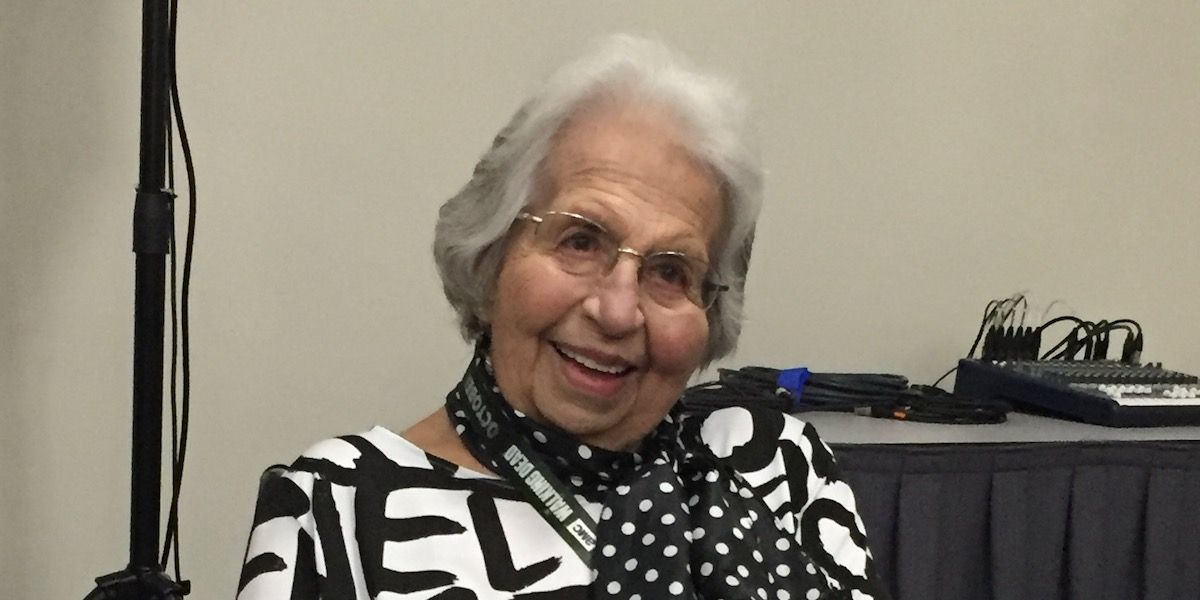

Ruth Goldschmiedova Sax greeted the crowd that filled the panel room with a smile. “If I look around the room, I see that my life has gone from Holocaust hell to, now, Comic-Con,” she said.

Sax, who is 90 and uses a wheelchair, was the first speaker at the “Art and the Holocaust” panel at Comic-Con International in San Diego, and she captivated the room with her first-hand account of spending time in three concentration camps, including Auschwitz, and facing the notorious Dr. Mengele six times. Mengele decided who lived and who died, and the young and the ill were always marked for death, so Sax smeared her cheeks with the red dye from coffee wrappers to make herself look older and healthier.

