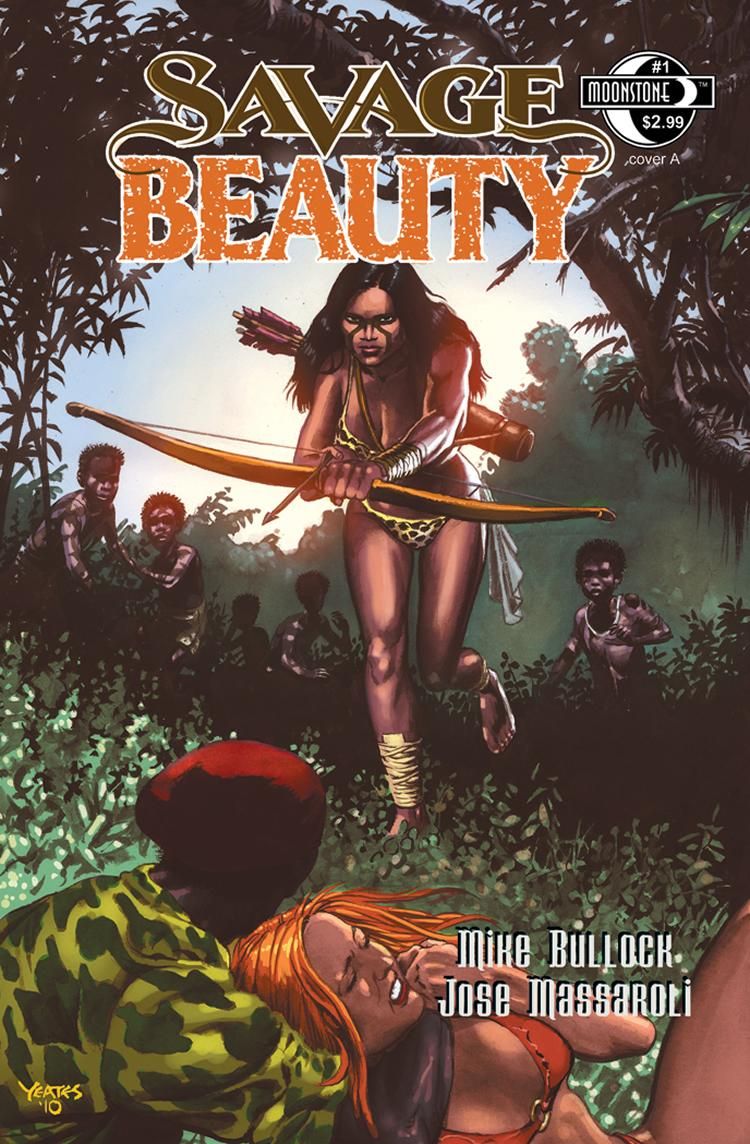

Writer Mike Bullock attracted attention during his run on The Phantom by pitting the Ghost Who Walks against analogues of real-life villains like Joseph Kony and his Lord's Resistance Army to raise awareness about the situation in Uganda and its surrounding area. Bullock has carried that mission into his latest jungle-adventure comic Savage Beauty.

As a fan of jungle-adventure stories (in fact, I wrote a text piece for Savage Beauty #1 talking about my fondness for the genre), I was curious about the challenges involved in Bullock's approach and in writing African-set adventure stories in general without resorting to clichés.

Savage Beauty #1 hits comics shops tomorrow.

Michael May: I want to ask you about some of the challenges in writing about Africa in adventure comics, but first, can you give me a sense of your own experience with the continent? What’s drawn you to it?

Mike Bullock: Prior to working on The Phantom at Moonstone I didn’t know much at all except what I’d seen in movies, TV, and the occasional magazine article. Then, it just so happened that my mother-in-law went to Uganda with Compassion International to visit a child she sponsored. Right after she returned, my father-in-law, wife, and I went out to lunch with another woman who had gone on the trip as well. She spent about an hour detailing the plight of the Night Commuters, the tyranny of Joseph Kony (the man originally credited with using children as soldiers) and the persecution of the Acholi people.

I’ve always had a heart for kids and listening to what Kony was (and still is) doing to the children of an entire culture made my blood boil. As these things go, it turned out one of my close friends had grown up with one of the guys who worked for Invisible Children. Before long I was elbows deep in their mission, doing whatever I could as a comic writer to help them and the Acholi people.

What are Africa’s major problems as you see them?

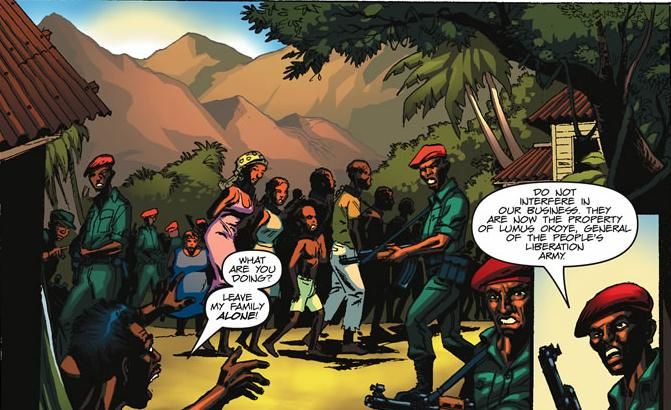

Well, I’m certainly no expert on the problems of an entire continent, but what rings my bell is the issues of tyranny and child abuse perpetrated by the Lord’s Resistance Army and similar villains. When someone can, with impunity, steal a child from their parent’s home, torture the child mentally, physically and spiritually, drug the child and brain wash them into taking a machete to their own parents, I have an issue with that. A big one. Honestly, I’d love to give Kony what we used to call the old “Welcome to DC” two-by-four upside the head, but since that’s beyond my power, I’ll continue to fight him the only way I can, in the pages of comic books.

