What do you think of when you think of horror comics? Vintage EC shockers, black-clad Vertigo occult titles, weird and wild manga, modern-day success stories like 30 Days of Night and Hack/Slash, or the mother of all zombie comics The Walking Dead? For my money, the most reliably disturbing and disquieting work in the genre over recent years has come from artists who produce what you'd consider to be "alternative comics." These alt-horror cartoonists may not even think of themselves as horror-comics creators at all, eschewing as most of them do the rhythms and staples of conventional horror fiction. But by deploying altcomix' usual emphasis on tone and emotional effect in service of dark and macabre imagery, their comics haunt me all the more.

So for my contribution to Robot 666's daily horror-centric lists this week, I'm singing the praises of six talented alt-horror cartoonists. I could have listed quite a few more, mind you--some real giants of the field, including Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Charles Burns, Jim Woodring, and Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell have done tremendous work in this area. But for me right now, these were the six who demanded the spotlight.

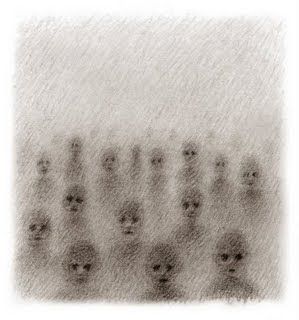

Renee French: You can make reasonably accurate comparisons to David Lynch with at least four of the six people on this list, but French may be the cartoonist whose work demands one the most. In particular, her frequently deformed (more like unformed) characters and hazy, dreamlike, soft-focus pencils recall Lynch's unnerving debut Eraserhead with its dust-mote cinematography and mewling infant thing. French's most recent books, The Ticking and Micrographica (both from Top Shelf), move away from the more direct body horror of her earlier collection Marbles in my Underpants. But they maintain a tone of quietly frightening vulnerability--like peeling up a floorboard to find some kind of fuzzy gray fungus pulsing beneath, or probing the soft spot on a baby's skull. And every so often, the work she's been posting on a daily basis to her blog will deliver a knockout blow of yikes-ness. [Buy French's comics at Top Shelf]