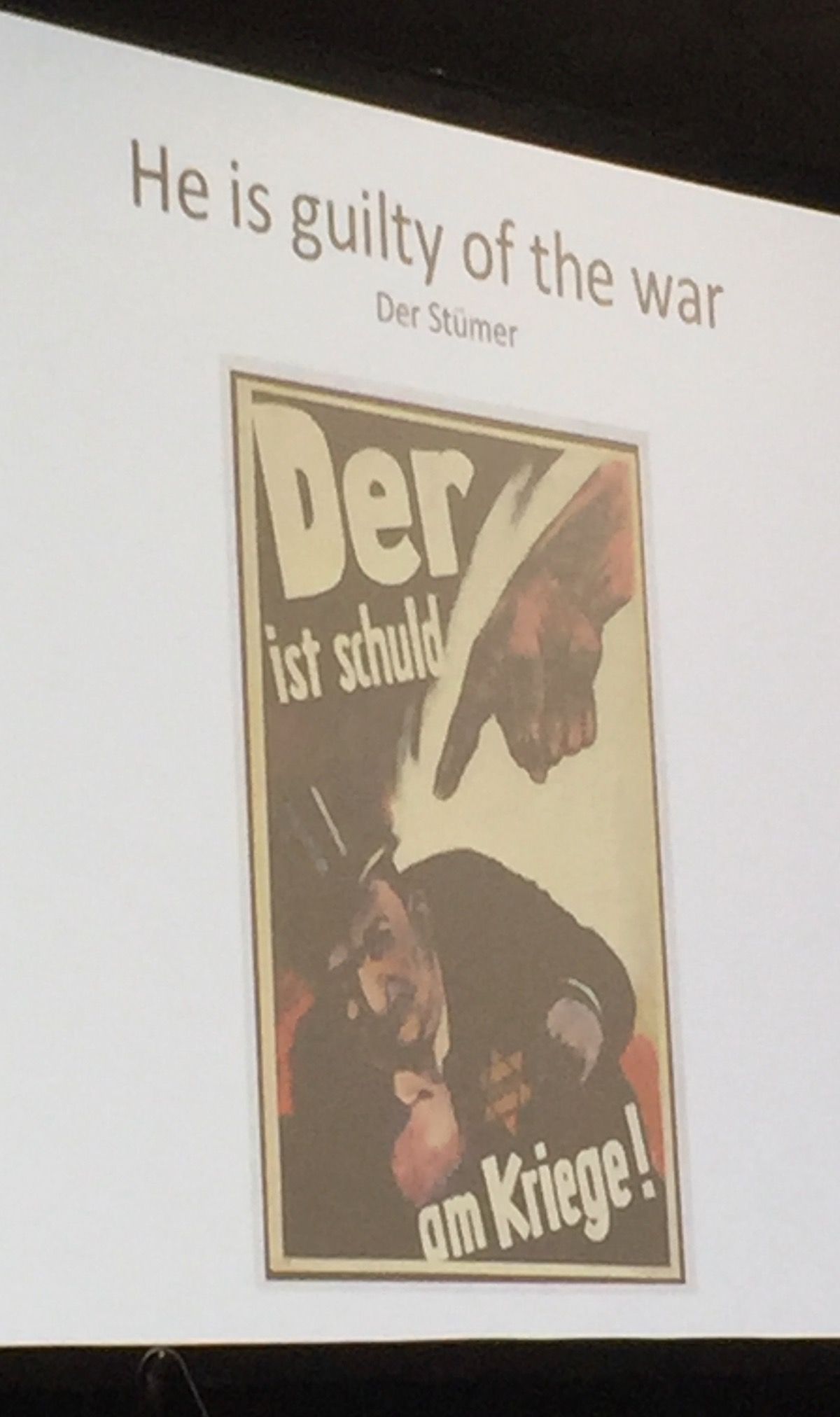

The impact of art came early for Sax, who recalled seeing anti-Semitic cartoons in the German magazine Der Sturmer. “We were shocked and surprised by the propaganda and the way Jewish persons were portrayed,” she said. “I remember being scared, wondering how this could be. It was something we could not run away from.”

Born in 1928, Sax grew up in Moravia, a region of the Czech Republic, and she was 11 years old when the Nazis invaded in 1939.

“The Nazis felt free to take what they wanted, including the family car,” said Sax. “After the invasion, it was impossible to be sheltered by my parents, and being a Jew was a way of life that could not be escaped.”

The family had to wear gold stars identifying themselves as Jews, and their freedoms were gradually taken away. In 1941, they were arrested and transported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. At the panel, Sax showed a photo of herself taken two days before she was arrested; she retrieved the camera after the war and had the film developed. The outfit in the photo is the one she was wearing when she entered the concentration camp.

Later, she was transferred to a camp in Oederan, Germany, where she was forced to work in a munitions factory making bullets. She put sand in the bullets to they would not be usable, an action that she said saved many lives. After Oederan, Sax and her mother were transferred to Auschwitz, and then back to Theresienstadt, where they remained till the end of the war. Sax and her daughter Sandra Scheller collaborated on a book, Try to Remember -- Never Forget, which recounts her experiences more fully.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='Inside The Concentration Camps, Art Helped Some Survive']

While Sax held the room spellbound with her first-hand testimony, the most dramatic moment came with the showing of rarely seen drawings of the removal of the bodies of 335 partisans who were executed in a cave in 1944 as revenge for the killing of 33 German police officers. Nazi soldiers shot each victim in the back of the head and then blew up the cave so it couldn’t be found. The caves were found, however, and the drawings, by an American soldier, document the scene in the caves, the removal of the bodies and the examination of the crime scene. Scheller asked for a moment of silence as the drawings were being shown. (The drawings, which were sold at auction in 2017, can be seen here.)

