Scott McCloud began his moderating of Gene Luen Yang's spotlight panel at Comic-Con International in classic comics style -- with visual aides.

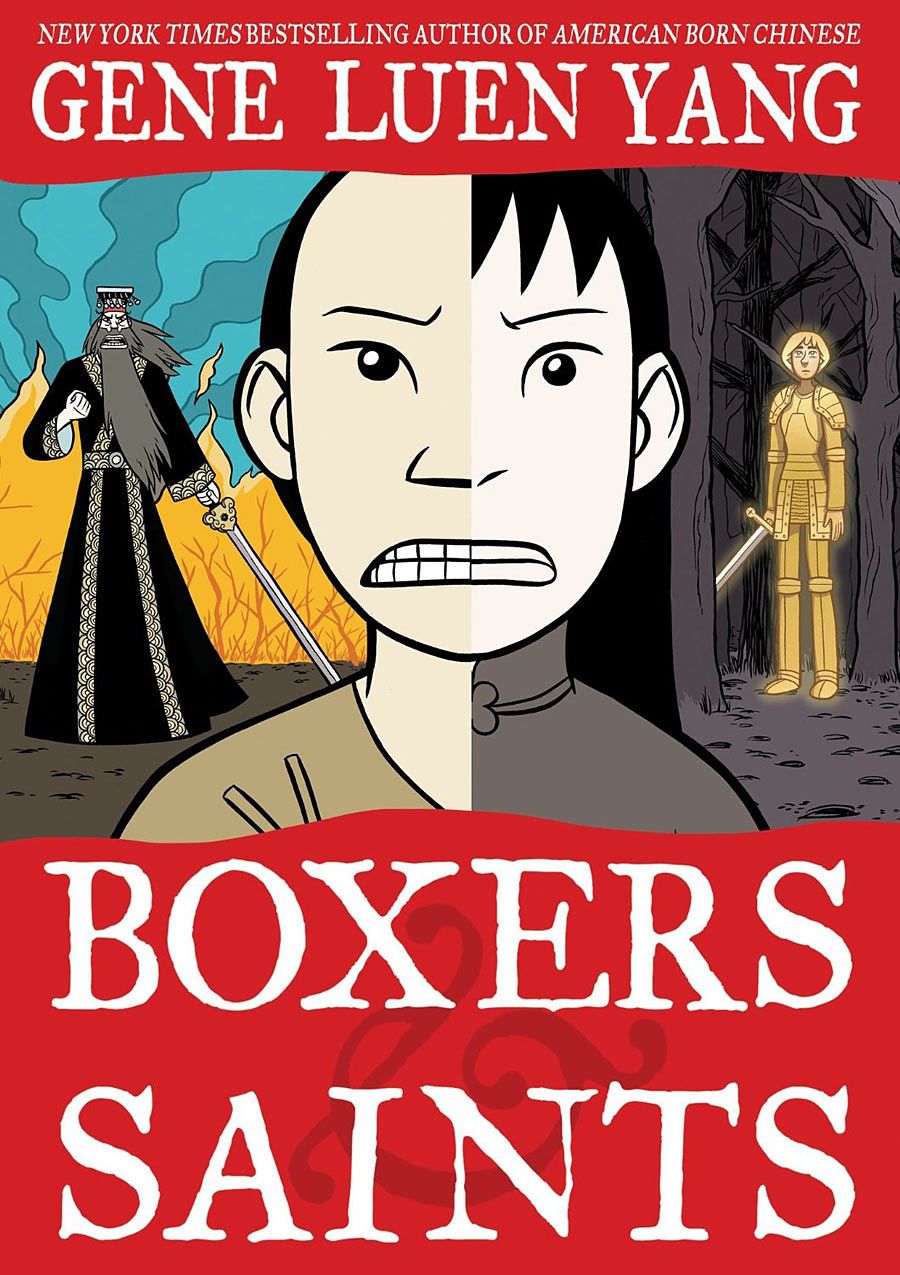

"I have a very specific question to start with," McCloud said, projecting photos of Yang's "Boxers & Saints" slipcase edition on the screen. "Do you ever just want to punch anyone who puts it in [the slipcase wrong]?" McCloud said, sharing an image of the two book set's spines framed in reverse order. Once the laughter subsided, the conversation got underway.

Yang said he read McCloud's "Understanding Comics" around age 19, and his fascination with the analytical graphic novel set him on his career -- a career whose most recent manifestation has been the dual release of "Boxers & Saints" and "The Shadow Hero" with artist Sonny Liew, both from First Second.