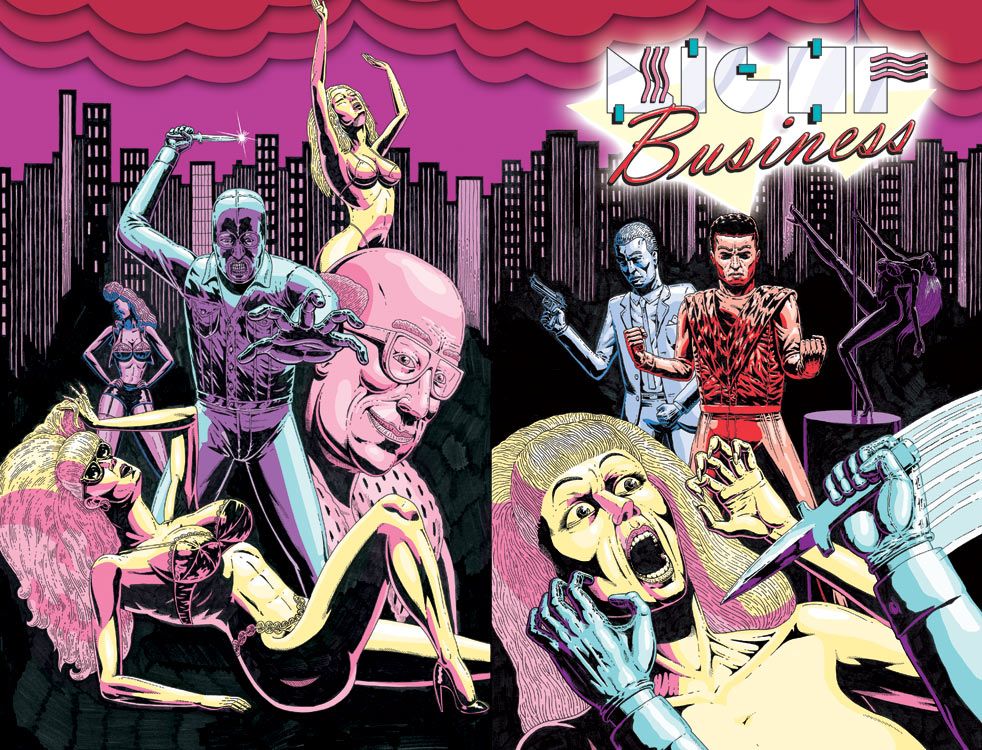

Benjamin Marra: "Discovered" by the Comics Comics crew and canonized as part of the "New Action" pseudo-movement of alt-genre comics, Marra is typically seen in the tradition of late-nite grindhouse '80s-indy-comic trash. And certainly his comics are steeped in enough Grand Theft Auto: Vice City-style thugs, babes, and '80s iconography to merit that outlook. But Marra says the most direct inspiration for his retro-thriller series Night Business was a fateful video-store binge on the '70s Italian slasher-horror genre known as giallo. Largely dispensing with plot in favor of gratuitous nudity and brutal yet artfully staged murders, these cult films--pioneered by directors Mario Bava and Dario Argento and boasting titles like Strip Nude for Your Killer and Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key--have found a true artistic heir in Marra, who's blended their seedy sensuality and gruesome gore with the vibe of forgotten '70s and '80s American genre comics into a truly singular comics experience. [Buy Marra's comics at his website]

Hans Rickheit: I could be wrong, but I feel like Rickheit is less interested in scaring you than any other artist on this list. It just so happens that his "normal" is grotesque and harrowing to the rest of us. His characters--in his Xeric-winning erotic-horror graphic novel Chloe, in his minicomic anthology series Chrome Fetus, and in his massive Fantagraphics hardcover The Squirrel Machine--explore strange, complex, semi-mechanical environments, discovering fleshy orifices, hideous hybrids, and strange secret dwellings where uncomfortably intimate activities are performed. His comics frequently end simply by showing us what his characters have discovered in their explorations, as though the act of seeing what they see is climactic and irrevocable. Couple it with a unique turn-of-the-century aesthetic (nobody use the s-word!) and you get comics that are sort of like if David Cronenberg tried to do Videodrome in the 1900s. [Buy Rickheit's comics at Fantagraphics and at his website]

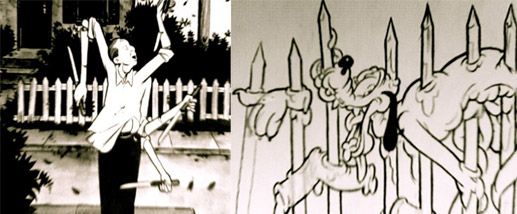

Al Columbia: Really there's nothing I can say about Columbia that hasn't already been said (better than I'd say it) by Robot 6's Chris Mautner in his "Collect This Now!" piece on Columbia's early works earlier this week. I'll simply add that maybe my favorite thing about Columbia's comics--many of which can now be found in his new Fantagraphics hardcover Pim and Francie--is how they look like the product of some doomed and demented animation studio. It's as though a team of expert craftsmen became trapped in their office sometime during the Depression and were forgotten about for decades, reduced to inbreeding, feeding on their own dead, and making human sacrifices to the mimeograph machine, and when the authorities finally stumbled across their charnel-house lair, this stuff is what they were working on in the darkness. And though Columbia's recent comeback has proven him capable of creeping us out without recourse to old-timey imagery (cf. his scenes-from-a-murder-scene strip "5:45 A.M." in MOME Vol. 11), the work for which he is best known smartly takes advantage of its seeming vintage pedigree. As anyone who's ever found themselves alone in an empty room with very old dolls, their eyes staring endlessly, time can make monsters out of almost anything. [Buy Columbia's comics at Fantagraphics]