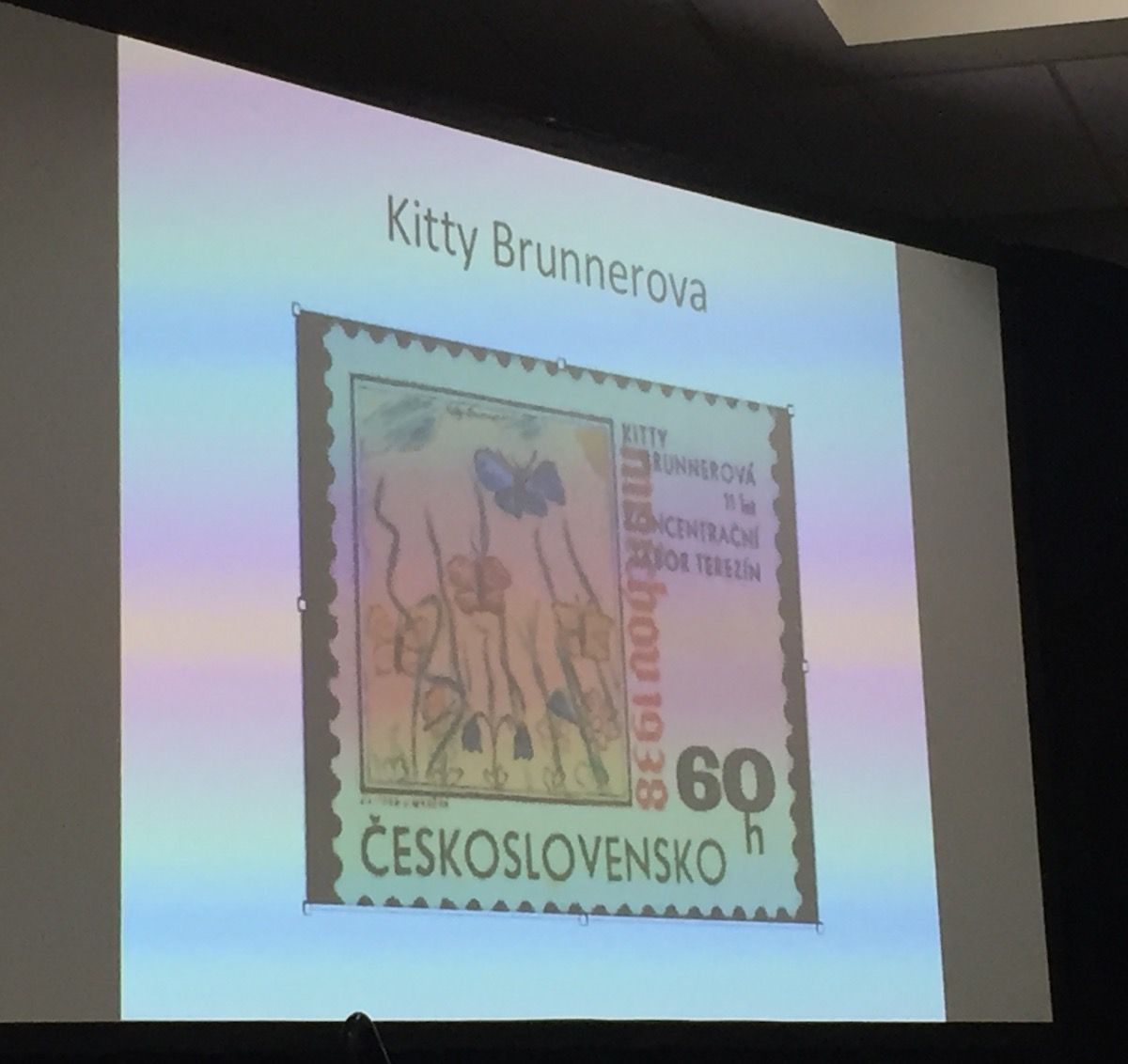

Sax’s daughter, Sandra Scheller, discussed three artists of the Holocaust who had personal connections with her family. The first was her cousin, Kitty Brunnarova, who died at Auschwitz. Some of her artwork was found under her pillow, and a painting of butterflies that she did at age 11 was made into a postage stamp in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s.

