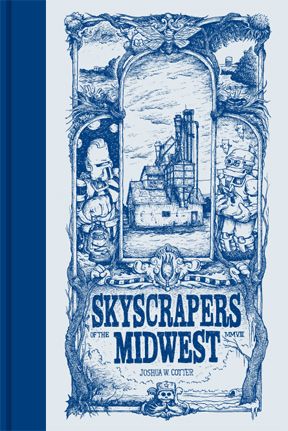

Over the years, I've skimmed through various issues of "Skyscrapers from the Midwest." I'd see the AdHouse table at a small-press show, and I'd see Josh Cotter's colorful covers, featuring weird skeleton children or robots and think that his work was something I'd really like. But then I'd flip through the contents, see some anthropomorphic cats and rural landscapes and wonder what any of it had to do with those brilliantly imaginative covers. I never cared enough to actually buy any of the issues and read them to find out. And shame on me for not supporting Josh Cotter's work, because now that I have a copy of the hardcover collection of "Skyscrapers of the Midwest," I understand exactly what Cotter was doing and recognize that this collected edition is one of the best of the year.

Don't be like me and let the anthropomorphism and dream-like narrative sequences fool you: this is no whimsical lark of a comic. This is the work of an artist with a strong voice and a unique vision of his own childhood. A childhood filled with moments of joy and pain, uncanny situations and flights of fantasy, but above all, a sense of frustration and sadness that rings all too true. This is one of the most accurate visions of childhood that I have ever seen, in any medium.

The unnamed protagonist of the story, clearly meant as an analogue for the author's own self as a child, is geeky and overweight, and Cotter quickly establishes his relationship to the world in the opening pages as he's picked last for the kickball game while playing with his toy robot. He's not even picked last, really. He's the last one not picked, and when the older boy says, "sorry, bud. Teams are even now. Uh. . . you can be captain next time," we know everything we need to know about this character and the culture he lives in. He knows he won't be captain next time, and so do we.

Instead, he retreats into his fantasy world. It's a fantasy world in which only he can save the other children from the onslaught of an evil giant robot. The protagonist transforms into a giant robot himself, blasting the intruder with his wrist laser, causing the villain to flee while he gains the glory and the girls. Cotter doesn't change his drawing style when his characters shift into these fantasy sequences, and so the whole thing becomes strangely surreal. Cotter's scratchy, Robert Crumb-like line and frumpy characters blend seamlessly with the clunky, dented metal of the robots. The only signifier Cotter gives us, to indicate that the giant robots are imaginary, is a cloud lettered with "poof" at the end of the sequence. It's a traditional indication for a relatively traditional childhood heroic fantasy, but what's fascinating about Cotter's use of both is that the fantasy is especially cruel (the evil robot steps on the heads of the kickball players, squishing them) and the "poof" is not used at all in later fantasy sequences. After the first one, he plays them all straight, allowing robots and humans and dead kitties with jetpack wings to coexist in a wonderful and terrible Midwestern reality.

I fell in love with this book, though, for two reasons: 1) The specific evocation of childhood -- Cotter's childhood, presumably, and his relationship with his younger brother. When the two boys are talking about the obscure He-Man character known as Moss Man, and the unique, strangely enticing smell of the action figure, I knew that Cotter and I (and thousands more from our generation) were kindred spirits. And 2) The unapologetic leaps from vignette to vignette, and from childhood to young adulthood and back again, without insulting the audience's intelligence. Cotter challenges the reader, jumping around in the narrative, showing what happens to the protagonist as a young adult, still the same awkward, eager-to-please, sad character, but with even more aggressive tendencies. With more anger. Cotter doesn't give us a simple narrative that says, "the character was picked on as a kid, so that messed him up later in life." Instead, Cotter weaves all of these sequences together to build a strong sense of place and identity. Whether it's truly autobiographical or not doesn't matter. Cotter has created something true and meaningful about the experience of growing up, and it's a powerful story.

Even after all the pain and misery and glimpses of contentment and maybe even joy, Cotter ends the book with a simple scene between the two brothers -- a scene from their younger days, before the protagonist turned into a much angrier young man. The scene takes place in a snowstorm and as the characters walk away, the snow covers their tracks, and the pages turn to whiteness, and then blankness. Unlike their footprints, the power of the story lingers, but ending the story in the snow is appropriate. Cotter has frozen these childhood moments in time, not with rosy nostalgia but with bleak honesty.

"Skyscrapers of the Midwest" deserves this hardcover edition, and it deserves all of the praise its received over the years. I'm embarrassed that it took me this long to finally dive into its pages, but now that I have, it's not a plunge that I'll ever forget.