I'll just tell you up front -- there's a fair amount of profanity in this one, so if that bothers you, or you read these at work (on your lunch hour, of course!) and your workplace has filters, well, there might be an issue.

Yes, I could have used some work-around with asterisks or whatever, I suppose. The plain truth is that I didn't because it irritates me beyond belief when people do that.

For example, every week I see some idiot ad on CBS where they say, "...William Shatner in Bleep My Dad Says." They don't really bleep anything; instead, the announcer actually says the word "bleep," which makes it even sillier. Lately they've raised the ante by having Shatner himself say, "And stay tuned for my new hit show, Bleep My Dad Says." Still just saying the word.

It's completely absurd. We all know the title of the show is Shit My Dad Says. The reason is because it's based on the

Twitter feed of that name. CBS pays the guy a royalty. We should just all get over this as a nation and let the show's real name-- that CBS paid a ridiculous amount of real money to get the rights to-- be used on the air without anyone freaking out.

Therefore, this week, in an effort to help us get over our national neurosis, I will not be bleeping anything. Or typing silly shit like, uh, $#!+. (Our international readers, who are already over it, are probably already wondering why I bothered to spend this much time talking about this.)

So there's my pre-emptive preamble. Okay? Actual column follows. Oh, yeah, NSFW.

*

Not too long ago our other Greg did a really

rather magnificent survey of all DC's January books. At one point, and I'm paraphrasing, Mr. Burgas opined that it's idiotic to introduce real-world problems into a superhero comic, because obviously the hero can't solve them and just comes off looking like an ineffectual tool.

This neatly sums up the problem I've had with a lot of superhero comics over the last decade or so.