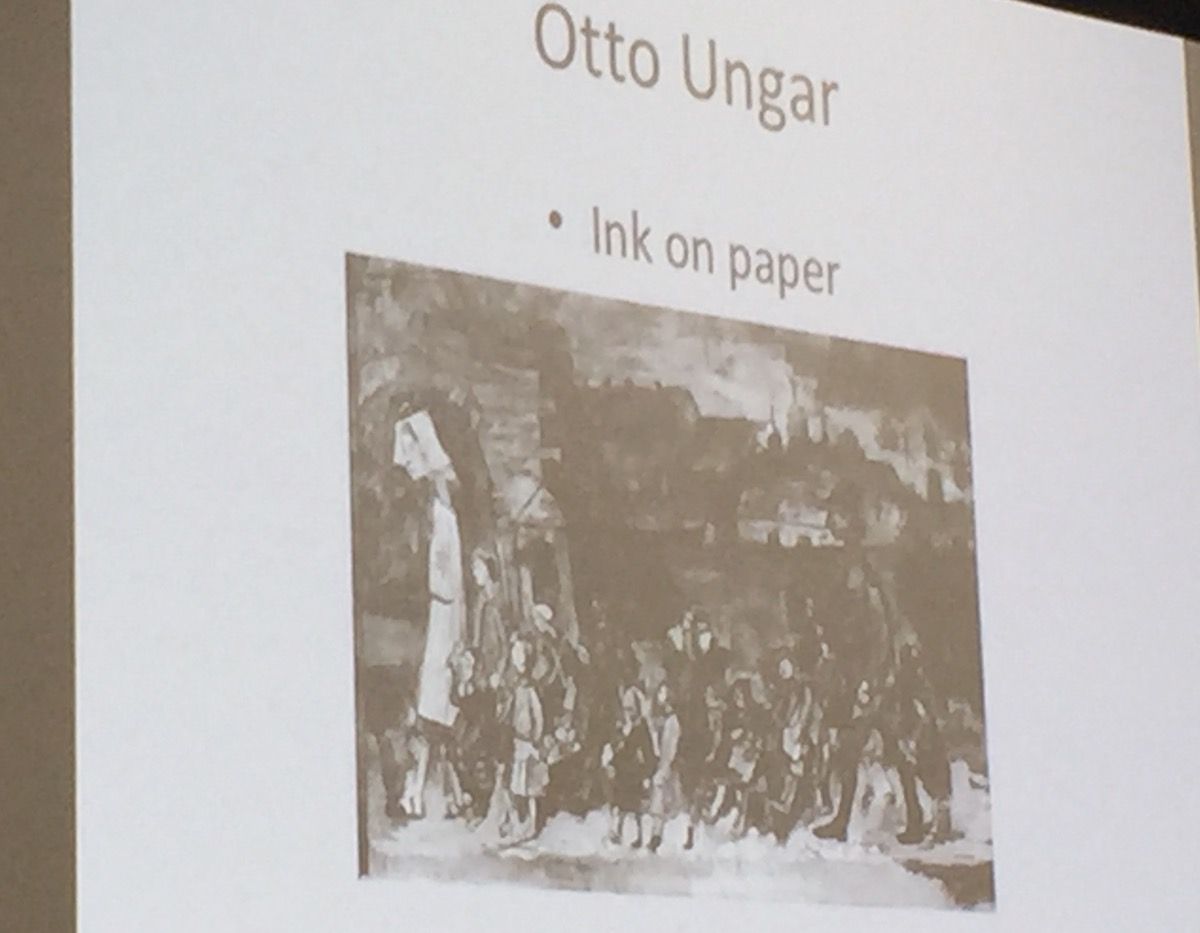

Scheller also showed some drawings of daily life in Theresienstadt by Sax’s art teacher, Otto Ungar, who was tortured when his artwork was discovered. The Nazis beat his drawing hand so badly that two of his fingers had to be amputated.

Dina Babbitt, whose daughter was a friend of Scheller’s, painted a mural of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on the back wall of the children’s barracks in Auschwitz. Her talent saved both her and her mother: Dr. Mengele recruited Babbitt to do paintings of the prisoners, in order to accurately depict their skin tones. Dina refused to do so unless her mother, who was in line for the gas chambers, was spared. Mengele complied. Years later, Babbitt returned to Auschwitz and asked for her paintings back, but the museum refused to release them. A number of American politicians and artists took up her cause, and her story was made into a comic penciled by Neal Adams and inked by Joe Kubert.

Another panelist, Esther Finder, spoke about superhero comics on the American side of the ocean. She pointed out the parallels between the story of Moses and the story of Superman, the latter created by two Jews whose families had fled Europe before the war. While the Nazis believed in survival of the fittest, which meant trampling the weak, the American Superman was kind, moral and protected the week. Many other superhero creators were also Jews, working in comics at times when they were widely discriminated against in other industries.

“As a Jew, I took pride in knowing the books I enjoyed reading were created by Jews,” said Robert Scott, owner of Comickaze Comics in San Diego. “It's definitely not a coincidence that the majority of the characters that were built to inspire, characters like Captain America, Superman, all of the characters that we are seeing in movies today, were created by first generation Americans, immigrants who came here for whatever reason."

Igor Goldkind, the moderator, opened and closed the panel with reflections of his father, who was a veteran. At the beginning, he recalled his father telling him that the reason the Nazis succeeded was that they dehumanize people, treating them not as human beings but as commodities. "If there is something not to forget, that is the thing," he said.

“I asked my father how could the German people have done this?" said Goldkind at the end of the panel. "They are one of the most civilized cultures in the 20th century. How could these people have orchestrated these crimes. My father explained it was because they are just like us -- there is no 'other' that commits these crimes. 'They are people like us,' he said. 'Nice, comfortable, middle-class family people who wind up, through manipulation, propaganda and lies, being manipulated into committing the most hideous crimes imaginable.' The lesson is not [only] about the past … but also about how the past continues to inform the present."