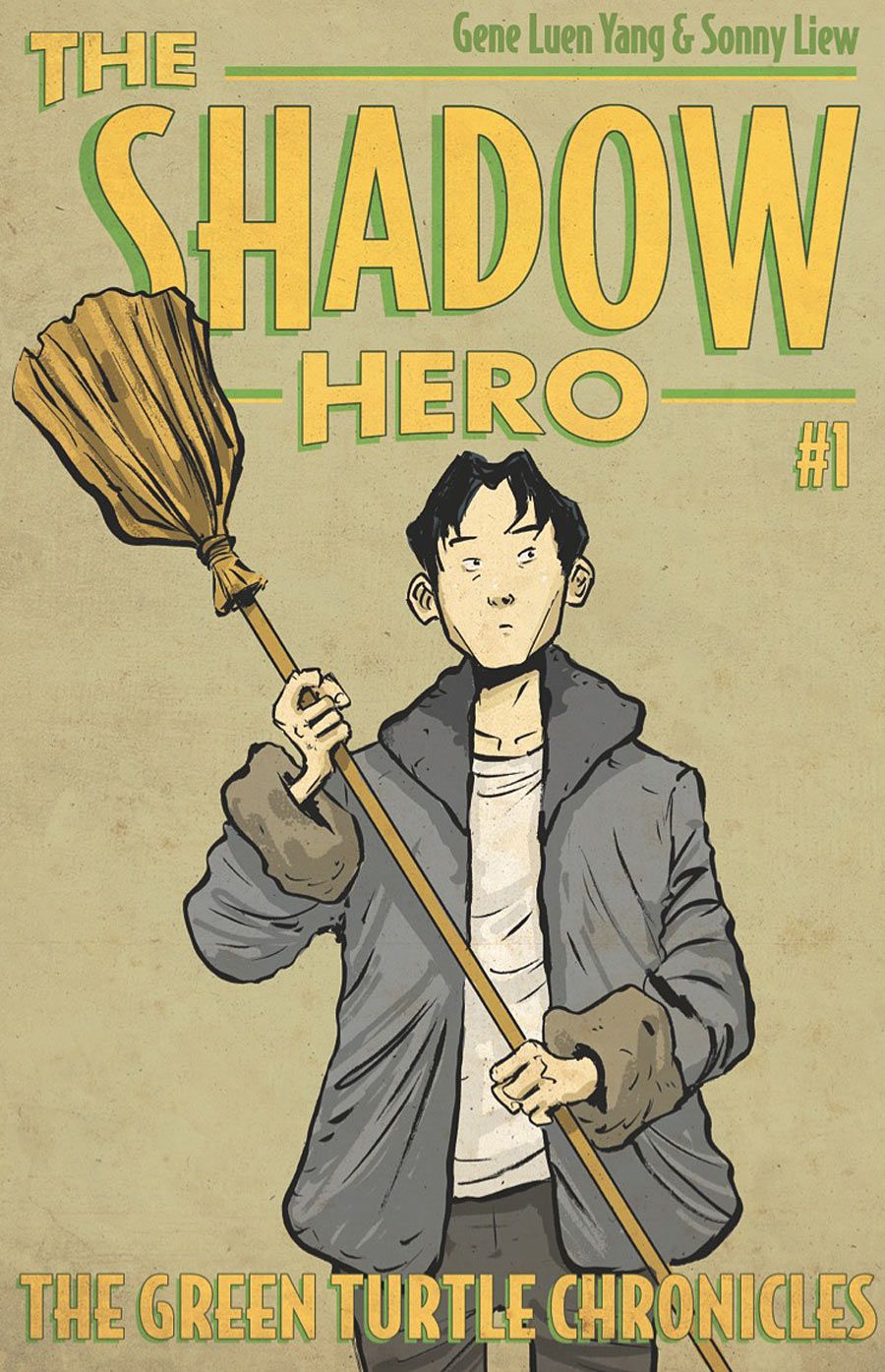

With the latter project, Yang explained that the Golden Age character The Green Turtle -- created by Chinese American cartoonist Chu Hing -- was meant by the artist to be a Chinese American hero, but his publisher denied those aspirations. "In classic cartoonist fashion, he responded passive aggressively," Yang said, noting that every issue of the original series finds creative ways to not show the hero's true identity. "The Shadow Hero" picks up the story of the character and fills in its intended background.

McCloud said he's found several themes in Yang's work, including the element of surprise. "You may be one of the most unpredictable writers on the planet," the interviewer said. McCloud recalled when he read Yang's "American Born Chinese" in its original mini-to-webcomics form and saw the built-on-stereotypes character Cousin Chin-Kee. He was astounded at the way in which Yang pushed the barriers of what stereotypes could do. Yang said when he first met McCloud, the cartoonist said to him, "It's such a good thing that you're Asian American."

