In "Saga" #23 by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples, Marko and Alana's marriage is on the rocks in the aftermath of a serious fight, and both Dengo and Prince Robot IV get closer to their goals and quarries.

One of the markers of Vaughan's subtlety as a writer is how gradually and how far Marko and Alana, arguably the central protagonists, have changed or enlarged in complexity since the debut issue. In the latest story arc, the constant exile, living in hiding and being on the run has taken their toll, and both characters behave in ugly ways in their half-acknowledged misery and dysfunction. Alana is in denial about drug addiction and self-righteous when she's angry or scared. Marko has been dangerously close to infidelity for a while. The shift has been gradual, and the two still recognizable as themselves, but they're far more messed up and unlikable than when they and the readers were in the flush of a honeymoon period.

"Saga" #23 isn't all gloomy. The interjection of Hazel's insistence on having her "Ponk Konk" is pivotal to the action, but is also poignant and funny. Through Hazel's retrospective voiceover, Vaughan creates further suspense about Alana and Marko's fate as a couple, not the what or why, but the when and how. The investment in the story is even higher as the scales tip towards tragedy, and the convergence of characters upon Marko's return at the end is painfully intense, in a good way. Izabel's lecture is the only part that feels artificial in any way, only because it's a little too convenient for the plot to have a friend give Alana some tough love at the exact right moment.

The villains get the same care as Marko and Alana, with the effects moving in the opposite direction. Prince Robot's grief for his dead wife and worry over his son make him more sympathetic as tries to track down his kidnapped child. Yuma's cowardice and drug-dealing ways are lightened by her relief, shame and surprising self-awareness in the final scene of "Saga" #23. Last but not least, Dengo's casual violence is shocking and sickening, but he comes across as vulnerable, too. He's lost his son. He's poor, disenfranchised, desperate and probably mentally ill. He's a terrorist, but a realistic one. Dengo's just an angry, ordinary man who has done terrible things because he's named his oppressors, but then made them a scapegoat for everything wrong, and because he's turned to bloodshed as an answer.

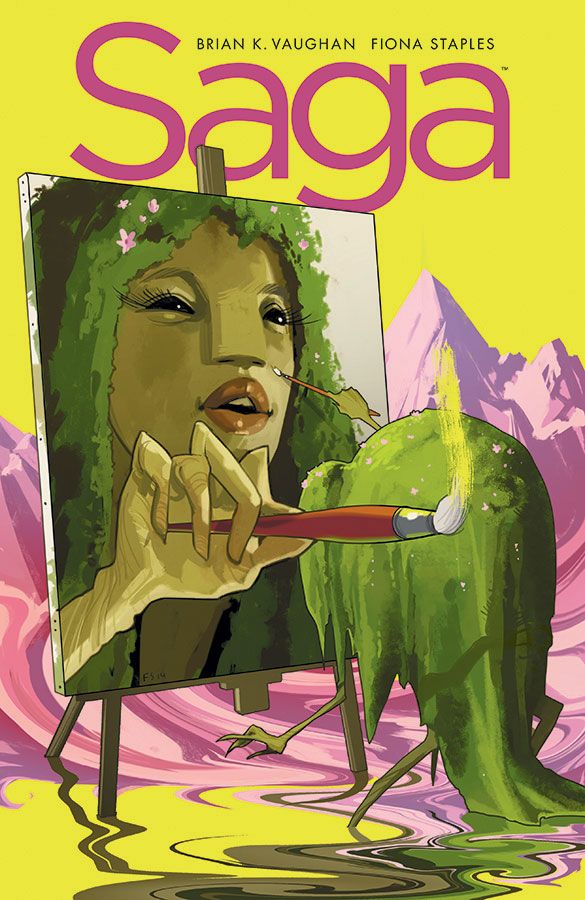

Vaughan's dialogue is strengthened by Staples' superb body language. Prince Robot IV and Dengo don't have faces or facial expressions in the way that readers are used to, so Staples has to make their body language count for that much more, and she does. Dengo's erratic fragility and Prince Robot IV's more controlled, and scarier, instability and rage come through in the way Staples makes them move within the panel and the page.

Staples' panel compositions also work beautifully with the action, and in the fight scenes, the shape of the panels slant and tilt into each other to mimic the visual disorientation and accelerated pace of battle. Staples' draughtsmanship is superb and her foreshortening and anatomy always look right, and she's always taking risks. For "Saga" #23, her coloring choices are gloomier than usual with lots of muddy shadows and nighttime blues and reinforce the tense, sad atmosphere of the events.

Vaughan and Staples have taken their characters to a dark place in a psychologically realistic way -- what has happened to Alana and Marko, or even to Dengo or Yuma, are things that happen to ordinary people all the time. The drama is universal, but the pain feels fresh, and this naturalism strengthens the breadth of "Saga" by dwelling on the ways that people can come together and fall apart, both in their relationships and in their own souls.