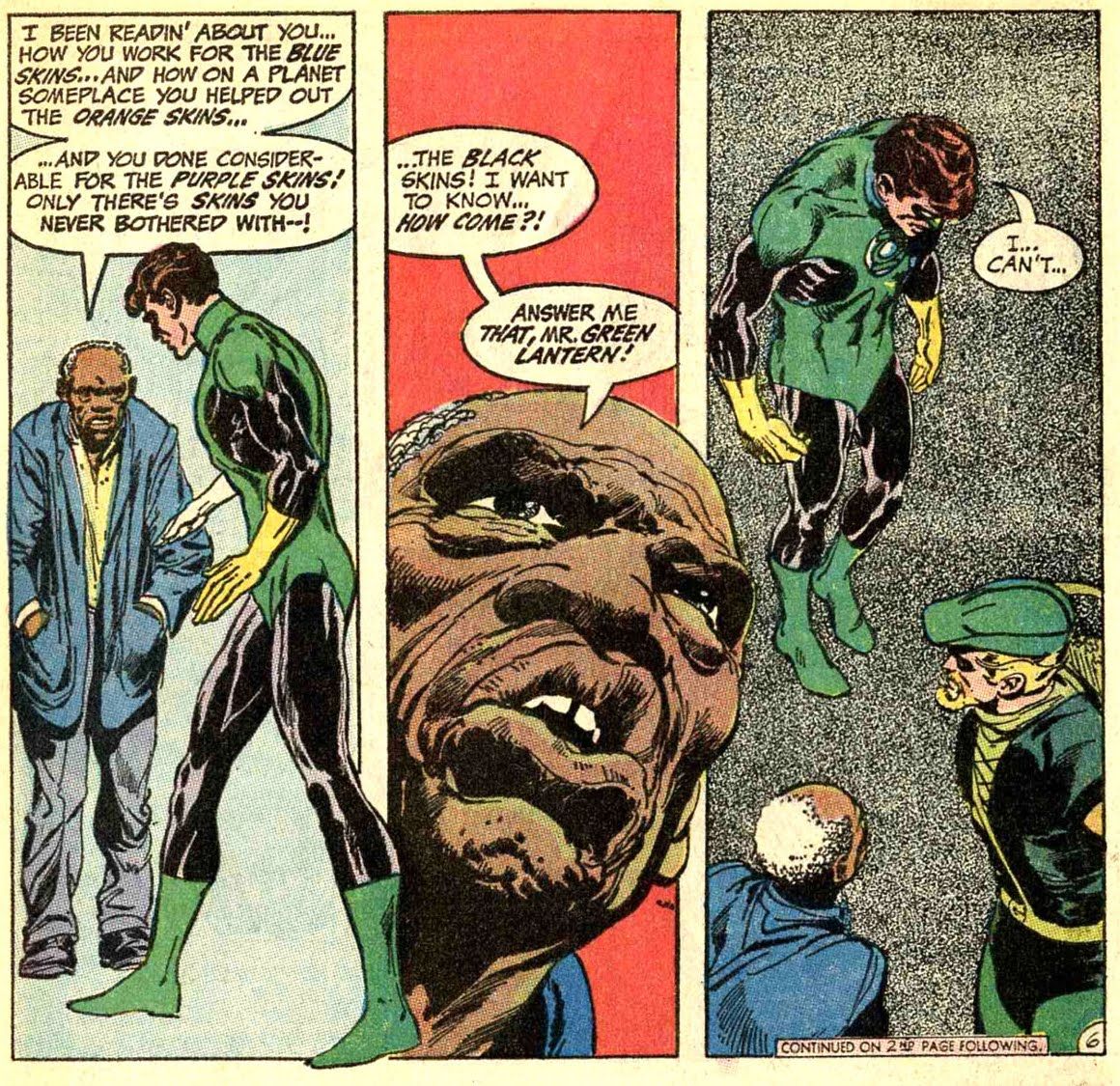

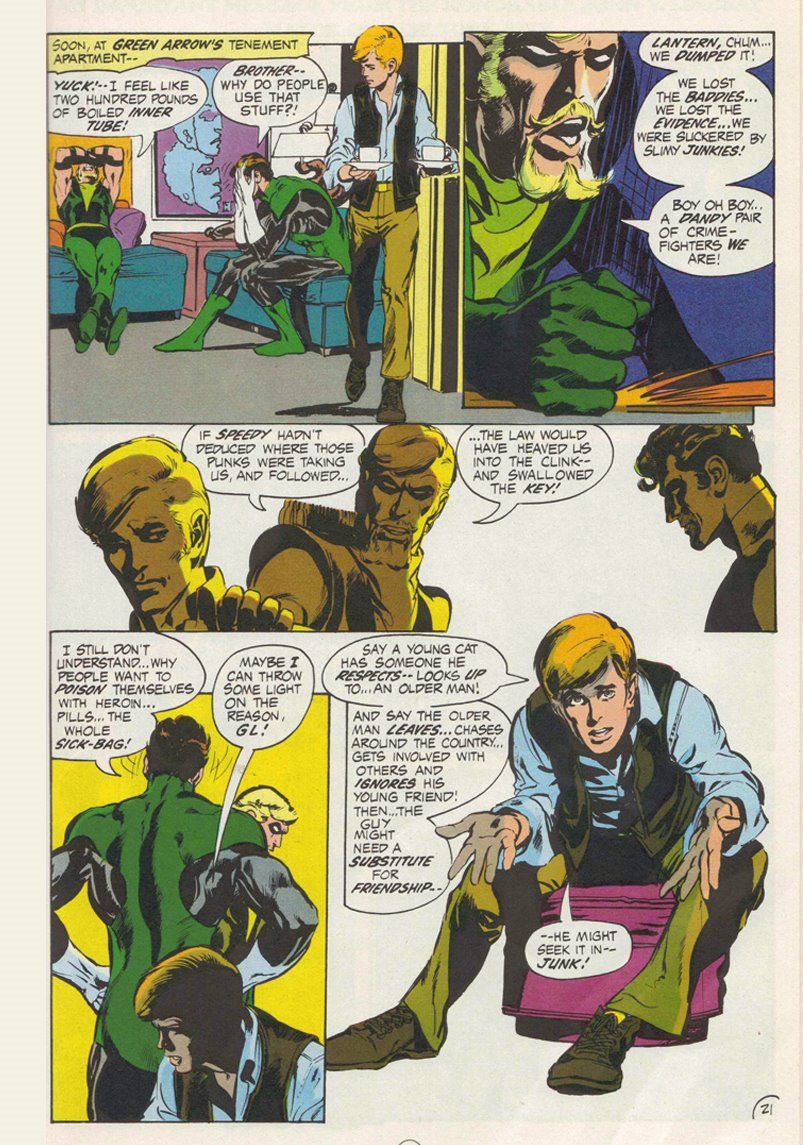

Maybe even longer than that. Really, you can trace it back to the famous O'Neil/Adams run of Green Lantern/Green Arrow.