"American Born Chinese" was undoubtedly Yang's breakout work (though not his first), and according to McCloud, it betrayed this idea that "even when you're examining injustice, you do it from a position of curiosity... that makes for a really interesting story."

Yang said he doubted he would have been able to pre-sell the book to a publisher because of its take on stereotypes; doing it on his own allowed him the freedom to take creative risks. "There's something about self-publishing that gives you this false sense of bravado. You don't worry about the audience," he said, admiring a similar quality in Michael Deforge's "Ant Colony."

Conversation turned to Yang's writing style, which McCloud said was very much a direct style in the mold of E.B. White. He read passages from "The Shadow Hero" that were direct. "I challenge you to take a single word out of that," he said after a particularly dramatic take on the text. Yang works both for his own cartooning while also writing comic scripts for other artists, a fact McCloud was surprised by. Yang said that collaboration meant "you're automatically telling a story in a mixed voice" which if you know going in can be a rewarding kind of creation.

But working on his own also has its unique rewards. With "Boxers & Saints," the clash of Eastern and Western ways of viewing the world inherent in the story of China's Boxer Rebellion was a theme so close to Yang's heart that he couldn't imagine doing it with someone else (aside from colorist Lark Pien, who helped correct Yang's self-described "terrible color sense"). However, with "The Shadow Hero," the style of the superhero world necessitated another voice to support Yang's ideas.

Mythology and belief's role in Yang's work runs through "Boxers & Saints" and "American Born Chinese," as McCloud explained, particularly in a way that literalizes the beliefs of his characters. "It makes the book absolutely fascinating, but not easily resolved in the mind. Where does reality begin and end?" McCloud asked of "Boxers." As a person who grew up within a Catholic family and took his own journey to embracing his own faith, Yang said he felt a strong connection between religion and story. "I wanted to show that within a comic book, and because comics are visual, having a story embody itself so that the person invested in the story could experience it made sense," he said. "The story embodies the culture in a way that extends beyond the individual."

In discussing the intricacies of the various Gospels, McCloud said he'd love to see Yang adapt the Gnostic gospels for comics to make "teenage superhero Jesus" in a way others couldn't.

One of the biggest crossover hits in recent comics history is Yang's work on Dark Horse's canonical continuation of Nickelodeon's "Avatar: The Last Airbender" animated series. McCloud and Yang both share a love of the original series -- and an ambivalence to seeing the reviled M. Night Shyamalan live action adaptation.

"'Avatar' starts out good, and then something happens," McCloud said of the series to which Yang replied "It turns into crack!" Yang was hooked early, but he said the addition of the blind character of Toph really elevated the way the series looked at its characters. "The whole series is about an embodiment of contradictions," Yang said. "[Ang] by nature wants to be a free spirit -- an 1800s Asian hippie -- but he also feels this tremendous responsibility to the world around him."

The pair recalled how Yang became associated with the franchise, being a powerful voice of dissent when the film version of the series heavily influenced by Asian culture was cast with nearly all white actors. That reputation (via an online comic lambasting the move) brought the artist's work to the attention of Dark Horse, and McCloud said that unlike so much internet outrage, Yang's response was a measured and understood take on why the mistakes in casting took place. Yang agreed, saying that he felt the move wasn't racist on the filmmakers part but a misguided attempt at making their version more marketable...a move that blew up in their face.

Creatively, the pair talked about the "planners versus pantsers" approach to writing. Both Yang and McCloud are planners, who outline their works in detail, as opposed to "pantsers," who fly by the seat of their pants. Both men joked that their engineer fathers may have had an influence on their approach. On the technological front, Yang is attempting to move into the future by working on a Wacom tablet rather than a traditional drawing board, but after a year and a half of playing with it, he still prefers the classic methods.

Yang said that like many other creators who work for the YA and Children's market, he never considered himself a person who was creating with a specific age group in mind. He said that he's gotten a wide range of response from readers, but he often lectures and presents his books to a high school audience.

Opening the floor to fan questions, someone wanted to know why "American Born Chinese" was semi-autobiographical instead of straight autobiography. "Because I am a chicken!" Yang replied. More seriously, he explained that leaning into magical realism in comics opened up narrative possibilities that straight memoir would not allow for.

The "each book stands on its own" form of "Boxers & Saints" was asked after by a fan who had never seen a narrative structured that way. "I was hoping that each book would stand alone, but if you read them in tandem, you'd get something more. And you know who does that? Marvel Comics does that," Yang joked.

Yang said he was spoiled in his first collaborative comic since he worked with friend Derek Kirk Kim -- himself an accomplished cartoonist. "From a writer's perspective, it's awesome because I'd send him these thumbnails, and in a few weeks these gorgeous pages would come back with no sweat off my brow," he said.