We've noticed some confusion surrounding Marvel's big announcement about its acquisition of Marvelman. Namely, some are wondering why this is big news, or asking who this Marvelman is anyway.

Fear not, we can help. After the break you'll find a guide to the whys and wherefores of Marvelman and why this really, truly is a really, really big deal.

Note: Parts of this article originally appeared here, as part of the "Collect This Now!"feature. It's been refurbished quite a bit, though.

So who is this Marvelman character, and why should I care?

First of all, we should explain that the Marvelman character was known in the United States as Miracleman. That may be where part of the confusion is coming from.

Why did they rename the character?

Because Marvel objected to the title. Funny world, innit?

Hold on there. You're getting way ahead of yourself. Start at the very beginning: Who is this character and who created him?

Marvelman was created in 1954 by British artist/writer Mick Anglo. Marvelman was basically a god-like superhero whose secret identity was a boy reporter named Michael Moran. Moran only had to say his magic word "Kimota" (pronounce it backward) to turn into a magnificent physical specimen with extraordinary abilities.

That sounds an awful lot like DC's Captain Marvel.

Yes, indeed. He is, for want of a better word, a Captain Marvel rip-off. You see, prior to '54, a man named Len Miller had been reprinting Captain Marvel stories in the U.K. But when Fawcett Comics, owner of the Big Red Cheese, had folded up shop, unable to win its lengthy legal battle against DC (and that's another story in and of itself), Miller turned to Anglo to create a similar character. Anglo chronicled the adventures of Marvelman, and his friends Kid Marvelman and Young Marvelman until about 1963, when the series came to a close.

OK, so Marvel bought a second-rate Shazam. Why should I care about this again?

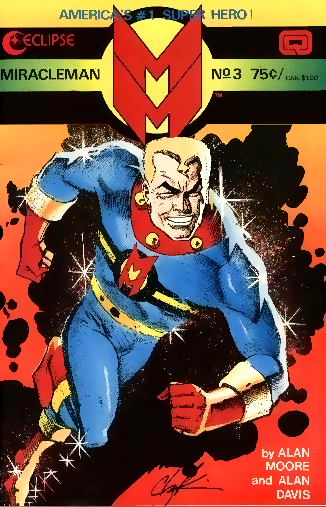

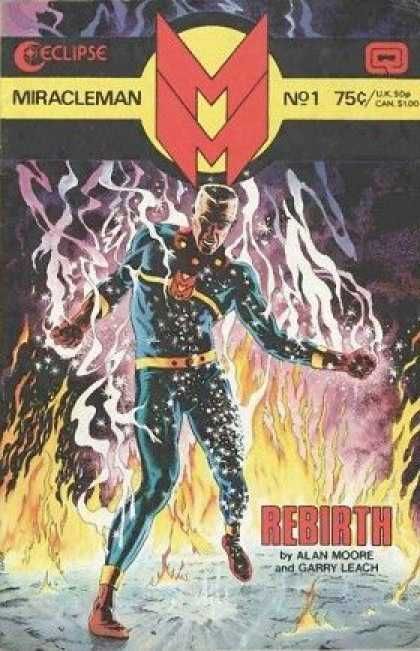

Two words: Alan. Moore. In 1982 Moore was hired by the new Warrior magazine, along with artists Gary Leach and Alan Davis, to bring back and re-interpret Marvelman. Their vision fit perfectly in the gritty, more "realistic" framework of fantasy stories that Warrior and other comic magazines were creating at the time.

These stories featured a grown-up Moran, now pushing 40. Having completely forgotten about his years as a superhero, he works as a freelance reporter, and is frequently depressed and given to migraines. Then, while on assignment, he gets caught in the middle of a terrorist raid, remembers his magic word and transforms once again into Marvelman, ready to rid the world of evil.

OK, I like Moore and all, but that sounds kind of boring.

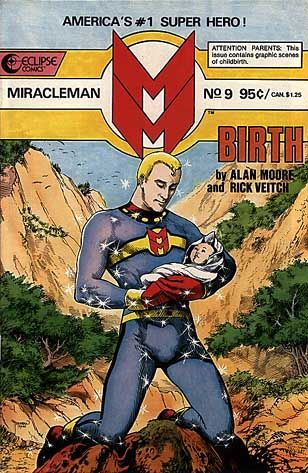

I haven't gotten to the good part yet. It turns out the memories that Moran has of his youth and origin are suspect, to put it mildly. The seemingly cartoon villain he believed to be his nemesis was the force responsible for his creation and has returned to finish his experiments. His former teen-age sidekick Kid Miracleman has grown up to be the most psychotic and dangerous being alive. Oh, and his wife is pregnant.

Been there, done that. This sort of revamping goes on all the time.