That run of books launched what comics historians like to call the "relevance" period of the Bronze Age, wherein superheroes sought to deal with real-world issues.

Look, the O'Neil-Adams stuff is rightly regarded as classic and groundbreaking and all of that. But the ugly truth is, it doesn't age well, and if you really look at the stories over the course of the run, the heroes are shown as being more and more clueless and ineffectual.

At the time, no one really noticed because we'd never seen anything like it. But reading the stuff today, the two things that leap out at you are that Green Lantern is a self-obsessed whiner and Green Arrow is a self-obsessed douchebag. They never actually solve any of the real-world problems they encounter-- because they can't. O'Neil was smart enough to know that wouldn't work, even though one of the heroes has a magical wishing ring.

In fact, Denny O'Neil twisted himself into knots trying to get around that part of the Green Lantern premise, and his solution was to make Hal Jordan-- who was, remember, chosen by the ring itself as the most fearless man on the planet-- whiny, hesitant, and full of self-doubt, so that he often couldn't muster the willpower to make his ring work. Or else Hal thought using the ring was cheating. Or the Guardians said he couldn't use it. Always something.

Rereading those stories today, it struck me that the genuinely heroic characters to emerge are Black Canary, who is more interested in helping people than in winning ideological arguments, and Roy Harper, who despite his drug addiction manages to come off as more of a grown-up than his jerk mentor.

Not to go on and on about it. The point is that the genie was out of the bottle. It was now permissible to put superheroes into real-world situations, and writers did so with varying degrees of success. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't.

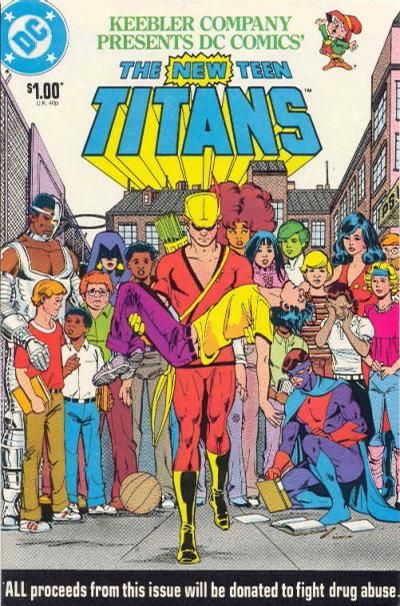

Sometimes it was even at official government request, or because a worthy charity partnered with a major comics publisher to try and get the word out to the Youth of Today about Something Important.