What kind of research have you had to do to familiarize yourself with the situation over there?

I’ve spent countless hours pouring through AP articles, reading news from sources native to the region, and watching videos and documentaries of the issue. Ed Catto (of Captain Action Enterprises) and I exchange news links constantly, and I have a variety of documentaries on disc.

Was including these issues in The Phantom your idea or something that Moonstone came up with? Was there any persuading on either side that needed to take place?

While I was still having lunch with the woman who told me about Kony, I excused myself from the table, walked outside the restaurant, called Joe Gentile at Moonstone, and said, “I have a story I want to tell.” I informed him of what I’d just learned, he agreed that this is exactly the sort of thing the Phantom’s creator Lee Falk would have written about were he still alive, and then he told me to get to work on it. We later discussed involving Invisible Children and the rest is history.

Do you also touch on positive aspects of Africa in your writing?

I like to think I do as much as can be done within the confines of a fictitious adventure story. I’ve always tried to include good people, who reflect the hearts of most I’ve ever met from the region, and I’ve always tried to accentuate the natural beauty of the land as well. These are the things that really provide the stark contrast to the black hearts of men like Kony.

What’s the reaction been from readers?

More positive than I expected. The first Invisible Children arc has been named as one of the most influential post-Falk era Phantom stories ever done and it landed in Tony Isabella’s 1000 Comic Books You Must Read. Copies of it have made it all the way into the hands of government officials in Uganda who, I was told, lamented that they didn’t have a real-life Phantom to take out the LRA.

This approach of marrying real-world issues with adventure fiction seems like a tough line to walk. Go too far one way and it’s no longer entertaining; too far the other and you risk trivializing the suffering of real people. How do you strike a balance between depicting serious problems and having costumed adventurers running around the jungle with animal companions and/or super-powers?

Well, the super powers thing is easy, since Phantom has none and we purposefully didn’t give any to Liv or Lacy in Savage Beauty. As for walking the fine line, I just tell the stories the way I believe they should be told. I certainly don’t think these issues should be trivialized and based on reader response, that ideal shines through in the finished product. In the end, I just hope readers enjoy it and it makes some of them act on what they learn about child soldiers, human trafficking and other atrocities.

I’ve read the first issue of Savage Beauty and a couple of things stand out to me that I love. One is that there’s not just one hero, but two. What was the inspiration for that?

Initially, Ed Catto brought the springboard to me and said he had an idea for a jungle heroine who had a best friend/sidekick type. I began researching African mythology to build the mythos of Anaya, the Goddess in Savage Beauty, and found a legend of a mythical being who had a dual persona. That seemed to offer a lot of story dynamics I could explore, so I went back to Ed and suggested we give each girl equal billing. We bounced a few ideas around and landed on the half-sisters concept and I built the rest from there.

You mentioned that Liv and Lacy don’t have powers, but they do seem to be connected to Anaya in some way. Is Anaya a real, supernatural being in Savage Beauty or just a myth that the women exploit to intimidate their enemies? Or is it too soon to ask that?

I'd rather not say [yet].

Fair enough. Another thing I love is that one of the women is Kenyan. Amongst all the jungle girl characters in history, we can probably count the non-white ones on one hand, so that’s a refreshing choice. But something I wonder about is that while she was born in Africa, Liv is very much a Western girl. Why not make her purely African?

Back when I was in my early 20s and I was touring and recording with my old bands, we always used to joke about making millions on hit records, then dropping off the grid to some beautiful, exotic locale. Right before Ed came to me with the initial idea, I’d met a fellow who was very wealthy. He pulled his kids out of school for a month every year and went to Kenya, where he owned a ranch. He showed me pictures and honestly, it was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen in my life. Needless to say, Kenya immediately became my new place to drop off the grid to in my silly “If I win the Powerball” dreams. So, when I concocted the history of Lacy and Liv, it made sense for Lacy’s father to move his family to Kenya when he decided to drop off the grid, where they met and eventually adopted Liv. It then seemed right for the overall mythos that both girls would return to the US; where they would (unknown to them at the time) receive training for their eventual roles as Anaya.

Is there a concern that readers will come away with the message that Africa’s help comes solely from the West? Or is that valid message? To what extent should Africa be involved in its own solutions? How is that piece of the discussion reflected in Savage Beauty?

First, I’d like to clarify that the notion the entire continent needs anyone’s help doesn’t jive with my perception of it. Just as there are gang bangers and drug dealers and car thieves, etc in the US amidst the vast majority of good, law abiding citizens, the same is true in the countries of Africa. For every Joseph Kony there are hundreds of thousands of good people. But, every adventure story needs a villain. As far as how the help is reflected in Savage Beauty, the benefactor of the entire Anaya mythos is an entrepreneur from Ethiopia named Mr. Eden. He calls the shots, funds the missions and essentially sits at the head of the table when all is said and done.

What can you tell me about TRI and Invisible Children? What are their goals and how is Moonstone and Savage Beauty involved with them?

Invisible Children was founded when three film students flew to the Sudan to film a documentary about wildlife, if memory serves. They meandered around, filming nothing of any great interest as far as the stuff of exciting film goes and accidentally crossed the border into Uganda where they stumbled right into the child soldier phenomenon and met many families with children who were involved in the night commuting. They made their film, brought it back to the US with righteous outrage burning in their hearts and did whatever they could to draw attention to this issue. What started out as an attempt to shoot a low budget film for kicks, turned into a movement that now involves millions of people who want to see justice done. Moonstone and Team Savage Beauty are numbered in those millions, donating time, money, ad space and word of mouth to help the cause.