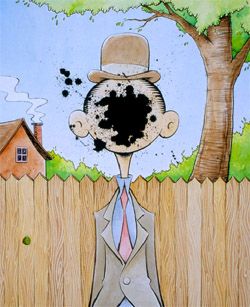

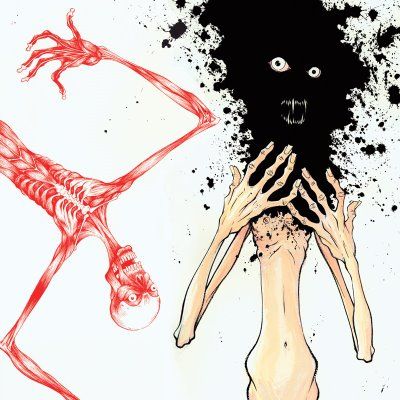

Tom Neely: Neely's another artist who specializes in character designs that recall classic cartooning from Popeye to Steamboat Willie, but unlike Columbia, that's not where he pulls the horror from. Instead, his knob-kneed, button-eyed characters find themselves adrift in imagery seemingly pulled from some black netherdimension. Sometimes Lovecraftian in scope, other times feeling more like the best heavy-metal album art never drawn, Neely's monsters--wolfmen, ravens and dogs, killers, and particularly the title, uh, thing from his self-published graphic novel The Blot--are all clearly rooted in the mental state of artist, character, and audience alike. They're exterior expressions of something scary within, a fear that in the face of the monstrousness of ourselves or others, we really are as helpless as Neely's frail everymen and everywomen. PS: He can do straight-out horror-comic homages like nobody's business, too. [Buy Neely's work at his website]

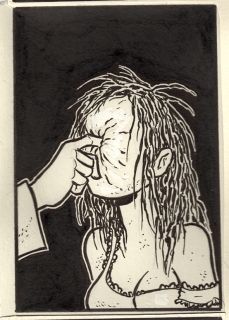

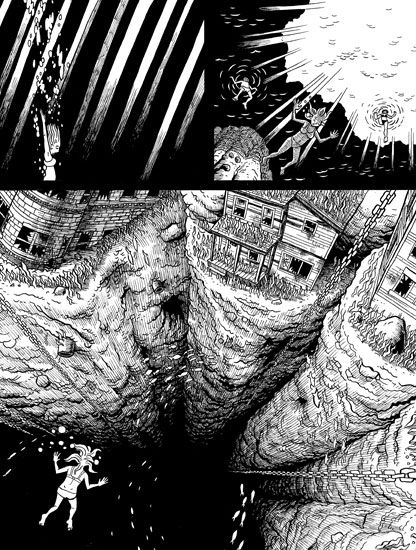

Josh Simmons: Whoa. Simmons is one of a very few comics creators still capable of shocking. His best-known claim to fame is House, a stark, largely silent work of survival horror that makes tremendous and relentless use of its crumbling, sprawling titular environment, and really put alt-horror on the comics map again. But as harsh as that book gets, it still can't prepare you for the utterly uncompromising, searingly angry horror he's been producing for anthologies and self-published minicomics. His Ignatz-nominated MOME strip "Jesus Christ" recasts the second coming as an anatomically-correct, genocidal giant-monster attack. His minicomic In a Land of Magic swerves from goofy fantasy-world parody to gut-churning sexual violence. His Kramers Ergot 7 contribution "Night of the Jibblers" is reminiscent of Clive Barker at his early best, transgressive splatterpunk that punishes the innocent and feeds on obscenity. His unauthorized Batman mini makes the Dark Knight darker than he's ever been, stripping away his heroism and recasting him as a sullenly psychopathic mutilator of the homeless. And his magnum opus, Cockbone, is a pornographically explicit story of incest and mutation without a glimmer of joy or hope in its pages. Simmons is doing serious, dangerous work. [Buy Simmons's comics at Fantagraphics]