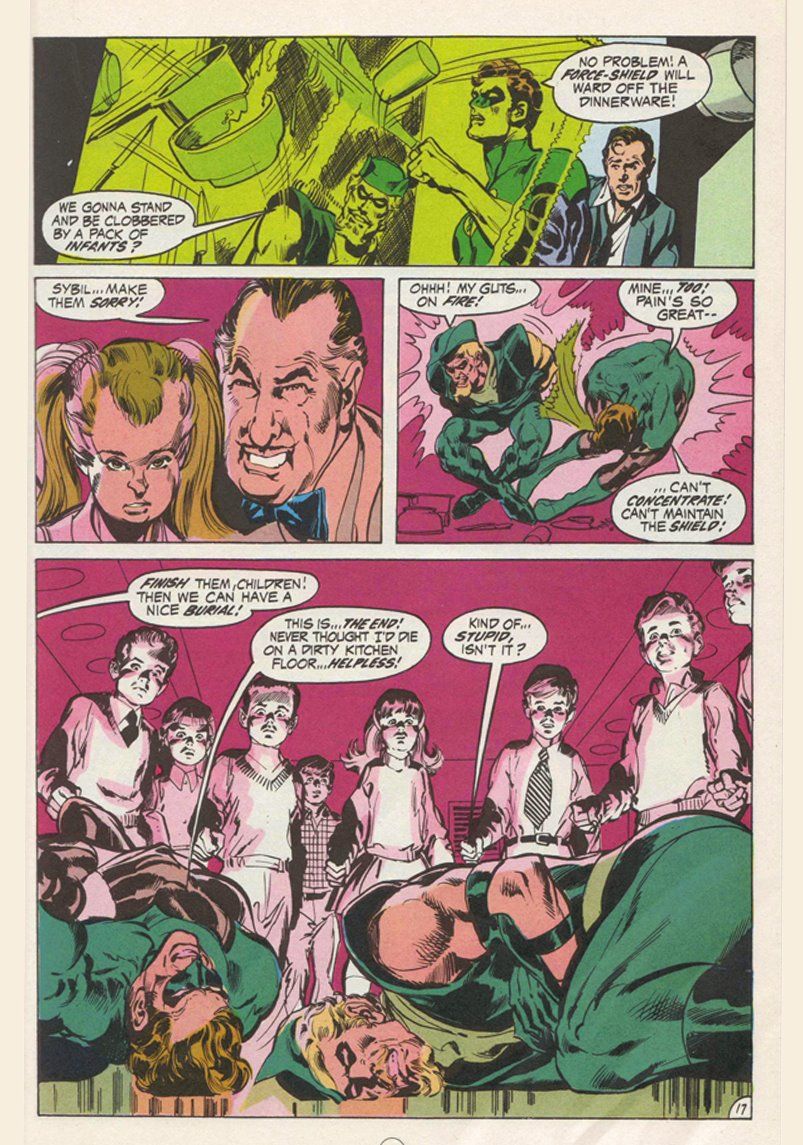

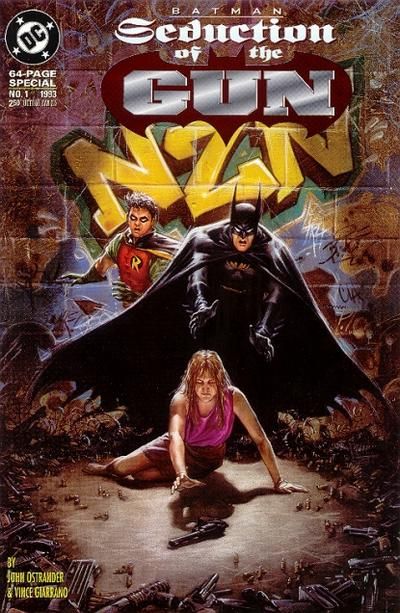

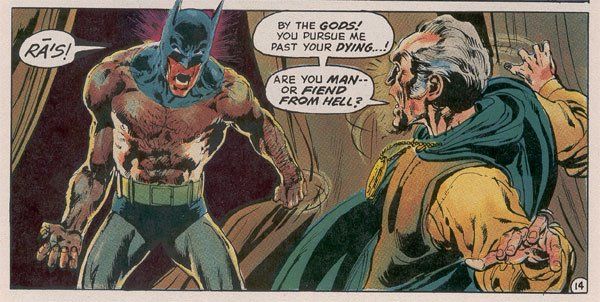

I'm not denigrating the effort and the craft that went into these stories, or suggesting that the creators' intentions weren't pure. But nevertheless, the stories themselves always end up looking faintly ridiculous. Even the ones starring Batman, who's about as close to a 'realistic' superhero as it's possible to get this side of the Punisher.

The bottom line is, no matter how beautifully done the "relevant, real-world" superhero story might be, you still have to sell the reader two ideas-- first of all, that a guy in tights and a cape is believable in that setting, which is very nearly impossible, and secondly, that it's okay to have the story's resolution not actually resolve anything.

It's the second one that's the killer. Readers know that Batman isn't really going to solve the problem of the Bangkok child-sex trade or of Asian peasant kids getting blown up by land mines. We know this. No matter how skillfully the writers of these stories come at it, we know that by the end of the story, Batman (or the Teen Titans, or Spider-Man, or whoever) is going to be standing there saying something like, "I hope humanity realizes the horror of this [insert real-world problem here-- drugs, gangs, etc.]... people need to wake up before it's too late!" I see that and invariably, my subconscious adds, "... but me, I'm going to go kick the crap out of some guy in a silly outfit robbing a bank. THAT, I can deal with. This is too hard."

Whether it's something as hamfisted as Spider-Man recounting where the bad man touched him or something harrowing like Andrew Vachss' Batman story about child prostitution, the end result is the same -- a vague aura of embarrassment over having a superhero in that situation.

I can think of one time that this superheroes-in-the-real-world idea actually worked. Where I believed it absolutely. Alan Moore's Watchmen.

