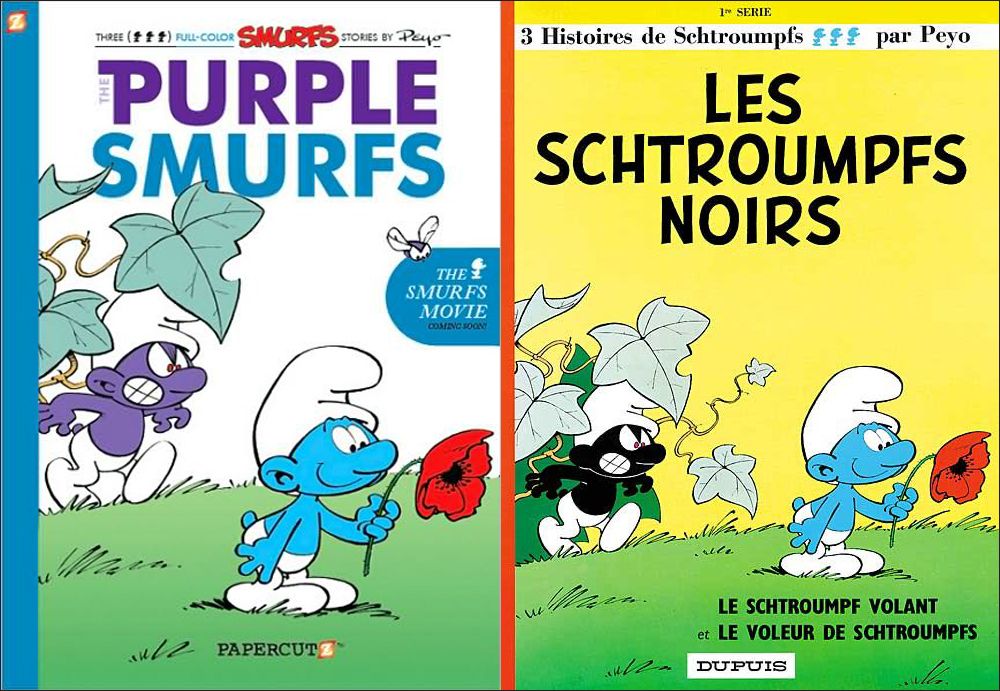

But that brings up a new problem, and perhaps another complaint that North American grown-ups might have with Papercutz’s handling of these comics: The Purple Smurfs are, as you can see on the cover, still purple rather than black.

See, in 1959, the little blue humanoids who guest-starred in a few of Peyo’s Johan and Peewit comics, graduated to their own spinoff status, with a story titled Les Schtroumpfs Noirs, or “The Black Smurfs.”

When a fly bites a hapless Smurf on the tail, his blue skin turns black, his pupils turn red, and he grits his teeth and begins hopping around, shouting “Gnap!” over and over. Then he bites another Smurfs tail, and the same thing happens, until a zombie-apocalypse plague has struck the Smurf Village (almost a decade before Night of the Living Dead!), until Papa Smurf is the last Smurf smurfing — er, standing, desperately working on a cure in his besieged laboratory.

When American producers started adapting Smurfs stories into Saturday morning cartoons at the dawn of the 1980s, a problem with this scenario immediately became apparent: How would the new audience of children react to a storyline in which a Smurf’s skin turning black transforms them into crazy, angry, mindless biting machines …?

So the Black Smurfs became the Purple Smurfs on TV, and, when Papercutz released its translation of the comic, the Black Smurfs were Purple Smurfs, and purple they remain.

Should they still be purple though, even in this particular collection, which seems so geared toward adult aficionados of comics more so than children?

As I mentioned, this story is prefaced by an article by Murray, in which he explains the color changes and contextualizes them. Peyo’s inspiration for the infection sweeping through this medieval mushroom village was the medieval Black Plague. The book includes the original cover, on which it's clear the Black Smurfs are black Smurfs and not African-American Smurfs. I can’t imagine there existing much confusion among 21st-century adult comics readers, particularly after Murray’s preemptive preface.

There’s certainly nothing approaching the casual racism of the depictions of black and brown folks or native cultures seen in some of Osamu Tezuka’s works, or Will Eisner’s The Spirit, or Carl Barks’ Donald Duck comics, or (especially) Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse comics, all of which publishers as various and DC Comics and Fantagraphics have made available to today’s adult readers in unaltered form, despite the cringes they might induce or how hard it might make some of the stories to read for modern audiences. (I don’t shock easy, but Gottfredson’s cannibals in the “Trapped on Treasure Island” story came as quite a surprise, and made the reading of the story pretty hard to accomplish).

Each of the above featured actual caricatures and jokes based on racial and ethnic biases and stereotypes, and while there may have been discussions among today's readers as to why these images exist or how harshly we should judge the creators for producing them, we seem to have survived them all, and without even so much as the sort of fireworks that, say, Tintin in the Congo has set off in recent years.

The Black Smurfs, on the other hand, are simply the color of ink, and it would take either a deliberate misreading or skepticism of the sincerity of Murray to see them as any sort of statement on race.

I think we could have taken The Black Smurfs in this album, is what I'm saying. But, as with the smaller-sized albums, this is material I'm more thankful is here and available in this form than whether or not it's available in an ideal form.