True. These days, the "everything-you-know-is-wrong" character reinvention has become a cliche. But it's important to remember it was a relatively new idea when Moore came along. More significantly, Moore's ultimate aim with the series is a lot grander and philosophical than merely shifting the tone and upping the violence quotient to fit a more cynical readership.

But I like violence. Lots of violence.

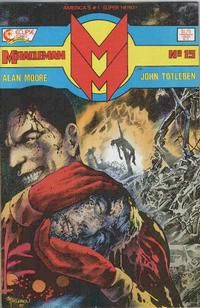

Then you're in luck. Because if Marvelman is remembered for anything, it's Issue 15, easily one of the darkest, most violent comics not only in Moore's canon but quite likely in the medium ever (and I've read S. Clay Wilson). In the issue, a gibbering Kid Miracleman battles his former partner and friends, leveling London, with little left to the imagination as to the type of carnage wrought. John Totleben's art is chaotic and gruesome, with wreckage, severed limbs, dead bodies and other horrors crowding and choking each page.

Again, it's a distinct rejoinder to the fan's wish/wonderment of "What if superheroes really existed?" Well, Moore reminds us,they'd lay to waste the world around you. They'd destroy everything you ever believed in and replace it with a world that, while it might be filled with wonders and triumphs, would deny you your basic humanity. Beyond simple genre subversion, though, Moore is explicitly pointing out -- as he did from a different perspective in V for Vendetta -- the danger inherent in attempting to create any utopia, super-powered or otherwise.

You know, the more you describe this, the more it sounds a lot like Watchmen.

As with Watchmen, Marvelman explores the idea of what life would be like in a world with god-like superheroes. Parallel themes of the corruption of power, individual responsibility and such abound. As with Ozymandias, Marvelman does indeed ultimately save the world, reshaping it into a divine utopia, though not without a severe cost.

Because of the similarities, Marvelman tends to get seen as Watchmen redux, even though it was first down the pike. Certainly it's not as tight a story -- it's a sprawling work that took several years to complete and had a revolving door of artists. In addition to Leach and Davis, Rick Veitch and, finally, Totleben made significant marks on the series.

But if Marvelman lacks the clock-like craftsmanship of its big brother, it nevertheless remains a compelling work, full of stunning, indelible sequences and characters. At times it's almost operatic whereas Watchmen is more like a concerto.

Your musical analogies leave something to be desired. So what happened after Moore finished the series?

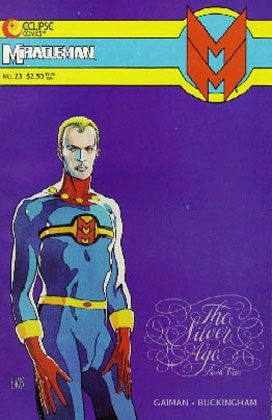

Two more words: Neil. Gaiman. After wrapping up the series with Issue 16, Moore handed the reins (and what he thought were his share of the rights) to Gaiman, who picked up and poked and prodded at what Moore had left behind, sometimes brilliantly. Sometimes not so.

Unfortunately, Gaiman never got the chance to finish his tale, and the series ended at Issue 24.

Why?

Eclipse Comics, which had by this time taken over publishing the series, went belly-up in 1994.

From there it gets complicated. To keep it short, Gaiman, Todd McFarlane and various other folks, have been fighting over the rights to the character in court ever since. Both thought they had at least partial ownership, as McFarlane had bought the rights to Eclipse's creative assets. Turns out Anglo had the rights all this time, and indeed, had never given the rights to Warrior in the first place. But it's taken years and years of wrangling and legal briefs to get this point.

How come I've never heard of this series before?

Because all those original stories have been out of print for a decade or more, and are harder than hen's teeth to find online and a lot more expensive to boot (though I understand there's the occasional BitTorrent file to be found, not that we approve of that sort of thing).

So will Moore's and Gaiman's series finally see the light of day again?

Let's hope so, as these are great stories and No. 1 on my list of books that need to be reprinted right now. Marvel certainly wouldn't have bought the rights to the character if it didn't at some point want to republish the long-lost Moore (and Gaiman) masterpiece.

Marvel now owns the rights to Anglo's stories from the '50s and will no doubt publish those in some fashion soon. But it's still unclear how much rights Moore (not to mention Davis, Buckingham or any of the other artists) have regarding republishing their work. Gaiman apparently helped broker the deal, though, and Marvel is in talks with the various creators. Certainly the chances of seeing a Miracleman Omnibus in the next year or two seems more likely than ever. And that's kind of stunning.

This isn't nearly enough Marvelman information. I want more.

For more on Marvelman, visit here, here, here and here. You may also want to buy a copy of this.