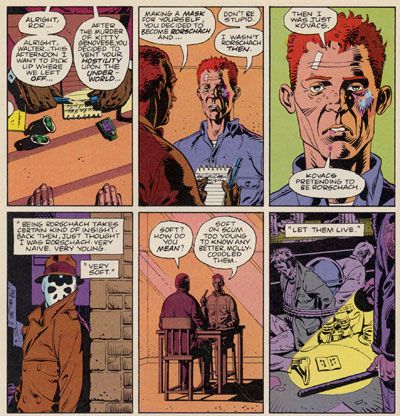

...but here's the thing. Alan Moore made the conceit of superheroes believable by subverting it. He ruthlessly extrapolated out all the different costumed-hero personality types we've grown used to over the years -- the masked avenger of the streets, the hero beloved by the people, the tough government soldier, the hot babe in the skimpy outfit-- and deconstructed them to the point that it was actually uncomfortable to read about them. Moore makes the point, over and over, that if you are putting on a mask and costume to fight crime then there's probably something wrong with you. And he doubled down on it by positing that if there really were people with super powers out there, they would immediately be seized upon by government for political purposes and generally just deform the shape of human history.

It's often brilliant and remarkably thorough in its extrapolations. But it's not very much fun. It's hard for us long-time readers of superhero comics to get our heads around that aspect of Watchmen -- that superheroes, if they really existed, would be kind of creepy, and maybe a little pathetic.

It's interesting to note that when the comics were first coming out, Alan Moore said in interviews that he expected readers to latch on to Nite Owl.That he thought that would be the breakout character because Nite Owl is the least disturbing.

Instead, it was Rorschach. Who in many ways is the most disturbing character. Certainly, Moore intended Rorschach to be the most disturbed.

Why? Because he's a badass. Rorschach may be smelly and deranged and living off garbage, but he's still tough and scary and cool. He has most of the best lines in the book. "He's hardcore," is the expression I often see comics fans use when talking about him.

And that's what we want in a superhero story. Not "realism."

Dave Campbell, of the late and lamented

Dave's Long Box, has a wonderful term for this phenomenon. He calls it the

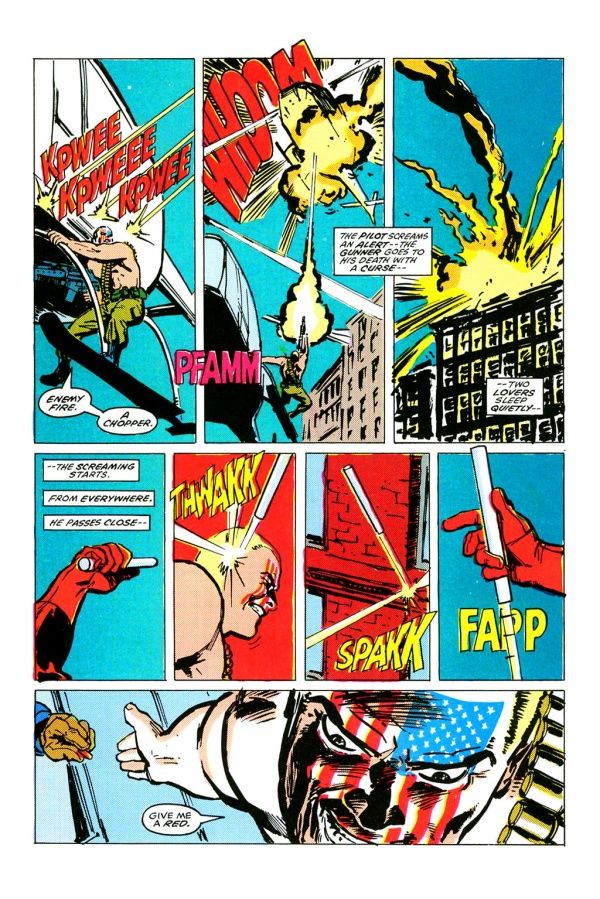

"Fuck Yeah!" moment.

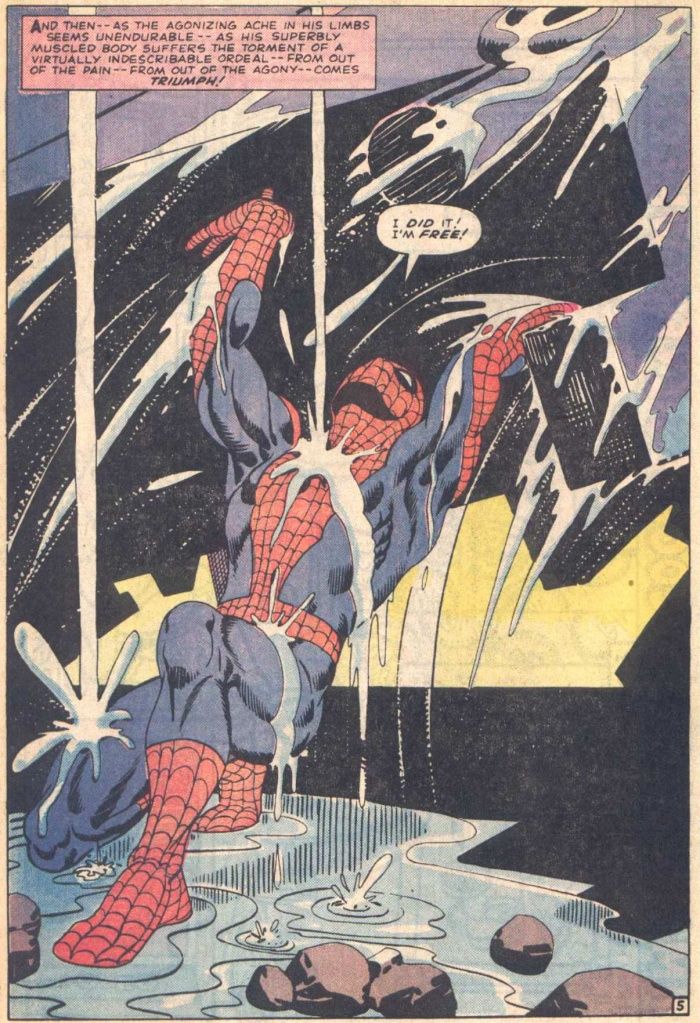

We all know what a "Fuck Yeah!" moment looks like. It's that shining moment in a story when everything you like about a particular character crystallizes, where it's all right there and you realize Oh, yeah, there it is. You go.

Like in The Warriors, when Ajax whirls to face the leader of the Baseball Furies and snarls, "I'm gonna shove that bat up your ass and turn you into a Popsicle."

If you've seen the movie, you remember that up until that point Ajax is really kind of an asshole. He's not terribly bright. He is surly and rebellious and possibly even an admitted rapist. But in that moment, all that falls away. We love him and we are rooting for him to clean the Baseball Fury's clock. That's the power of the Fuck Yeah! moment.

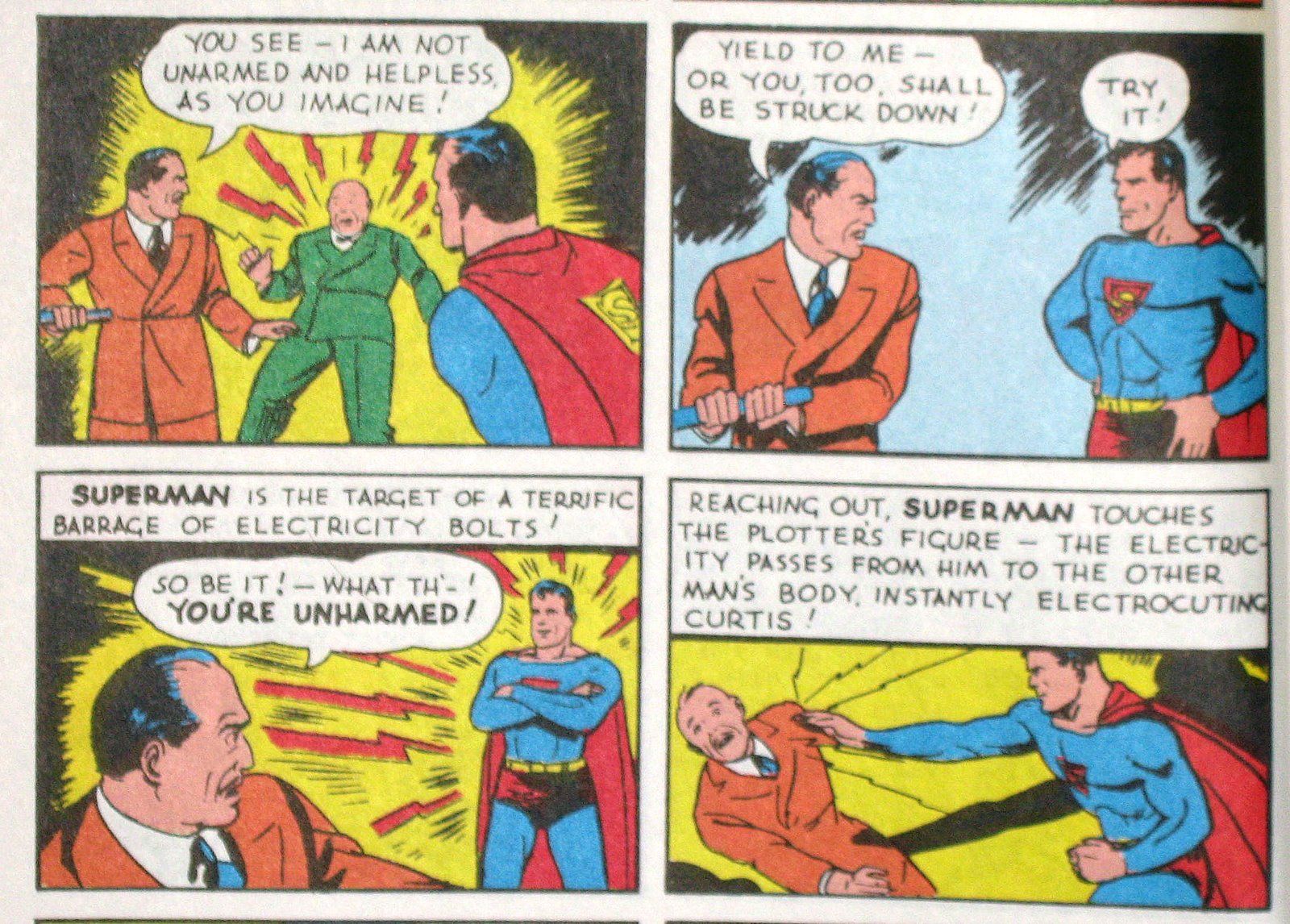

Superhero stories, as I've explained above, are terrible at realism. But they excel at the Fuck Yeah! moment.

In fact, you could say that it's what they're designed to provide. You pick up a book about a super-strong guy who can fly, you're not there to see him address racism or industrial pollution. You want to see him throw a few cars around and see some damn bullets bounce off his chest.

The great superhero comic moments, the ones we remember most fondly, aren't realistic at all.

But I'm willing to bet, if you are honest with yourself about it, that every last one of them is a "Fuck Yeah" moment of some kind.

Certainly, mine are. Hell, that was what got me interested in superheroes in the first place, long ago. In 1966, when I saw Batman and Robin leap into the Batmobile, and Robin says, "Atomic batteries to power! Turbines to speed!" and Batman coolly responds, "Roger, ready to move out," and they go roaring out of the Batcave-- I'm telling you, that was a total Fuck Yeah! moment for six-year-old me.

Might have been the very first one. (It was either that or Space Ghost bearing down on Metallus or Brak or someone, yelling "Time to use my HEAT FORCE!")

That exhilaration, that moment when you lean forward and something in the back of your head says, oh, it's ON! ...that's what I fell in love with. That's when I dived into the superhero fantasy and never looked back.

I think that's true for most of us. And I think that even those creators who made their rep doing "realistic, grim-n-gritty" superhero stories know that too much realism is going to sabotage the whole enterprise.

Look, I've said this before, but when fans talk about wanting more "realism" in their superhero stories, I don't think that's what they mean. I think they want verisimilitude. Which is a ten-dollar word that translates to, more or less, "fake realism that I can sort of believe in even though I know it's silly."

We don't want actual realism in our superhero fiction. That brings all the uncomfortable truths that Alan Moore gave us in Watchmen. We just want enough nods to real life that we can get swept up in the fantasy without feeling like we need to apologize or make allowances.

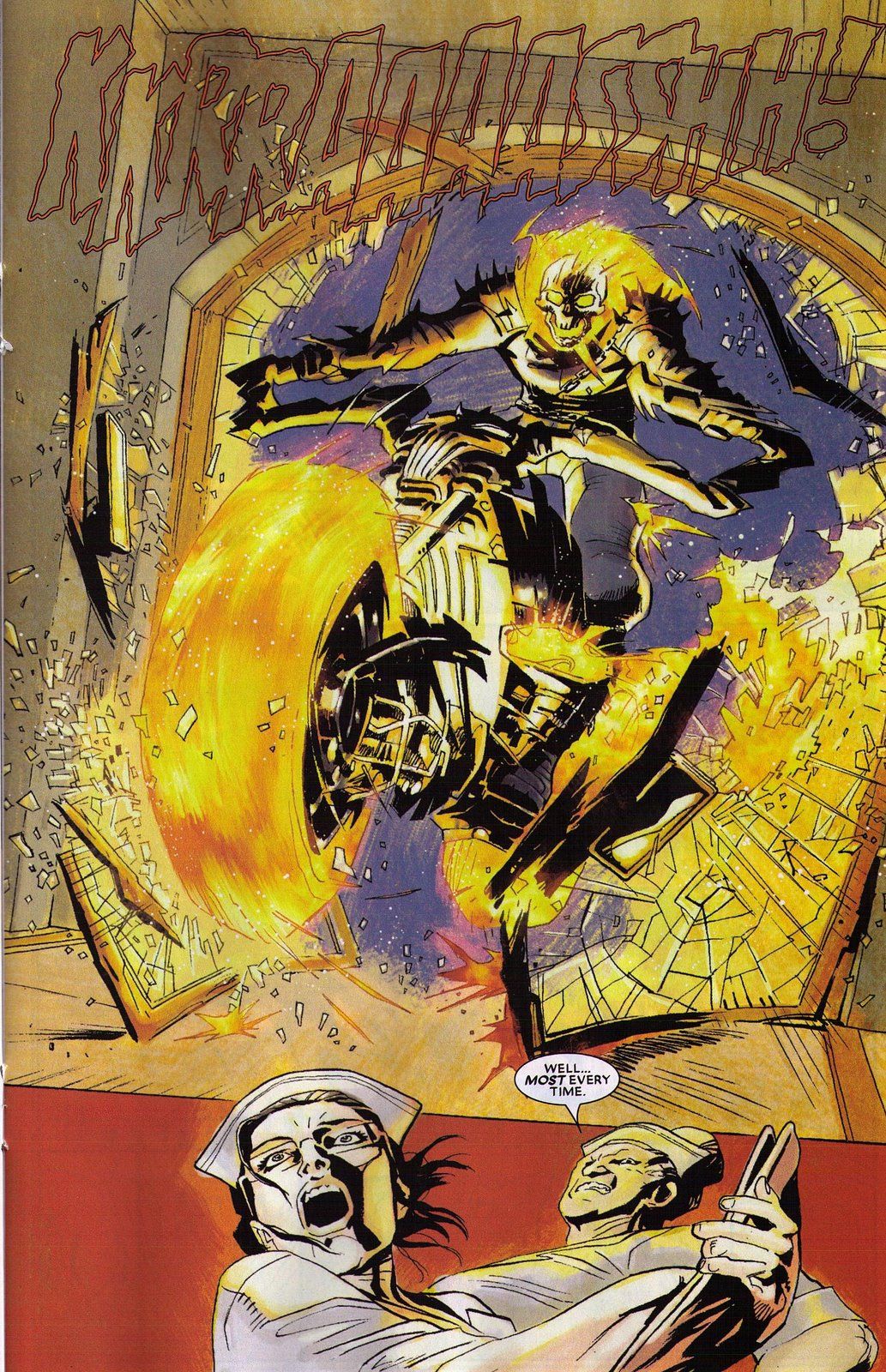

The reason this all came to mind this week is because, the same day I read about Greg Burgas being annoyed with Superman trying to address real-world concerns of industrial pollution and organized labor, the Ghost Rider omnibus with all those great Jason Aaron stories arrived.

Reading it, with Greg's comments about Superman still swirling around in the back of my head, I realized something.

No matter what your superhero story might be, if it doesn't deliver a fuck yeah! in there somewhere, I'm probably not going to hang in there with it.

I have lots of books around here that offer realistic fiction. But for pure fist-pumping adrenaline-fueled adventure, there's really nothing to beat superheroes.

Understand, I'm not advocating a return to the simple-minded superheroics of the Golden Age or anything like that. Sure, you can tell superhero stories about adult concerns. Sure, there are all kinds of ways to talk about real-life problems using superhero characters as metaphor and all of that stuff. I'm not discounting that.

I'm just saying that, if you're writing a superhero story and you leave out the fuck yeah!.... well, then, what's the point of doing it as a superhero story at all? Because that moment is what superhero comics literally were built around.

Even Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams knew that, back in the day.

See you next week.